Acta Rerum 16.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dissertation Outline

COMMON AND DIFFERING IMPACTS OF THE EUROPEAN FRAMEWORK FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES WITH SPECIAL CONSIDERATION OF SWEDEN AND POLAND A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Katarzyna M. Polanska IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advisers: Professor Ann Hironaka and Professor Joachim J. Savelsberg December 2012 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I want to thank my advisors, Ann Hironaka and Joachim Savelsberg. Ann’s excellent guidance, caring, patience, and encouragement truly kept me going. She was always available to discuss my ideas, and provide feedback and suggestions on how to strengthen my arguments. Joachim’s feedback was invaluable and conversations with him led to many of the ideas put forth; his comments and critiques enriched the work. Countless conversations with these two intelligent mentors helped focus and improve my work. I cannot thank them enough. I also benefitted from my superb dissertation committee. Its members provided important input and critique at various stages of research and writing. Ron Aminzade reminded me of the importance of considering a variety of forces in the study of social phenomena and his comments improved my arguments. Joseph Gerteis provided excellent suggestions on how to clarify of my arguments, suggested methods, and challenged me to strengthen the project in a variety of ways. I also thank Helga Leitner for her thoughtful critique and support over the years. During my time at the University of Minnesota, I took a number of excellent and intellectually stimulating classes and met a number of other faculty who left an impression and inspired me in a variety of ways including Jeffrey Broadbent, Liz Boyle, Robin Stryker, and Evan Schofer. -

Studia Regionalia

STUDIA REGIONALIA Journal of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Committee for Spatial Economy and Regional Planning & European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Polish Section Volume 51, 2017, pp. 51–67 doi: 10.12657/studreg-51-04 DYNAMICS AND VIABILITY OF CITY CENTRES – CONCEPTS, TOOLS, PROJECTS Adam Polko University of Economics in Katowice, Faculty of Economics, Department of Spatial and Environmental Economics; 1 Maja 50, 40-287 Katowice, Poland; [email protected] Abstract: The paper presents a review of concepts for the development of city centres in response to social and culture processes, economic, technical and environmental developments taking place at present on those areas. This review proves that concepts tend to change over time from those based on economic dynamics to those based on collaborative commons and on governance. On the example of a few city centres situated in the Silesian Region an analysis was carried out of the concepts being presently applied and with the use of which projects Silesian cities strive to maintain and strengthen the dynamics and vitality of city centres. Keywords: Creative city, gentrification, participatory governance, sharing city, urban commons, urban regeneration, vitality and viability of inner city. JEL codes: R10, R50 Introduction The town centre has always remained a subject of particular care both on the part of local authorities, and the inhabitants. It is a place where the most important municipal facilities and institutions are situated. It is also a place characterised by certain historical and culture values. What is more, it is also a place in which are representative public spaces that form certain hallmarks and the main reference point for persons visiting the city. -

Paths of Shrinkage in the Katowice Conurbation : Case Studies of Bytom and Sosnowiec Cities

Title: Paths of shrinkage in the Katowice Conurbation : case studies of Bytom and Sosnowiec cities Author: Robert Krzysztofik, Jerzy Runge, Iwona Kantor-Pietraga Citation style: Krzysztofik Robert, Runge Jerzy, Kantor-Pietraga Iwona. (2011). Paths of shrinkage in the Katowice Conurbation : case studies of Bytom and Sosnowiec cities. Sosnowiec : Wydział Nauk o Ziemi. Uniwersytet Śląski. Robert Krzysztofik Jerzy Runge Iwona Kantor-Pietraga Paths of Shrinkage in the Katowice Conurbation. Case Studies of Bytom and Sosnowiec Cities Sosnowiec 2011 Redaktor Prac Wydziału Nauk o Ziemi Uniwersytetu Śląskiego Prof. dr hab. Andrzej T. Jankowski Editor of The Dissertations of Earth Science Faculty, Silesian University Prof. dr Andrzej T. Jankowski Prace Wydziału Nauk o Ziemi Uniwersytetu Śląskiego nr 69 The Dissertations of Earth Science Faculty, Silesian University, no. 69 Recenzent: Review by: Prof. UJ dr hab. Andrzej Zborowski Prof. dr Andrzej Zborowski Uniwersytet Jagielloński w Krakowie The Jagiellonian University, Krakow Wydawca: Publish by: Wydział Nauk o Ziemi Faculty of Earth Science Uniwersytet Śląski University of Silesia Ul. Będzińska 60, 41-200 Sosnowiec 60, Będzińska Street, 41-200 Sosnowiec ISSN 1895-6777 ISBN 978-83-61644-21-7 Druk: Pracownia Komputerowa Jacka Skalmierskiego, Gliwice. Printing: The Jacek Skalmierski Computer Laboratory, Gliwice. Książka sfinansowana z budżetu projektu unijnego: Shrink Smart. Governance of Shrinkage within a European Context, nr 225193 This book has been published with the support of the EU Project: -

Silesia, Poland - Regional Profile 1

SILESIA, POLAND - REGIONAL PROFILE 1 REGIONAL PROFILE Silesia GENERAL INFORMATION Country: Poland Region Name: Silesia Region NUTS2 code*: PL22 - Silesia Region NUTS3 code PL22A - Katowicki / PL228 Bytomski PL229 - Gliwicki / PL227 - Rybnicki PL22B - Sosnowiecki / PL22C - Tyski Main urban centres in the region (by population): Katowice - 294,510 / Częstochowa - 222,292 Sosnowiec - 202,036 / Gliwice - 179,806 Zabrze - 173,374 / Bielsko-Biała - 171,259 Bytom - 166,795 / Rybnik - 138,696 Ruda Śląska - 138,000 / Tychy - 127,831 *NUTS: Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics NOTICE ON COVID-19 The data contained within this regional profile was primarily gathered prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. It is recognised that the pandemic has had an adverse impact on energy demand. Although the consequences and implications are significant, they remain emergent and dynamic. An update to this document should be considered, once these consequences and implications are clearer and more quantifiable. INITIATIVE FOR COAL REGIONS IN TRANSITION SILESIA, POLAND - REGIONAL PROFILE 2 Overview Silesia is the most populated and urbanised region in Poland with over 4.5 million inhabitants. 78% of its population live in cities and its population density is 370 people/km2. The region comprises of eight NUTS-3 subregions, out of which six are notably affected by coal mining and related industries. The communities where the majority of the miners live are located in central and western subregions - namely Katowicki subregion, Bytomski subregion, Gliwicki subregion, Rybnicki subregion, Sosnowiecki subregion, and Tyski subregion. Silesia is the most coal-dependent region in Poland with mining playing an important role in the regional economy. However, its gradual decline in recent years is also apparent as production is declining in view of falling productivity and low profitability. -

Changes in Population Density of the Urban Population in Southern Poland in the Period 1950-2011 Against the Background of Political and Economic Transformation

MISCELLANEA GEOGRAPHICA – RegIONal StuDIeS ON DeVelOpmeNt Vol. 21 • No. 3 • 2017 • pp. 107-113 • ISSN: 2084-6118 • DOI: 10.1515/mgrsd-2017-0017 Changes in population density of the urban population in southern Poland in the period 1950-2011 against the background of political and economic transformation Abstract This paper presents the changes in urban population density in Iwona Jażdżewska the twentieth and twenty-first centuries in an area of approximately 20,000 km2 in southern Poland, which includes close to 100 towns and cities with a population of almost 4.5 million (in 2011) and an urbanisation index over 70%. It is the most urbanised part of Poland and includes the Institute of Urban Geography and Tourism, Cracow agglomeration and the Upper Silesian conurbation. The analysis Faculty of Geographical Sciences, was performed using one of the statistical methods for estimating discrete University of Łódź, Poland e-mail: [email protected] distributions, the kernel function method. The conclusions served as a basis for the presentation of changes occurring in this area against the backdrop of political and economic transformation in Poland, as well as a scientific discussion concerning the state and future of the merging of these agglomerations in the light of the factors discussed. Keywords Cracow • Silesia • population density • political transformation • Kernel function Received: 1 July 2016 © University of Warsaw – Faculty of Geography and Regional Studies Accepted: 20 July 2017 Introduction Upper Silesia, covering the Dąbrowa Basin and the Cracow of depopulation of Upper Silesian cities and strong processes agglomeration,1 was the region with the highest density of urban of suburbanisation around Cracow, as well as discussing their networks and the highest population in Poland in both 1950 causes and the pace of change. -

Environmental and Social Data Sheet

Luxembourg, 9th November 2015 Environmental and Social Data Sheet Overview Project Name: UPPER SILESIA URBAN FRAMEWORK PROGRAMME Project Number: 2015-0075 Country: Poland Project Description: The project will support eligible investment schemes in nine cities of the Upper Silesian Agglomeration: Bytom, Chorzów, Dąbrowa Górnicza, Gliwice, Katowice, Ruda Śląska, Rybnik, Sosnowiec and Tychy. The operation supports urban development and infrastructure modernization, including investments aiming at linking and integrating the cities. EIA required: Multiple-scheme operation. Some of the schemes are likely to fall under Annex I or II of the EIA Directive and may be screened in. 1 Project included in Carbon Footprint Exercise : no (details for projects included are provided in section: “EIB Carbon Footprint Exercise”) Summary of Environmental and Social Assessment, including key issues and overall conclusion and recommendation The operation comprises multi-sector and multi-city investments in Bytom, Chorzów, Dąbrowa Górnicza, Gliwice, Katowice, Ruda Śląska, Rybnik, Sosnowiec and Tychy, located in the Upper Silesia Agglomeration (PL). The objectives are in line with those included in the respective Local Development Strategies and the Development Strategy for the Silesian Province: Silesia 2020+, for which the Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) was performed in compliance with the EU SEA Directive 2001/42/EC. The NTS of the SEA has been provided to the Bank. In addition, strategic environmental assessments were performed for the Development Strategies of Bytom, Gliwice and Rybnik, approved respectively in 2009, 2007 and 2015. The NTSs of these SEAs have been also provided to the Bank. The Development Strategies of Chorzow, Dąbrowa Gornicza, Katowice, Ruda Slaska, Sosnowiec and Tychy are in large measure aspirational policies and as such, do not fall under the scope of the SEA Directive 2001/42/EC. -

Wykaz Podmiotów Wykonujących Działalność Leczniczą Realizujących Szczepienia Przeciw COVID-19

Wykaz podmiotów wykonujących działalność leczniczą realizujących szczepienia przeciw COVID-19 szczepienie Podmiot wykonujący działalność leczniczą 1 szczepienie populacyjne personelu Samodzielny Publiczny Zakład Opieki Zdrowotnej Nazwa: Zespół Szpitali Miejskich w Chorzowie Adres: Chorzów 41-500, Strzelców Bytomskich 11 Telefon: (032)349 91 15 Identyfikator REGON: 271503410 szczepienie Miejsce udzielania świadczeń 1 liczba zespołów personelu* Nazwa: Adres: Chorzów 41-500, Strzelców Bytomskich 11 W Telefon: Data dodania do wykazu: 24.12.2020 Data wykreślenia z wykazu: szczepienie Podmiot wykonujący działalność leczniczą 2 szczepienie populacyjne personelu Zespół Opieki Zdrowotnej w Świętochłowicach Nazwa: Spółka z ograniczoną odpowiedzialnością Adres: Świętochłowice 41-605, Chorzowska 38 Telefon: 32 245 50 41 Identyfikator REGON: 311450 szczepienie Miejsce udzielania świadczeń 1 liczba zespołów personelu* Nazwa: Adres: Świętochłowice 41-605, Chorzowska 36 W Telefon: Data dodania do wykazu: 24.12.2020 Data wykreślenia z wykazu: szczepienie Podmiot wykonujący działalność leczniczą 3 szczepienie populacyjne personelu GÓRNOŚLĄSKIE CENTRUM MEDYCZNE IM. PROF. Nazwa: LESZKA GIECA ŚLĄSKIEGO UNIWERSYTETU MEDYCZNEGO W KATOWICACH Adres: Katowice 40-635, Ziołowa 45-47 Telefon: (032)359 80 00 Identyfikator REGON: 1262860 szczepienie Miejsce udzielania świadczeń 1 liczba zespołów personelu* Nazwa: Adres: Katowice 40-635, Ziołowa 45-47 W Telefon: Data dodania do wykazu: 24.12.2020 Data wykreślenia z wykazu: szczepienie Podmiot wykonujący działalność leczniczą -

Download/Strategia-Bytom-2020,44.Pdf/View (Accessed on 8 September 2020)

sustainability Article Does One Decade of Urban Policy for the Shrinking City Make Visible Progress in Urban Re-Urbanization? A Case Study of Bytom, Poland Iwona Kantor-Pietraga Institute of Social and Economic Geography and Spatial Management, University of Silesia in Katowice, 41-200 Sosnowiec, Poland; [email protected] Abstract: Planning and managing the declining fortunes of shrinking cities are essential in shaping urban policy in post-industrial urban societies, especially in Central and Eastern European states. Many studies emphasize city management and redevelopment as important policy constituencies for driving revitalization. However, there is still a lack of knowledge about policy-making and the underlying political and socio-economic disagreements that impact successful measures to reverse urbanization and regenerate post-industrial cities. This paper provides a case of urban policy-making for Bytom—a severely shrinking city in southern Poland. This article aims to clarify the mismatch between the city’s policy and the socio-economic situation Bytom after 2010. This discrepancy could have weakened effective policy to address shrinkage and revitalization. Statistical and cartographic methods (choropleth maps) helped analyze the socio-economic changes in Bytom and its shrinking. The issues related to the city’s policy were based primarily on free-form interviews and the analysis of municipal and regional documents concerning Bytom. The conducted research shows the need Citation: Kantor-Pietraga, I. Does for concerted and coordinated policy direction that considers the real possibilities of implementing One Decade of Urban Policy for the pro-development projects. Such expectations also result from the opinions of local communities. -

The Programming of Environmental Protection and the Programming of Balanced Development on the Level of Local Communities Has Been Shown in This Paper

Polish Journal of Environmental Studies Vol. 8, No. 5 (1999), 341-344 Letters to Editor The Programming of Environmental Protection and the Programming of Balanced Development in the Examples of Some Selected Districts B. Piontek Katowice University of Economics, Ecology and Environmental Economy Faculty - doctorial studies 1 Maja 50, 40-226 Katowice, Poland Received 12 May, 1998 Accepted 17 May, 1999 Abstract The relationship between the programming of environmental protection and the programming of balanced development on the level of local communities has been shown in this paper. In the development of both programs two planning formulaes, recommended by UNEP, may be applied, namely - masterplan and development scenarios. Out of the analysis of some selected districts development programs numerous conclusions, as presented, may be drawn. The most important one states that the programming of environmental protection should not be treated separately, but as a component of a balanced development program. Keywords: balanced development, masterplan, development scenarios. In the last decade, a lot of districts in Poland have There are some facts that create the background for begun to elaborate programs connected with environmental a deeper analysis of the programming of environmental protection and balanced development (ecodevelopment). protection and balanced development: For example, environmental protection programs have al- - this kind of programming is not the strong side of our ready been developed in Bytom, Radom and Elk. Ecodeve- districts. We can see this from numerous examples of ex lopment programs have also been created for The Federa- perts hired from abroad in order to elaborate the program tion of Szelmet district (Suwalk county), Krynki and Piecki mes of environmental protection and balanced develop districts (Bialystok county), the town of Rybnik, the town ment. -

Contested Identities and Symbolic Changes in the Urban Space of Bytom (Poland)

Journal of Geography, Politics and Society 2020, 10(4), 33–48 https://doi.org/10.26881/jpgs.2020.4.05 CONTESTED IDENTITIES AND SYMBOLIC CHANGES IN THE URBAN SPACE OF BYTOM (Poland). THE HISTORicAL-GeoGRAPHICAL APPROACH Marzena Lamparska Institute of Social and Economic Geography and Spatial Management, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Silesia, Będzińska 60, 41-205 Sosnowiec, Poland, ORCID: 0000-0001-8574-9253 e-mail: [email protected] Citation Lamparska M., 2020, Contested identities and symbolic changes in the urban space of Bytom (Poland). The historical-geo- graphical approach, Journal of Geography, Politics and Society, 10(4), 33–48. Abstract Bytom is a city located in Upper Silesia, in the southern part of Poland which after World War II found itself within the bounda- ries of Poland after several hundred years. For many centuries, the main function of the city has been metal-ore and hard coal mining, which considerably contributed to its historical identity. The over 800-year history is full of numerous social, economic and ethnic conflicts caused by frequent changes in the city’s political affiliation and frequent redefinitions of its identity. After the collapse of communism, during the political and economic transformation, there arose a need to determine a new de- velopment path, in particular a new perspective on the heritage from the times of German dominance and from the times of communism. The mining and heavy industries have already ceased to be the basis of Bytom’s identity. Taking account of these historical rationales, this article attempts to answer the question of whether, among a number of contradictions and conflicts, the urban community of today’s Bytom, heterogeneous in terms of its origin, will be able to generate a model of cultural iden- tity and historical remembrance accepted by all. -

Pojemniki-Slaskie.Pdf

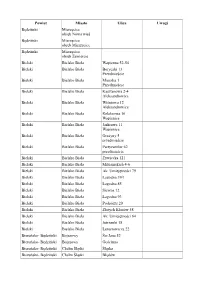

Powiat Miasto Ulica Uwagi Będziński Mierzęcice obręb Nowa wieś Będziński Mierzęcice obręb Mierzęcice Będziński Mierzęcice obręb Zawiercie Bielski Bielsko Biała Wapienna 52-54 Bielski Bielsko Biała Boryczki 13 Przedmieście Bielski Bielsko Biała Mieszka 1 Przedmieście Bielski Bielsko Biała Kasztanowa 2-4 Aleksandrowice Bielski Bielsko Biała Wiśniowa 12 Aleksandrowice Bielski Bielsko Biała Relaksowa 16 Wapienica Bielski Bielsko Biała Jaskrowa 11 Wapienica Bielski Bielsko Biała Grażyny 5 przedmieście Bielski Bielsko Biała Partyzantów 62 przedmieście Bielski Bielsko Biała Żywiecka 121 Bielski Bielsko Biała Milusińskich 4-6 Bielski Bielsko Biała Ak. Umiejętności 79 Bielski Bielsko Biała Łagodna 39/1 Bielski Bielsko Biała Łagodna 85 Bielski Bielsko Biała Siewna 12 Bielski Bielsko Biała Łagodna 93 Bielski Bielsko Biała Podgórze 20 Bielski Bielsko Biała Złotych Kłosów 58 Bielski Bielsko Biała Ak. Umiejętności 64 Bielski Bielsko Biała Jutrzenki 18 Bielski Bielsko Biała Lenartowicza 22 Bieruńsko- Będziński Bojszowy Św.Jana 52 Bieruńsko- Będziński Bojszowy Gościnna Bieruńsko- Będziński Chełm Śląski Śląska Bieruńsko- Będziński Chełm Śląski Błędów Bieruńsko- Będziński Chełm Śląski Techników Bieruńsko- Będziński Chełm Śląski Górnośląska Bieruńsko- Będziński Chełm Śląski Chełm Śląski Bytomski Bytom Fałata 5a Podwórko Bytomski Bytom Fałata 30 Podwórko Bytomski Bytom Akacjowa Bytomski Bytom Jaworowa Bytomski Bytom Woźniaka 63 Podwórko Bytomski Bytom Woźniaka 63 Podwórko Bytomski Bytom Woźniaka 47 Podwórko Bytomski Bytom Woźniaka 39 Podwórko Bytomski Bytom -

Between Germany, Poland and Szlonzokian Nationalism

EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION EUI Working Paper HEC No. 2003/1 The Szlonzoks and their Language: Between Germany, Poland and Szlonzokian Nationalism TOMASZ KAMUSELLA BADIA FIESOLANA, SAN DOMENICO (FI) All rights reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission of the author(s). © 2003 Tomasz Kamusella Printed in Italy in December 2003 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50016 San Domenico (FI) Italy ________Tomasz Kamusella________ The Szlonzoks1 and Their Language: Between Germany, Poland and Szlonzokian Nationalism Tomasz Kamusella Jean Monnet Fellow, Department of History and Civilization, European University Institute, Florence, Italy & Opole University, Opole, Poland Please send any comments at my home address: Pikna 3/2 47-220 Kdzierzyn-Koïle Poland [email protected] 1 This word is spelt in accordance with the rules of the Polish orthography and, thus, should be pronounced as /shlohnzohks/. 1 ________Tomasz Kamusella________ Abstract This article analyzes the emergence of the Szlonzokian ethnic group or proto- nation in the context of the use of language as an instrument of nationalism in Central Europe. When language was legislated into the statistical measure of nationality in the second half of the nineteenth century, Berlin pressured the Slavophone Catholic peasant-cum-worker population of Upper Silesia to become ‘proper Germans’, this is, German-speaking and Protestant. To the German ennationalizing2 pressure the Polish equivalent was added after the division of Upper Silesia between Poland and Germany in 1922. The borders and ennationalizing policies changed in 1939 when the entire region was reincorporated into wartime Germany, and, again, in 1945 following the incorporation of Upper Silesia into postwar Poland.