Lying, Secrecy, and Deceit Within Selected Works of Horatio Alger, Jr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

The Long Con of Civility

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Connecticut Law Review School of Law 2021 The Long Con of Civility Lynn Mie Itagaki Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review Recommended Citation Itagaki, Lynn Mie, "The Long Con of Civility" (2021). Connecticut Law Review. 446. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review/446 CONNECTICUT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 52 FEBRUARY 2021 NUMBER 3 Article The Long Con of Civility LYNN MIE ITAGAKI Civility has been much on the minds of pundits in local and national political discussions since the 1990s. Periods of civil unrest or irreconcilable divisions in governance intensify concerns about civility. While its more archaic definitions refer to citizenry and civilization, civility is often promoted as the foundation or goal of deliberative democracies. However, less acknowledged is its disciplinary, repressive effects in maintaining or deepening racial, gendered, heteronormative, and ableist hierarchies that distinguish some populations for full citizenship and others for partial rights and protections. In Part I, I examine a recent series of civility polls, their contradictory results, and how these contradictions can importantly expose the fissures of our contemporary moment and our body politic. In Part II, I describe the historical background of civility around race, gender, and sexuality and the unacknowledged difficulty in defining civility and incivility. In Part III, I extend this discussion to address the recent cases before the Supreme Court concerning LGBTQ+ employment discrimination and lack of accessibility. In conclusion, I identify what it would mean to analyze civility in terms of dignity on the basis of these cases about the equal rights and protections of their LGBTQ+ and disabled plaintiffs. -

Trails of the Gold Hunters in Northern Seas and on Mountain Passes. Five Passes to the Yukon Gold Fields

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons John Muir: A Reading Bibliography by Kimes John Muir Papers 10-1-1897 Trails of the Gold Hunters in Northern Seas and on Mountain Passes. Five Passes to the Yukon Gold Fields. John Muir's Letter on the Condition of the Trails. The Best Route Next Spring Will Be by the Way of Dyea. Skagway Pronounced the Worst, in Spite of Attempted Road-Building. Bread for Prospectors. As Well Take Drugs to Heaven as Medicines to Alaska, Says the Experienced Traveler. John Muir Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/jmb Recommended Citation Muir, John, "Trails of the Gold Hunters in Northern Seas and on Mountain Passes. Five Passes to the Yukon Gold Fields. John Muir's Letter on the Condition of the Trails. The Best Route Next Spring Will Be by the Way of Dyea. Skagway Pronounced the Worst, in Spite of Attempted Road-Building. Bread for Prospectors. As Well Take Drugs to Heaven as Medicines to Alaska, Says the Experienced Traveler." (1897). John Muir: A Reading Bibliography by Kimes. 239. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/jmb/239 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the John Muir Papers at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in John Muir: A Reading Bibliography by Kimes by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. .(d tu.rb the calmest co-rner of the country. ,n the doland ocean passages from Puget a ~ ext · · d nd ;ound. These are natural ship canals, a 1 en, Even at sea passlDg sh>ps are .stoppe a tl> usand' miles long that were slowly scul))- t ,gging. -

Do I Need to Worry About Security Updates to My Car???

Do I Need To Worry About Security Updates To My Car??? Sarah LaCroix - @punkrockgoth on the internet Hi! My name is Sarah! ● 3rd LongCon talk ● I like to talk about social issues in security and technology. ● My cat helped me with the slides. @abbycat204 on Instagram A lot has happened since my LongCon 2018 talk… ● Got my CCNA! ● Graduated from Red River College’s Business Information Technology program with honours! I adopted not one... @bootsandlilysneks on Instagram ...but two snakes! @bootsandlilysneks on Instagram (The cat adores them if you were wondering) @bootsandlilysneks on Instagram I moved! (twice) I got an awesome job! ● InfoSec Analyst at IC Group ● Doing compliance, security awareness & training and project management ● Learning a lot and loving my workplace ● Fun fact: IC Group is hiring I enjoy the long bus commute less. So I decided it was time to get my license ...but and buy a car. Yay perks of no longer Free parking at being a student! work and at home! How to buy a car ● Make some decisions: More detailed instructions may include mentions of: ○ What can you afford? ● VIN and Carfax ○ Buy or lease? ● Test drives ● Vehicle inspection ○ New or used? ● Warranty ● Safety ratings ● Consider quality, reliability & total cost of ownership No one said anything about software or security updates. No one mentioned security at all. Nothing I read about buying or maintaining a car mentioned it. The “car” people I knew didn’t mention anything about this. No one said anything about software or security updates. The “tech” people I knew said I was overthinking this and this isn’t an issue. -

Horatio Alger, Jr

Horatio Alger, Jr. 1 Horatio Alger, Jr. Horatio Alger, Jr. Born January 13, 1832 Chelsea, Massachusetts, U.S. Died July 18, 1899 (aged 67) Natick, Massachusetts, U.S. Pen name Carl Cantab Arthur Hamilton Caroline F. Preston Arthur Lee Putnam Julian Starr Occupation Author Nationality American Alma mater Harvard College, 1852 Genres Children's literature Notable work(s) Ragged Dick (1868) Horatio Alger, Jr. (January 13, 1832 – July 18, 1899) was a prolific 19th-century American author, best known for his many juvenile novels about impoverished boys and their rise from humble backgrounds to lives of middle-class security and comfort through hard work, determination, courage, and honesty. His writings were characterized by the "rags-to-riches" narrative, which had a formative effect on America during the Gilded Age. Alger's name is often invoked incorrectly as though he himself rose from rags to riches, but that arc applied to his characters, not to the author. Essentially, all of Alger's novels share the same theme: a young boy struggles through hard work to escape poverty. Critics, however, are quick to point out that it is not the hard work itself that rescues the boy from his fate, but rather some extraordinary act of bravery or honesty, which brings him into contact with a wealthy elder gentleman, who takes the boy in as a ward. The boy might return a large sum of money that was lost or rescue someone from an overturned carriage, bringing the boy—and his plight—to the attention of some wealthy individual. It has been suggested that this reflects Alger's own patronizing attitude to the boys he tried to help. -

Ragged Dick by Horatio Alger

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/5348/5348.txt The Project Gutenberg EBook of Ragged Dick, by Horatio Alger This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Ragged Dick Or, Street Life in New York with the Boot-Blacks Author: Horatio Alger Release Date: October 5, 2004 [EBook #5348] [Date last updated: May 1, 2006] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RAGGED DICK *** Digitized by Cardinalis Etext Press [C.E.K.] Prepared for Project Gutenberg by Andrew Sly RAGGED DICK; OR, STREET LIFE IN NEW YORK WITH THE BOOT-BLACKS. BY HORATIO ALGER JR. To Joseph W. Allen, at whose suggestion this story was undertaken, it is inscribed with friendly regard. PREFACE "Ragged Dick" was contributed as a serial story to the pages of the Schoolmate, a well-known juvenile magazine, during the year 1867. While in course of publication, it was received with so many evidences of favor that it has been rewritten and considerably enlarged, and is now presented to the public as the first volume of a series intended to illustrate the life and experiences of the friendless and vagrant children who are now numbered by thousands in New York and other cities. Several characters in the story are sketched from life. The necessary information has been gathered mainly from personal observation and conversations with the boys themselves. -

Horatio Alger , Jr. Frank´S Campaign Or the Farm And

HORATIO ALGER , JR. FRANK´S CAMPAIGN OR THE FARM AND THE CAMP 2008 – All rights reserved Non commercial use permitted FRANK'S CAMPAIGN OR THE FARM AND THE CAMP By HORATIO ALGER, JR. FRANK'S CAMPAIGN CHAPTER I. THE WAR MEETING The Town Hall in Rossville stands on a moderate elevation overlooking the principal street. It is generally open only when a meeting has been called by the Selectmen to transact town business, or occasionally in the evening when a lecture on temperance or a political address is to be delivered. Rossville is not large enough to sustain a course of lyceum lectures, and the townspeople are obliged to depend for intellectual nutriment upon such chance occasions as these. The majority of the inhabitants being engaged in agricultural pursuits, the population is somewhat scattered, and the houses, with the exception of a few grouped around the stores, stand at respectable distances, each encamped on a farm of its own. One Wednesday afternoon, toward the close of September, 1862, a group of men and boys might have been seen standing on the steps and in the entry of the Town House. Why they had met will best appear from a large placard, which had been posted up on barns and fences and inside the village store and postoffice. It ran as follows: WAR MEETING! The citizens of Rossville are invited to meet at the Town Hall, on Wednesday, September 24, at 3 P. M. to decide what measures shall be taken toward raising the town's quota of twenty-five men, under the recent call of the President of the United States. -

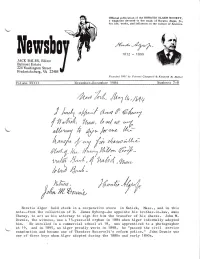

1984 Nov-Dec

Official publication of the HORATIO ALGER SOCIETY, a magazine devoted to the study of Horatio Alger, Jr., his life, works, and influence on the culture of America. 18)2 - 1899 Founded l96l by, Forresl Campbelt & Kenneth B. Butler Yolume )GIII November-December 1 984 Numbers 7-B &n,,t /./ ,fi^l /c,/Lf q / h*/, o/1,--/ A,u, f ,C, / /t /fr',il, fu**,, /o ail oa ur)/n r^^, /{; o[Cn,,y 6 U^ /,,r /to.,/n /, "^:/ f,f,,(^*7f, f/*/ ,7 l- //!,,,!,/ //*/t*^ 6,/ ^ ,lo,/ffi',,/k, ",'/, l "l,l o h n(, q/nor,, 'l /r rorD 6.*/ - ,1 hu/au ^ /6**t;4_r j,r{* //( bourl7 / Horatio Alger he1d. stock ln a cooperative store in Natick, Mass., and in this note--from the coll-ection of D. James Ryberg--he appoints his brother-in-law, Amos Cheney, to act as his attorney to sign for him the transfer of his shares. John M. Dorvnie, the witness, was u 15-yeur-o1d orphan in 1884 when Alger informally adopted him. He enrolled in a commercial school at 18, was apprenticed to a photographer aL 19, and in 1895, as Alger proudly wrote in 1898, he "passed the civil service examination and. became one of Theodore Booseveltts reform pol-ice." John Downie was one of three boys whom Alger adopted. during the 188Os and early 1890s. NEWSBOY HORATIO ALGNR SOCIETY LETTERS To further the phiosophy of Horatio Letters to the Eclitor are welcome, Alger, Jr., and to encourage the spirit but may be ed.ited or condensed clue to of Strive ani[ Succeed that for half a space l"imitations. -

“How the Hell Am I Normal?” “Pilot” Written by Adam F. Goldberg

! “How the Hell Am I Normal?” “Pilot” Written by Adam F. Goldberg Directed by Seth Gordon 2nd Rev. Network Draft – 11/27/12 Rev. Network Draft – 11/6/12 Network Draft – 10/23/12 Seth Gordon/Happy Madison/SPT/ABC SONY PICTURES TELEVISION INC. "© 2012" All Rights Reserved "No portion of this script may be performed, or reproduced by any means, or quoted, or published in any medium without prior written consent of SONY PICTURES TELEVISION INC. * 10202 West Washington Boulevard * Culver City, CA 90232*” How the Hell Am I Normal? "Pilot" 1. 2nd Rev. Network Draft 11.27.12 COLD OPEN 1980s STOCK FOOTAGE capturing happy suburban life. Kids ride Big Wheels, a dad teaches his son how to swing a bat, that famous home movie of the boy going ape-shit when his parents buy him a Nintendo at Christmas. ADULT ADAM (V.O.) Man, I miss the ‘80s. Not exactly the parachute pants or the keytar solos. No, I miss how back then the world was still small. No Internet or cell phone or Facebook or Tweets or Pings. Your friends lived on your street and your family were the people at your dinner table. They were all you had and all you needed... The STOCK FOOTAGE culminates with an idyllic ‘80s All-American family having a backyard barbecue complete with Slip N’ Slide. ADULT ADAM (V.O.) Unfortunately, I’ve got no clue who the hell these people are. No, no -- this is my family... SMASH TO OUR FAMILY SHOT IN VHS HOME FOOTAGE (A STAPLE WE’LL USE IN EVERY COLD OPEN): INT. -

Scarlet Widow Breaking Hearts for Profit Part 1: Nigeria-Based Romance Scam Operation Targets Vulnerable Populations

AGARI CYBER INTELLIGENCE DIVISION REPORT Scarlet Widow Breaking Hearts for Profit Part 1: Nigeria-Based Romance Scam Operation Targets Vulnerable Populations © 2019 Agari Data, Inc. Executive Summary Since 2017, Agari has been tracking and gathering intel on a Nigeria-based crime ring we’ve named Scarlet Widow. The group has a history of exploiting vulnerable populations, from romance scams against farmers and individuals with disabilities to wide- ranging business email compromise (BEC) attacks against organizations around the world. This report presents an in-depth look at This document is the first of two reports how the group’s romance scams work, and Agari has prepared on Scarlet Widow. The includes the heartbreaking case study of a second report, which will be released in late victim who was conned out of more than February 2019, covers more about the group’s $50,000. members and structure, their transition to BEC attacks, and how they launder their Scarlet Widow has mastered the seductive fraudulent proceeds. art of the romance scam, defrauding victims in the United States out of thousands of dollars through a prolific number of cons. In all romance scams had led to personal losses of nearly $1 billion in the US and Canada since 2015, according to research from the Better Business Bureau (BBB). And that’s only the crimes that get reported. In all actuality, this number is likely much larger. SCARLET WIDOW: BREAKING HEARTS FOR PROFIT FOR BREAKING HEARTS SCARLET WIDOW: AGARI | AGARI REPORT 2 Table of Contents Who is Scarlet Widow? -

Set Chair for Matthew Fox "Jack" 11 - 1,200 Set Chair for Matthew Fox "Jack." Wooden Director's C

200 Set chair for Matthew Fox "Jack" 11 - 1,200 Set chair for Matthew Fox "Jack." Wooden director's c... 300 200 Set chair for Evangeline Lilly "Kate" 2 - 1,500 Set chair for Evangeline Lilly "Kate." Wooden directo... 300 200 Set chair for Jorge Garcia "Hurley" 3 - 400 Set chair for Jorge Garcia "Hurley." Folding camping ... 300 200 Set chair for Terry O'Quinn "Locke" 4 - 1,700 Set chair for Terry O'Quinn "Locke." Wooden director'... 300 Set chair for Dominic Monaghan "Charlie" 200 5 Set chair for Dominic Monaghan "Charlie." Wooden - 600 dire... 300 200 Set chair for Emilie de Ravin "Claire" 6 - 550 Set chair for Emilie de Ravin "Claire." Wooden direct... 300 200 Set chair for Yunjin Kim "Sun" 7 - 800 Set chair for Yunjin Kim "Sun." Wooden director's cha... 300 Set chair for Naveen Andrews "Sayid" 200 8 Set chair for Naveen Andrews "Sayid." Wooden - 850 director... 300 200 Set chair for Harold Perrineau "Michael" 9 - 375 Set chair for Harold Perrineau "Michael." Wooden dire... 300 200 Set chair for Michael Emerson "Ben" 10 - 1,900 Set chair for Michael Emerson "Ben." Wooden director'... 300 200 Set chair for Nestor Carbonell "Richard Alpert" 11 - 850 Set chair for Nestor Carbonell "Richard Alpert." Wood... 300 200 Set chair for Elizabeth Mitchell "Juliet" 12 - 2,000 Set chair for Elizabeth Mitchell "Juliet." Wooden dir... 300 Set chair for Jeremy Davies "Faraday" 200 13 Set chair for Jeremy Davies "Faraday." Wooden - 950 directo... 300 Chair back from on-set chair for Alan Dale "Widmore" 100 14 Chair back from on-set chair for Alan Dale - 375 "Widmore.".. -

A Romance with the American Dream

сourse: A Romance with the American Dream How to Become “Healthy, Wealthy and Wise” -- A Discussion of Dreams and Success in 19th-century American Literature Author: I.V.Morozova Just think of all the self-help and personal growth programs that have appeared in the past couple of years! There are spiritual development trainings, trainings on how to grow stronger and develop self-confidence, how to take control of your life, or simply personal development. There are a lot of names, but the essence is the same, and few stop to think that all these programs are just modern versions of the idea of self-help and self-development that arose in the 19th century, not without some help from America. The concept of self-help was explained by Scotsman Samuel Smiles (1812-1904) in his book Self- Help; with Illustrations of Character and Conduct (1859). In his work, Smiles talks about the necessity of developing and maintaining moral purity in oneself, which must be combined with an active life, hard physical labor, a thirst for knowledge, and perseverance in accomplishing one’s goals. Samuel Smiles Sir George Reid © National Portrait Gallery The book contained biographies of well-known European industrialists and inventors, whose entire lives were a testament to this postulate. Smiles showed that “Liberty is quite as much a moral as a political growth — the result of free individual action, energy, and independence… It may be of comparatively little consequence how a man is governed from without, whilst everything depends upon how he governs himself from within.” The book became a bestseller in America: the author’s thoughts accorded well with the American view of life, where everyone relied solely on himself.