Trouble in Paradise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Guide to the Nonindigenous Marine Fishes of Florida

Field Guide to the Nonindigenous Marine Fishes of Florida Schofield, P. J., J. A. Morris, Jr. and L. Akins Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for their use by the United States goverment. Pamela J. Schofield, Ph.D. U.S. Geological Survey Florida Integrated Science Center 7920 NW 71st Street Gainesville, FL 32653 [email protected] James A. Morris, Jr., Ph.D. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Ocean Service National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science Center for Coastal Fisheries and Habitat Research 101 Pivers Island Road Beaufort, NC 28516 [email protected] Lad Akins Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF) 98300 Overseas Highway Key Largo, FL 33037 [email protected] Suggested Citation: Schofield, P. J., J. A. Morris, Jr. and L. Akins. 2009. Field Guide to Nonindigenous Marine Fishes of Florida. NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS 92. Field Guide to Nonindigenous Marine Fishes of Florida Pamela J. Schofield, Ph.D. James A. Morris, Jr., Ph.D. Lad Akins NOAA, National Ocean Service National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS 92. September 2009 United States Department of National Oceanic and National Ocean Service Commerce Atmospheric Administration Gary F. Locke Jane Lubchenco John H. Dunnigan Secretary Administrator Assistant Administrator Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ i Methods .....................................................................................................ii -

J. Mar. Biol. Ass. UK (1958) 37, 7°5-752

J. mar. biol. Ass. U.K. (1958) 37, 7°5-752 Printed in Great Britain OBSERVATIONS ON LUMINESCENCE IN PELAGIC ANIMALS By J. A. C. NICOL The Plymouth Laboratory (Plate I and Text-figs. 1-19) Luminescence is very common among marine animals, and many species possess highly developed photophores or light-emitting organs. It is probable, therefore, that luminescence plays an important part in the economy of their lives. A few determinations of the spectral composition and intensity of light emitted by marine animals are available (Coblentz & Hughes, 1926; Eymers & van Schouwenburg, 1937; Clarke & Backus, 1956; Kampa & Boden, 1957; Nicol, 1957b, c, 1958a, b). More data of this kind are desirable in order to estimate the visual efficiency of luminescence, distances at which luminescence can be perceived, the contribution it makes to general back• ground illumination, etc. With such information it should be possible to discuss. more profitably such biological problems as the role of luminescence in intraspecific signalling, sex recognition, swarming, and attraction or re• pulsion between species. As a contribution to this field I have measured the intensities of light emitted by some pelagic species of animals. Most of the work to be described in this paper was carried out during cruises of R. V. 'Sarsia' and RRS. 'Discovery II' (Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom and National Institute of Oceanography, respectively). Collections were made at various stations in the East Atlantic between 30° N. and 48° N. The apparatus for measuring light intensities was calibrated ashore at the Plymouth Laboratory; measurements of animal light were made at sea. -

Report on the First Scotian Shelf Ichthyoplankton Program

NOT TO BE CITED WITHOUT PRIOR REFERENCE TO THE AUTHOR (S) International Commission for a the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Serial No. 5179 ICNAF Res. Doc. 78/VI/21 (D.c.1) ANNUAl MEETING - JUNE 1978 Report on the First Scotian Shelf Ichthyoplanktoll Program (SSIP) Workshop, 29 August to 3 September 1977, St. Andrews, N. B. Sponsored by Department of Fisheries and Environment Marine Fish Division Resource Branch, Maritimes Bedford Institute of Oceanography Dartmouth, Nova Scotia TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract 2 Terms of Reference 2 Introduction 4 Oceanographic Regime •••••..••••.•.•.•••••••..••••••.••..•. 4 Overview of Present Approaches ••••••••••••••••••..•••.•••• 6 - Canada 6 - United States of America 13 - Un! ted Kingdom 19 - Federal Republic of Germany......................... 24 Sampling Recommendations 25 Sorting Protocols 26 Planning Sessions 26 Summary and Resolutions ••••••••.•..••...•••.••••...•.•.•.• 27 References 28 List of participants 30 Convener P. F. Lett Rapporteur: J. F. Schweigert C2 - 2 - ABSTRACT The Scotian Shelf ichthyoplankton workshop was organized to draw on expertise from other prevailing programs and to incorporate any new ideas on ichthyoplankton ecology and sampling 8S it might relate to the stock-recruitment problem and fisheries management. Experts from a number of leading fisheries laboratories presented overviews of their ichthyoplankton programs and approaches to fisheries management. The importance of understanding the eJirly life history of most fish species was emphasized and some pre! iminary reBul -

Freshwater Fish of New River, Belize

FRESHWATER FISH OF NEW RIVER, BELIZE Belize is home to an abundant diversity of freshwater Blue Tilapia fish species and is often considered a fisherman’s Oreochromis aureus, Tilapia paradise. The New River area is a popular freshwater Adult size: 13–20 cm (5–8 in) fishing destination in the Orange Walk district of northern Belize. Here locals and visitors alike take to the lagoons and waterways for dinner or for good sportfishing. This guide highlights the most popular species in the area and will help people identify and understand these species. A fishing license is required for all fishers, so before casting be sure to check the local laws and regulations. Tarpon Victor Atkins Megalops atlanticus This edible, fleshy fish can be identified by its overall blue Adult size: 1-2.5 m (4-8 ft) color. Adults can weigh up to 2.7kg (6 lbs). This exotic cichlid is abundant in both fresh and brackish waters. Mayan Cichlid Cichlasoma urophthalmus, Pinta Adult size: 25–27 cm (10–11 in) Albert Kok Tarpon are large fish that can weigh up to 127kg (280 lbs). They are covered in large, silver scales and have no spines in their fins, and have a broad mouth with a prominent lower jaw. Tarpon are fighters and may jump out of the water DATZ. R. Stawikowski several times when hooked. They are found in fresh and saltwater. This popular food fish has dark vertical bars and a large black eyespot with a blue border at the tail base. The first Bay Snook dorsal and anal fins have many sharp spines. -

Chelmon Rostratus (Linnaeus, 1758) Coradion Altivelis Mcculloch, 1916

click for previous page 3258 Bony Fishes Chelmon rostratus (Linnaeus, 1758) En - Copperbanded butterflyfish. Maximum total length about 20 cm. Inhabits coral reefs at depths of 3 to 20 m. Feeds on crabs, worms, and other invertebrates; usually in pairs. Frequently exported through the aquarium trade. Distributed from the Andaman Sea eastward throughout the Indo-Malayan region, northward to southern Japan and the Great Barrier Reef. Coradion altivelis McCulloch, 1916 En - Highfin coralfish; Fr - Coradion à grande voile. Maximum total length about 15 cm. Inhabits outer reef slopes and drop-offs at depths of 3 to 15 m. Omnivorous; usually in pairs. Rarely exported through the aquarium trade. Distributed from the Andaman Sea eastward throughout the Indo-Malayan region, northward to southern Japan and the Great Barrier Reef. Perciformes: Percoidei: Chaetodontidae 3259 Coradion chrysozonus (Kuhl and van Hasselt in Cuvier, 1831) En - Orangebanded coralfish. Maximum total length about 15 cm. Inhabits outer reef slopes and drop-offs at depths of 3 to 15 m. Omnivorous; usually in pairs. Rarely exported through the aquarium trade. Distributed from the Andaman Sea eastward throughout the Indo-Malayan region, northward to southern Japan and the Great Barrier Reef. Coradion melanopus (Cuvier, 1831) En - Two-eyed coralfish. Maximum total length about 13 cm. Inhabits lagoons and coral reefs at depths of 3 to 15 m. Omnivorous; usually in pairs. Rarely exported through the aquarium trade. Distributed throughout the Indo-Malayan region eastward to Papua New Guinea. 3260 Bony Fishes Forcipiger flavissimus Jordan and McGregor, 1898 En - Forcepsfish; Fr - Chelmon à long bec. Maximum total length about 15 cm. -

Marine Science Virtual Lesson Biological Oceanography Photo Credit: Getty Images

Marine Science Virtual Lesson Biological Oceanography Photo credit: Getty Images • The study of how plants and animals interact with What is each other and their marine environment. • How organisms affect and are affected by chemical, Biological physical, and geological oceanography Oceanography? • Studies life in the ocean from tiny algae to giant blue whales Marine Environment Photo credit: Getty Images Biological Pump Some CO2 is • Carbon sink is part of the released through biological pump respiration • The pump includes upwelling that brings nutrient back up the water column • Releasing some CO2 through respiration Upwelling of nutrients Photosynthesis • Sunlight and CO2 is used to make sugar and oxygen • Can be used as fuel for an organism's movement and biological processes • Such as: circulatory system, digestive system, and respiration Where Can You Find Life in the Ocean • Plants and algae are found in the euphotic zone of the ocean • Where light reaches • Animals are found at all depths of the ocean • Most live-in the euphotic zone where there is more prey • 90% of species live and rely in euphotic zones • the littoral (close to shore) and sublittoral (coastal areas) zones Photo credit: libretexts.org Photo credit: Christian Sardet/CNRS/Tara Expéditions Plankton • Drifting animals • Follow the ocean currents (don’t swim) • Holoplankton • Spend entire lives in water column • Meroplankton • Temporary residents of plankton community • Larvae of benthic organisms Plankton 2.0 • Phytoplankton • Autotrophic (photosynthetic) Photo -

Findings and Recommendations of Effectiveness of the West Hawai'i Regional Fishery Management Area (WHRFMA)

Report to the Thirtieth Legislature 2020 Regular Session Findings and Recommendations of Effectiveness of the West Hawai'i Regional Fishery Management Area (WHRFMA) Prepared by: Department of Land and Natural Resources Division of Aquatic Resources State of Hawai'i In response to Section 188F-5, Hawaiʹi Revised Statutes November 2019 Findings and Recommendations of Effectiveness of the West Hawai'i Regional Fishery Management Area (WHRFMA) CORRESPONDING AUTHOR William J. Walsh Ph.D., Hawai′i Division of Aquatic Resources CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS Stephen Cotton, M.S., Hawai′i Division of Aquatic Resources Laura Jackson, B. S., Hawai′i Division of Aquatic Resources Lindsey Kramer, M.S., Hawai′i Division of Aquatic Resources, Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit Megan Lamson, M.S., Hawai′i Division of Aquatic Resources, Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit Stacia Marcoux, M.S., Hawai′i Division of Aquatic Resources, Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit Ross Martin B.S., Hawai′i Division of Aquatic Resources, Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit Nikki Sanderlin. B.S., Hawai′i Division of Aquatic Resources ii PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT This report, which covers the period between 2015 - 2019, is submitted in compliance with Act 306, Session Laws of Hawai′i (SLH) 1998, and subsequently codified into law as Chapter 188F, Hawaiʹi Revised Statutes (HRS) - West Hawai'i Regional Fishery Management Area. Section 188F-5, HRS, requires a review of the effectiveness of the West Hawai′i Regional Fishery Management Area shall be conducted every five years by the Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR), in cooperation with the University of Hawai′i (Section 188F-5 HRS). iii CONTENTS PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT ................................................................................................. -

Cartilaginous Fish: Sharks, Sawfish and Stingrays

Cartilaginous fish: Sharks, sawfish and stingrays. It may come as a surprise to some readers that there are sharks, sawfish and stingrays in the Mekong River, because most people connect these fishes with the big oceans. Most species in these groups are in fact strictly marine. However, several species have some tolerance to freshwater and have the ability to venture far up into rivers during their searches for food, while a few live their entire life in fresh water. Sharks, sawfish and stingrays are all cartilaginous fishes (the class Chondrichthyes), while all the species we have presented in Catch and Cultures supplement series until this point have been bony fish (the class Osteichthyes). Let us therefore start by looking at the characters that distinguish cartilaginous fish from bony fishes. As implied in the name, the skeleton in cartilaginous fish does not include bone but consists of cartilage, and all Fins supported by the fins are supported by horny horny structures structures rather than fin rays. Gill openings seen as Body covered with None of the species possess a a series of slits denticles swimbladder, the organ most bony fish use to prevent them from sinking to the bottom. Many cartilaginous fish species are therefore Mouth protrusible either bottom dwellers or accomplish neutral buoyancy by Specialized teeth arranged in rows maintaining a high fat or oil content A generalized cartilaginous fish, the milk shark in their tissues. (Rhizoprionodon acutus), which has been The gill openings in cartilaginous fish are not covered recorded from the Great Lake in Cambodia. with operculae, and are seen as a series of slits on the side of the fish just behind the head, or on the underside of the fish. -

SPC Beche-De-Mer Information Bulletin Has 13 Original S.W

ISSN 1025-4943 Issue 36 – March 2016 BECHE-DE-MER information bulletin Inside this issue Editorial Rotational zoning systems in multi- species sea cucumber fisheries This 36th issue of the SPC Beche-de-mer Information Bulletin has 13 original S.W. Purcell et al. p. 3 articles relating to the biodiversity of sea cucumbers in various areas of Field observations of sea cucumbers the western Indo-Pacific, aspects of their biology, and methods to better in Ari Atoll, and comparison with two nearby atolls in Maldives study and rear them. F. Ducarme p. 9 We open this issue with an article from Steven Purcell and coworkers Distribution of holothurians in the on the opportunity of using rotational zoning systems to manage shallow lagoons of two marine parks of Mauritius multispecies sea cucumber fisheries. These systems are used, with mixed C. Conand et al. p. 15 results, in developed countries for single-species fisheries but have not New addition to the holothurian fauna been tested for small-scale fisheries in the Pacific Island countries and of Pakistan: Holothuria (Lessonothuria) other developing areas. verrucosa (Selenka 1867), Holothuria cinerascens (Brandt, 1835) and The four articles that follow, deal with biodiversity. The first is from Frédéric Ohshimella ehrenbergii (Selenka, 1868) Ducarme, who presents the results of a survey conducted by an International Q. Ahmed et al. p. 20 Union for Conservation of Nature mission on the coral reefs close to Ari A checklist of the holothurians of Atoll in Maldives. This study increases the number of holothurian species the far eastern seas of Russia recorded in Maldives to 28. -

Aquarium Products in the Pacific Islands: a Review of the Fisheries, Management and Trade

Aquarium products in the Pacific Islands: A review of the fisheries, management and trade FAME Fisheries, Aquaculture and Marine Ecosystems Division Aquarium products in the Pacific Islands: A review of the fisheries, management and trade Robert Gillett, Mike A. McCoy, Ian Bertram, Jeff Kinch, Aymeric Desurmont and Andrew Halford March 2020 Pacific Community Noumea, New Caledonia, 2020 © Pacific Community (SPC) 2020 All rights for commercial/for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided that SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the document and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial/for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. Original SPC artwork may not be altered or separately published without permission. Original text: English Pacific Community Cataloguing-in-publication data Gillett, Robert Aquarium products in the Pacific Islands: a review of the fisheries, management and trade / Robert Gillett, Mike A. McCoy, Ian Bertram, Jeff Kinch, Aymeric Desurmont and Andrew Halford 1. Ornamental fish trade – Oceania. 2. Aquarium fish collecting – Oceania. 3. Aquarium fishes – Oceania. 4. Aquarium fishes – Management – Oceania. 5. Fishery – Management – Oceania. 6. Fishery – Marketing – Oceania. I. Gillett, Robert II. McCoy, Mike A. III. Bertram, Ian IV. Kinch, Jeff V. Desurmont, Aymeric VI. Halford, Andrew VII. Title -

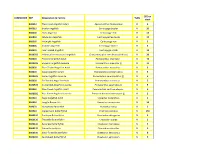

COMMANDE REF Désignation De L'article Taille QTE En Stock B00010 Three-Spot Angelfish Adult Apolemichthys Trimaculatus M 5 B005

QTE en COMMANDE REF Désignation de l'article Taille stock B00010 Three-spot Angelfish Adult Apolemichthys trimaculatus M 5 B00515 Bicolor Angelfish Centropyge bicolor M 35 B00530 Eibl's Angelfish Centropyge eibli M 13 B00540 White-tail Angelfish Centropyge flavicauda M 15 B00560 Midnight Angelfish Centropyge nox M 5 B00565 Keyhole Angelfish Centropyge tibicen M 5 B00570 Pearl-Scaled Angelfish Centropyge vroliki M 10 B010305 Yellowtail Vermiculated Angelfish Chaetodontoplus mesoleucus (Yellow) M 20 B02020 Emperor Angelfish Adult Pomacanthus imperator - M 10 B020205 Emperor Angelfish Juvenile Pomacanthus imperator (j) M 15 B02030 Blue-Girdled Angelfish Adult Pomacanthus navarchus - M 6 B02040 Koran Angelfish Adult Pomacanthus semicirculatus M 5 B020405 Koran Angelfish Juvenile Pomacanthus semicirculatus (j) M 6 B02050 Six-Banded Angelfish Adult Pomacanthus sexstriatus - M 5 B020505 Six-Banded Angelfish Juvenile Pomacanthus sexstriatus (j) M 5 B02060 Blue-Faced Angelfish Adult Pomacanthus xanthometopon - M 6 B020605 Blue-Faced Angelfish Juvenile Pomacanthus xanthometopon (j) M 5 B02510 Regal Angelfish Adult Pygoplites diacanthus - M 2 B04010 Longfin Bannerfish Heniochus acuminatus M 10 B04070 Humphead Bannerfish Heniochus varius M 2 B04510 Copperband Butterflyfish Chelmon rostratus M 150 B060110 Bantayan Butterflyfish Chaetodon adiergastos M 3 B060130 Threadfin Butterflyfish Chaetodon auriga M 2 B060140 Baroness Butterflyfish Chaetodon baronessa M 5 B060170 Citron Butterflyfish Chaetodon citrinellus M 5 B060190 Black-Finned Butterflyfish -

Petition to Prevent the Import of Illegally Caught Tropical Fish Into the United States and Require Testing and Certification

Sent Via First Class Mail and E-mail March 8, 2016 Eileen Sobeck Assistant Administrator for Fisheries NOAA Fisheries 1315 East-West Highway Silver Spring, MD 20910 [email protected] Commissioner R. Gil Kerlikowske U.S. Customs and Border Protection 1300 Pennsylvania Ave. NW Washington, DC 20229 [email protected] Daniel M. Ashe, Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C. Street, NW, Room 3331 Washington, DC 20240 [email protected] Re: Petition to Prevent the Import of Illegally Caught Tropical Fish into the United States and Require Testing and Certification Dear Ms. Sobeck, Mr. Kerlikowske, and Mr. Ashe: Each year, cyanide fishing – a fishing method used to collect tropical marine fish for the aquarium trade – likely kills tens of millions of tropical marine animals, including thousands of acres of corals around the globe.1 Although this deadly practice is almost universally banned in nations that are the source of the fish, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (“NOAA”) estimates that 90 percent of the ten to thirty million tropical marine aquarium fish 1 Fred Pearce, Cyanide: an Easy but Deadly Way to Catch Fish, WORLD WILDLIFE FUND GLOBAL (Jan. 29, 2003), http://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?5563/Cyanide-an-easy-but-deadly-way-to-catch-fish; Daniel Thornhill, Ecological Impacts and Practices of the Coral Reef Wildlife Trade, DEFENDERS OF WILDLIFE, at *7 (2012), available at http://www.defenders.org/sites/default/files/publications/ecological-impacts-and-practices-of-the-coral-reef-wildlife- trade.pdf [hereinafter Thornhill, Ecological Impacts and Practices of the Coral Reef Wildlife Trade].