Horatio Alger and American Political Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horatio Alger, Jr

Horatio Alger, Jr. 1 Horatio Alger, Jr. Horatio Alger, Jr. Born January 13, 1832 Chelsea, Massachusetts, U.S. Died July 18, 1899 (aged 67) Natick, Massachusetts, U.S. Pen name Carl Cantab Arthur Hamilton Caroline F. Preston Arthur Lee Putnam Julian Starr Occupation Author Nationality American Alma mater Harvard College, 1852 Genres Children's literature Notable work(s) Ragged Dick (1868) Horatio Alger, Jr. (January 13, 1832 – July 18, 1899) was a prolific 19th-century American author, best known for his many juvenile novels about impoverished boys and their rise from humble backgrounds to lives of middle-class security and comfort through hard work, determination, courage, and honesty. His writings were characterized by the "rags-to-riches" narrative, which had a formative effect on America during the Gilded Age. Alger's name is often invoked incorrectly as though he himself rose from rags to riches, but that arc applied to his characters, not to the author. Essentially, all of Alger's novels share the same theme: a young boy struggles through hard work to escape poverty. Critics, however, are quick to point out that it is not the hard work itself that rescues the boy from his fate, but rather some extraordinary act of bravery or honesty, which brings him into contact with a wealthy elder gentleman, who takes the boy in as a ward. The boy might return a large sum of money that was lost or rescue someone from an overturned carriage, bringing the boy—and his plight—to the attention of some wealthy individual. It has been suggested that this reflects Alger's own patronizing attitude to the boys he tried to help. -

Ragged Dick by Horatio Alger

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/5348/5348.txt The Project Gutenberg EBook of Ragged Dick, by Horatio Alger This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Ragged Dick Or, Street Life in New York with the Boot-Blacks Author: Horatio Alger Release Date: October 5, 2004 [EBook #5348] [Date last updated: May 1, 2006] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RAGGED DICK *** Digitized by Cardinalis Etext Press [C.E.K.] Prepared for Project Gutenberg by Andrew Sly RAGGED DICK; OR, STREET LIFE IN NEW YORK WITH THE BOOT-BLACKS. BY HORATIO ALGER JR. To Joseph W. Allen, at whose suggestion this story was undertaken, it is inscribed with friendly regard. PREFACE "Ragged Dick" was contributed as a serial story to the pages of the Schoolmate, a well-known juvenile magazine, during the year 1867. While in course of publication, it was received with so many evidences of favor that it has been rewritten and considerably enlarged, and is now presented to the public as the first volume of a series intended to illustrate the life and experiences of the friendless and vagrant children who are now numbered by thousands in New York and other cities. Several characters in the story are sketched from life. The necessary information has been gathered mainly from personal observation and conversations with the boys themselves. -

Horatio Alger , Jr. Frank´S Campaign Or the Farm And

HORATIO ALGER , JR. FRANK´S CAMPAIGN OR THE FARM AND THE CAMP 2008 – All rights reserved Non commercial use permitted FRANK'S CAMPAIGN OR THE FARM AND THE CAMP By HORATIO ALGER, JR. FRANK'S CAMPAIGN CHAPTER I. THE WAR MEETING The Town Hall in Rossville stands on a moderate elevation overlooking the principal street. It is generally open only when a meeting has been called by the Selectmen to transact town business, or occasionally in the evening when a lecture on temperance or a political address is to be delivered. Rossville is not large enough to sustain a course of lyceum lectures, and the townspeople are obliged to depend for intellectual nutriment upon such chance occasions as these. The majority of the inhabitants being engaged in agricultural pursuits, the population is somewhat scattered, and the houses, with the exception of a few grouped around the stores, stand at respectable distances, each encamped on a farm of its own. One Wednesday afternoon, toward the close of September, 1862, a group of men and boys might have been seen standing on the steps and in the entry of the Town House. Why they had met will best appear from a large placard, which had been posted up on barns and fences and inside the village store and postoffice. It ran as follows: WAR MEETING! The citizens of Rossville are invited to meet at the Town Hall, on Wednesday, September 24, at 3 P. M. to decide what measures shall be taken toward raising the town's quota of twenty-five men, under the recent call of the President of the United States. -

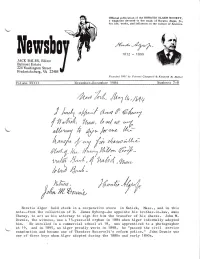

1984 Nov-Dec

Official publication of the HORATIO ALGER SOCIETY, a magazine devoted to the study of Horatio Alger, Jr., his life, works, and influence on the culture of America. 18)2 - 1899 Founded l96l by, Forresl Campbelt & Kenneth B. Butler Yolume )GIII November-December 1 984 Numbers 7-B &n,,t /./ ,fi^l /c,/Lf q / h*/, o/1,--/ A,u, f ,C, / /t /fr',il, fu**,, /o ail oa ur)/n r^^, /{; o[Cn,,y 6 U^ /,,r /to.,/n /, "^:/ f,f,,(^*7f, f/*/ ,7 l- //!,,,!,/ //*/t*^ 6,/ ^ ,lo,/ffi',,/k, ",'/, l "l,l o h n(, q/nor,, 'l /r rorD 6.*/ - ,1 hu/au ^ /6**t;4_r j,r{* //( bourl7 / Horatio Alger he1d. stock ln a cooperative store in Natick, Mass., and in this note--from the coll-ection of D. James Ryberg--he appoints his brother-in-law, Amos Cheney, to act as his attorney to sign for him the transfer of his shares. John M. Dorvnie, the witness, was u 15-yeur-o1d orphan in 1884 when Alger informally adopted him. He enrolled in a commercial school at 18, was apprenticed to a photographer aL 19, and in 1895, as Alger proudly wrote in 1898, he "passed the civil service examination and. became one of Theodore Booseveltts reform pol-ice." John Downie was one of three boys whom Alger adopted. during the 188Os and early 1890s. NEWSBOY HORATIO ALGNR SOCIETY LETTERS To further the phiosophy of Horatio Letters to the Eclitor are welcome, Alger, Jr., and to encourage the spirit but may be ed.ited or condensed clue to of Strive ani[ Succeed that for half a space l"imitations. -

A Romance with the American Dream

сourse: A Romance with the American Dream How to Become “Healthy, Wealthy and Wise” -- A Discussion of Dreams and Success in 19th-century American Literature Author: I.V.Morozova Just think of all the self-help and personal growth programs that have appeared in the past couple of years! There are spiritual development trainings, trainings on how to grow stronger and develop self-confidence, how to take control of your life, or simply personal development. There are a lot of names, but the essence is the same, and few stop to think that all these programs are just modern versions of the idea of self-help and self-development that arose in the 19th century, not without some help from America. The concept of self-help was explained by Scotsman Samuel Smiles (1812-1904) in his book Self- Help; with Illustrations of Character and Conduct (1859). In his work, Smiles talks about the necessity of developing and maintaining moral purity in oneself, which must be combined with an active life, hard physical labor, a thirst for knowledge, and perseverance in accomplishing one’s goals. Samuel Smiles Sir George Reid © National Portrait Gallery The book contained biographies of well-known European industrialists and inventors, whose entire lives were a testament to this postulate. Smiles showed that “Liberty is quite as much a moral as a political growth — the result of free individual action, energy, and independence… It may be of comparatively little consequence how a man is governed from without, whilst everything depends upon how he governs himself from within.” The book became a bestseller in America: the author’s thoughts accorded well with the American view of life, where everyone relied solely on himself. -

Horatio Alger Jr. Biography

The Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans, Inc. 99 Canal Center Plaza • Suite 320 • Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone: 703-684-9444 • Fax: 703-684-9445 www.horatioalger.org FOREWORD MISSION OF THE HORATIO ALGER ASSOCIATION The “rags to riches” stories that Horatio Alger, Jr., wrote more than 100 years ago taught The Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans has inducted more than 600 the young people of his time that success would come to those who worked hard and Members since its formation in 1947. Having overcome adversity to achieve success in persevered through difficult circumstances. But those stories resonated far longer than their chosen careers, Members serve as role models for young people. In addition to oFne generation. In 1o947, whern Kenneeth Beewbe and NormanoVincentrPeale tad lked about Mdemonstrating that the Aimeriscan Dresam is aittainaoble, Men mbers provide college forming a group to infuse the American “can-do spirit” into the youth of their time, they scholarships to students who have struggled with adversity and know that higher felt naming their organization after Horatio Alger, Jr., said it all. education is key to a better future. The Association now awards more than $7 million annually in need-based scholarships. Since 1984, it has awarded almost $70 million The Members of this Association are primary examples of what can be accomplished in scholarships. with individual effort, diligence, and self-reliance—traits that were shared by main characters in Horatio Alger’s books. Just as his fictional stories inspired readers, our The Association is deeply grateful to its Members and friends who are committed to Association is working to do much the same thing through the real life stories of our advancing its mission: Members, which makes them all the more inspiring. -

60Th-Anniversary-Boo

HORATIO ALGER ASSOCIATION of DISTINGUISHED AMERICANS, INC. A SIXTY-YEAR HISTORY Ad Astra Per Aspera – To the Stars Through Difficulties 1947 – 2007 Craig R. Barrett James A. Patterson Louise Herrington Ornelas James R. Moffett Leslie T. Welsh* Thomas J. Brokaw Delford M. Smith Darrell Royal John C. Portman, Jr. Benjy F. Brooks* Jenny Craig Linda G. Alvarado Henry B. Tippie John V. Roach Robert C. Byrd Sid Craig Wesley E. Cantrell Herbert F. Boeckmann, II Kenny Rogers Gerald R. Ford, Jr. Craig Hall John H. Dasburg Jerry E. Dempsey Art Buchwald Paul Harvey Clarence Otis, Jr. Archie W. Dunham Joe L. Dudley, Sr. S. Truett Cathy Thomas W. Landry* Richard M. Rosenberg Bill Greehey Ruth Fertel* Robert H. Dedman* Ruth B. Love David M. Rubenstein Chuck Hagel Quincy Jones Julius W. Erving J. Paul Lyet* Howard Schultz James V. Kimsey Dee J. Kelly Daniel K. Inouye John H. McConnell Roger T. Staubach Marvin A. Pomerantz John Pappajohn Jean Nidetch Fred W. O’Green* Christ Thomas Sullivan Franklin D. Raines Don Shula Carl R. Pohlad Willie Stargell* Kenneth Eugene Behring Stephen C. Schott Monroe E. Trout D.B. Reinhart* Henry Viscardi, Jr.* Doris K. Christopher Philip Anschutz Dennis R. Washington Robert H. Schuller William P. Clements, Jr. Peter M. Dawkins Carol Bartz Joe L. Allbritton Romeo J. Ventres John B. Connally, Esq.* J. R. “Rick” Hendrick, III Arthur A. Ciocca Walter Anderson Carol Burnett Nicholas D’Agostino* Richard O. Jacobson Thomas C. Cundy Dwayne O. Andreas Trammell Crow Helen M. Gray* Harold F. “Gerry” Lenfest William J. Dor Dorothy L. Brown Robert J. -

Robinson Curriculum Book List Some Titles and Authors Have Been Corrected Or Expanded from the Original List

Robinson Curriculum Book List Some titles and authors have been corrected or expanded from the original list. REQUIRED BOOKS 1. McGuffey's Eclectic Primer - William McGuffey 2. McGuffey's First Eclectic Reader - William McGuffey 3. Nursery Rhymes (Altemus' Wee Books) - Various Authors 4. The Life of George Washington - Josephine Pollard 5. McGuffey's Second Eclectic Reader - William McGuffey 6. The Tale of Jolly Robin - Arthur Scott Bailey 7. The Tale of Solomon Owl - Arthur Scott Bailey 8. Our Hero General U. S. Grant - Josephine Pollard 9. The Tale of Paddy Muskrat - Arthur Scott Bailey 10. The Bobbsey Twins at School - Laura Lee Hope 11. Childhood's Happy Hours - O. M. Dunham 12. Christopher Columbus and the Discovery of the New World - Josephine Pollard 13. Young Folks' Bible - Josephine Pollard 14. Fifty Famous Stories Retold - James Baldwin 15. Four American Naval Heroes - Mabel Borton Beebe 16. The Rover Boys on the Great Lakes - Arthur Winfield (Edward Stratemeyer) 17. The Rover Boys on the River - Arthur Winfield (Edward Stratemeyer) 18. Five Little Peppers and How They Grew - Margaret Sidney 19. Five Little Peppers Midway - Margaret Sidney 20. The Rover Boys at College - Arthur Winfield (Edward Stratemeyer) 21. Tom Swift and His Airship - Victor Appleton 22. The Rover Boys on the Ocean - Arthur Winfield (Edward Stratemeyer) 23. Tom Swift and His Air Scout - Victor Appleton 24. The Adventures of Pinocchio (or A Tale of a Puppet) - C. Collodi 25. The Rover Boys on a Tour - Arthur Winfield (Edward Stratemeyer) 26. The Swiss Family Robinson - Johann David Wyss 27. The Rover Boys on Treasure Isle - Arthur Winfield (Edward Stratemeyer) 28. -

Why Speak of American Stories As Dreams? Cara Erdheim Sacred Heart University, [email protected]

Sacred Heart University DigitalCommons@SHU English Faculty Publications English Department 2013 Why Speak of American Stories as Dreams? Cara Erdheim Sacred Heart University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/eng_fac Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Erdheim, Cara, "Why Speak of American Stories as Dreams?" (2013). English Faculty Publications. Paper 19. http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/eng_fac/19 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Why Speak of American Stories as Dreams? Cara Erdheim The term “American Dream” conjures literary images of perseverance and promise on the one hand but disillusionment and defeat on the other: Ben Franklin pulling himself up by the bootstraps, Huck Finn “lighting out” for the territories, Gatsby insisting that he can “repeat the past,” Willy Loman burying his face in his hands. Whether one ac- cepts it as a reality, punctures it as a myth, or presents it as a nightmare, the American Dream has maintained its powerful presence in scholarly conversations throughout the decades. Traditionally, scholars have re- ferred to classic American Dream texts such as Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography (1791–1790), Horatio Alger’s Ragged Dick (1868), F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), and Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman (1949). In their readings of these works, early critics tended to associate the dream with a pervasive American spirit, a belief in national innocence, and a vision of human perfectibility; while later scholars challenge these traditional mobility narratives, some contem- porary critics deny that the dream ever existed in the first place. -

Rediscovering Alger Rediscovering Alger

Rediscovering Alger Rediscovering Alger by Carol Nackenoff I began to think about writing about Alger without a very clear understanding of why I had gotten "hooked" late in my graduate school years. I had written a dissertation on how different segments of the workforce's experiences with changes in the post-World War II U.S. job structure affected their political attitudes, attachments, and agendas. But I became convinced that survey research was not the best way to get at "worldviews"--understandings of how the world worked. I combatted a long "writer's block" with what I thought would be an article on Alger. Six years later, I signed a book contract with Oxford University Press. And I realized, along the way, how this work united my background in political theory, American political thought, political economy, my love of literature, and even literary theory; I also realized how it got at the patterning of American politics, in which I had long been interested. Why my title: "Rediscovering Alger"? I want to share three things with you. First, as collectors and Alger enthusiasts, I thought you might like to hear a few words about some of the finds or gems I discovered while travelling to collections from Boston to California--and sources that helped me think about Alger that aren't often examined. Second are some of the new insights and perspectives I gained on Alger, when Alger scholarship has been served so very ably by authors such as Ralph Gardner and by Gary Scharnhorst of the University of New Mexico, writing sometimes with Jack Bales. -

Alger, Horatio, Jr

24 ALCOHOL Rorabaugh, W. J. The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition. capitalist marketplace. As an author of popular fi ction, New Yo rk: Oxford University Press, 1979. Alger's own livelihood was uncertain, and he had to cater to mass-marketing structures and an emerging commodity RELATED ENTRIES culture in order to succeed. While his stories often celebrate Advice Literature; Artisan; Fraternal Organizations; the small producer values of a bygone past, the sentimental Immigration.; Industrialization; Leisure; Male Friendship; Men's relation between the wealthy patron and the plucky boy in Clubs; Middle-Class Manhood; Republicanism; Self-Control; Alger's stories, which have a decidedly homoerotic tone, can Sports; Suffragism; Temperance; Urbanization; Wo rk; Working be read as a support of capitalist class and market struc Class Manhood tures. By providing guidance and counsel and opening a -Wa lter F. Bell path toward economic opportunity, the businessmen in Alger's stories almost always uplift and assimilate the "gen tle boys" (who are also potential future members of "the ALGER, HORATIO, JR. dangerous classes") into the ranks of the petit bourgeoisie. As their reward, the protagonists achieve a modest degree of 1832-1899 social mobility offered by an emerging corporate, capitalist Author order, but never gain great wealth, fo r which they do not The author of over one hundred novels, Horatio Alger, Jr., has express a desire. Excluding women from the plots, Alger's come to be associated with a rags-to-riches narrative that stories affirm capitalism as a male enterprise and the mar combines moral uplift with social mobility. -

English 286: American Bestsellers T/TR 1:30-2:45 Peter Conn [email protected] / 215.898.5726 Office Hours: T/TH 3:30-5:00 and by Appt

English 286: American Bestsellers T/TR 1:30-2:45 Peter Conn [email protected] / 215.898.5726 Office hours: T/TH 3:30-5:00 and by appt. (FBH 313) Bestselling novels were long considered unworthy of serious study: they were (and are) typically plot-driven, often melodramatic, featured (and feature) characters that barely occupy one dimension much less three, and were (and are) written in prose that fails the stylistic tests that the Literary Establishment (whatever that is) has tended (and tends) to apply. Over the past twenty or so years, bestsellers have been treated to increased scrutiny (if not respect) as scholars have acknowledged the value of paying attention to books that have actually been read: sometimes by hundreds of thousands or even millions of people. Bestsellers can enlarge our understanding of the reach and range of the American literary imagination, and perhaps also illuminate our complex national past. Testing these hypotheses, the course will take up a sequence of best-selling American novels, beginning with James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, and ending with Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code. When a film or television adaptation is available, we will take a comparative look at that. We will also read one genre-bending bestseller, Maxine Hong Kingston’s Woman Warrior (1975), and one non-fiction bestseller, Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People. I will from time to time comment on texts beyond our reading list. The final selections will be chosen in consultation with the class members.