Abies Bracteata), a Relict of the Miocene Broadleaved Evergreen Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Journal by RICHARD E

Japanese Journal by RICHARD E. WEAVER, JR. ’ The aim of the Arnold Arboretum’s collecting trip to Japan and Korea in the fall of 1977 has already been explained briefly in the January- February issue of Arnoldia. The present article will describe in more detail our experiences in Japan; another in the next issue of Arnoldia will cover the Korean portion of the trip. Space allows for the de- scription of only the most memorable days, but a detailed itinerary with a list of the plants collected each day appears at the end of the article. Steve Spongberg and I left Logan International Airport 10 : 00 a.m. on September 1, and after changing planes in Chicago, headed for Tokyo. Our route took us across Canada’s Prairie Provinces, the southern Yukon Territory, and Alaska’s Coast Ranges to Anchorage. The views of the ice-clad peaks and glacier-filled valleys were spec- tacular and we had an enticing glimpse of Mt. McKinley on the horizon. After a frustrating hour at the Anchorage airport, we took off on the long last leg of our trip, arriving at our hotel approximately 15 hours after leaving Boston. The next morning was spent in the Ginza, the main shopping district, where everything was fascinating, particularly the flower and pro- duce shops. The former featured many standard items, but we found several surprises: One of the most common potted plants was a dwarf form of Gentiana scabra, a native Japanese gentian. Other gentians, particularly G. triflora var. japonica, a bottle-type, were sold as cut flowers. -

Qty Size Name 6 1G Abies Bracteata 10 1G Abutilon Palmeri 1 1G Acaena Pinnatifida Var

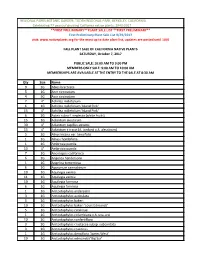

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 76 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2016 **FINAL**PLANT SALE LIST **FINAL** (9/30/2016 @ 6:00 PM) visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2016 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name 6 1G Abies bracteata 10 1G Abutilon palmeri 1 1G Acaena pinnatifida var. californica 18 1G Achillea millefolium 10 4" Achillea millefolium - Black Butte 28 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 8 4" Achillea millefolium 'Rosy Red' - donated by Annie's Annuals 2 4" Achillea millefolium 'Sonoma Coast' 7 4" Acmispon (Lotus) argophyllus var. argenteus 9 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) 25 4" Adiantum x tracyi (A. jordanii x A. aleuticum) 5 1G Aesculus californica 1 2G Agave shawii var. shawii 2 1G Agoseris grandiflora 8 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia 2 2G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia 5 4" Ambrosia pumila 5 1G Amelanchier alnifolia var. semiintegrifolia 9 1G Anemopsis californica 5 1G Angelica hendersonii 3 1G Angelica tomentosa 1 1G Apocynum androsaemifolium x Apocynum cannabinum 7 1G Apocynum cannabinum 5 1G Aquilegia formosa 2 4" Aquilegia formosa 4 4" Arbutus menziesii 2 1G Arctostaphylos andersonii 2 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata 3 1G Arctostaphylos 'Austin Griffith' 11 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 5 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens subsp. -

For More Than Forty Years, Japan Hes Been Cooperating with Partner Countries for Sustainable Forest Management

1. 2/3 OF APAN IS OVERED WITH ORESTS FOREST J C F RESOURCES CREATING A LAND OF GREENERY. ■ JAPAN 44° Japan is located at the eastern edge of the Eurasia, between longitudes of 123 and 149 degrees and latitudes 40° of 24 and 46 degrees. It is an archipelago extending over approximately 3,000 km from the Northeast to the 36° Southwest and land area of about 380,000 square kilometers. In general, the topography is very steep. Mountains ranging from 2,000-3,000 meters high form a 32° rugged backbone through the center of the country. 132° 136° 140° 1. Varietry of Forests Range from Sub-tropical forests to Alpine Forests. Japan has a wet monsoon climate and experiences distinct seasonal changes between the four seasons of spring, summer, autumn and winter. Also, meteorological conditions vary because of the latitudinal difference, dividing the forests into six types. Moreover, since high mountains range through the center of the country, it is possible to find vertical variation in forest types even in areas at the same latitude. Thus the forests are extremely rich in variation. ■ The Distribution of Japan’s Forests Atpine zone Sub-frigid forest Cool temperate coniferous forest mixed with broad-leaved trees Cool temperate forest Warm temperate forest Sub-tropical forest Sub-frigid forest ■ Effects of Altitude on Vegetation The example of Norikuradake mountain(3,026m) 3000m Pinus pumila Betula Ermanii Abies Mariesii Abies Veitchii 2000m Abies homolepis Fagus crenata Abies firma 1000m Cyclobalanopsis spp.(ever green oak). Sub-tropical forest 2 2/3 OF JAPAN IS COVERED WITH FORESTS Japanese cedar, REATING A AND OF REENERY. -

Big Sur Capital Preventive Maintenance (CAPM) Project Approximately a 35-Mile Section on State Route 1, from Big Sur to Carmel-By-The-Sea, in the County of Monterey

Big Sur Capital Preventive Maintenance (CAPM) Project Approximately a 35-mile section on State Route 1, from Big Sur to Carmel-by-the-Sea, in the County of Monterey 05-MON-01-PM 39.8/74.6 Project ID: 05-1400-0046 Project EA: 05-1F680 SCH#: 2018011042 Initial Study with Mitigated Negative Declaration Prepared by the State of California Department of Transportation April 2018 General Information About This Document The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), has prepared this Initial Study with Mitigated Negative Declaration, which examines the potential environmental impacts of the Big Sur CAPM project on approximately a 35-mile section of State Route 1, located in Monterey County California. The Draft Initial Study was circulated for public review and comment from January 26, 2018 to February 26, 2018. A Notice of Intent to Adopt a Mitigated Negative Declaration, and Opportunity for Public Hearing was published in the Monterey County Herald on Friday January 26, 2018. The Notice of Intent and Opportunity for Public Hearing was mailed to a list of stakeholders that included both government agencies and private citizen groups who occupy and have interest in the project area. No comments were received during the public circulation period. The project has completed the environmental compliance with circulation of this document. When funding is approved, Caltrans can design and build all or part of the project. Throughout this document, a vertical line in the margin indicates a change that has been made since the draft document -

The Role of Fir Species in the Silviculture of British Forests

Kastamonu Üni., Orman Fakültesi Dergisi, 2012, Özel Sayı: 15-26 Kastamonu Univ., Journal of Forestry Faculty, 2012, Special Issue The Role of True Fir Species in the Silviculture of British Forests: past, present and future W.L. MASON Forest Research, Northern Research Station, Roslin, Midlothian, Scotland EH25 9SY, U.K. E.mail:[email protected] Abstract There are no true fir species (Abies spp.) native to the British Isles: the first to be introduced was Abies alba in the 1600s which was planted on some scale until the late 1800s when it proved vulnerable to an insect pest. Thereafter interest switched to North American species, particularly grand (Abies grandis) and noble (Abies procera) firs. Provenance tests were established for A. alba, A. amabilis, A. grandis, and A. procera. Other silver fir species were trialled in forest plots with varying success. Although species such as grand fir have proved highly productive on favourable sites, their initial slow growth on new planting sites and limited tolerance of the moist nutrient-poor soils characteristic of upland Britain restricted their use in the afforestation programmes of the last century. As a consequence, in 2010, there were about 8000 ha of Abies species in Britain, comprising less than one per cent of the forest area. Recent species trials have confirmed that best growth is on mineral soils and that, in open ground conditions, establishment takes longer than for other conifers. However, changes in forest policies increasingly favour the use of Continuous Cover Forestry and the shade tolerant nature of many fir species makes them candidates for use with selection or shelterwood silvicultural systems. -

Conserving Europe's Threatened Plants

Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation By Suzanne Sharrock and Meirion Jones May 2009 Recommended citation: Sharrock, S. and Jones, M., 2009. Conserving Europe’s threatened plants: Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Botanic Gardens Conservation International, Richmond, UK ISBN 978-1-905164-30-1 Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW, UK Design: John Morgan, [email protected] Acknowledgements The work of establishing a consolidated list of threatened Photo credits European plants was first initiated by Hugh Synge who developed the original database on which this report is based. All images are credited to BGCI with the exceptions of: We are most grateful to Hugh for providing this database to page 5, Nikos Krigas; page 8. Christophe Libert; page 10, BGCI and advising on further development of the list. The Pawel Kos; page 12 (upper), Nikos Krigas; page 14: James exacting task of inputting data from national Red Lists was Hitchmough; page 16 (lower), Jože Bavcon; page 17 (upper), carried out by Chris Cockel and without his dedicated work, the Nkos Krigas; page 20 (upper), Anca Sarbu; page 21, Nikos list would not have been completed. Thank you for your efforts Krigas; page 22 (upper) Simon Williams; page 22 (lower), RBG Chris. We are grateful to all the members of the European Kew; page 23 (upper), Jo Packet; page 23 (lower), Sandrine Botanic Gardens Consortium and other colleagues from Europe Godefroid; page 24 (upper) Jože Bavcon; page 24 (lower), Frank who provided essential advice, guidance and supplementary Scumacher; page 25 (upper) Michael Burkart; page 25, (lower) information on the species included in the database. -

Details of Important Plants in Rpbg

DETAILS OF IMPORTANT PLANTS IN RPBG ABIES BRACTEATA. SANTA LUCIA OR BRISTLECONE FIR. PINACEAE, THE PINE FAMILY. A slender tree (especially in the wild) with skirts of branches and long glossy green spine-tipped needles with white stomatal bands underneath. Unusual for its sharp needles and pointed buds. Pollen cones borne under the branches between needles; seed cones short with long bristly bracts extending beyond scales and loaded with pitch, the cones at the top of the tree and shattering when ripe. One of the world’s rarest and most unique firs, restricted to steep limestone slopes in the higher elevations of the Santa Lucia Mountains. Easiest access is from Cone Peak Road at the top of the first ridge back of the ocean and reached from Nacimiento Ferguson Road. Signature tree at the Garden, and much fuller and attractive than in its native habitat. ACER CIRCINATUM. VINE MAPLE. SAPINDACEAE, THE SOAPBERRY FAMILY. Not a vine but a small deciduous tree found on the edge of conifer forests in northwestern California and the extreme northern Sierra (not a Bay Area species). Slow growing to perhaps 20 feet high with pairs of palmately lobed leaves that turn scarlet in fall, the lobes arranged like an expanded fan. Tiny maroon flowers in early spring followed by pairs of winged samaras that start pink and turn brown in late summer, the fruits carried on strong winds. A beautiful species very similar to the Japanese maple (A. palmatum) needing summer water and part-day shade, best in coastal gardens. A beautiful sight along the northern Redwood Highway in fall. -

Big Sur for Other Uses, See Big Sur (Disambiguation)

www.caseylucius.com [email protected] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Big Sur For other uses, see Big Sur (disambiguation). Big Sur is a lightly populated region of the Central Coast of California where the Santa Lucia Mountains rise abruptly from the Pacific Ocean. Although it has no specific boundaries, many definitions of the area include the 90 miles (140 km) of coastline from the Carmel River in Monterey County south to the San Carpoforo Creek in San Luis Obispo County,[1][2] and extend about 20 miles (30 km) inland to the eastern foothills of the Santa Lucias. Other sources limit the eastern border to the coastal flanks of these mountains, only 3 to 12 miles (5 to 19 km) inland. Another practical definition of the region is the segment of California State Route 1 from Carmel south to San Simeon. The northern end of Big Sur is about 120 miles (190 km) south of San Francisco, and the southern end is approximately 245 miles (394 km) northwest of Los Angeles. The name "Big Sur" is derived from the original Spanish-language "el sur grande", meaning "the big south", or from "el país grande del sur", "the big country of the south". This name refers to its location south of the city of Monterey.[3] The terrain offers stunning views, making Big Sur a popular tourist destination. Big Sur's Cone Peak is the highest coastal mountain in the contiguous 48 states, ascending nearly a mile (5,155 feet/1571 m) above sea level, only 3 miles (5 km) from the ocean.[4] The name Big Sur can also specifically refer to any of the small settlements in the region, including Posts, Lucia and Gorda; mail sent to most areas within the region must be addressed "Big Sur".[5] It also holds thousands of marathons each year. -

Potential Impact of Climate Change

Adhikari et al. Journal of Ecology and Environment (2018) 42:36 Journal of Ecology https://doi.org/10.1186/s41610-018-0095-y and Environment RESEARCH Open Access Potential impact of climate change on the species richness of subalpine plant species in the mountain national parks of South Korea Pradeep Adhikari, Man-Seok Shin, Ja-Young Jeon, Hyun Woo Kim, Seungbum Hong and Changwan Seo* Abstract Background: Subalpine ecosystems at high altitudes and latitudes are particularly sensitive to climate change. In South Korea, the prediction of the species richness of subalpine plant species under future climate change is not well studied. Thus, this study aims to assess the potential impact of climate change on species richness of subalpine plant species (14 species) in the 17 mountain national parks (MNPs) of South Korea under climate change scenarios’ representative concentration pathways (RCP) 4.5 and RCP 8.5 using maximum entropy (MaxEnt) and Migclim for the years 2050 and 2070. Results: Altogether, 723 species occurrence points of 14 species and six selected variables were used in modeling. The models developed for all species showed excellent performance (AUC > 0.89 and TSS > 0.70). The results predicted a significant loss of species richness in all MNPs. Under RCP 4.5, the range of reduction was predicted to be 15.38–94.02% by 2050 and 21.42–96.64% by 2070. Similarly, under RCP 8.5, it will decline 15.38–97.9% by 2050 and 23.07–100% by 2070. The reduction was relatively high in the MNPs located in the central regions (Songnisan and Gyeryongsan), eastern region (Juwangsan), and southern regions (Mudeungsan, Wolchulsan, Hallasan, and Jirisan) compared to the northern and northeastern regions (Odaesan, Seoraksan, Chiaksan, and Taebaeksan). -

Conifer Quarterly

Conifer Quarterly Vol. 24 No. 4 Fall 2007 Picea pungens ‘The Blues’ 2008 Collectors Conifer of the Year Full-size Selection Photo Credit: Courtesy of Stanley & Sons Nursery, Inc. CQ_FALL07_FINAL.qxp:CQ 10/16/07 1:45 PM Page 1 The Conifer Quarterly is the publication of the American Conifer Society Contents 6 Competitors for the Dwarf Alberta Spruce by Clark D. West 10 The Florida Torreya and the Atlanta Botanical Garden by David Ruland 16 A Journey to See Cathaya argyrophylla by William A. McNamara 19 A California Conifer Conundrum by Tim Thibault 24 Collectors Conifer of the Year 29 Paul Halladin Receives the ACS Annual Award of Merits 30 Maud Henne Receives the Marvin and Emelie Snyder Award of Merit 31 In Search of Abies nebrodensis by Daniel Luscombe 38 Watch Out for that Tree! by Bruce Appeldoorn 43 Andrew Pulte awarded 2007 ACS $1,000 Scholarship by Gerald P. Kral Conifer Society Voices 2 President’s Message 4 Editor’s Memo 8 ACS 2008 National Meeting 26 History of the American Conifer Society – Part One 34 2007 National Meeting 42 Letters to the Editor 44 Book Reviews 46 ACS Regional News Vol. 24 No. 4 CONIFER QUARTERLY 1 CQ_FALL07_FINAL.qxp:CQ 10/16/07 1:45 PM Page 2 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Conifer s I start this letter, we are headed into Afall. In my years of gardening, this has been the most memorable year ever. It started Quarterly with an unusually warm February and March, followed by the record freeze in Fall 2007 Volume 24, No 4 April, and we just broke a record for the number of consecutive days in triple digits. -

Qty Size Name 9 1G Abies Bracteata 5 1G Acer Circinatum 4 5G Acer

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 77 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2017 **FIRST PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **FIRST PRELIMINARY** First Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2017 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/6 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 7, 2017 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name 9 1G Abies bracteata 5 1G Acer circinatum 4 5G Acer circinatum 7 4" Achillea millefolium 6 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 15 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) 15 1G Adiantum aleuticum 30 4" Adiantum capillus-veneris 15 4" Adiantum x tracyi (A. jordanii x A. aleuticum) 5 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia 1 1G Alnus rhombifolia 1 1G Ambrosia pumila 13 4" Ambrosia pumila 7 1G Anemopsis californica 6 1G Angelica hendersonii 1 1G Angelica tomentosa 6 1G Apocynum cannabinum 10 1G Aquilegia eximia 11 1G Aquilegia eximia 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 6 1G Aquilegia formosa 1 1G Arctostaphylos andersonii 3 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata 5 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 10 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' 5 1G Arctostaphylos catalinae 1 1G Arctostaphylos columbiana x A. uva-ursi 10 1G Arctostaphylos confertiflora 3 1G Arctostaphylos crustacea subsp. subcordata 3 1G Arctostaphylos cruzensis 1 1G Arctostaphylos densiflora 'James West' 10 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Big Sur' 2 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Big Sur' 22 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii var. -

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ to Identify the Level of Threat to Plants

Ex-Situ Conservation at Scott Arboretum Public gardens and arboreta are more than just pretty places. They serve as an insurance policy for the future through their well managed ex situ collections. Ex situ conservation focuses on safeguarding species by keeping them in places such as seed banks or living collections. In situ means "on site", so in situ conservation is the conservation of species diversity within normal and natural habitats and ecosystems. The Scott Arboretum is a member of Botanical Gardens Conservation International (BGCI), which works with botanic gardens around the world and other conservation partners to secure plant diversity for the benefit of people and the planet. The aim of BGCI is to ensure that threatened species are secure in botanic garden collections as an insurance policy against loss in the wild. Their work encompasses supporting botanic garden development where this is needed and addressing capacity building needs. They support ex situ conservation for priority species, with a focus on linking ex situ conservation with species conservation in natural habitats and they work with botanic gardens on the development and implementation of habitat restoration and education projects. BGCI uses the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ to identify the level of threat to plants. In-depth analyses of the data contained in the IUCN, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, Red List are published periodically (usually at least once every four years). The results from the analysis of the data contained in the 2008 update of the IUCN Red List are published in The 2008 Review of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; see www.iucn.org/redlist for further details.