Provisional Not4es on Pelham's Earliest Settlers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alfred Romer – Wikipedia

Alfred Romer – Wikipedia https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Romer aus Wikipedia, der freien Enzyklopädie Alfred Sherwood Romer (* 28. Dezember 1894 in White Plains, New York; † 5. November 1973) war ein US-amerikanischer Paläontologe. Sein Fachgebiet war die Evolution der Wirbeltiere. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Leben 2 Romer-Lücke 3 Auszeichnungen und Ehrungen 4 Schriften 5 Weblinks 6 Einzelnachweise Leben Alfred Sherwood Romer wurde in White Plains, New York geboren, wo er seinen High-School-Abschluss machte. Danach arbeitete er ein Jahr lang als Angestellter bei der Eisenbahn und entschloss sich dann doch für den Besuch eines College. Mit Hilfe eines Stipendiums vom Amherst College konnte er dort Geschichte und deutsche Literatur studieren. Durch häufige Besuche des American Museum of Natural History entdeckte er seine Begeisterung für naturkundliche Fossilien. Bei Ausbruch des Ersten Weltkriegs meldete er sich als Freiwilliger zum Kriegsdienst und wurde sofort in Frankreich eingesetzt. 1919 kam er zurück nach New York und nahm das Studium der Biologie an der Columbia University auf, das er bereits zwei Jahre später mit der Promotion abschloss. Danach war er als wissenschaftliche Hilfskraft an der Bellevue Medical School der New York University beschäftigt und lehrte insbesondere Histologie, Embryologie und Allgemeine Anatomie. 1923 erhielt er einen Ruf von der Universität Chicago, wo er seine spätere Ehefrau Ruth kennenlernte, mit der er drei Kinder hatte. In Chicago fand er Bedingungen vor, die es ihm ermöglichten, sein Hauptinteresse zu intensivieren - die Paläontologie. So entstanden in den Jahren von 1925 bis 1935 37 Fachartikel, die sich mit diesem Thema befassten. 1934 wurde er zum Professor für Biologie an der Harvard University ernannt. -

Wi-Hi GERYIS Ple De Ra L' Is M; Zqiixotrqes

’ ' “ ‘ WI - H I G E R Y I s PLE DE R A L i s M; ‘ z Q iI x o r Qe s a rol “ Q Fix- ? t Cl i green s 6 (h a fis m w r a nk “ W. ’ — mn of efi n t st t a . n From th e Boston Morning P o E x r o u m ent J erso , a d place i over the bones TH E I DE NTIT Y OF TH E OL D H AR TFOR D CONVE N o f F s t for ederali m , | hank themselves having com ‘ ‘ TI ON FE DE R AL I S TS WI TH TH E MODE R N WH I G ellediu s to ~ r t p restore it to its igh place , with its H AR R I EON P AR TY CA R E FUL L Y I L L U STR ATE D e t , true inscription , and expos the rottenness i h as BY L I VI NG S P E CI ME NS AND DE DI CATE D To TH E ' , beemsm ade to cove r; We would p ain no living - Y OU NG ME N OF TH E UNI ON. m o anm nnected with those scenes . Many of them f b in Old party distinctions are revived The und are venerabl e , an d most estima le private life . m g and national debt and National Bank sys We would tread lightly on the ashes of the dead ; t Of w h ff w — s — — ems. -

Proceedings of the Open University Geological Society

Proceedings of the Open University Geological Society Volume 4 2018 Including lecture articles from the AGM 2017, the Milton Keynes Symposium 2017, OUGS Members’ field trip reports, the Annual Report for 2017, and the 2017 Moyra Eldridge Photographic Competition winning and highly commended photographs Edited and designed by: Dr David M. Jones 41 Blackburn Way, Godalming, Surrey GU7 1JY e-mail: [email protected] The Open University Geological Society (OUGS) and its Proceedings Editor accept no responsibility for breach of copyright. Copyright for the work remains with the authors, but copyright for the published articles is that of the OUGS. ISSN 2058-5209 © Copyright reserved Proceedings of the OUGS 4 2018; published 2018; printed by Hobbs the Printers Ltd, Totton, Hampshire Evolution of life on land: how new Scottish fossils are re-writing our under- standing of this important transition Dr Tim Kearsey BGS Edinburgh Romer’s gap — a hole in our understanding t has long been understood that at some point in the evolution Meanwhile at a quarry called East Kirkton Quarry near Iof vertebrates there was a transition point where they moved Edinburgh in Scotland vertebrate fossils were discovered that are from mainly subsiding in water to living on land. However, until 10 million years younger than the Greenland fossils. These include recently there had been no fossil evidence that documented how Westlothiana, which is thought to be the first amniote (egg-layer) vertebrate life stepped from water to land. This significant hole in or possibly early reptile (Smithson and Rolfe 1990) and scientific knowledge of evolution is referred to as Romer’s gap Balanerpeton an extinct genus of temnospondyl amphibian. -

<Kommontoaitij of Fhiissacijusms

RULES AND ORDERS, TO BE OBSERVED IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES O F T H E <Kommontoaitij of fHiissacijusms, f o b THE YEAR 1837. PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE HOUSE. BOSTON: DUTTON AND WENTWORTH, STATE PRINTERS. 1337. Knies and Orders o f the House. C H A P T E R I. O f the Duties and Powers o f the Speaker. I. T h e Speaker shall take the Chair every day at the hour to which the House shall have adjourned ; shall call the Members to order; and, on the appear ance o f a quorum, shall proceed to business. II. He shall preserve decorum and order; may speak to points o f order in preference to other Members ; and shall decide all questions o f order, subject to an appeal to the House on motion regularly seconded. III. He shall declare all votes; but if any Member rises to doubt a vote, the Speaker shall order a re turn o f the number voting in the affirmative, and in the negative, without any further debate upon the question. IV. He shall rise to put a question, or to address the House, but may read sitting. V. In all cases the Speaker may vote. VI. When the House shall determine to go into a Committee o f the whole House, the Speaker shall appoint the Member who shall take the Chair. VII. When any Member shall require a question to be determined by yeas and nays, the Speaker shall take the sense o f the House in that manner, provided one third o f the members present are in favor o f it 4 Duties o f the Speaker. -

Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge Summary

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge Summary Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Impact Statement August 2015 U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge Summary Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Impact Statement August 2015 Summary This document summarizes the draft comprehensive conservation plan (CCP) Overview and environmental impact statement (EIS) for the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge (Conte Refuge, refuge). The draft CCP/EIS evaluates four alternatives for managing the refuge over the next 15 years. To download the full draft CCP/EIS, visit: http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Silvio_O_Conte/what_we_do/ conservation.html The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is releasing the draft CCP/EIS for a 90-day public comment period. During this comment period, we hope you will take the opportunity to review the document and provide us with comments. We will be accepting written comments, as well as oral comments at four public hearings. For more information on how to submit written comments, see the end of this summary document. For public hearing dates, times, and locations, please visit the website listed above. The comment method does not impact how they will be considered as part of this public process (i.e., oral comments do not carry more weight than written comments). We recognize that the draft CCP/EIS is very lengthy, so we have developed this summary to highlight the major proposals in the draft plan and point readers to where they can find more detailed information in the full-text version of the draft plan. -

Calculated for the Use of the State of Massachusetts-Bay

Mil Digitized by tine Internet Arcliive in 2009 witli funding from University of IVIassacliusetts, Boston Iittp://www.arcliive.org/details/pocketalmanackfo1807amer jB^''^^mfff^fi^i!!uiutiXj»f^;'^' ^^ ^p^i:^"P^^^ Bf^taSH THE J i MASSACHUSETTS i f AND United States Calendar; For the Year of our LORD 180 7, and the Thiity-firft oi American Indetendence, CONTAINING Civil, Ecde^ajlical, Judkial, and Military Lifts in MASSACHUSETTS ; AssaciATioNs, and Corporate Institutions, for littraiy, ag ncuUural, <ind cUariiablt Furpoitb, I Lijl of PoiT-TowNS in Majjachufdts^ with I'm 'I' Names of tkt Post-Masters. I ALSO, Catalogues of the Officers of the .1 GENERAL GOVERNMENT, With its feveral Deparanents and Eitablirhnicnts ; Time^ o^ the Siumgi. of the feveral Courts ; Goveinors in each State , PuDiic Duties, (&:c. USEFUL TABLES; And a Variety of oiher interefting Articles. 1> BOSTON : t Publilhcd by JOHN \\EsT, and MANNING & LORINO. Sold, wholcfale and retail, at their Book Stores, Cornhill. > fS^tpSfx^arSgSi^i^ci .^j^Ad^xasw^^^o* , — : ECLIPSES FOR 1807. THER£ will be four Eclipfcs this year; two of the Sun anJ iwc of the Mooo. as follows : I. The firft will he of the Moon, May 21ft, lih.^SiiN in the mornuig ; and of courfe invifible. II. 7 he fecond will be of the Sun, June 6th, oh. 40m. in the morning ; which will llkewift; be invi^ble in rhp wellern conrnieHt, bnt vifible and central in the fouthein p^ri s of the Eh(1 Indirs. ' HI. The third will be a vifible eclipfe of the Moon, November 15th ; and by calculation as follows ^. -

H. Doc. 108-222

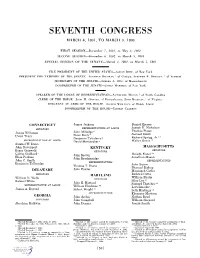

SEVENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1801, TO MARCH 3, 1803 FIRST SESSION—December 7, 1801, to May 3, 1802 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1802, to March 3, 1803 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1801, to March 5, 1801 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—AARON BURR, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—ABRAHAM BALDWIN, 1 of Georgia; STEPHEN R. BRADLEY, 2 of Vermont SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—NATHANIEL MACON, 3 of North Carolina CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JOHN H. OSWALD, of Pennsylvania; JOHN BECKLEY, 4 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH WHEATON, of Rhode Island DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT James Jackson Daniel Hiester Joseph H. Nicholson SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas Plater James Hillhouse John Milledge 6 Peter Early 7 Samuel Smith Uriah Tracy 12 Benjamin Taliaferro 8 Richard Sprigg, Jr. REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE 13 David Meriwether 9 Walter Bowie Samuel W. Dana John Davenport KENTUCKY MASSACHUSETTS SENATORS Roger Griswold SENATORS 5 14 Calvin Goddard John Brown Dwight Foster Elias Perkins John Breckinridge Jonathan Mason John C. Smith REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Benjamin Tallmadge John Bacon Thomas T. Davis Phanuel Bishop John Fowler DELAWARE Manasseh Cutler SENATORS MARYLAND Richard Cutts William Eustis William H. Wells SENATORS Samuel White Silas Lee 15 John E. Howard Samuel Thatcher 16 REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE William Hindman 10 Levi Lincoln 17 James A. Bayard Robert Wright 11 Seth Hastings 18 REPRESENTATIVES Ebenezer Mattoon GEORGIA John Archer Nathan Read SENATORS John Campbell William Shepard Abraham Baldwin John Dennis Josiah Smith 1 Elected December 7, 1801; April 17, 1802. -

Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 11-12-1992 Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Earman, Cynthia Diane, "Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830" (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOARDINGHOUSES, PARTIES AND THE CREATION OF A POLITICAL SOCIETY: WASHINGTON CITY, 1800-1830 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Cynthia Diane Earman A.B., Goucher College, 1989 December 1992 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions. -

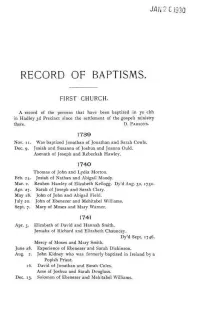

Record of Baptisms

JAN 2 C J930 RECORD OF BAPTISMS. FIRST CHURCH. A record of the persons that have been baptized in ye chh in Hadley 3d Precinct since the settlement of the gospell ministry there. D. PARSONS. 1739 Nov. 11. Was baptized Jonathan of Jonathan and Sarah Cowls. Dec. 9. Josiah and Susanna of Joshua and Joanna Ould. Asenath of Joseph and Rebeckah Hawley. 1740 Thomas of John and Lydia Morton. Feb. 24. Josiah of Nathan and Abigail Moody. Mar. 2. Reuben Hawley of Elizabeth Kellogg. Dy'd Aug. 30, 1750. Apr. 27. Sarah of Joseph and Sarah Clary. May 18. John of John and Abigail Field. July 20. John of Ebenezer and Mehitabel Williams. Sept. 7. Mary of Moses and Mary Warner. 1741 Apr. 5. Elizabeth of David and Hannah Smith. Jerusha of Richard and Elizabeth Chauncey. Dy'd Sept. 1746. Mercy of Moses and Mary Smith. June 28. Experience of Ebenezer and Sarah Dickinson. Aug. 2. John Kidney who was formerly baptized in Ireland by a Popish Priest. 16. David of Jonathan and Sarah Coles. Ame of Joshua and Sarah Douglass. Dec. 13. Solomon of Ebenezer and Mehitabel Williams. 2 TOWN OF AMHERST, MASSACHUSETTS 1742 Jan. 3. Ephraim of Ephraim and Dorothy Kellogg. Apr. 18. Abigail of Samuel and Abigail Ingram. July 11. Abigail of John and Abigail Field. Oct. 3. Mary of John and Mary Cowls. Nov. 4. Eunice of Elisha and Eunice Perkins. Gersham of Joseph and Sarah Clary. 1743 Apr. 10. Zachariah of Samuel and Sarah Hawley. Oct. 2. Martha Boltwood of John and Abigail Field. 1744 Jan. -

Alfred Romer to Hugh L

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ALFRED SHERWOOD ROMER 1894—1973 A Biographical Memoir by EDWIN H. COLBERT Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1982 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. ALFRED SHERWOOD ROMER December 28, 1894 -November 5, 1973 BY EDWIN H. COLBERT LFRED SHERWOOD ROMER was a man of many aspects: a A profound scholar whose studies of vertebrate evolution based upon the comparative anatomy of fossils established him throughout the world as an outstanding figure in his field; a gifted teacher who trained several generations of paleontologists and anatomists; an effective administrator who never allowed the burden of office to diminish his re- search activities; a lucid writer whose books and scientific papers were and are of inestimable value; and a warm per- son, loved and admired by family, friends, and colleagues. Al, as he was universally known to his friends, lived a full and rewarding life, during which he led and influenced paleon- tologists, anatomists, and evolutionists in many lands. His absence is keenly felt. A1 Romer was born in White Plains, New York on December 28, 1894, the son of a newspaper man who was editor, and sometimes owner, of several small-town news- papers in Connecticut and New York, and who later worked for the Associated Press. On the paternal side he was de- scended from Jacob Romer, an emigrant from Ziirich who settled among the Dutch residents of the Hudson River Val- ley about 1725. -

The Evolution and Function of Theropod Dinosaur Tails

University of Alberta The Evolution and Function of Theropod Dinosaur Tails by Walter Scott Persons A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Systematics and Evolution Department of Biological Sciences ©Walter Scott Persons Fall 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1 Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91864-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91864-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Development, Anatomy, and Phylogenetic Relationships of Jawless Vertebrates and Tests of Hypotheses About Early Vertebrate Evolution

Development, Anatomy, and Phylogenetic Relationships of Jawless Vertebrates and Tests of Hypotheses about Early Vertebrate Evolution by Tetsuto Miyashita A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Systematics and Evolution Department of Biological Sciences University of Alberta © Tetsuto Miyashita, 2018 ii ABSTRACT The origin and early evolution of vertebrates remain one of the central questions of comparative biology. This clade, which features a breathtaking diversity of complex forms, has generated profound, unresolved questions, including: How are major lineages of vertebrates related to one another? What suite of characters existed in the last common ancestor of all living vertebrates? Does information from seemingly ‘primitive’ groups — jawless vertebrates, cartilaginous fishes, or even invertebrate outgroups — inform us about evolutionary transitions to novel morphologies like the neural crest or jaw? Alfred Romer once likened a search for the elusive vertebrate archetype to a study of the Apocalypse: “That way leads to madness.” I attempt to address these questions using extinct and extant cyclostomes (hagfish, lampreys, and their kin). As the sole living lineage of jawless vertebrates, cyclostomes diverged during the earliest phases of vertebrate evolution. However, precise relationships and evolutionary scenarios remain highly controversial, due to their poor fossil record and specialized morphology. Through a comparative analysis of embryos, I identified significant developmental similarities and differences between hagfish and lampreys, and delineated specific problems to be explored. I attacked the first problem — whether cyclostomes form a clade or represent a grade — in a description and phylogenetic analyses of a new, nearly complete fossil hagfish from the Cenomanian of Lebanon.