The Romantic Movement on European Arts: a Brief Tutorial Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mannerist Architecture and the Baroque in This Lecture I Want To

Mannerist Architecture and the Baroque In this lecture I want to discuss briefly the nature of Mannerist architecture and then begin to consider baroque art. We have already paid some attention to Mannerist painting and sculpture; and have seen how in the work of painters like Rosso Fiorentino, Bronzino and Parmigianino; and sculptors like Giovanni Bologna and Cellini, that after 1527, classical forms came to be used in a spirit alien to them; each artist developing a highly personal style containing capricious, irrational and anti-classical effects. Although the term Mannerism was first applied to painting before it came to be used to describe the period style between 1527 and 1600; it is possible to find similar mannerist qualities in the architecture of the time. And again it is Michelangelo whose work provides, as it were, a fountainhead of the new style. Rosso’s Decent from the Cross, which we have taken as one of the first signs of Mannerist strain and tension in the High Renaissance world, was painted in 1521. Three years later Michelangelo designed his Laurentian Library,* that is in 1524. It was designed to house the library of the Medicis; and we may take it as the first important building exhibiting Mannerist features.* We can best consider these features by comparing the interior of the library with the interior of an early Renaissance building such as Brunelleschi’s S. Lorenzo. Consider his use of columns. In Brunelleschi they are free standing. When he uses pilasters they project out from a wall as you expect a buttress to. -

Catalonia 1400 the International Gothic Style

Lluís Borrassà: the Vocation of Saint Peter, a panel from the Retable of Saint Peter in Terrassa Catalonia 1400 The International Gothic Style Organised by: Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya. From 29 March to 15 July 2012 (Temporary Exhibitions Room 1) Curator: Rafael Cornudella (head of the MNAC's Department of Gothic Art), with the collaboration of Guadaira Macías and Cèsar Favà Catalonia 1400. The International Gothic Style looks at one of the most creative cycles in the history of Catalan art, which coincided with the period in western art known as the 'International Gothic Style'. This period, which began at the end of the 14th century and went on until the mid-15th century, gave us artists who played a central role in the history of European art, as in the case of Lluís Borrassà, Rafael Destorrents, Pere Joan and Bernat Martorell. During the course of the 14th century a process of dialogue and synthesis took place between the two great poles of modernity in art: on one hand Paris, the north of France and the old Netherlands, and on the other central Italy, mainly Tuscany. Around 1400 this process crystallised in a new aesthetic code which, despite having been formulated first and foremost in a French and 'Franco- Flemish' ambit, was also fed by other international contributions and immediately spread across Europe. The artistic dynamism of the Franco- Flemish area, along with the policies of patronage and prestige of the French ruling House of Valois, explain the success of a cultural model that was to captivate many other European princes and lords. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

The Baroque in Games: a Case Study of Remediation

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2020 The Baroque in Games: A Case Study of Remediation Stephanie Elaine Thornton San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Thornton, Stephanie Elaine, "The Baroque in Games: A Case Study of Remediation" (2020). Master's Theses. 5113. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.n9dx-r265 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/5113 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BAROQUE IN GAMES: A CASE STUDY OF REMEDIATION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Art History and Visual Culture San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Arts By Stephanie E. Thornton May 2020 © 2020 Stephanie E. Thornton ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled THE BAROQUE IN GAMES: A CASE STUDY OF REMEDIATION by Stephanie E. Thornton APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY AND VISUAL CULTURE SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY May 2020 Dore Bowen, Ph.D. Department of Art History and Visual Culture Anthony Raynsford, Ph.D. Department of Art History and Visual Culture Anne Simonson, Ph.D. Emerita Professor, Department of Art History and Visual Culture Christy Junkerman, Ph. D. Emerita Professor, Department of Art History and Visual Culture ABSTRACT THE BAROQUE IN GAMES: A CASE STUDY OF REMEDIATION by Stephanie E. -

Flesh As Relic: Painting Early Christian Female Martyrs Within

FLESH AS RELIC: PAINTING EARLY CHRISTIAN FEMALE MARTYRS WITHIN BAROQUE SACRED SPACES by Stormy Lee DuBois A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art in Art History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana November 2019 ©COPYRIGHT by Stormy Lee DuBois 2019 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to offer my sincerest gratitude to my committee, Dr. Todd Larkin, Dr. Regina Gee, and Dr. Melissa Ragain, for supporting me throughout my coursework at Montana State University and facilitating both graduate research and pedagogical inspiration during the study abroad program in Italy. I would also like to thank School of Art Director, Vaughan Judge for his continued support of art historical research and for the opportunities the program has afforded me. My thanks also go my husband, Josh Lever for his love and support. Thanks are also in order to Dani Huvaere for reading every draft and considering every possibility. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 2. BAROQUE PAINTING CONVENTIONS: STYLISTIC INTERPRETATIONS OF TRIDENTINE REQUIREMENTS FOR RELIGIOUS ART ............................................................................................... 4 Baroque Classicism and Naturalism ............................................................................. 4 Burial of Saint Lucy.................................................................................................. -

EARLY NETHERLANDISH PAINTING Part One

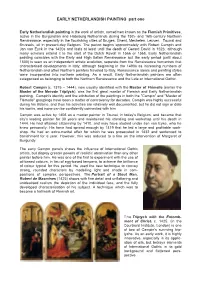

EARLY NETHERLANDISH PAINTING part one Early Netherlandish painting is the work of artists, sometimes known as the Flemish Primitives, active in the Burgundian and Habsburg Netherlands during the 15th- and 16th-century Northern Renaissance, especially in the flourishing cities of Bruges, Ghent, Mechelen, Leuven, Tounai and Brussels, all in present-day Belgium. The period begins approximately with Robert Campin and Jan van Eyck in the 1420s and lasts at least until the death of Gerard David in 1523, although many scholars extend it to the start of the Dutch Revolt in 1566 or 1568. Early Netherlandish painting coincides with the Early and High Italian Renaissance but the early period (until about 1500) is seen as an independent artistic evolution, separate from the Renaissance humanism that characterised developments in Italy; although beginning in the 1490s as increasing numbers of Netherlandish and other Northern painters traveled to Italy, Renaissance ideals and painting styles were incorporated into northern painting. As a result, Early Netherlandish painters are often categorised as belonging to both the Northern Renaissance and the Late or International Gothic. Robert Campin (c. 1375 – 1444), now usually identified with the Master of Flémalle (earlier the Master of the Merode Triptych), was the first great master of Flemish and Early Netherlandish painting. Campin's identity and the attribution of the paintings in both the "Campin" and "Master of Flémalle" groupings have been a matter of controversy for decades. Campin was highly successful during his lifetime, and thus his activities are relatively well documented, but he did not sign or date his works, and none can be confidently connected with him. -

The Utrecht Caravaggisti the Painter of This Picture, Jan Van Bijlert, Was Born in Utrecht in the Netherlands, a City Today Stil

The Utrecht Caravaggisti The painter of this picture, Jan van Bijlert, was born in Utrecht in the Netherlands, a city today still known for its medieval centre and home to several prominent art museums. In his beginnings, Jan van Bijlert became a student of Dutch painter Abraham Bloemaert. He later spent some time travelling in France as well as spending the early 1620s in Rome, where he was influenced by the Italian painter Caravaggio. This brings us on to the Caravaggisti, stylistic followers of this late 16th-century Italian Baroque painter. Caravaggio’s influence on the new Baroque style that eventually emerged from Mannerism was profound. Jan van Bijlert had embraced his style totally before returning home to Utrecht as a confirmed Caravaggist in roughly 1645. Caravaggio tended to differ from the rest of his contemporaries, going about his life and career without establishing as much as a studio, nor did he try to set out his underlying philosophical approach to art, leaving art historians to deduce what information they could from his surviving works alone. Another factor which sets him apart from his contemporaries is the fact that he was renowned during his lifetime although forgotten almost immediately after his death. Many of his works were released into the hands of his followers, the Caravaggisti. His relevance and major role in developing Western art was noticed at quite a later time when rediscovered and was ‘placed’ in the European tradition by Roberto Longhi. His importance was quoted as such, "Ribera, Vermeer, La Tour and Rembrandt could never have existed without him. -

Spanish Art (Renaissance and Baroque)

Centro de Lenguas Modernas – Universidad de Granada – Syllabus Hispanic Studies SPANISH ART (RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE) General description This subject deals with the study of the forms of artistic expression in Spain between the 16th and end of the 18th centuries, in two differentiated blocks: Renaissance Art and Baroque Art. The analysis of these two blocks explains the main lines of artistic expression of the period and their evolution, giving attention – for reasons of brevity – to the principal figures of each epoch. The specific aims of the subject are, on the one hand, to understand the essential trends of Spanish artistic expression of the Modern Age, integrating them in their historical, social and ideological context; on the other hand, to develop the linguistic competence of the student in the Spanish language. Content I. INTRODUCTION TO ARTISTIC VOCABULARY 1. Architecture, sculpture and painting terms. II. RENAISSANCE SPANISH ART 2. SPAIN OF THE 16TH CENTURY: POLITICAL AND CULTURAL EVOLUTION. From Hispanic unity to Empire. Artistic patronage as social representation. From the Flemish tradition to Italian novelty. 3. SPANISH ARCHITECTURE OF THE RENAISSANCE The slow introduction of the Renaissance: first examples. Imperial architecture and classicism. State architecture: the Escorial. 4.SPANISH SCULPTURE OF THE 16TH CENTURY Italian artists in Spain and Spanish in Italy. The mannerism of Berruguete. Sculpture in the court of Philip II and Romanism: the Leoni and Gaspar Becerra. 5.SPANISH PAINTING IN THE 16TH CENTURY Influence of Leonardo and Rafael: Valencian painting. Castilian mannerism. Painting in the Philippine court. The subjective option of El Greco. III. SPANISH BAROQUE ART 6.THE SOCIOCULTURAL CONTEXT OF BAROQUE SPAIN Spain of the 17th and 18th centuries. -

Original Neurology and Medicine in Baroque Painting

Original Neurosciences and History 2017; 5(1): 26-37 Neurology and medicine in Baroque painting L. C. Álvaro Department of Neurology, Hospital de Basurto. Bilbao, Spain. Department of Neurosciences, Universidad del País Vasco. Leoia, Spain. ABSTRACT Introduction. Paintings constitute a historical source that portays medical and neurological disorders. e Baroque period is especially fruitful in this respect, due to the pioneering use of faithful, veristic representation of natural models. For these reasons, this study will apply a neurological and historical perspective to that period. Methods. We studied Baroque paintings from the Prado Museum in Madrid, the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, and the catalogues from exhibitions at the Prado Museum of the work of Georges de La Tour (2016) and Ribera (Pinturas [Paintings], 1992; and Dibujos [Drawings], 2016). Results. In the work of Georges de La Tour, evidence was found of focal dystonia and Meige syndrome ( e musicians’ brawl and Hurdy-gurdy player with hat), as well as de ciency diseases (pellagra and blindness in e pea eaters, anasarca in e ea catcher). Ribera’s paintings portray spastic hemiparesis in e clubfoot, and a complex endocrine disorder in the powerfully human Magdalena Ventura with he r husband and son. His drawings depict physical and emotional pain; grotesque deformities; allegorical gures with facial deformities representing moral values; and drawings of documentary interest for health researchers. Finally, Juan Bautista Maíno’s depiction of Saint Agabus sho ws cervical dystonia, reinforcing the compassionate appearance of the monk. Conclusions. e naturalism that can be seen in Baroque painting has enabled us to identify a range of medical and neurological disorders in the images analysed. -

1 Caravaggio and a Neuroarthistory Of

CARAVAGGIO AND A NEUROARTHISTORY OF ENGAGEMENT Kajsa Berg A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia September 2009 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on the condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior written consent. 1 Abstract ABSTRACT John Onians, David Freedberg and Norman Bryson have all suggested that neuroscience may be particularly useful in examining emotional responses to art. This thesis presents a neuroarthistorical approach to viewer engagement in order to examine Caravaggio’s paintings and the responses of early-seventeenth-century viewers in Rome. Data concerning mirror neurons suggests that people engaged empathetically with Caravaggio’s paintings because of his innovative use of movement. While spiritual exercises have been connected to Caravaggio’s interpretation of subject matter, knowledge about neural plasticity (how the brain changes as a result of experience and training), indicates that people who continually practiced these exercises would be more susceptible to emotionally engaging imagery. The thesis develops Baxandall’s concept of the ‘period eye’ in order to demonstrate that neuroscience is useful in context specific art-historical queries. Applying data concerning the ‘contextual brain’ facilitates the examination of both the cognitive skills and the emotional factors involved in viewer engagement. The skilful rendering of gestures and expressions was a part of the artist’s repertoire and Artemisia Gentileschi’s adaptation of the violent action emphasised in Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes testifies to her engagement with his painting. -

Dana Jenei, Gothic in Transylvania. the Painting (C

Book Reviews / Buchrezensionen Dana Jenei, Gothic in Transylvania. The Painting (c. 1300-1500), Oscar Print Publishing House, București, 2016, 240 p., 156 il., with a foreword by Răzvan Theodorescu Adrian Stoia* As the author has already accustomed us with her previous works, this new volume is printed in exquisite graphical conditions. The book presents two centuries of Western painting created in Tran- sylvania, an area situated at the border of Western European culture. More precisely, it refers to the flourishing period of the Gothic art, stimulated by the development of urban and rural communities invited here by the Hun- garian crown, until the political and religious changes caused by the fall of the Hungarian Kingdom under the Turks and the dawn of the Reformation, when numerous works of the Catholic art were destroyed. As the author states, the book presents the research “started in faculty and first materialized in the PhD thesis”, defended in 2005 at the National University of Arts in Bucharest, with the scientific information updated to 2016, and “presented in the spirit of the «new manner of writing history» of the French School of Les Annales” (pp. 10-11). The volume opens with a brief analysis of the state of research in the field (pp. 11-13), continued by the chapterTransylvania in late Middle Ages (pp. 14-26), divided into four parts: Historical sketch, The crisis of „the security symbols”, New religious sensitivity and Care for life after death. Here are men- tioned the anxieties of the Transylvanian society – the war, the famine and the plague”– the permanent Ottoman menace, the economic, medical and climate problems that Medieval Europe has faced. -

National Gallery of Art OPENING EXHIBITIONS CONTINUING EXHIBITIONS Film Programs Helen Frankenthaler: William M

Calendar of Events April 1993 National Gallery of Art 7:00 Concert: The Howard University Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity: 12:30 Film: The New York School APRIL Chorale, Dr. Weldon Norris, Greeks in the Land of the Nile 2:30 Gallery Talk: Between Being Conductor, Easter Concert 6:00 Films: Signs of the Times: "Big and Nothingness: Anselm Kiefer's Ben and the Jesus Picture " and "That "Zim Zum " (EB) See bottom panels for introductory 14 WEDNESDAY Little Bit Different" and foreign language tours; see 12:00 Gallery Talk: History Made 7:00 Concert: The Fiftieth American 25 SUNDAY reverse side for complete film and Recorded: Painting in Eighteenth Music Festival, National Gallery 12:00 Gallery Talk: Landscape information. Century Britain (WB) Orchestra, George Marios, Conductor Image and Idea in Lorenzo Lotto's 12:30 Film: Money Man "Allegory" (WB) 1 THURSDAY 20 TUESDAY 2:00 Gallery Talk: The Decorative 12:00 Gallery Talk: John Singleton 15 THURSDAY 12:00 Gallery Talk: French Portraits: Arts: Medieval Treasures (WB) Cop ley's "Watson and the Shark" 12:00 Gallery Talk: Introducing Art: People and Pets (EB) 4:00 Andrew W. Mellon Lecture: (WB)' Abstraction (EB) 1:00 Gallery Talk: Handle with Care: The Diffusion of Classical Art in 12:30 Film: Important Information 12:30 Film: Money Man IJorking with Objects in the National Antiquity: The Arts ofEtruria Inside: John F. Peto and the Idea of 1:00 Gallery Talk: "The Swing" by Gallery (WB) 6:00 Film: The Godless Girl Still-Life Painting Jean-Honore Fragonard (WB) 7:00 Concert: The Fiftieth American 21 WEDNESDAY Music Festival, Phyllis Bryn-Julson, 2 FRIDAY 16 FRIDAY 10:15 Special Course: The World of soprano, Donald Sutherland, piano, 12:00 Gallery Talk: "Palazzo da 12:00 Gallery Talk: Introducing Art: Rubens: Flemish Baroque Painting Rudy J rbsky, oboe Mala " by Claude Monet (WB) Portraiture (WB) 12:00 Gallery Talk: Drawings from 12:30 Film: Important Information 12:30 Film: Mow>-Man the O'Neal Collection (EB) 27 TUESDAY Inside: John F.