What the Rejection of Anwar Ibrahim's Petition for Pardon Tells

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada's G8 Plans

Plans for the 2010 G8 Muskoka Summit: June 25-26, 2010 Jenilee Guebert Director of Research, G8 Research Group, with Robin Lennox and other members of the G8 Research Group June 7, 2010 Plans for the 2010 G8 Muskoka Summit: June 25-26, Ministerial Meetings 31 2010 1 G7 Finance Ministers 31 Abbreviations and Acronyms 2 G20 Finance Ministers 37 Preface 2 G8 Foreign Ministers 37 Introduction: Canada’s 2010 G8 2 G8 Development Ministers 41 Agenda: The Policy Summit 3 Civil Society 43 Priority Themes 3 Celebrity Diplomacy 43 World Economy 5 Activities 44 Climate Change 6 Nongovernmental Organizations 46 Biodiversity 6 Canada’s G8 Team 48 Energy 7 Participating Leaders 48 Iran 8 G8 Leaders 48 North Korea 9 Canada 48 Nonproliferation 10 France 48 Fragile and Vulnerable States 11 United States 49 Africa 12 United Kingdom 49 Economy 13 Russia 49 Development 13 Germany 49 Peace Support 14 Japan 50 Health 15 Italy 50 Crime 20 Appendices 50 Terrorism 20 Appendix A: Commitments Due in 2010 50 Outreach and Expansion 21 Appendix B: Facts About Deerhurst 56 Accountability Mechanism 22 Preparations 22 Process: The Physical Summit 23 Site: Location Reaction 26 Security 28 Economic Benefits and Costs 29 Benefits 29 Costs 31 Abbreviations and Acronyms AU African Union CCS carbon capture and storage CEIF Clean Energy Investment Framework CSLF Carbon Sequestration Leadership Forum DAC Development Assistance Committee (of the Organisation for Economic Co- operation and Development) FATF Financial Action Task Force HAP Heiligendamm L’Aquila Process HIPC heavily -

Malaysia 2019 Human Rights Report

MALAYSIA 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Malaysia is a federal constitutional monarchy. It has a parliamentary system of government selected through regular, multiparty elections and is headed by a prime minister. The king is the head of state, serves a largely ceremonial role, and has a five-year term. Sultan Muhammad V resigned as king on January 6 after serving two years; Sultan Abdullah succeeded him that month. The kingship rotates among the sultans of the nine states with hereditary rulers. In 2018 parliamentary elections, the opposition Pakatan Harapan coalition defeated the ruling Barisan Nasional coalition, resulting in the first transfer of power between coalitions since independence in 1957. Before and during the campaign, then opposition politicians and civil society organizations alleged electoral irregularities and systemic disadvantages for opposition groups due to lack of media access and malapportioned districts favoring the then ruling coalition. The Royal Malaysian Police maintain internal security and report to the Ministry of Home Affairs. State-level Islamic religious enforcement officers have authority to enforce some criminal aspects of sharia. Civilian authorities at times did not maintain effective control over security forces. Significant human rights issues included: reports of unlawful or arbitrary killings by the government or its agents; reports of torture; arbitrary detention; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary or unlawful interference with privacy; reports of problems with -

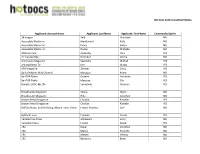

Hot Docs 2016 Accredited Media Applicant: Account Name Applicant: Last Name Applicant: First Name Community Opt-In 24 Images

Hot Docs 2016 Accredited Media Applicant: Account Name Applicant: Last Name Applicant: First Name Community Opt-In 24 images Selb Charlotte NO Accessible Media Inc. MacDonald Kelly NO Accessible Media Inc. Evans Simon NO Accessible Media Inc. Dudas Michelle NO Afisharu.com Zaslavsky Nina YES Air Canada Rep González Leticia NO Alternavox Magazine Saavedra Mikhail YES Arirang Korea TV Kim Mingu YES ATK Magazine Zimmer Cindy YES Balita/Filipino Web Channel Marquez Romy NO BanTOR Radio Qorane Nuruddin YES BanTOR Radio Mazzuca Ola YES Braidio, CKDU 88.1fm Simmonds Veronica YES Broadcaster Magazine Shane Myles NO Broadcaster Magazine Hiltz Jonathan NO Broken Pencil Magazine Charkot Richelle YES Broken Pencil Magazine Charkot Richelle YES Buffalo News, Buffalo Rising, Albany Times Union Francis Penders Carl NO ByBlacks.com Franklin Nicole YES Canada Free Press Anklewicz Larry NO Canadian Press Friend David YES CBC Dekel Jonathan NO CBC Mattar Pacinthe NO CBC Mesley Wendy NO CBC Bambury Brent NO Hot Docs 2016 Accredited Media CBC Tremonti Anna Maria NO CBC Galloway Matt NO CBC Pacheco Debbie NO CBC Berry Sujata NO CBC Deacon Gillian NO CBC Rundle Lisa NO CBC Kabango Shadrach NO CBC Berube Chris YES CBC Callender Tyrone YES CBC Siddiqui Tabassum NO CBC Mitton Peter YES CBC Parris Amanda YES CBC Reid Tashauna NO CBC Hosein Lise NO CBC Sumanac-Johnson Deana NO CBC Knegt Peter YES CBC Thompson Laura NO CBC Matlow Rachel NO CBC Coulton Brian NO CBC Hopton Alice NO CBC Cochran Cate YES CBC - Out in the Open Guillemette Daniel NO CBC / TVO Chattopadhyay Piya NO CBC Arts Candido Romeo YES CBC MUSIC FRENETTE BRAD NO CBC MUSIC Cowie Del NO CBC Radio Nazareth Errol NO CBC Radio Wachtel Eleanor NO Channel Zero Inc. -

Pollutant-Absorbing Plants to Clean up Sungai

Headline Pollutant-absorbing plants to clean up Sungai Rui MediaTitle The Star Date 12 Apr 2019 Color Full Color Section Metro Circulation 175,986 Page No 4 Readership 527,958 Language English ArticleSize 433 cm² Journalist IVAN LOH AdValue RM 21,791 Frequency Daily PR Value RM 65,373 >n i. Pollutant-absorbing plants to clean up Sungai Rui By IVAN LOH [email protected] PLANTS may hold the key to helping clean up low levels of arsenic pollution in Sungai iSSBl, .a»™.™ Rui, Hulu Perak. f-gp I ffgsggg A discussion is now ongoing between the is3s*i»3ill Perak Forestry Department and Forest Research Institute Malaysia (FRIM) to search for plants that can absorb pollution. Perak Mentri Besar Datuk Seri Ahmad Faizal Azumu said the task force that was set up to look into the polluted river issue had recommended the move in its bid to clean up the river. He said it was one of its suggestions to rehabilitate idle mining areas near the river. "We will execute it once the species of plant have been identified. Recent checks showed low levels of arsenic in Sungai Rui. Villagers along the river have complained about skin problems which they believe "For now, the state Department of are linked to the river contamination. (Right) Ahmad Faizal says the state Department of Environment will continue to monitor the situation Environment will continue to monitor the at Sungai Rui. situation there," he said during a press con- ference at the state secretariat building. samples from 300 people near Kampung "The task force will be informed of any further drop in river water quality," he "The presence of arsenic in tfie river may added. -

Politik Dimalaysia Cidaip Banyak, Dan Disini Sangkat Empat Partai Politik

122 mUah Vol. 1, No.I Agustus 2001 POLITICO-ISLAMIC ISSUES IN MALAYSIA IN 1999 By;Ibrahim Abu Bakar Abstrak Tulisan ini merupakan kajian singkat seJdtar isu politik Islam di Malaysia tahun 1999. Pada Nopember 1999, Malaysia menyelenggarakan pemilihan Federal dan Negara Bagian yang ke-10. Titik berat tulisan ini ada pada beberapa isupolitik Islamyang dipublikasikandi koran-koran Malaysia yang dilihat dari perspektifpartai-partaipolitik serta para pendukmgnya. Partai politik diMalaysia cidaip banyak, dan disini Sangkat empat partai politik yaitu: Organisasi Nasional Malaysia Bersatu (UMNO), Asosiasi Cina Ma laysia (MCA), Partai Islam Se-Malaysia (PMIP atau PAS) dan Partai Aksi Demokratis (DAP). UMNO dan MCA adalah partai yang berperan dalam Barisan Nasional (BA) atau FromNasional (NF). PASdan DAP adalah partai oposisipadaBarisanAltematif(BA) atau FromAltemattf(AF). PAS, UMNO, DAP dan MCA memilikipandangan tersendiri temang isu-isu politik Islam. Adanya isu-isu politik Islam itu pada dasamya tidak bisa dilepaskan dari latar belakang sosio-religius dan historis politik masyarakat Malaysia. ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^^ ^ <•'«oJla 1^*- 4 ^ AjtLtiLl jS"y Smi]?jJI 1.^1 j yLl J J ,5j^I 'jiil tJ Vjillli J 01^. -71 i- -L-Jl cyUiLLl ^ JS3 i^LwSr1/i VjJ V^j' 0' V oljjlj-l PoUtico-Islnndc Issues bi Malays bi 1999 123 A. Preface This paper is a short discussion on politico-Islamic issues in Malaysia in 1999. In November 1999 Malaysia held her tenth federal and state elections. The paper focuses on some of the politico-Islamic issues which were pub lished in the Malaysian newsp^>ers from the perspectives of the political parties and their leaders or supporters. -

Majlis Gerakan Negara (MAGERAN): Usaha Memulihkan Semula Keamanan Negara Malaysia

170 Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH), Volume 5, Issue 12, (page 170 - 178), 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.47405/mjssh.v5i12.585 Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH) Volume 5, Issue 12, December 2020 e-ISSN : 2504-8562 Journal home page: www.msocialsciences.com Majlis Gerakan Negara (MAGERAN): Usaha Memulihkan Semula Keamanan Negara Malaysia Mohd Sohaimi Esa1, Romzi Ationg1 1Pusat Penataran Ilmu dan Bahasa, Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS) Correspondence: Mohd Sohaimi Esa ([email protected]) Abstrak ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ Susulan peristiwa 13 Mei 1969, sehari kemudian kerajaan telah mengisytiharkan Darurat di seluruh negara. Sehubungan itu, bagi memulihkan keamanan, kerajaan telah menubuhkan Majlis Gerakan Negara (MAGERAN) pada 16 Mei 1969. Pada umumnya, keanggotaan jawatankuasa dan matlamat MAGERAN telah banyak dibincangkan dalam mana-mana penulisan. Namun begitu, persoalan bagaimanakah pemimpin utama dalam MAGERAN dipilih masih belum begitu jelas dibincangkan lagi. Justeru itu, dengan berasaskan kaedah disiplin sejarah perkara ini akan dirungkaikan dalam artikel ini. Artikel ini juga akan membincangkan langkah-langkah yang telah diambil oleh MAGERAN untuk memulihkan semula keamanan dan sistem demokrasi yang telah lama diamalkan di negara ini. Dalam pada itu, kertas kerja ini menegaskan bahawa dengan adanya kepimpinan yang berwibawa dalam MAGERAN maka keamanan negara telah berjaya dipulihkan dalam masa yang -

1988 Crisis: Salleh Shot Himself in the Foot? Malaysiakini.Com Apr 23, 2008 P Suppiah

1988 crisis: Salleh shot himself in the foot? Malaysiakini.com Apr 23, 2008 P Suppiah The personalities involved in the entire episode are as follows: * The then Yang Di Pertuan Agong (the King), now the Sultan of Johor * Tun Salleh Abas, who was then the Lord President * The prime minister (Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, who was then Datuk Seri Dr), * The then attorney-general, Tan Sri Abu Talib Othman, now Suhakam chief. The whole episode started with Salleh writing a letter to the King dated March 26, 1988, copies of which were sent to the Malay rulers. On May 27, 1988 the prime minister in the presence of high-ranking government officials informed Salleh that the King wished him to step down (to retire as Lord President) because of the said letter. Salleh on May 28, 1988 sent a letter of resignation: the next day he withdrew it and subsequently held a press conference. On June 9, 1988 the prime minister made a second representation to the King alleging further misconduct on the part of Salleh based on his undignified use of the press to vent his grievances – such as requesting for a public hearing of the tribunal and asking for persons of high judicial standing to sit on the tribunal. On June 11, 1988, members of the tribunal were appointed pursuant to the Federal Constitution by the King. On June 14, 1988, Salleh was served with the list of charges against him. On June 17, 1988, Salleh was served with a set of rules to govern the tribunal procedure. -

Ong Boon Hua @ Chin Peng & Anor V. Menteri Hal Ehwal Dalam Negri

The Malaysian Bar Ong Boon Hua @ Chin Peng & Anor v. Menteri Hal Ehwal Dalam Negri, Malaysia & Ors 2008 [CA] Friday, 20 June 2008 09:11PM ONG BOON HUA @ CHIN PENG & ANOR V. MENTERI HAL EHWAL DALAM NEGERI, MALAYSIA & ORS COURT OF APPEAL, PUTRAJAYA [CIVIL APPEAL NO: W-01-87-2007] LOW HOP BING JCA; ABDUL MALIK ISHAK JCA; SULAIMAN DAUD JCA 15 MAY 2008 JUDGMENT Abdul Malik Ishak JCA: The Background Facts 1. Cessation of armed activities between the Government of Malaysia and the Communist Party of Malaya was a welcome news for all Malaysians. It became a reality on 2 December 1989. On that date, an agreement was entered between the Government of Malaysia (the fourth respondent/defendant) and the Communist Party of Malaya (the second appellant/applicant) to terminate armed hostilities between the parties (hereinafter referred to as the "agreement"). With the signing of the agreement, armed hostilities between the parties ended and peace prevailed. The terms of the agreement can be seen at p. 235 of the appeal record at Jilid 1 (hereinafter referred to as "ARJ1"). There were four articles to that agreement and the relevant ones read as follows: Article 3 - Residence In Malaysia 3.1 Members of the Communist Party of Malaya and members of its disbanded armed units, who are of Malaysian origin and who wish to settle down in Malaysia, shall be allowed to do so in accordance with the laws of Malaysia. 3.2 Members of the Communist Party of Malaya and members of its disbanded armed units, who are not of Malaysian origin, may be allowed to settle down in MALAYSIA in accordance with the laws of MALAYSIA, if they so desire. -

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ISSN 0219-3213 TRS15/21s ISSUE ISBN 978-981-5011-00-5 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace 15 Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 5 0 1 1 0 0 5 2021 21-J07781 00 Trends_2021-15 cover.indd 1 8/7/21 12:26 PM TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 1 9/7/21 8:37 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Singapore APEC Study Centre and the Temasek History Research Centre (THRC). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 2 9/7/21 8:37 AM THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik ISSUE 15 2021 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 3 9/7/21 8:37 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2021 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

Penyata Rasmi Official Report

Jilid III Bari Khamil Bil. 2 19hb April, 1973 MALAYSIA PENYATA RASMI OFFICIAL REPORT DEWAN RAKYAT HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES PARLIMEN KETIGA Third Parliament PENGGAL PARLIMEN KETIGA Third Session KANDUNGANNYA JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN MULUT BAGI PERTANYAAN•PERTANYAAN [Ruangan f.63] RANG UNDANG-UNDANG DI BAWA KE DALAM MESYUARAT [Ruangan 201) PINDAAN KEPADA USUL UCAPAN TERIMA KASm-PARTI PEM BANGKANG [Ruangan 203) USUL: Ucapan Terima KMih kepada D.Y.M.M. Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Agong [Ruangan 203] DICETAK OLEH MOHD. DAUD BIN ABDUL RAHMAN, KETUA PENGARAH PERCETAKAN KUALA LUMPUR 1973 MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT YANG KETIGA Penyata Rasmi PENGGAL YANG KETIGA Hari K.hamis, l 9hb April, 1973 Mesyuarat dimulakan pada puku/ 2.30 petang YANG HADIR: Yang Berhormat Tuan Yang di Pertua, Tan Sri DATUK CHIK MOHAMED YUSUF BIN SHEIKH ABDUL RAHMAN, P.M.N., s.P.M.P., J.P., Datuk Bendahara Perak. Yang Amat Berhormat Timbalan Perdana Menteri, Menteri Hal Ehwal Dalam Negeri dan Menteri Perdagangan dan Perindastrian, TuN DR ISMAIL AL-HAJ BIN DATUK HAJI ABDUL RAHMAN, S.S.M. P.M.N., S.P.M.J. (Johor Timor). Yang Berhormat Menteri Perhubungan, TAN SRI HAJI SARDON BIN HAJI JUBIR, P.M.N., S.P.M.K. S.P.M.J. (Pontian Utara). Menteri Hal Ehwal Sarawak, TAN SRI ThMENGGONG JUGAH ANAK " BARIENG, P.M.N., P.D.K., P.N.B.s., o.B.E., Q.M.c. (Ulu Rajang). Menteri Buruh dan Tenaga Rakyat, TAN SRI V. MANICKAVASAGAM, " P.M.N., S.P.M.S., J.M.N., P.J.K. (Kelang). Menteri Pembangunan Negara dan Luar Bandar, TuAN ABDUL GHAFAR " BIN BABA (Melaka Utara). -

9789814841450

TIM DONOGHUE Karpal Singh, a tetraplegic following a road accident in Penang in 2005, literally ‘died in the saddle’ when For Review only his specially modified Toyota Alphard crashed into the back of a lorry on the North-South highway KARPAL in the early hours of 17 April 2014. He was widely regarded as the best criminal and constitutional lawyer practising in Malaysia when he lost the game of chance everyone plays when they venture out TIM DONOGHUE is a journalist based SINGH KARPAL onto a Malaysian road. in New Zealand. He has been a frequent visitor KARPAL SINGH SINGH One of Karpal’s biggest achievements was his to Malaysia since 1986, and on his last trip in TIGER OF JELUTONG TIGER OF JELUTONG steely defence of Malaysia’s former Deputy Prime TIGER OF JELU April 2014 bade farewell to Karpal Singh at the THE FULL BIOGRAPHY Minister Anwar Ibrahim on two charges of sodomy Sikh Temple in Penang. There, in the company With a New Foreword by Gobind Singh Deo and one of corruption. Many in the international of thousands of Punjabi people from throughout community, including members of the Inter- Malaysia, he reflected on the life of an incorrigible The full biography of Malaysia’s fearless Parliamentary Union, believe the charges against legal and political warrior during three days criminal and constitutional lawyer and human rights Anwar were politically motivated and designed to of prayer. advocate by veteran journalist Tim Donoghue prevent him from leading an opposition coalition to victory in the next two general elections. At the time Donoghue first met Karpal in early 1987 while of Karpal’s death, Anwar had been sentenced to five based in Hong Kong as the New Zealand Press “Tim Donoghue’s well-written biography of Karpal Singh .. -

Federalisme Dan Pengurusan Pendidikan Islam Di Kelantan

Kajian Malaysia, Vol. 36, No. 2, 2018, 89–111 FEDERALISME DAN PENGURUSAN PENDIDIKAN ISLAM DI KELANTAN FEDERALISM AND MANAGEMENT OF ISLAMIC EDUCATION IN KELANTAN Azmil Mohd Tayeb1* and Sharifah Nursyahidah Syed Annuar2 1School of Social Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Pulau Pinang, MALAYSIA 2Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Selangor, MALAYSIA *Corresponding author: [email protected] Published online: 28 September 2018 To cite this article: Azmil Mohd Tayeb and Sharifah Nursyahidah Syed Annuar. 2018. Federalisme dan pengurusan pendidikan Islam di Kelantan. Kajian Malaysia 36(2): 89–111. https://doi.org/ 10.21315/km2018.36.2.5 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.21315/km2018.36.2.5 ABSTRAK Secara teorinya, federalisme sebagai sebuah sistem tadbir urus membolehkan susunan kuasa yang seimbang antara kerajaan persekutuan dengan negeri-negeri komponen yang berautonomi, yang secara rasmi digariskan oleh perlembagaan. Walau bagaimanapun, dalam amalan yang sebenar, keseimbangan kuasa itu jarang berlaku. Di Malaysia, sistem persekutuan amat memihak kepada kerajaan persekutuan yang dominan walaupun bidang kuasa yang jelas telah diberikan kepada negeri-negeri oleh perlembagaan. Artikel ini akan menggambarkan mengapa kerajaan persekutuan di Malaysia dapat mengatasi pemisahan kuasa yang dibentuk secara perlembagaan dengan menumpukan kepada bidang pendidikan Islam. Jadual Kesembilan dan Artikel 3 Perlembagaan Malaysia menetapkan bahawa setiap negeri mempunyai kuasa yang meluas untuk mentadbir hal ehwal Melayu dan Islam dalam batasnya sendiri, di mana pendidikan Islam adalah sebahagian daripadanya, dengan campur tangan yang minimum daripada kerajaan persekutuan. Pada hakikatnya, sejak akhir tahun The original article in English was published as "Federalism in Serambi Mekah: Islamic Education in Kelantan," in Illusions of Democracy: Malaysian Politics and People Volume II, ed.