The Shift in Women's Rights During the Augustan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Euphiletos' House: Lysias I Author(S): Gareth Morgan Source: Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-2014), Vol

Euphiletos' House: Lysias I Author(s): Gareth Morgan Source: Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-2014), Vol. 112 (1982), pp. 115-123 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/284074 Accessed: 13-09-2018 13:27 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/284074?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-2014) This content downloaded from 69.120.182.218 on Thu, 13 Sep 2018 13:27:29 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Transactions of the American Philological Association 112 (1982) 115-123 EUPHILETOS' HOUSE: LYSIAS I GARETH MORGAN University of Texas at Austin Lysias I, On the killing of Eratosthenes, is often cited in discussions of Greek domestic architecture for the details incidentally given about the house of the defendant, Euphiletos. This paper attempts to define rather more closely than before what we know about Euphiletos' house, and to relate it to archaeological evidence on Athenian private dwellings.' We may examine the relevant passages in the order they are presented by Euphiletos: (1) fHproV .ErV O VV, w aV8pES, . -

Coriolanus and Fortuna Muliebris Roger D. Woodard

Coriolanus and Fortuna Muliebris Roger D. Woodard Know, Rome, that all alone Marcius did fight Within Corioli gates: where he hath won, With fame, a name to Caius Marcius; these In honour follows Coriolanus. William Shakespeare, Coriolanus Act 2 1. Introduction In recent work, I have argued for a primitive Indo-European mythic tradition of what I have called the dysfunctional warrior – a warrior who, subsequent to combat, is rendered unable to function in the role of protector within his own society.1 The warrior’s dysfunctionality takes two forms: either he is unable after combat to relinquish his warrior rage and turns that rage against his own people; or the warrior isolates himself from society, removing himself to some distant place. In some descendent instantiations of the tradition the warrior shows both responses. The myth is characterized by a structural matrix which consists of the following six elements: (1) initial presentation of the crisis of the warrior; (2) movement across space to a distant locale; (3) confrontation between the warrior and an erotic feminine, typically a body of women who display themselves lewdly or offer themselves sexually to the warrior (figures of fecundity); (4) clairvoyant feminine who facilitates or mediates in this confrontation; (5) application of waters to the warrior; and (6) consequent establishment of societal order coupled often with an inaugural event. These structural features survive intact in most of the attested forms of the tradition, across the Indo-European cultures that provide us with the evidence, though with some structural adjustment at times. I have proposed that the surviving myths reflect a ritual structure of Proto-Indo-European date and that descendent ritual practices can also be identified. -

Giovanni De Matociis and the Codex Oratorianus of the De Uiris Illustribus Urbis Romae’, Exemplaria Classica: Journal of Classical Philology 24 (2017), Pp

1 [This is the peer-reviewed version of the following article: J.A. Stover, G. Woudhuysen, ‘Giovanni de Matociis and the Codex Oratorianus of the De uiris illustribus urbis Romae’, Exemplaria Classica: Journal of Classical Philology 24 (2017), pp. 125-148, I.S.S.N.: 2173-6839, which has been published in its final form at http://www.uhu.es/publicaciones/ojs/index.php/exemplaria/article/view/3211] Giovanni de Matociis and the Codex Oratorianus of the De uiris illustribus urbis Romae ABSTRACT: One of the most curious manuscripts of the De uiris illustribus is Biblioteca dei Girolamini, XL pil. VI, no. XIII. This manuscript has been thought either to go back to the early Veronese humanist Giovanni de Matociis, or to contain authentic ancient information. We demonstrate that the manuscript has nothing to do with Matoci, but is closely linked to Giacomo Filippo Foresti, a late-fifteenth-century historian. Its chief feature of interest is that it shares some readings with another branch of the tradition of the DVI, the Corpus Aurelianum, thus providing new evidence for the circulation of that text. RESUMEN: Uno de los manuscritos del De uiris illustribus (DVI) más curiosos es Nápoles, Biblioteca dei Girolamini, XL pil. VI, no. XIII. Entre los rasgos que se han asociado a este manuscrito se encuentran dos: que se remonta al temprano humanista veronés, Giovanni de Matociis, y que contiene información antigua auténtica. Demostramos que el manuscrito no tiene nada que ver con Matoci, sino que está estrechamente ligado a Giacomo Filippo Foresti, un historiador del fines del siglo XV. -

A Corpus-Based Comparative Analysis of in the Line of Fire and Sab Se Pehle Pakistan

Translation as Accommodation: A Corpus-based Comparative Analysis of In the Line of Fire and Sab Se Pehle Pakistan By Aamir Majeed M Phil (Linguistics) B. Z. U. Multan, 2009 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In English (Linguistics) To FACULTY OF LANGUAGES NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MODERN LANGUAGES, ISLAMABAD Aamir Majeed, 2015 ii NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MODERN LANGUAGES FACULTY OF LANGUAGES THESIS AND DEFENSE APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have read the following thesis, examined the defense, are satisfied with the overall exam performance, and recommend the thesis to the Faculty of Languages for acceptance. Thesis Title: Translation as Accommodation: A Corpus-based Comparative Analysis of In the Line of Fire and Sab Se Pehle Pakistan Submitted By: Aamir Majeed Registration # 373-PhD/Ling/Jan 10 Doctor of Philosophy Name of Degree English Linguistics Name of Discipline Dr. Fauzia Janjua _________________________ Signature of Research Supervisor Name of Research Supervisor Prof. Dr. Muhammad Safeer Awan ____________________ Name of Dean FoL Signature of Dean FoL Maj. Gen. Zia Uddin Najam HI(M) (Retd) ___________________ Name of Rector Signature of Rector __________________________ (Date) iii CANDIDATE’S DECLARATION I, Aamir Majeed Son of Abdul Majeed Registration # 373-PhD/Ling/Jan 10 Discipline English (Linguistics) Candidate of Doctor of Philosophy at the National University ofModern Languages do hereby declare that the thesis Translation as Accommodation: A Corpus-based Comparative Analysis of In the Line of Fire and Sab Se Pehle Pakistan submitted by me in partial fulfillment of PhD degree, is my original work, and has not been submitted or published earlier. -

Clarissimi Viri Joshua Roberts

Clarissimi Viri Joshua Roberts Livy’s histories of Horatius Cocles and Gnaeus Marcius Coriolanus The University of Georgia Department of Classics Summer Institute June, 2015 Forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit. 1 Tibi, Domine, qui me potentem facit. Maximas gratias fidelissimae uxori carissimisque liberis, qui semper efficiunt me laetum domum redire. Thank you to my Latin teachers: Mrs. Counts, Mr. Spearman, and Ms. Brown for introducing me to Latin. Mr. Philip W. Rohleder, who was the very embodiment of what my career has become. Uncle Phil, I cannot thank you enough for your friendship and your excellent example. I am still trying to be like you. Dr. Evelyn Tharpe, Dr. Ron Bohrer, and Dr. Josh Davies at the University of Tenneessee at Chattanooga. Dr. Bohrer, you showed me how to be merciful as a teacher. My professors in the University of Georgia Summer Institute faculty: Dr. Christine Albright, Dr. Naomi Norman, Dr. Robert Harris, Dr. John Nicholson, and Dr. Charles Platter. I am a better teacher because of you. Special thanks to Dr. Platter and Dr. Nicholson for serving as the committee for my final teaching project. JLSR MMXV 2 Contents Care Lector, .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Livy’s Preface to Ab urbe condita ................................................................................................................ 8 Horatius at the Bridge, II.10 ...................................................................................................................... -

5. Hogg, Emotion and Greekness

Histos Supplement ( ) – EMOTION AND GREEKNESS IN DIONYSIUS OF HALICARNASSUS’ ACCOUNT OF THE EXILE OF CORIOLANUS * Dan Hogg Abstract : Dionysius’ account of Coriolanus’ exile is rarely treated on its own terms, normally being deprecated as inferior to Livy or Plutarch’s version of the same. On the contrary, Dionysius’ account is a powerful illustration of his method in combining Roman source-material with Greek literary heritage. In particular, Dionysius uses epic and technical elements of stage language to draw out the psychological tensions at play in the story. This account, therefore, not only helps us get closer to Dionysius’ vision of Romanness, as Greek-inflected and distinct from Livy’s; it also problematises tough, Roman masculinity, suggesting that Dionysius is a more subtle observer of Rome than is usually imagined. Keywords: Coriolanus, family, mother, Livy, tragic history, Dionysius of Halicarnassus his paper considers Dionysius’ narration of Coriolanus’ encounter with his mother ( .@–), Twith especial regard to Dionysius’ presentation of their emotional relationship, and the ways in which this * I would like to thank all those who commented on versions at various stages, starting with Chris Pelling, who supervised the DPhil of which a version of this formed a part; Katherine Clarke and Stephen Oakley, who examined the DPhil; Julietta Steinhauer; the audience in Lampeter; the editors and anonymous reviewer of Histos ; and Alexander Meeus, for organising the conference where this was presented, and then performing his role as editor so generously. All references to Dionysius are to the Antiquitates Romanae , unless otherwise noted. Dan Hogg relationship drives the plot of Dionysius’ story. -

DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE AS RHETORICAL DEVICE: the GYNAECONITIS in GREEK and ROMAN THOUGHT KELLY I. MCARDLE a Thesis Submitted to T

DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE AS RHETORICAL DEVICE: THE GYNAECONITIS IN GREEK AND ROMAN THOUGHT KELLY I. MCARDLE A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Classics in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Hérica Valladares Alexander Duncan James O’Hara © 2018 Kelly I. McArdle ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kelly I. McArdle: Domestic architecture as rhetorical device: The gynaeconitis in Greek and Roman thought (Under the direction of Hérica Valladares) In this thesis, I explore the gap between persistent literary reference to the gynaeconitis, or “women’s quarters,” and its elusive presence in the archaeological record, seeking to understand why it survived as a conceptual space in Roman literature several centuries after it supposedly existed as a physical space in fifth and fourth-century Greek homes. I begin my study by considering the origins of the gynaeconitis as a literary motif and contemplating what classical Greek texts reveal about this space. Reflecting on this information in light of the remains of Greek homes, I then look to Roman primary source material to consider why the gynaeconitis took up a strong presence in Roman thought. I argue that Roman writers, although far-removed from fifth and fourth-century Greek homes, found the gynaeconitis most useful as a mutable and efficient symbol of male control and a conceptual locus of identity formation. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS -

Small Business, Entrepreneurship, and Franchises

Small Business, Entrepreneurship, and Franchises 5 Learning Objectives ©iStockphoto.com/mangostock What you will be able to do once you complete this chapter: 1 Define what a small business is and recognize 4 Judge the advantages and disadvantages of the fields in which small businesses are operating a small business. concentrated. 5 Explain how the Small Business Administration 2 Identify the people who start small businesses helps small businesses. and the reasons why some succeed and many fail. 6 Appraise the concept and types of franchising. 3 Assess the contributions of small businesses to our economy. 7 Analyze the growth of franchising and franchising’s advantages and disadvantages. Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 7808X_05_ch05_p135-164.indd 135 30/10/10 8:29 PM FYI inside business Did You Franchising Feeds Growth of Five Guys Burgers and Fries Know? Five Guys Burgers and Fries has a simple recipe for success in the hotly competitive casual restau- rant industry: Serve up popularly priced, generously sized meals in a family-friendly atmosphere. Today, Five Guys Founders Jerry and Janie Murrell opened their first burger place in 1986 near Arlington, Virginia. Naming the growing chain for their five sons, the husband-and-wife team eventually opened four Burgers and Fries more restaurants in Virginia. -

Preserving the Archaeological Past in Turkey and Greece the J.M

Preserving the Archaeological Past in Turkey and Greece THE J.M. KAPLAN FUND GRANTMAKING INITIATIVE, 2007-2015 PRESERVING THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL PAST IN TURKEY AND GREECE The J.M. Kaplan Fund Grantmaking Initiative, 2007 –2015 2 THE J.M. KAPLAN FUND www.jmkfund.org Published by The J.M. Kaplan Fund 71 West 23rd Street, 9th Floor New York, NY 10010 Preserving the Archaeological Past in Turkey and Greece publication copyright © 2017 The J.M. Kaplan Fund. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher. Publication design by BRADY ART www.bradyart.com Cover: Anastylosis of the Propylon at Aphrodisias, Turkey Right: Temple of Artemis at Sardis, Turkey 3 4 CONTENTS 6 FOREWORD By Ken Lustbader 8 INTRODUCTION 12 GRANTMAKING MAP SITE PRESERVATION GRANTS NEOLITHIC PERIOD 14 Göbekli Tepe 20 Çatalhöyük BRONZE AGE PERIOD 24 Mochlos & Ayios Vasileios 30 Pylos 32 Tell Atchana & Tell Tayinat IRON AGE PERIOD 36 Kınık Höyük 38 Gordion ARCHAIC-CLASSICAL PERIOD 42 Labraunda HELLENISTIC PERIOD 46 Delos ROMAN PERIOD 50 Aphrodisias 56 Ephesus BYZANTINE PERIOD 60 Hierapolis 64 Kızıl Kilise (Red Church), Cappadocia 66 Meryem Ana Kilise (Mother of God Church), Cappadocia 68 Ani 5 MULTI-PERIOD SITES 72 Pergamon 76 Sardis 80 Karkemish CAPACITY BUILDING GRANTS 82 REGRANTING PROGRAM Institute for Aegean Prehistory Study Center for East Crete 83 CONFERENCES, SEMINARS, & WORKSHOPS Koç University Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations Istanbul Kultur University German Archaeological Institute at -

Catalogue ... Annual Exhibition / Chicago Architectural Sketch Club

I1eyenberg__ F_ir_e __ P_ro_o_fi_n~g_C_o_. Meyenberg Patent Fire Proofing Floor Arches, Part/· tions, Furring, Boller Covers, Column Covers, and other Fire Proof Tile work for Building 1\0TE- Our Tlllnr l• 50 Pfr crntll,ht~r. double I be ~trcnrtb. and chcaptr, then all other ma ..facturu. TELEPHONE MAIN 3035 Main Office, 705, 167 Dearborn St. CHICAGO Th~ followlnJC a re som~ of the buildings erected the past e ig hteen m onths In "hlch the Me) en b erg Fire Proof Partitions, F lour Arches and muterhtls generally have been used : Th~Count)' l..'uurt ""'"~ """""""h Ill. Hubiu~cr Offic~ llull<liu~. '>c\\ llnvcn. Conn. Henry Sl11re" ond Ap.lrl. llldl( R<K'kfunl, Ill Schuulon lluildinJ:', J.;.,,l;uk, luw 1. lligh :-iehool Ruil<linjl, ' lonticelln. lnd " C"' Elysium Thentr<· \lemphi" Tcnu ~wnncll AIIRrlln;,nt 1111111 Knnk~k~t'. Ill. \')·hun fur th~ llllnd, j.ul~•villt: WI• l>u Pn11e Co. l:unrl "'"''"· \l'lll·uton 111 W<><><l•lrom Apnnwclll lluildlnl{ Chica)lu. l'irst!St'\\'Cumh.. rlnutl t'n' Ch >tch Chicngo \\'allers ludn•trinllluihliu~:.Chlc.-ngo. l'rntt Slor" lluitdlnA: Chlca)ln. lh>marck Sehoul lluiltlln_l(. Chic•!C"· 'I'he Furr.,stvillc, Chi<'.IIIU tlope A\·euuc SChool llutldllllt, ChtCBI(O. (;r~"" S<:hnnl Bu•ltlin.~t. Chinii(U. :>;<'w Newb<'rn· ,.,.,ho<1l lluitclin~t, Chica);'O. fluncan ..,choot llnil<ling. l'hk;t!C >. .\rmil:t.~tc St·hoollluitrlin!(. Chk:t!l:o. l.ea,·ill Schroul lluildin~t. ChiruA:•>. I kat~∙ N:huol Uulldiu)t. l'hiettl(u. Wntlnc~ Schoollluitdiuor. Chi<-1~ >. -

Domestic Architecture in the Greek Colonies of the Black Sea from the Archaic Period Until the Late Hellenictic Years Master’S Dissertation

DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE IN THE GREEK COLONIES OF THE BLACK SEA FROM THE ARCHAIC PERIOD UNTIL THE LATE HELLENICTIC YEARS MASTER’S DISSERTATION STUDENT: KALLIOPI KALOSTANOU ID: 2201140014 SUPERVISOR: PROF. MANOLIS MANOLEDAKIS THESSALONIKI 2015 INTERNATIONAL HELLENIC UNIVERSITY MASTER’S DISSERTATION: DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE IN THE GREEK COLONIES OF THE BLACK SEA FROM THE ARCHAIC PERIOD UNTIL THE LATE HELLENISTIC YEARS KALLIOPI KALOSTANOU THESSALONIKI 2015 [1] CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 4 ARCHAIC PERIOD 1.1. EARLY (610-575 BC) & MIDDLE ARCHAIC PERIOD (575-530 BC): ARCHITECTURE OF DUGOUTS AND SEMI DUGOUTS .................................................................................... 8 1.1. 1. DUGOUTS AND SEMI-DUGOUTS: DWELLINGS OR BASEMENTS? .................... 20 1.1. 2. DUGOUTS: LOCAL OR GREEK IVENTIONS? ........................................................... 23 1.1. 3. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................. 25 1.2. LATE ARCHAIC PERIOD (530-490/80 BC): ABOVE-GROUND HOUSES .................. 27 1.2.1 DEVELOPMENT OF THE ABOVE-GROUND HOUSES .............................................. 30 1.2.2. CONCLUSION: ............................................................................................................. 38 CLASSICAL PERIOD 2.1. EARLY CLASSICAL PERIOD (490/80-450 BC): ............................................................ 43 -

Diapositive 1

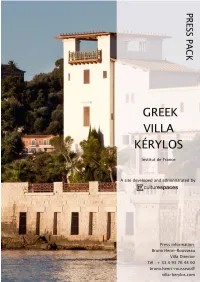

1 Page 3 Culturespaces, representative for the Greek Villa Kérylos Page 4 Institut de France, owner of the Greek Villa Kérylos Page 5 Two designers with one passion Page 7 A palace inspired from Ancient Greece Page 11 The villa’s unique collections Page 12 Events in 2015 Page 13 The action of Culturespaces at the Villa Kérylos Page 16 The Culturespaces Foundation Page 17 Practical information 2 Culturespaces, representative for the Villa Grecque Kérylos “Our aim is to help public institutions present their heritage and develop their reputation in cultural circles and among tourists. We also aim to make access to culture more democratic and help our children discover our history and our civilisation in remarkable cultural sites” Bruno Monnier, CEO and Founder of Culturespaces. With 20 years of experience and more than 2 million visitors every year, Culturespaces is the leading private organisation managing French monuments and museums, and one of the leading European players in cultural tourism. Culturespaces produces and manages, with an ethical and professional approach, monuments, museums and prestigious historic sites entrusted to it by public bodies and local authorities. Are managed by Culturespaces: • Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris (since 1996) • Villa Ephrussi de Rothschild, Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat (since 1992) • Greek Villa Kerylos, Beaulieu-sur-Mer (since 2001) • Carrières de Lumières , Baux-de-Provence (since 2012) • Château des Baux de Provence (since 1993) • Roman Theatre and Art and History Museum of Orange (since 2002) • Nîmes Amphitheatre, the Square House, the Magne Tower (since 2006) • Cité de l’Automobile, Mulhouse (since 1999) • Cité du Train, Mulhouse (since 2005) • And in May 2015, Culturespaces launches in Aix-en-Provence a new Art Centre in a gem of the XVIIIth century: Caumont Art Centre, in a mansion, belonging to Culturespaces.