Selected Principals' Perceptions of Gentrification's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mortgage-Backed Securities & Collateralized Mortgage Obligations

Mortgage-backed Securities & Collateralized Mortgage Obligations: Prudent CRA INVESTMENT Opportunities by Andrew Kelman,Director, National Business Development M Securities Sales and Trading Group, Freddie Mac Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) have Here is how MBSs work. Lenders because of their stronger guarantees, become a popular vehicle for finan- originate mortgages and provide better liquidity and more favorable cial institutions looking for investment groups of similar mortgage loans to capital treatment. Accordingly, this opportunities in their communities. organizations like Freddie Mac and article will focus on agency MBSs. CRA officers and bank investment of- Fannie Mae, which then securitize The agency MBS issuer or servicer ficers appreciate the return and safety them. Originators use the cash they collects monthly payments from that MBSs provide and they are widely receive to provide additional mort- homeowners and “passes through” the available compared to other qualified gages in their communities. The re- principal and interest to investors. investments. sulting MBSs carry a guarantee of Thus, these pools are known as mort- Mortgage securities play a crucial timely payment of principal and inter- gage pass-throughs or participation role in housing finance in the U.S., est to the investor and are further certificates (PCs). Most MBSs are making financing available to home backed by the mortgaged properties backed by 30-year fixed-rate mort- buyers at lower costs and ensuring that themselves. Ginnie Mae securities are gages, but they can also be backed by funds are available throughout the backed by the full faith and credit of shorter-term fixed-rate mortgages or country. The MBS market is enormous the U.S. -

Secondary Mortgage Market

8-6 Legal Considerations - Real Estate Contracts - Financing Basic Appraisal Principles Other Sources of Funds Pension Funds and Insurance Companies Pension funds and insurance companies have recently had such growth that they have been looking for new outlets for their investments. They manage huge sums of money, and traditionally have invested in ultra-conservative instruments, such as government bonds. However, the booming economy of the 1990s, and corresponding budget surpluses for the federal government, left a shortage of treasury securities for these companies to buy. They had to find other secure investments, such as mortgages, to invest their assets. The higher yields available with Mortgage Backed Securities were also a plus. The typical mortgage- backed security will carry an interest rate of 1.00% or more above a government security. Pension funds and insurance companies will also provide direct funding for larger commercial and development loans, but will rarely loan for individual home mortgages. Pension funds are regulated by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (1974). Secondary Mortgage Market The secondary mortgage market buys and sells mortgages created in the primary mortgage market (the link to Wall Street). A valid mortgage is always assignable by the mortgagee, allowing assignment or sale of the rights in the mortgage to another. The mortgage company can sell the loan, the servicing, or both. If just the loan is sold without the servicing, the original lender will continue to collect payments, and the borrower will never know the loan was sold. If the lender sells the servicing, the company collecting the payments will change, but the terms of the loan will stay the same. -

{670031-4} 1 Collateral Assignment of Leases And

COLLATERAL ASSIGNMENT OF LEASES AND RENTS THIS COLLATERAL ASSIGNMENT OF LEASES AND RENTS (this “Assignment”) is entered into as of _________, 2021, by and between Yingling Aircraft, Inc., a Kansas corporation (“Assignor”); and INTRUST Bank, N.A., a national banking association (“Lender”). Recitals A. Wichita Airport Authority, Wichita, Kansas (“Lessor”) and LeaseCorp Financial, Inc., a Kansas corporation, entered into that certain Master Lease Agreement dated June 12, 2012, which was assigned by LeaseCorp Financial, Inc. to LeaseCorp Aviation, LLC, which was then assigned by LeaseCorp Aviation, LLC to Yingling Aircraft, Inc., as may be amended, all of which are incorporated herein by reference (together, “Master Lease 1”), covering certain aircraft hangar operation facilities located at the Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport, Wichita, Kansas, further described as Tract 1 on Exhibit “A” attached hereto and incorporated by reference, and any and all improvements now or hereafter located thereon (such land and improvements being herein referred to collectively as “Tract 1”). B. Wichita Airport Authority, Wichita, Kansas (“Lessor”) and LeaseCorp Aviation, LLC, a Kansas limited liability company, entered into that certain Master Lease Agreement dated October 14, 2014 and Supplemental Agreement No. 1 dated March 1, 2016, as may be amended, all of which are incorporated herein by reference (together, “Master Lease 2”), covering certain aircraft hangar operation facilities located at the Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport, Wichita, Kansas, further described as Tract 2 on Exhibit “A” attached hereto and incorporated by reference, and any and all improvements now or hereafter located thereon (such land and improvements being herein referred to collectively as “Tract 2”). -

Emotions and Social Movements: Twenty Years of Theory and Research

SO37CH14-Jasper ARI 1 June 2011 12:11 Emotions and Social Movements: Twenty Years of Theory and Research James M. Jasper Department of Sociology, CUNY Graduate Center, New York, NY 10016-4309; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011. 37:285–303 Keywords First published online as a Review in Advance on affective solidarity, emotional energy, emotional liberation, moral April 26, 2011 shocks, pride, shame The Annual Review of Sociology is online at soc.annualreviews.org Abstract Access provided by Harvard University on 09/16/15. For personal use only. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011.37:285-303. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org This article’s doi: The past 20 years have seen an explosion of research and theory into the 10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150015 emotions of protest and social movements. At one extreme, general the- Copyright c 2011 by Annual Reviews. oretical statements about emotions have established their importance in All rights reserved every aspect of political action. At the other, the origins and influence of 0360-0572/11/0811-0285$20.00 many specific emotions have been isolated as causal mechanisms. This article offers something in between, a typology of emotional processes aimed not only at showing that not all emotions work the same way, but also at encouraging research into how different emotions interact with one another. This should also help us overcome a residual suspicion that emotions are irrational, as well as avoid the overreaction, namely demonstrations that emotions help (and never hurt) protest mobiliza- tion and goals. 285 SO37CH14-Jasper ARI 1 June 2011 12:11 INTRODUCTION individual versus social, or affect versus emo- tion (Massumi 2002). -

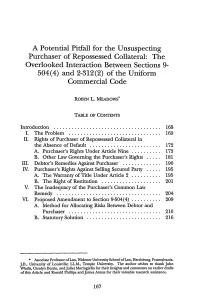

A Potential Pitfall for the Unsuspecting Purchaser of Repossessed Collateral

A Potential Pitfall for the Unsuspecting Purchaser of Repossessed Collateral: The Overlooked Interaction Between Sections 9- 504(4) and 2-312(2) of the Uniform Commercial Code ROBYN L. MEADOWS* TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . .................................... 168 I. The Problem . ............................... 169 II. Rights of Purchaser of Repossessed Collateral in the Absence of Default ........................ 172 A. Purchaser's Rights Under Article Nine .......... 173 B. Other Law Governing the Purchaser's Rights ..... 181 III. Debtor's Remedies Against Purchaser ............. 190 IV. Purchaser's Rights Against Selling Secured Party ..... 195 A. The Warranty of Title Under Article 2 .......... 195 B. The Right of Restitution .................... 201 V. The Inadequacy of the Purchaser's Common Law Remedy . ................................... 204 VI. Proposed Amendment to Section 9-504(4) .......... 209 A. Method for Allocating Risks Between Debtor and Purchaser ............................... 210 B. Statutory Solution ......................... 216 * Associate Professor of Law, Widener University School of Law, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. J.D., University of Louisville; LL.M., Temple University. The author wishes to thank John Wiadis, Carolyn Dessin, andJuliet Moringiello for their insights and comments on earlier drafts of this Article and Ronald Phillips and James Annas for their valuable research assistance. THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 44:167 INTRODUCTION Under the provisions of the Uniform Commercial Code (the Code), -

Home Equity Loans - FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

Home Equity Loans - FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS WHAT IS A HOME EQUITY LOAN? Home equity loans fall under the provisions of Section 50(a)(6), Article XVI, of the Texas Constitution. A home equity loan can be for any legal purpose which uses the equity (the difference between the home’s value and any outstanding debts against the home) in a member’s home for collateral. For home equity lending, Texas law restricts the total amount of all loans secured by the homestead to a maximum of 80% of the home’s value. Texas home equity loans can be a closed end loan with substantially equal payments over a fixed period of time, or an open end Home Equity Line of Credit (HELOC). WHAT PROPERTIES CAN BE CONSIDERED? The property used for collateral must be a single-family, owner-occupied homestead property, located within the Austin Metropolitan Statistical Area (Travis, Williamson, Hays, Bastrop and Caldwell counties). Qualifying properties are defined as either urban or rural. Urban properties consist of not more than 10 acres of land with any improvements contained thereon, within the limits of a municipality or it’s extraterritorial jurisdiction, or a platted subdivision; AND served by police protection, paid or volunteer fire protection, and at least three of the following services provided by a municipality or under contract to a municipality: electric, natural gas, sewer, storm sewer, or water. Rural property shall consist of not more than 200 acres for a family (100 acres for a single, adult person not otherwise entitled to a homestead), with the improvements thereon. -

The Aptness of Anger*

The Journal of Political Philosophy: Volume 26, Number 2, 2018, pp. 123–144 The Aptness of Anger* Amia Srinivasan Philosophy, University College London Be angry, but sin not. —Ephesians 4:26 I. In 1965, the Cambridge Union held a debate between James Baldwin and William F. Buckley Jr. on the motion ‘The American dream has been achieved at the expense of the American Negro’. Baldwin’s essay The Fire Next Time had been published two years earlier; Buckley had been editor-in-chief of the conservative magazine National Review, which he founded, for the past decade. Both men were at the height of their fame, the most important public intellectuals, respectively, in the American civil rights movement and the American conservative movement. Baldwin took the floor first, and began in a quiet, recalcitrant tone: ‘I find myself not for the first time in the position of a kind of Jeremiah’.1 He was to deliver bad news, but as history rather than prophecy: I am stating very seriously, and this is not an overstatement: that I picked the cotton, and I carried to market, and I built the railroads, under someone else’s whip, for nothing ... for nothing. The southern oligarchy which has until today so much power in Washington ... was created by my labour and my sweat, and the violation of my women and the murder of my children. This, in the land of the free and the home of the brave. And no one can challenge that statement. It is a matter of historical record. *For invaluable discussion of these issues, my thanks to Stephen Darwall, Sylvie Delacroix, Jane Friedman, John Hawthorne, Shelly Kagan, Sari Kisilevsky, Rae Langton, George Letsas, Mike Martin, Veronique Munoz-Darde, Riz Mokal, Paul Myerscough, Daniel Rothschild, Hanna Pickard, Lisa Rivera, Zofia Stemplowska, Scott Sturgeon, Zoltan Szabo, Albert Weale, Fred Wilmot-Smith, and to audiences at Birmingham, Yale, UCL, Cornell, Oxford and Cambridge. -

Foreclosing on Collateral That Includes Intangible Rights

Foreclosing on Collateral That Includes Intangible Rights JOHN I. KARESH* Table of Contents I. Introduction II. In Re Northwest Airlines Corporation 1. Court Held That Secured Party Could Not File a Proof of Claim Against Bankrupt Lessee Because Secured Party Had Not Foreclosed on Lease Rights 2. Comments on the Northwest Airlines Corporation Decision: (a) UCC Article 9 Actually Does Not Require Fore- closure for Secured Party to Enforce Assigned Lease Rights and Remedies (b) Practical Diculties in Requiring Foreclosure as a Condition to Enforcement by Secured Party of Assigned Lease Rights and Remedies III.Bremer Bank, National Association v. John Hancock Life Insurance Company et al. 1. Court Held that Early Steps Taken by Secured Party to Protect its Interests in Assigned Lease Constitute Enforcement of Remedies 2. Comments on the Bremer Decision: Why Foreclosure Was Necessary IV. Conclusion V. Appendix: Suggested Provisions to Avoid Issues Raised by the Northwest Case *John Karesh is a shareholder at Vedder Price P.C. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reect the views of Vedder Price P.C. on any of the matters addressed herein. The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Erin Zavalko-Babej, a former associate at Vedder Price P.C., in the prepara- tion of this article. 157 Uniform Commercial Code Law Journal [Vol. 42 #2] I. INTRODUCTION Issues faced by a secured party in foreclosing on its collat- eral are particularly troublesome in leveraged lease1 or other secured transactions in which the collateral includes intangibles such as the rights of a lessor under a lease of personal property and the right to le a proof of claim against a lessee that may be appropriate if the lessee les a petition for relief under the bankruptcy code, 11 U.S.C.A. -

Conventional Vs. Collateral Mortgage Charges

All our mortgage loans are secured by real property Conventional Charge: such as a house. The Bank of Nova Scotia (carrying (in Quebec, this is referred to as an “immovable on business as "Scotiabank") or Scotia Mortgage hypothec”): Corporation (SMC) will obtain mortgage security that will be registered on title against your home in the The conventional charge is granted in favour of Scotia Conventional vs. appropriate land registry office. This is referred to as Mortgage Corporation (SMC), a wholly-owned the registration of a mortgage or a "charge" and it subsidiary of Scotiabank, and is registered in first Collateral Mortgage gives Scotiabank the legal right to take action against position priority against the home. The conventional you and your home and sell it to get our money back charge covers both the land and building. Charges if you do not pay as promised or honour the terms of The specific details of the mortgage loan such as the your mortgage loan with us. amount, term, payment amount and due date and interest rate are included in the charge registered on title against your home. Collateral Charge: This conventional charge secures only the amount of The collateral charge is granted in favour of the mortgage loan. There may be costs such as legal, Scotiabank and is registered in first position priority administrative and registration costs. against the home usually for an amount that is greater than the actual amount of the mortgage loan. By registering the collateral charge for a higher Comparing Collateral Charge Mortgages -

2021 Q2 Lending and Collateral Q&A

FEDERAL HOME LOAN BANK SYSTEM Lending and Collateral Q&A August 13, 2021 Note - Each answer in this document is written as if it were a stand-alone response. Therefore, some information may be repeated. What is an advance and how do advances work? The FHLBanks provide funding to members and housing associates through secured loans known as advances. Each FHLBank makes advances based on the security of mortgage loans and other types of eligible collateral pledged by the borrowing institutions. Advances are the FHLBanks' largest asset category on a combined basis, representing 50.2% and 51.5% of combined total assets at June 30, 2021 and December 31, 2020. Advances are secured by mortgage loans held in borrower portfolios and other eligible collateral pledged by borrowers. Because members may originate loans that are not sold in the secondary mortgage market, FHLBank advances can serve as a funding source for a variety of mortgages, including those focused on very low-, low-, and moderate-income households. In addition, FHLBank advances can provide interim funding for those members that choose to sell or securitize their mortgages. Each FHLBank develops its advance programs to meet the particular needs of its borrowers, consistent with the safe and sound operation of the FHLBank. Each FHLBank offers a wide range of fixed- and variable-rate advance products with different maturities, interest rates, payment characteristics, and optionality, with maturities ranging from one day to 30 years. Who can borrow from the FHLBanks? The FHLBanks are cooperative institutions, and each FHLBank conducts its advance business almost exclusively with its members and housing associates. -

To Think...Like a CFP

FPA Journal - Best of 25 Years: To Think...Like a CFP To Think...Like a CFP by Richard B. Wagner, J.D., CFP® Editor’s note: In honor of the Journal of Financial Planning’s 25th anniversary, during 2004 we will reprint what we consider some of the best content of the Journal. This month, we present Dick Wagner’s seminal essay on the role and responsibilities of financial planners, which originally appeared in the January 1990 issue of the Journal. In this essay, the author argues that for financial planning in general, and Certified Financial Planner recipients in particular, to become accepted and respected as a real profession and as real professionals, CFP practitioners must “think” as professionals. This means developing a professional identity, a tradition, a common way planners look at themselves and at their relationships with their clients. Currently, argues the author, no such common bond exists. Furthermore, instead of being viewed as service delivery system that provides a unique and powerful role in today’s society, financial planning has been defined, by those who are not they true planners, as a “tax shelter delivery system” or a “product delivery system.” To shake these false roles and achieve a true professional identity, financial planners must develop basic financial planning theory through internal debate. At this article’s first publication, Richard B. Wagner, J.D., CFP®, was a principal with Wagner Howes Financial Inc. He now is principal of WorthLiving, LLC, in Denver, Colorado. Prologue: The students file past the ivy into the oak and dust of the ancient classroom. -

Free PDF of the Book

Children and violence Report of the Gulbenkian Foundation Commission The UK branch of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation has taken the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, ‘protecting the dignity, equality and human rights’ of children, as a broad framework within which to initiate and support specific projects of benefit to children and young people. Particular attention is given to strategic national and regional proposals which reflect the values contained in the Convention. Published by Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation London 1995 Distribution by Turnaround Distribution Ltd, 27 Horsell Road, London N5 1XL. 0171 609 7836 © 1995 Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Published by Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation 98 Portland Place, London W1N 4ET. Telephone 0171 636 5313 Designed by Susan Clarke for Expression Printers Ltd Cover design by Chris Hyde Printed by Expression Printers Ltd, London N5 1JT ISBN 0–903319–75–6 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Contents Introduction page 1 The Commission’s aims and working definitions 4 Acknowledgements 5 The Commission: members’ biographies 6 Executive summary 10 Priority recommendations 18 Section 1 Why children become violent 29 Introduction 31 Genetic factors 38 Biological factors 41 Gender 41 Conditions affecting brain function 42 Environmental or acquired biological factors 44 Brain Injury 44 Nutrition 45 Influence of the family and parenting 46 Family structure and break-up 47 Parenting styles 48 Monitoring/supervision