The Traditions of the Noble Ones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

River Dhamma

Arrow River Forest Hermitage Spring/Summer 2019 RIVER DHAMMA ARROW RIVER FRONT PAGE NEWS Abbots’ Meeting at the Hermitage About the Thai Forest Tradition The Thai Forest tradition is the branch of Arrow River is honoured to be hosting the 2019 Theravāda Buddhism in Thailand that most strictly North American Abbots’ Meeting from September upholds the original monastic rules of discipline 4 to 11. Seven abbots from monasteries in the laid down by the Buddha. The Forest tradition also Ajahn Chah tradition from Canada and the United most strongly emphasizes meditative practice and States will gather for fellowship and to enjoy the the realization of enlightenment as the focus of peace and solitude of the Hermitage. monastic life. Forest monasteries are primarily Needless to say, this event is grand undertaking oriented around practicing the Buddha’s path of for Arrow River. We have made a plan of priorities contemplative insight, including living a life of to complete to get things ship-shape for the visit. discipline, renunciation, and meditation in order to As we are an organization with a tight budget and fully realize the inner truth and peace taught by a small group of volunteers, we are looking for the Buddha. Living a life of austerity allows forest some help. monastics to simplify and refine the mind. This refinement allows them to clearly and directly Here’s what you can do: explore the fundamental causes of suffering within 1. Come out to Arrow River to help with their heart and to inwardly cultivate the path preparations. There will be scheduled work leading toward freedom from suffering and days, but you can also come on your own supreme happiness. -

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

The Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination

Journal of Buddhist Ethics ISSN 1076-9005 http://blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/ Volume 22, 2015 The Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination Bhikkhu Anālayo University of Hamburg Copyright Notice: Digital copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no change is made and no alteration is made to the content. Reproduction in any other format, with the exception of a single copy for private study, requires the written permission of the author. All en- quiries to: [email protected]. The Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination Bhikkhu Anālayo1 Abstract With this paper I examine the narrative that in the Cullavagga of the Theravāda Vinaya forms the background to the different rules on bhikkhunī ordination, alternating between translations of the respective portions from the original Pāli and discussions of their implications. An appendix to the paper briefly discusses the term paṇḍaka. Introduction In what follows I continue exploring the legal situation of bhikkhunī or- dination, a topic already broached in two previous publications. In “The Legality of Bhikkhunī Ordination” I concentrated in particular on the legal dimension of the ordinations carried out in Bodhgayā in 1998.2 Based on an appreciation of basic Theravāda legal principles, I discussed the nature of the garudhammas and the need for a probationary training 1 Numata Center for Buddhist Studies, University of Hamburg, and Dharma Drum Insti- tute of Liberal Arts, Taiwan. I am indebted to bhikkhu Ariyadhammika, bhikkhu Bodhi, bhikkhu Brahmāli, bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā, and Petra Kieffer-Pülz for commenting on a draft version of this article. 2 Anālayo (“The Legality”). Anālayo, The Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination 402 as a sikkhamānā, showing that this is preferable but not indispensable for a successful bhikkhunī ordination. -

The Island, the Refuge, the Beyond

T H E I S L A N D AN ANTHOLOGY OF THE BUDDHA’S TEACHINGS ON NIBBANA Ajahn Pasanno & Ajahn Amaro T H E I S L A N D An Anthology of the Buddha’s Teachings on Nibbæna Edited and with Commentary by Ajahn Pasanno & Ajahn Amaro Abhayagiri Monastic Foundation It is the Unformed, the Unconditioned, the End, the Truth, the Other Shore, the Subtle, the Everlasting, the Invisible, the Undiversified, Peace, the Deathless, the Blest, Safety, the Wonderful, the Marvellous, Nibbæna, Purity, Freedom, the Island, the Refuge, the Beyond. ~ S 43.1-44 Having nothing, clinging to nothing: that is the Island, there is no other; that is Nibbæna, I tell you, the total ending of ageing and death. ~ SN 1094 This book has been sponsored for free distribution SABBADÆNAM DHAMMADÆNAM JINÆTI The Gift of Dhamma Excels All Other Gifts © 2009 Abhayagiri Monastic Foundation 16201 Tomki Road Redwood Valley, CA 95470 USA www.abhayagiri.org Web edition, released June 13, 2009 VI CONTENTS Prefaces / VIII Introduction by Ajahn Sumedho / XIII Acknowledgements / XVII Dedication /XXII SEEDS: NAMES AND SYMBOLS 1 What is it? / 25 2 Fire, Heat and Coolness / 39 THE TERRAIN 3 This and That, and Other Things / 55 4 “All That is Conditioned…” / 66 5 “To Be, or Not to Be” – Is That the Question? / 85 6 Atammayatæ: “Not Made of That” / 110 7 Attending to the Deathless / 123 8 Unsupported and Unsupportive Consciousness / 131 9 The Unconditioned and Non-locality / 155 10 The Unapprehendability of the Enlightened / 164 11 “‘Reappears’ Does Not Apply…” / 180 12 Knowing, Emptiness and the -

Mahasi Sayadaw's Revolution

Deep Dive into Vipassana Copyright © 2020 Lion’s Roar Foundation, except where noted. All rights reserved. Lion’s Roar is an independent non-profit whose mission is to communicate Buddhist wisdom and practices in order to benefit people’s lives, and to support the development of Buddhism in the modern world. Projects of Lion’s Roar include Lion’s Roar magazine, Buddhadharma: The Practitioner’s Quarterly, lionsroar.com, and Lion’s Roar Special Editions and Online Learning. Theravada, which means “Way of the Elders,” is the earliest form of institutionalized Buddhism. It’s a style based primarily on talks the Buddha gave during his forty-six years of teaching. These talks were memorized and recited (before the internet, people could still do that) until they were finally written down a few hundred years later in Sri Lanka, where Theravada still dominates – and where there is also superb surf. In the US, Theravada mostly man- ifests through the teaching of Vipassana, particularly its popular meditation technique, mindfulness, the awareness of what is hap- pening now—thoughts, feelings, sensations—without judgment or attachment. Just as surfing is larger than, say, Kelly Slater, Theravada is larger than mindfulness. It’s a vast system of ethics and philoso- phies. That said, the essence of Theravada is using mindfulness to explore the Buddha’s first teaching, the Four Noble Truths, which go something like this: 1. Life is stressful. 2. Our constant desires make it stressful. 3. Freedom is possible. 4. Living compassionately and mindfully is the way to attain this freedom. 3 DEEP DIVE INTO VIPASSANA LIONSROAR.COM INTRODUCTION About those “constant desires”: Theravada practitioners don’t try to stop desire cold turkey. -

Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements

Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Alan Robert Lopez Chiang Mai , Thailand ISBN 978-1-137-54349-3 ISBN 978-1-137-54086-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-54086-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956808 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Cover image © Nickolay Khoroshkov / Alamy Stock Photo Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Nature America Inc. -

The Pāṃsukūlacīvara ! Towards an Anthropology of a Trans-Traditional Buddhist Robe ! ! ! !

! ! ! ! ! ! Faculty of Arts and Philosophy SIMON BULTYNCK ! ! ! ! The Pāṃsukūlacīvara ! Towards an anthropology of a trans-traditional Buddhist robe ! ! ! ! Master’s dissertation submitted to obtain the degree of Master of Asian Languages and Cultures ! 2016 ! ! ! ! ! Supervisor! ! Prof.!dr.!Ann!Heirman! ! ! ! Department!of!Languages!and!Cultures! ! Dean! ! Prof.!dr.!Marc!Boone! Rector! ! Prof.!dr.!Anne!De!Paepe! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! iii! ! ! iv! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! while striving for death’s army’s rout the ascetic clad in rag-robe clout got from a rubbish heap, shines bright mārasenavighātāya as mail-clad warrior paṃsukūladharo yati in the fight. sannaddhakavaco yuddhe ! khattiyo viya sobhati this robe the world’s great teacher wore, pahāya kāsikādīni leaving rare Kási cloth varavatthāni dhāritaṃ and more; yaṃ lokagarunā ko taṃ of rags from off paṃsukūlaṃ na dhāraye a rubbish heap who would not have tasmā hi attano bhikkhu a robe to keep? paṭiññaṃ samanussaraṃ ! yogācārānukūlamhi minding the words paṃsukūle rato siyāti he did profess ! when he went ! ! into homelessness, ! let him to wear ! such rags delight ! as!one!! ! in!seemly!garb!bedight.*! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! v! ! ! ! ! vi! ! Abstract Superlatives in academics are scarce; in humanities they are almost taboo. And yet it is probably fair to say that one of the most significant robes of all Buddhist monastic attire is the pāṃsukūlacīvara. Often poorly translated as ‘robe from the dust-heap’, this trans- tradition monastic type of dress, patched from cast-off rags, has been charged with du- bious symbolism and myth throughout Buddhist literature. This thesis aims to bridge the gap between anthropological and text-critical research on the topic and to further widen both the scope of its study. -

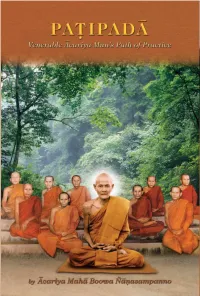

Full Patipada.Pdf

PaṬipadā Venerable Ãcariya Mun’s Path of Practice By Venerable Ãcariya Mahã Boowa Ñãõasampanno Translated by Venerable Ãcariya Paññãvaððho THIS BOOK IS A GIFT OF DHAMMA AND PRINTED FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY. “The gift of Dhamma excels all other gifts” − The Buddha © 2005 by Venerable Äcariya Mahå Boowa Ñå¾asampanno This book is a free gift of Dhamma & may not be offered for sale. All Commercial Rights Reserved. The Dhamma should not be sold like goods in the market place. Permission to reproduce in any way for free distribution, as a gift of Dhamma, is hereby granted and no further permission need be obtained. Reproduction in any way for commercial gain is prohibited. Author: Venerable Ācariya Mahā Boowa Ñāṇasampanno Thera Translator: Venerable Ācariya Paññāvaḍḍho Thera ISBN: 974-93757-9-3 Second Printing: December, 2005 Printed in Thailand by Silpa Siam Packaging & Printing Co., Ltd. Tel: (662) 444-3351-9 Any Inquiries can be addressed to: Forest Dhamma Books Baan Taad Forest Monastery Baan Taad, Ampher Meung Udon Thani, 41000 Thailand [email protected] www.ForestDhammaBooks.com Contents Translator’s Introduction i 1 Kammaäähåna 1 2 Training the Mind 29 3 The Story of the White-robed Upåsaka 51 4 More About Training & Venerable Ajaan Mun’s Talk 65 Behaviour & Practice in a Forest Monastery 83 More About Training & Discipline 90 5 Stories of Bhikkhus Who Practice 103 A First Encounter With a Tiger 106 6 The Ascetic Practices (Dhutangas) 113 7 The Story of Venerable Ajaan Chob 129 The Devatās Visit Him to Hear Dhamma 133 An Arahant Comes -

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

Buddhist Ethics in Japan and Tibet: a Comparative Study of the Adoption of Bodhisattva and Pratimoksa Precepts

University of San Diego Digital USD Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship Department of Theology and Religious Studies 1994 Buddhist Ethics in Japan and Tibet: A Comparative Study of the Adoption of Bodhisattva and Pratimoksa Precepts Karma Lekshe Tsomo PhD University of San Diego, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Digital USD Citation Tsomo, Karma Lekshe PhD, "Buddhist Ethics in Japan and Tibet: A Comparative Study of the Adoption of Bodhisattva and Pratimoksa Precepts" (1994). Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship. 18. https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty/18 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Buddhist Behavioral Codes and the Modern World An Internationa] Symposium Edited by Charles Weihsun Fu and Sandra A. Wawrytko Buddhist Behavioral Codes and the Modern World Recent Titles in Contributions to the Study of Religion Buddhist Behavioral Cross, Crescent, and Sword: The Justification and Limitation of War in Western and Islamic Tradition Codes and the James Turner Johnson and John Kelsay, editors The Star of Return: Judaism after the Holocaust -

Early Buddhist Concepts in Today's Language

1 Early Buddhist Concepts In today's language Roberto Thomas Arruda, 2021 (+55) 11 98381 3956 [email protected] ISBN 9798733012339 2 Index I present 3 Why this text? 5 The Three Jewels 16 The First Jewel (The teachings) 17 The Four Noble Truths 57 The Context and Structure of the 59 Teachings The second Jewel (The Dharma) 62 The Eightfold path 64 The third jewel(The Sangha) 69 The Practices 75 The Karma 86 The Hierarchy of Beings 92 Samsara, the Wheel of Life 101 Buddhism and Religion 111 Ethics 116 The Kalinga Carnage and the Conquest by 125 the Truth Closing (the Kindness Speech) 137 ANNEX 1 - The Dhammapada 140 ANNEX 2 - The Great Establishing of 194 Mindfulness Discourse BIBLIOGRAPHY 216 to 227 3 I present this book, which is the result of notes and university papers written at various times and in various situations, which I have kept as something that could one day be organized in an expository way. The text was composed at the request of my wife, Dedé, who since my adolescence has been paving my Dharma with love, kindness, and gentleness so that the long path would be smoother for my stubborn feet. It is not an academic work, nor a religious text, because I am a rationalist. It is just what I carry with me from many personal pieces of research, analyses, and studies, as an individual object from which I cannot separate myself. I dedicate it to Dede, to all mine, to Prof. Robert Thurman of Columbia University-NY for his teachings, and to all those to whom this text may in some way do good. -

BUDDHISM, MEDITATION, and the NEGOTIATION of the PUBLIC SPHERE by Leana Marie Rudolph a Capstone Project Submitted for Graduatio

BUDDHISM, MEDITATION, AND THE NEGOTIATION OF THE PUBLIC SPHERE By Leana Marie Rudolph A capstone project submitted for Graduation with University Honors May 20, 2021 University Honors University of California, Riverside APPROVED Dr. Matthew King Department of Religious Studies Dr. Richard Cardullo, Howard H Hays Jr. Chair University Honors ABSTRACT This capstone serves to map and gather the oral histories of formerly undocumented Buddhist communities pertaining to their lived experiences in the Inland Empire. The ethnographic fieldwork conducted of 11 sites over the period of 12 months explored the intersection of diaspora, economy, and religious affiliation. This research begins to explore this junction by undertaking a qualitative and quantitative study that will map Buddhist life in the Inland Empire today. It will include interviews, providing oral histories, and will be accessible through a GIS map, helping Religious Studies and Anthropologist scholars to locate these sites and have background information on these locations. The Inland Empire represents many heavily populated, post-agricultural, and manufacturing areas in America today, which since the 1970s and especially since 2008 has suffered from many economic and social crises related to suburban poverty, as well as waves of demographic changes. Taking the Inland Empire as a petri dish for broader trends at the intersection of religion, economy, and the social in the American public sphere today, this capstone project hopes to determine how Buddhism forms at these intersections, what new stories about life in the Inland Empire Buddhist sites and communities help illuminate, and what forms of digital interfacing best brings anthropological analyses to the publics it examines.