Download Gothic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: the Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry Versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 5 Issue 2 135-172 2015 The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry Nelly Shafik Ramzy Sinai University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Ramzy, Nelly Shafik. "The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5, 2 (2015): 135-172. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol5/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ramzy The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry By Nelly Shafik Ramzy, Department of Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, Sinai University, El Masaeed, El Arish City, Egypt 1. Introduction When performing geometrical analysis of historical buildings, it is important to keep in mind what were the intentions -

Laon Cathedral • Early Gothic Example with a Plan That Resembles Romanesque

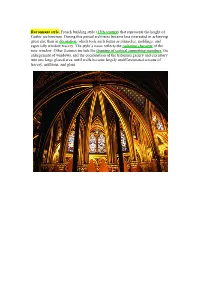

Gothic Art • The Gothic period dates from the 12th and 13th century. • The term Gothic was a negative term first used by historians because it was believed that the barbaric Goths were responsible for the style of this period. Gothic Architecture The Gothic period began with the construction of the choir at St. Denis by the Abbot Suger. • Pointed arch allowed for added height. • Ribbed vaulting added skeletal structure and allowed for the use of larger stained glass windows. • The exterior walls are no longer so thick and massive. Terms: • Pointed Arches • Ribbed Vaulting • Flying Buttresses • Rose Windows Video - Birth of the Gothic: Abbot Suger and St. Denis Laon Cathedral • Early Gothic example with a plan that resembles Romanesque. • The interior goes from three to four levels. • The stone portals seem to jut forward from the façade. • Added stone pierced by arcades and arched and rose windows. • Filigree-like bell towers. Interior of Laon Cathedral, view facing east (begun c. 1190 CE). Exterior of Laon Cathedral, west facade (begun c. 1190 CE). Chartres Cathedral • Generally considered to be the first High Gothic church. • The three-part wall structure allowed for large clerestory and stained-glass windows. • New developments in the flying buttresses. • In the High Gothic period, there is a change from square to the new rectangular bay system. Khan Academy Video: Chartres West Facade of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). Royal Portals of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). Nave, Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). -

Catalonia 1400 the International Gothic Style

Lluís Borrassà: the Vocation of Saint Peter, a panel from the Retable of Saint Peter in Terrassa Catalonia 1400 The International Gothic Style Organised by: Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya. From 29 March to 15 July 2012 (Temporary Exhibitions Room 1) Curator: Rafael Cornudella (head of the MNAC's Department of Gothic Art), with the collaboration of Guadaira Macías and Cèsar Favà Catalonia 1400. The International Gothic Style looks at one of the most creative cycles in the history of Catalan art, which coincided with the period in western art known as the 'International Gothic Style'. This period, which began at the end of the 14th century and went on until the mid-15th century, gave us artists who played a central role in the history of European art, as in the case of Lluís Borrassà, Rafael Destorrents, Pere Joan and Bernat Martorell. During the course of the 14th century a process of dialogue and synthesis took place between the two great poles of modernity in art: on one hand Paris, the north of France and the old Netherlands, and on the other central Italy, mainly Tuscany. Around 1400 this process crystallised in a new aesthetic code which, despite having been formulated first and foremost in a French and 'Franco- Flemish' ambit, was also fed by other international contributions and immediately spread across Europe. The artistic dynamism of the Franco- Flemish area, along with the policies of patronage and prestige of the French ruling House of Valois, explain the success of a cultural model that was to captivate many other European princes and lords. -

Pages 114- 129 Great Architecture of the World Readings

Readings Pages 114- 129 Great Architecture of the World ARCH 1121 HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURAL TECHNOLOGY Photo: Alexander Aptekar © 2009 Gothic Architecture 1140-1500 Influenced by Romanesque Architecture While Romanesque remained solid and massive – Gothic: 1) opened up to walls with enormous windows and 2) replaced semicircular arch with the pointed arch. Style emerged in France Support: Piers and Flying Buttresses Décor: Sculpture and stained glass Effect: Soaring, vertical and skeleton-like Inspiration: Heavenly light Goal: To lift our everyday life up to the heavens Gothic Architecture 1140-1500 Dominant Art during this time was Architecture Growth of towns – more prosperous They wanted their own churches – Symbol of civic Pride More confident and optimistic Appreciation of Nature Church/Cathedral was the outlet for creativity Few people could read and write Clergy directed the operations of new churches- built by laymen Gothic Architecture 1140-1420 Began soon after the first Crusaders returned from Constantinople Brought new technology: Winches to hoist heavy stones New Translation of Euclid’s Elements – Geometry Gothic Architecture was the integration of Structure and Ornament – Interior Unity Elaborate Entrances covered with Sculpture and pronounced vertical emphasis, thin walls pierced by stained-glass Gothic Architecture Characteristics: Emphasis on verticality Skeletal Stone Structure Great Showing of Glass: Containers of light Sharply pointed Spires Clustered Columns Flying Buttresses Pointed Arches Ogive Shape Ribbed Vaults Inventive Sculpture Detail Sharply Pointed Spires Gothic Architecture 1140-1500 Abbot Suger had the vision that started Gothic Architecture Enlargement due to crowded churches, and larger windows Imagined the interior without partitions, flowing free Used of the Pointed Arch and Rib Vault St. -

Circle Patterns in Gothic Architecture

Bridges 2012: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture Circle patterns in Gothic architecture Tiffany C. Inglis and Craig S. Kaplan David R. Cheriton School of Computer Science University of Waterloo [email protected] Abstract Inspired by Gothic-influenced architectural styles, we analyze some of the circle patterns found in rose windows and semi-circular arches. We introduce a recursive circular ring structure that can be represented using a set-like notation, and determine which structures satisfy a set of tangency requirements. To fill in the gaps between tangent circles, we add Appollonian circles to each triplet of pairwise tangent circles. These ring structures provide the underlying structure for many designs, including rose windows, Celtic knots and spirals, and Islamic star patterns. 1 Introduction Gothic architecture, a style of architecture seen in many great cathedrals and castles, developed in France in the late medieval period [1, 3]. This majestic style is often applied to ecclesiastical buildings to emphasize their grandeur and solemnity. Two key features of Gothic architecture are height and light. Gothic buildings are usually taller than they are wide, and the verticality is further emphasized through towers, pointed arches, and columns. In cathedrals, the walls are often lined with large stained glass windows to introduce light and colour into the buildings. In the mid-18th century, an architectural movement known as Gothic Revival began in England and quickly spread throughout Europe. The Neo-Manueline, or Portuguese Final Gothic, developed under the influence of traditional Gothic architecture and the Spanish Plateresque style [10]. The Palace Hotel of Bussaco, designed by Italian architect Luigi Manini and built between 1888 and 1907, is a well-known example of Neo-Manueline architecture (Figure 2). -

The Romantic Movement on European Arts: a Brief Tutorial Review

SCIENTIFIC CULTURE, Vol. 1, No 2, (2015), pp. 39-46 Copyright © 2015 SC Open Access. Printed in Greece. All Rights Reserved. The Romantic Movement on European arts: a brief tutorial review Anna Lazarou Academy of Athens, 84 Solonos Str., Athens 10680, Greece ([email protected]; [email protected]) Received: 10/01/2015 Accepted: 25/02/2015 ABSTRACT The movement of romanticism in art (18th-19th c) is briefly reviewed. This artistic movement institutionalized freedom of personal expression of the artist and presented various art styles, which were rooted mainly in topics of the past. One of the manifestations of the romantic spirit was Neoclassicism which was based on copies of works of Greek and Roman antiquities. Romantic painters, musicians and architects have left as heritage an amazing wealth of art works. KEYWORDS: art, architecture, music, romance, artistic movement, neoclassicism. 40 Anna Lazarou 1. INTRODUCTION his vision was a European empire with its capital The period from the second half of the 18th century Paris. The economic downturn that led to wars and until the first half of the 19th century in western social changes created by the Industrial Revolution, Europe was of a multidimensional character both in made Europeans to feel trapped by events that ex- art and in other fields of intellectual life, expressed ceeded the control, which could not be explained by by the romance, the first great movement of ideas of rational perception. Even Napoleon's career was for that era e.g. architecture, music, literature (Blayney many a supernatural power and his defeat, a divine judgment (Fig.1). -

2-A-07-10-Not13-Instructions- Build a Cathedral-HS.Docx

ART 2-07 lnstructions to Build Your Cathedral 1. Print out all six pages on cardstock. 2. Cut out on all solid lines. Dotted lines are fold lines. 3. Page one: The Crossing. This should look familiar. We used it on the squinches and pendentive lesson. a. Cut down the center of the paper, to separate the pointed pieces (piece A) from the large piece (piece B) that has four folds. b. Take piece A and carefully cut all the dark areas away. Throw these dark pieces away. c. Glue section C under section D. C and D are parts of a point. When glued they make a whole point. d. Glue or tape the fold down areas of the dome. There are two ways to do this. i. First way: start on the C/D point and put a very tiny bit of glue on the back of the fold down section. Then bring point E over to the C/D point. C/D should be under the E point. Continue putting glue on the back of the glued down section and bringing the next point over. You may have overlap. That is okay. Just glue all the points to the center. ii. Second way: put tape on the inside of the C/D point and then bring all the points up and stick to the tape. e. The four triangles on the bottom of the dome are the squinches or pendentives. Fold them out. Carefully crease this fold. f. Set dome aside. Piece B is the nave. This is where the people sit. -

Rayonnant Style, French Building Style (13Th Century) That Represents the Height of Gothic Architecture

Rayonnant style, French building style (13th century) that represents the height of Gothic architecture. During this period architects became less interested in achieving great size than in decoration, which took such forms as pinnacles, moldings, and especially window tracery. The style’s name reflects the radiating character of the rose window. Other features include the thinning of vertical supporting members, the enlargement of windows, and the combination of the triforium gallery and clerestory into one large glazed area, until walls became largely undifferentiated screens of tracery, mullions, and glass. Flamboyant style, phase of late Gothic architecture in 15th-century France and Spain. It evolved out of the Rayonnant style’s increasing emphasis on decoration. Its most conspicuous feature is the dominance in stone window tracery of a flamelike S- shaped curve. Wall surface was reduced to the minimum to allow an almost continuous window expanse. Structural logic was obscured by covering buildings with elaborate tracery. Flamboyant Gothic, which became increasingly ornate, gave way in France to Renaissance forms in the 16th century. Perpendicular style, Phase of late Gothic architecture in England roughly parallel in time to the French Flamboyant style. The style, concerned with creating rich visual effects through decoration, was characterized by a predominance of vertical lines in stone window tracery, enlargement of windows to great proportions, and conversion of the interior stories into a single unified vertical expanse. Fan vaults, springing from slender columns or pendants, became popular. In the 16th century, the grafting of Renaissance elements onto the Perpendicular style resulted in the Tudor style. Manueline, Portuguese Manuelino, particularly rich and lavish style of architectural ornamentation indigenous to Portugal in the early 16th century. -

Rose Window Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Rose Window from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

6/19/2016 Rose window Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Rose window From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A rose window or Catherine window is often used as a generic term applied to a circular window, but is especially used for those found in churches of the Gothic architectural style and being divided into segments by stone mullions and tracery. The name “rose window” was not used before the 17th century and according to the Oxford English Dictionary, among other authorities, comes from the English flower name rose.[1] The term “wheel window” is often applied to a window divided by simple spokes radiating from a central boss or opening, while the term “rose window” is reserved for those windows, sometimes of a highly complex design, which can be seen to bear similarity to a multipetalled rose. Rose windows are also called Catherine windows after Saint Catherine of Alexandria who was sentenced to be executed on a spiked wheel. A circular Exterior of the rose at Strasbourg window without tracery such as are found in many Italian churches, is Cathedral, France. referred to as an ocular window or oculus. Rose windows are particularly characteristic of Gothic architecture and may be seen in all the major Gothic Cathedrals of Northern France. Their origins are much earlier and rose windows may be seen in various forms throughout the Medieval period. Their popularity was revived, with other medieval features, during the Gothic revival of the 19th century so that they are seen in Christian churches all over the world. Contents 1 History 1.1 Origin 1.2 The windows of Oviedo Interior of the rose at Strasbourg 1.3 Romanesque circular windows Cathedral. -

EARLY NETHERLANDISH PAINTING Part One

EARLY NETHERLANDISH PAINTING part one Early Netherlandish painting is the work of artists, sometimes known as the Flemish Primitives, active in the Burgundian and Habsburg Netherlands during the 15th- and 16th-century Northern Renaissance, especially in the flourishing cities of Bruges, Ghent, Mechelen, Leuven, Tounai and Brussels, all in present-day Belgium. The period begins approximately with Robert Campin and Jan van Eyck in the 1420s and lasts at least until the death of Gerard David in 1523, although many scholars extend it to the start of the Dutch Revolt in 1566 or 1568. Early Netherlandish painting coincides with the Early and High Italian Renaissance but the early period (until about 1500) is seen as an independent artistic evolution, separate from the Renaissance humanism that characterised developments in Italy; although beginning in the 1490s as increasing numbers of Netherlandish and other Northern painters traveled to Italy, Renaissance ideals and painting styles were incorporated into northern painting. As a result, Early Netherlandish painters are often categorised as belonging to both the Northern Renaissance and the Late or International Gothic. Robert Campin (c. 1375 – 1444), now usually identified with the Master of Flémalle (earlier the Master of the Merode Triptych), was the first great master of Flemish and Early Netherlandish painting. Campin's identity and the attribution of the paintings in both the "Campin" and "Master of Flémalle" groupings have been a matter of controversy for decades. Campin was highly successful during his lifetime, and thus his activities are relatively well documented, but he did not sign or date his works, and none can be confidently connected with him. -

Dana Jenei, Gothic in Transylvania. the Painting (C

Book Reviews / Buchrezensionen Dana Jenei, Gothic in Transylvania. The Painting (c. 1300-1500), Oscar Print Publishing House, București, 2016, 240 p., 156 il., with a foreword by Răzvan Theodorescu Adrian Stoia* As the author has already accustomed us with her previous works, this new volume is printed in exquisite graphical conditions. The book presents two centuries of Western painting created in Tran- sylvania, an area situated at the border of Western European culture. More precisely, it refers to the flourishing period of the Gothic art, stimulated by the development of urban and rural communities invited here by the Hun- garian crown, until the political and religious changes caused by the fall of the Hungarian Kingdom under the Turks and the dawn of the Reformation, when numerous works of the Catholic art were destroyed. As the author states, the book presents the research “started in faculty and first materialized in the PhD thesis”, defended in 2005 at the National University of Arts in Bucharest, with the scientific information updated to 2016, and “presented in the spirit of the «new manner of writing history» of the French School of Les Annales” (pp. 10-11). The volume opens with a brief analysis of the state of research in the field (pp. 11-13), continued by the chapterTransylvania in late Middle Ages (pp. 14-26), divided into four parts: Historical sketch, The crisis of „the security symbols”, New religious sensitivity and Care for life after death. Here are men- tioned the anxieties of the Transylvanian society – the war, the famine and the plague”– the permanent Ottoman menace, the economic, medical and climate problems that Medieval Europe has faced. -

ART-102 History of Art and Visual Culture to 1400

Bergen Community College Division of Arts and Humanities Department of Arts & Communication Course Syllabus Art 102 History of Art and Visual Culture to 1400 Three Credits - Three Hours I. Catalogue Description: History of Art and Visual Culture to 1400 is a chronological survey of art and visual culture, western and non-western, from the Mesopotamian period through the Middle Ages. In a lecture and discussion format, selected works of sculpture, architecture, and painting as well as decorative utilitarian objects made by peoples in Europe, the Middle East, India, Asia and Africa are studied both for their styles and materials and their relation to politics, religion and patronage. II. Student Learning Objectives: As a result of meeting the requirements of this course, students will be able to A. Identify major periods of art history, and exemplary works of art and visual culture, from ca. 3500 bce to ca. 1400, in western and non-western societies B. Define and use vocabulary of visual analysis in speech and writing C. Describe the materials used and the techniques employed to make works of art in a variety of media in these periods and cultures D. Describe how political, religious and economic situations influence the creation of works of art and their meaning and significance E. Analyze the difference between perceiving a work of art viewed on the internet and the same work experienced directly within a museum context. III. Course Content: A. Course Orientation 1. Procedures and requirements 2. Structure of course 3. Explanation of special features: museum visits 4. Evaluation methods B. Ancient Art 1.