University Microfilms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guardian Glass Launches New Float Line at Czestochowa, Poland Plant

Contact: Sophie Weckx +352 28 111 210 [email protected] Contact: Siria Nielsen +31 164 317 036 [email protected] Guardian Glass launches new float line at Czestochowa, Poland plant New, advanced facility will serve growing Eastern Europe demand Bertrange, Luxembourg, September 22, 2020 – Guardian Glass completed its first ribbon pull at its second float glass facility in Częstochowa, Poland to help meet the growing demand for high performance coated and fabricated glass products in Poland and throughout Eastern Europe. The first pull of glass completes the plant’s startup, which began with the groundbreaking in 2018 and led to the start of the plant’s technologically advanced new glass coater on July 6. “The new float line is the largest in the Guardian family of float lines,” explains Guus Boekhoudt, Guardian Glass Executive Vice President. “We’ve implemented an innovative new furnace design with high efficiency combustion systems in order to provide products that meet the stringent quality requirements of our customers, while minimizing both the energy used for production and emissions from the process.” The plant, hosting two float lines, two coater lines and a lamination line, produces Guardian ExtraClear® float glass, Guardian ClimaGuard® low-emissivity (low-E) and Guardian SunGuard® solar control coated glass products as well as laminated glass for residential and commercial applications. By engaging suppliers to provide both proven and innovative solutions to meet production and quality requirements, Guardian Glass took a progressive approach to the design for the new float line, underlining Guardian’s long-term commitment to its customers to be the preferred supplier of glass solutions. -

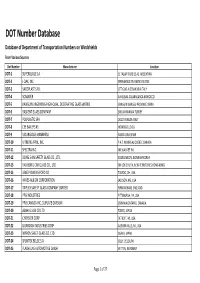

DOT Number Database Database of Department of Transportation Numbers on Windshields from Various Sources Dot Number Manufacturer Location DOT‐1 SUPERGLASS S.A

DOT Number Database Database of Department of Transportation Numbers on Windshields From Various Sources Dot Number Manufacturer Location DOT‐1 SUPERGLASS S.A. EL TALAR TIGRE BS.AS. ARGENTINA DOT‐2 J‐DAK, INC. SPRINGFIELD TN UNITED STATES DOT‐3 SACOPLAST S.R.L. OTTIGLIO ALESSANDRIA ITALY DOT‐4 SOMAVER AIN SEBAA CASABNLANCA MOROCCO DOT‐5 JIANGUIN JINGEHENG HIGH‐QUAL. DECORATING GLASS WORKS JIANGUIN JIANGSU PROVINCE CHINA DOT‐6 BASKENT GLASS COMPANY SINCAN ANKARA TURKEY DOT‐7 POLPLASTIC SPA DOLO VENEZIA ITALY DOT‐8 CEE BAILEYS #1 MONTEBELLO CA DOT‐9 VIDURGLASS MANBRESA BARCELONA SPAIN DOT‐10 VITRERIE APRIL, INC. P.A.T. MONREAL QUEBEC CANADA DOT‐11 SPECTRA INC. MILWAUKEE WI DOT‐12 DONG SHIN SAFETY GLASS CO., LTD. BOOKILMEON, JEONNAM KOREA DOT‐13 YAU BONG CAR GLASS CO., LTD. ON LOK CHUEN, NEW TERRITORIES HONG KONG DOT‐15 LIBBEY‐OWENS‐FORD CO TOLEDO, OH, USA DOT‐16 HAYES‐ALBION CORPORATION JACKSON, MS, USA DOT‐17 TRIPLEX SAFETY GLASS COMPANY LIMITED BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND DOT‐18 PPG INDUSTRIES PITTSBURGH, PA, USA DOT‐19 PPG CANADA INC.,DUPLATE DIVISION OSHAWA,ONTARIO, CANADA DOT‐20 ASAHI GLASS CO LTD TOKYO, JAPAN DOT‐21 CHRYSLER CORP DETROIT, MI, USA DOT‐22 GUARDIAN INDUSTRIES CORP AUBURN HILLS, MI, USA DOT‐23 NIPPON SHEET GLASS CO. LTD OSAKA, JAPAN DOT‐24 SPLINTEX BELGE S.A. GILLY, BELGIUM DOT‐25 FLACHGLAS AUTOMOTIVE GmbH WITTEN, GERMANY Page 1 of 27 Dot Number Manufacturer Location DOT‐26 CORNING GLASS WORKS CORNING, NY, USA DOT‐27 SEKURIT SAINT‐GOBAIN DEUTSCHLAND GMBH GERMANY DOT‐32 GLACERIES REUNIES S.A. BELGIUM DOT‐33 LAMINATED GLASS CORPORATION DETROIT, MI, USA DOT‐35 PREMIER AUTOGLASS CORPORATION LANCASTER, OH, USA DOT‐36 SOCIETA ITALIANA VETRO S.P.A. -

Alphabetical Index

Alphabetical Index 1st Source Corporation 3 Aerojet-General Corporation 12 Allied/Egry Business Systems, Inc 25 20th Century Industries 3 Aeronautical Electric Co 13 Allied Materials Corporation 26 3COM Corporation 3 Aeronca Inc 13 Allied Paper Inc 26 3M 3 Aeroquip Corporation 13 Allied Products Company 26 A A Brunell Electroplating Aerospace Corporation 13 Allied Products Corporation 26 Corporation 4 Aetna Life & Casualty Company 13 Allied Security Inc 26 A B Dick Company 4 Aetna Life Insurance & Annuity Co 13 Allied Stores Corporation 26 A C Nielsen Co 4 Aetna Life Insurance Co 14 Allied Van Lines, Inc 27 A E Staley Mfg Co 4 Affiliated Bank Corporation of Allied-Lyons North America A G Edwards Inc 4 Wyoming 14 Corporation 27 A H Belo Corporation 4 Affiliated Bankshares of Colorado 14 Allied-Signal Aerospace Company 27 A H Robins Company, Inc 4 Affiliated Food Stores, Inc 14 Allied-Signal, Inc 27 A Johnson & Company, Inc 4 Affiliated Hospital Products, Inc 14 Allis-Chalmers Corporation 28 A L Williams Corporation (The) 4 Affiliated Publications, Inc 15 Allstate Insurance Group 28 A M Castle & Co 4 AFG Industries, Inc 15 Alltel Corporation 28 A 0 Smith Corporation 4 Ag Processing Inc 15 Alma Plastics Companies 28 A P Green Refractories Co 4 Agency-Rent-A-Car Inc 15 Aloha Inc 28 A Schulman Inc 4 AGRI Industries 16 Alpha Corporation of Tennessee 28 AT Cross Co 4 AGRIPAC Inc 16 Alpha Industries Inc 28 A Y McDonald Industries, Inc 4 Ags Computers Inc 16 Alpha Metals, Inc 29 A&E Products Group, Inc 4 AGWAY Inc 16 Alpha Microsystems 29 A&M Food -

ON the SPOT... Sanjiv Gupta Sanjiv Gupta Is General Manager, Asia-Pacific at Guardian Glass

ON THE SPOT ON THE SPOT... Sanjiv Gupta Sanjiv Gupta is General Manager, Asia-Pacific at Guardian Glass. GW: What are the highlights project increased capacity, reduced so far of Guardian’s investment the company’s environmental in Thailand? footprint and added safety features. Guardian Glass’s two float glass Guardian Glass recently welcomed plants in Thailand represent more than 200 guests to a investments of approximately community and customer celebration $350 million and have a to celebrate these advances. combined production capacity of Guardian Industries President and roughly 1200 tonnes/day. They CEO, Ron Vaupel welcomed the employ 660 people. The Nong guests, including local officials and Khae facility started in 1992 dignitaries; glass dealers, fabricators, and produces clear float glass glaziers and suppliers; and company for architectural, residential, officials. The event celebrated a interior, electronics, technical successful association for more than and other glass applications, two and half decades in Thailand Left to right: Sanjiv Gupta, Montree Chanachaiviboonwat (Vice Governor, ranging in thicknesses from and our intention to strengthen the Rayong), Ron Vaupel (President and CEO, Guardian Industries) and Vigit Thongboon (Plant Manager, Rayong) at the 25th anniversary and customer 2mm to 15mm. The plant also relationship for years to come. event at Rayong. has a wet coater. The Rayong plant, which launched in 1997, GW: Following the investment, specify laminated glass for safety, sound, security and produces tinted green float glass what will Guardian’s new decorative options. for automotive and architectural production capabilities be in Both plants are also working constantly to applications. Approximately Thailand? How will your product innovate to improve operational efficiencies that will 40% of total output from these range be affected by the new enable the team to optimise the existing and new facilities is exported throughout capacity? assets. -

Party and Non-Party Political Committees Vol. IV Non-Party Detailed Tables

REPORTS ON FINANCIAL ACTIVITY 1993 - 1994 FINAL REPORT PARTY AND NON-PARTY POLITICAL COMMITTEES VOL.III - NON-PARTY DETAILED TABLES (CORPORATE AND LABOR) FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION 999 E Street, N.w. Washington, D.C. 20463 NOVEMBER 1995 FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION Danny L McDonald, Chairman Lee Ann Elliott, Vice Chairman Joan D. Aikens, Commissioner John Warren McGarry, Commissioner Trevor Potter, Chairman Scott E. Thomas, Commissioner John c. Surina, Staff Director Lawrence M. Noble, General Counsel Comments and inquiries about format should be addressed to the Reports Coordinator, Data Systems Development Division, who coordinated the production of this REPORT. Copies of 1993-1994 FINAL REPORT, PARTY AND NON-PARTY POLITICAL COMMITTEES may be obtained by writing to the Public Records Office, Federal Election Commission, 999 E Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20463. Prices are: VOL. I - $10.00, VOL. II - $10.00, VOL. III - $10.00, VOL. IV - $10.00. Checks should be made payable to the Federal Election Commission. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I DESCRIPTION OF REPORT iii II SUMMARY OF TABLES v III EXPLANATION OF COLUMNS vi IV TABLES: SELECTED FINANCIAL ACTIVITY AND ASSISTANCE TO CANDIDATES NON-PARTY POLITICAL COMMITTEES A. SELECTED FINANCIAL ACTIVITY OF CORPORATION-CONNECTED POLITICAL COMMITTEES AND THEIR ASSISTANCE TO CANDIDATES BY OFFICE AND PARTY 1 B. SELECTED FINANCIAL ACTIVITY OF LABOR ORGANIZATION CONNECTED POLITICAL COMMITTEES AND THEIR ASSISTANCE TO CANDIDATES BY OFFICE AND PARTY 439 I DESCRIPTION OF REPORT PURPOSE: This study is designed to provide information for each registered state and information on the financial transactions local major party committee, while VOLUME of Democratic, Republican, and non-party III (Corporate and Labor) and VOLUME IV political committees, with emphasis on (No Connected Organization, those transactions which support Trade/Membership/Health, Cooperative, candidates for Federal office, for the Corporation without Stock) do the same period which began on January 1, 1993. -

VISION: to Be a Trusted Global Partner Providing Reliable and Innovative Engineering Solutions That Create Superior Value for Our Customers and Society

VISION: To be a trusted global partner providing reliable and innovative engineering solutions that create superior value for our customers and society ESTABLISHED 19 5,300+ 2009 LOCATIONS EMPLOYEES SRG Global®, a Guardian company, is one of the world’s leading manufacturers of high value coatings on plastic for the automotive and commercial truck industries with a manufacturing presence in major world regions including North America, Western and Central Europe and Asia. SRG Global is headquartered in Troy, Mich., USA. Through its Research and Development Centers in Taylor, Mich, USA; Liria, Spain; Suzhou, China; and its global advanced development process, SRG Global works to enhance manufacturing processes and accelerates development and delivery of the next generation of coating technologies and subsystems. Manufacturing facility SRG Global engineers solutions for greater surface durability, structural integrity, Research & Development Center enhanced functionality, vehicle efficiency and design flexibility. The result is the Technical commercial office development of innovative exterior and interior products and processes that create value for customers and consumers and a positive impact in our environment and society. Beyond the finish™. Guardian Industries Guardian Industries, a global company headquartered in Auburn Hills, Michigan, operates facilities throughout North and South America, Europe, Africa, the Middle East and Asia. Guardian companies employ more than 14,000 people and manufacture high-performance float glass; coated and fabricated glass products for architectural, residential, interior, transportation and technical glass applications; and high-quality chrome-plated and painted plastic components for the automotive and commercial truck industries. Guardian’s vision is to be a preferred partner to our customers, suppliers, employees and communities based on a foundation of mutual CONTACT: benefit. -

Libbey-Owens-Ford Glass Company Records, 1851-1991

The Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections The University of Toledo Finding Aid Libbey-Owens-Ford Glass Company Records, 1851-1991 MSS-066 Size: 88 linear ft. Provenance: Received from Libbey-Owens-Ford Company in 1987, 1988, 1989, 1992, 1996, and 1998. Access: OPEN Collection Summary: This large collection of corporate records includes materials ranging from formal board of directors' minutes to personal photos of individuals involved with the company's history. Administrative records include corporate record books from LOF and its predecessors: Edward Ford Plate Glass Company (1899-1930), Toledo Glass Company (1895-1931), Libbey- Owens Glass Company (1916-1933), and subsidiaries. Annual reports from LOF Glass Company (1930-1982) and the Pilkington Group (1988-) provide summaries of corporate activities. Corporate file records (1895-1958) deal primarily with contracts, subsidiaries, and notably a government anti-trust investigation of LOF (1930-1948). Publications, speeches, and reports created by LOF employees and others include manuscripts and research notes from two company-sponsored corporate histories, corporate newsletters (1939-1980), and general glass industry materials. The single largest series in the collection focuses on sales and promotion. There are files on 50 distributors and dealers of LOF products across the U.S. (1930s-1970s), press releases (1946-1984), and advertising yearbooks and scrapbooks (1851-1977). "Glass at Work" files serve as a valuable source of information on the actual uses of LOF products, as well as the advertising department's use of "real life" applications for promotional purposes. They include files on glazing in everything from airports to homes (1945-1986). Subjects: Architecture, Business and Commerce and Education and Schools. -

Other State/Federal Political Action Committees Filing in Iowa

Other State/Federal Political Action Committees Filing in Iowa Committee Name Committee Number Party AT&T Inc./WarnerMedia LLC Federal Political Action 8000 Not Available Committee New Leadership for America 8001 Not Available NextEra Energy Inc. Political Action Committee 8002 Not Available Communications Workers of America Dist.7 Pol Educ. 8003 Not Available Comm. Laborers' International Union of North America Local 165 8004 Not Available DRIVE -(Democrat Republican Independent Voter 8005 Not Available Education) Citizens for Hope Responsibility Independent & Service 8006 Not Available PAC Majority in Congress 8007 Republican HDR Inc. Employee Owners PAC 8008 Not Available VoteVets.org PAC 8009 Not Available Roche Diagnostics Corporation PAC (Roche DxPAC) 8010 Not Available Penn National Gaming Inc PAC 8015 Not Available CUNA Mutual Holding Company Political Action 8016 Not Available Committee AFSCME PEOPLE 8019 Not Available Great River Area Labor Federation PAC 8020 Not Available Service Employees Intl Union Cmte. on Political 8022 Not Available Education. ( Page 1 of 270 09/28/2021 Other State/Federal Political Action Committees Filing in Iowa Resident Agent Name Agent Address Agent City State Zip Corporation Service Company 729 Insurance Exchange Building Des Moines IA 50309 Marilyn Monroe Box 6068 Des Moines IA 50309 Renee Nelson 440 W. 33rd Avenue Marion IA 52302 John Thompson 8085 East Prentice Ave. Greenwood Village CO 80111 Bonnie Eggers 5806 Meredith Dr Ste B Des Moines IA 50317 Steve Mandernach 5661 Fleur Dr Des Moines IA -

PRESS RELEASE May, 2012 Guardian Industries and Soladigm

Contacts: Amy Hennes Dan O’Mahony Guardian Industries Schwartz MSL 248-340-2109 415-512-0770 [email protected] [email protected] GUARDIAN INDUSTRIES AND SOLADIGM TO DELIVER ENERGY EFFICIENT DYNAMIC GLASS THAT “SWITCHES ON DEMAND” Collaboration to Bring Next Generation of Architectural Glass to Building Owners and Architects Auburn Hills, Mich. and Milpitas, Calif. – May 10, 2012 – Guardian Industries, one of the world's largest manufacturers of glass products, and Soladigm, a manufacturer of highly energy-efficiency dynamic glass for buildings, announced today that the companies are working together to market and sell Soladigm Dynamic Glass in the commercial buildings sector. The partnership positions Soladigm for global adoption of its dynamic glass product and provides Guardian with an innovative architectural glass technology for its customers. Guardian will incorporate Soladigm’s Dynamic Glass product into its SunGuard® advanced architectural glass portfolio of solutions with the introduction of a SunGuard EC product line. Guardian SunGuard will also integrate the new product into its Build with Light® marketing program, an initiative that connects architects, glaziers and select fabricators with its product line. Soladigm Dynamic Glass utilizes electrochromic technology to switch from clear to tinted on demand, and enables control of heat and glare in buildings while providing greater comfort, uninterrupted views, and natural daylight. Soladigm Dynamic Glass can significantly reduce heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) energy usage in commercial buildings, in particular during times of peak load. “Dynamically tinting architectural glass will substantially enhance building energy efficiency and occupant comfort. We have been carefully evaluating the landscape for the right technology that is ready for scale and wide spread adoption,” said Scott Thomsen, Guardian Glass Group president. -

ARCHITECTURAL CHALLENGES Courtesy of Guardian Glass, LLC, ©Gonzalo Botet2

ARCHITECTURAL CHALLENGES Courtesy of Guardian Glass, LLC, ©Gonzalo Botet2 Left: A rendering of ©SimpsonHaugh One Blackfriars, London Background photo: La casa del Desierto Guardian TAKING GLASS TO THE LIMITS AND BEYOND Guardian Glass’ special event for international press in London, gave invited guests the chance not only to listen to and speak with some of the company’s key people about its most recent projects, such as La Casa del Desierto and the Jeddah Tower, but also to see for themselves – One Blackfriars – which uses 5,764 panes of Guardian Glass. Glass-Technology International 5/2018 139 ARCHITECTURAL CHALLENGES uring Guardian Glass' with aesthetics – consider ian Glass, it’s important generation system and a special event held in colour for example. to know that the company set of photovoltaic panels. DLondon, members of Jasmin Hodzic, Commercial has always – and is con- Positioned in the Gorafe the press were invited to see Project Director Africa and tinuing to – make impor- Desert (Granada, Spain), for themselves how the use Middle East at Guardian tant investments. Its most considered one of the most of the company’s special Glass, gave us an overview recent investment in Eu- adverse and extreme en- glass is changing our lives. on the technical challenges rope, for example, involves vironments in Europe, La Attendees were given a pre- of megatall buildings, such a 1,000-tonne tank for Casa del Desierto stands view of one of the most re- as wind loads, temperature Poland, expected to create on a wooden structure and cent projects of Guardian and altitude differences, and 150 new jobs, thanks to the is fully glazed with high Glass – One Blackfriars – condensation. -

Guardian Glass Launches Digital Version of Its Glasstime Handbook, the “Ultimate Online Glass Knowledge Centre”

Contact: Sophie Weckx +352 28 111 210 [email protected] Contact: Siria Nielsen +31 164 317 036 [email protected] Guardian Glass launches digital version of its GlassTime handbook, the “ultimate online glass knowledge centre” Bertrange, Luxembourg, September 26, 2019 – Guardian Glass has launched a digital version of its popular GlassTime handbook, which is an outstanding tool for architects, glass processors and cladders to learn about glass and how to build with it. As a glass technical manual and encyclopedia, GlassTime is the ultimate online glass reference guide for the glass community. Previously only available in hard copy/printed format, the new digital version is interactive, easier to navigate and contains information that can be updated as needed. The content is developed by Guardian Glass experts using valuable feedback from customers and other glass influencers. The handbook is valuable for all levels of glass expertise and includes understanding the properties and benefits of glass types of glass and its use, and how it’s made. There’s also information on glass standards, as well as recommendations for glass processing and its application in a building or home. Each page of the online handbook can be printed, saved as a PDF file or shared with colleagues via email. Users can easily access the relevant Guardian Glass product pages, perform keyword searches and access useful online calculation tools such as the ‘Glass Analytics’. If users need to request a product sample, require technical support, or need specific project advice, this is just a couple of clicks away. Guus Boekhoudt, Vice President of Guardian Glass Europe, Russia and Asia & Managing Director, Guardian Europe comments: “By launching the digital version of GlassTime, Guardian Glass is providing the ultimate Glass Knowledge Centre. -

Charles Koch’S New Book — Management®, Followed by a Chapter with Communities, Employees, and Society His First in Eight Years — Will Be Released

SEPTEMBER 2015 Discovery THE QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER OF KOCH COMPANIES Re-writing the book on MBM® “Good Profit” photos by [email protected] Tuesday, Oct. 13, is an important day He also devotes a chapter to each of writes, “is to enable us to make a on Koch Industries’ corporate calendar. the five dimensions of Market-Based greater contribution to our customers, That’s when Charles Koch’s new book — Management®, followed by a chapter with communities, employees, and society his first in eight years — will be released. detailed case studies of MBM in action. as a whole. “Good Profit: How Creating Value for “Good Profit” is much more personal “That same focus will help any company Others Built One of the World’s Most than anything Charles Koch has written create good profit as well.” Successful Companies” is published by before. It includes many observations GoodProfitBook.com Penguin Random House, the world’s most about his parents, brothers, business global trade book publisher. partners and wife. But they aren’t the More than 100,000 hardback copies focus of the book. of the book were printed in mid- What he really brings to life is the way September. E-reader and audio book that Market-Based Management has versions will also be available in October. transformed the company’s approach “Good Profit” has already attracted to business in a way that helps people attention from newspapers, blogs and improve their lives. For Koch, that’s the broadcasters. That attention will likely only reason any business should exist. grow as worldwide rights are finalized — although no translations are expected to SPREADING THE NEWS be published before next year.