Baseline Archaeological Assessment & Statement Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adec Preview Generated PDF File

f An interim report on the archaeological possibilities at the site of DARLINGHURST GAOL(184I-19I2) SYDNEY,NSW by Patricia E Burritt on behalf of the Department of Public .works of the NSW Government I 27 January I981 ,I, \ I ! '~. 'I'he author "lOuld like ·to take this opportunity to thank the members of staff at the East Sydney Technical College (previously Darlinghurst Gaol) and the Mitchell Library for the willing and enthusiastic assistance that they have provided in the process of collecting information for this interim archaeological report. \ sununary of Contents Page No. I Possible benefits of archaeological investigation I 2 Background to the interim report 4 ':.,. (a) Aims of an interim archaeological report (b) Methodology employed in the preparation of this interim report on the Darlinghurst Gaol site 3 Summary of the documentary evidence examined to date 7 4 Recommendations for future archaeological work 9 !\ppendices I Chronological development of the site at Darlinghurst Gaol, according to documentary evidence . 2 Additional sources of documentary evidence ... 3 Relevant dated plans of the site (a) May I863 (Scale 50 feet to I inch) (b) March l885 (Scale l/2 inch to I foot) (c) I900 (Scale 50 feet to I inch) (d) I978 (Scale 5 metres to 9 mm) -------_.-._---- ,,-.~ -1- I possibl'e benefits of archaeological excavation Nhat is archaeology? Archaeology is an interdisciplinary subject.It is closely related to,and guided by, historical and other documentary evidence.It requires an appreciation of social and economic activities. It uses tools of analysis provided by the natural sciences. Calling upon all of these disciplines the purpose of archaeology is to discover,record and analy~e information about the activities of human beings. -

VELUX SKYLIGHTS VELUX Turns a Dark Past INTO a BRIGHT FUTURE

Sydney landmark gets VELUX SKYLIGHTS VELUX turns a dark past INTO A BRIGHT FUTURE The old Darlinghurst Gaol was converted in the early 1920s to become the East Sydney Technical College – now the National Art School. The largest building on the site, the gaol workshops, had been empty since 2005 when major renovations started in 2014. VELUX skylights were an integral part of the solution, explain CEO Michael Snelling and COO Sue Procter... Leaking roof, little light From gaol workshops to art workshops “We are the largest non-university art school in “We wanted to convert the old gaol workshops to the country and since 2005 the sole occupant modern workshops for our art students,” Michael of the old Darlinghurst Gaol site,” says Michael. continues. “At the southern end, the building was “The largest building on the campus – the old gaol used by a cooking school up until 2005 and the workshops – hadn’t been in use for almost 10 years VELUX skylights were installed where the cooking when renovations began in 2014. The building school had its ventilation shafts. Cooking needs was semiderelict with a leaking roof and very little ventilation...art needs light.” natural light...” Simple needs “We were on a tight budget but an art school’s needs are quite basic,” explains Sue. “We need open spaces, a roof that doesn’t leak, and natural light – everything else is an optional extra. So a new roof was a key part of the renovations and 80 VELUX skylights supply the natural light we require. The skylights are in a dark and dingy part of the building – getting natural light in was absolutely paramount.” < CEO Michael Snelling and COO Sue Procter Art needs NATURAL LIGHT Architect Barry McGregor has spent 35 years of his career giving new life to old buildings. -

The Economic Prison and Regional Small Business

The Economic Prison and Regional Small Business A Case Study on Kempsey and the Mid-North Coast Correctional Centre Name: Liam Frayne Number: 3061800 Advisor: Susan Thompson Photo: Liam Frayne 2006 1 Contents 1.0 Introduction 2 2.0 Prisons in Rural and Regional New South Wales 5 3.0 Regional Decline 10 4.0 The Prison Boom 18 5.0 The Role of Prisons in Regional Economic Development 26 6.0 The Impacts of the Prison as a Land Use 35 7.0 Kempsey and the Mid-North Coast Correctional Centre: 43 Background 8.0 Kempsey: On-Site Research 56 9.0 Conclusions 67 References 69 2 1.0 Introduction It is increasingly a common theme in the prison development industry in Australia and the United States for the agencies responsible for prison development to look favourably at rural and regional areas as potential sites for new correctional facilities. For the prison developer, whether Government or Private sector, locating and constructing correctional facilities in non-metropolitan regions makes sense for economic and practical reasons. Land in rural areas, particularly in economically depressed rural areas, is typically less expensive than the cost of land in cities. It is also easier in rural areas for a prison to be sited and to operate away from townships. Such a siting makes escapes and land-use conflict less likely problems for the operators of the correctional facility. The attractiveness of economically depressed non- metropolitan regions for prison development authorities has been further enhanced when many such regions actually become willing to host a correctional facility, and in many cases, are aggressively competitive with other regions in their pursuit of such a facility. -

LONG BAY: Prison, Abortion and Women of the Working Class

LONG BAY Prison, abortion and women of the working class. Eleanor Sweetapple Doctorate of Creative Arts University of Technology, Sydney 2015 ii Long Bay CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Student: Date: Long Bay iii iv Long Bay ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Rebecca’s granddaughter, Christine Jensen, for giving me her permission to fictionalise this story. Thank you for your generosity in meeting with me and sharing photographs and helping rediscover forgotten stories. Thank you as well to Annette Obree, Rebecca’s great-granddaughter, and Jan Peelgrane, Rebecca’s grandniece, for sharing family memories, photographs and documents. When I came across Rebecca Sinclair’s case I knew that I was embarking on a long and challenging project. Thank you Associate Professor Debra Adelaide for taking me on as a Doctorate of Creative Arts student at UTS and for all of your generous guidance, critique and clarity. I am also indebted to Professor Paula Hamilton, who steered me towards excellent sources of social history and asked important questions about what kind of book I wanted to write. -

1 INTRODUCTION the Australian Poet, Henry Lawson, Referred To

INTRODUCTION The Australian poet, Henry Lawson, referred to Darlinghurst Gaol in his poem “One Hundred and Three” as “Starvinghurst Goal” where prisoners were kept alone in dark cells and starved. This is the stereotype of the Victorian era gaol, whereas reality was quite different after the reforms initiated by New South Wales politician, Henry Parkes. His Select Committee of 1861 found the food in New South Wales gaols to be abundant, good and wholesome by contrast. There is also a contrasting reality for death rates in these gaols. The aim of this thesis is to show the reality of causes of death in the late Victorian era gaols by comparing the death rates and causes of death in Darlinghurst Gaol, Sydney’s main gaol from 1841 to 1914 and Auburn State Prison, the oldest existing prison in the New York State prison system, dating from 1817. Auburn Correctional Facility, as it is now known, gave its name to the “Auburn System” which included being the first institution to use separate cells for inmates, congregate work during the day, enforced silence, lockstep walking, striped uniforms and the use of the lash, or corporal punishment, as a form of punishment. It was the focus of great interest in penology and influenced the subsequent construction of many similar prisons in the USA and overseas. There has been no previous analysis of the records on the various causes of death in Victorian era gaols or the death rates in these gaols and no comparative study of gaol 1 death rates to the relevant general population to see if they were better or worse (worse being the popular perception prior to the results of the research involved in this thesis). -

Tocal's Convicts 1822-1840 Brian Patrick Walsh, B Rur Sc

Heartbreak and Hope, Deference and Defiance on the Yimmang: Tocal’s convicts 1822-1840 Brian Patrick Walsh, B Rur Sc (Hons), BA, M App Sci Ag Doctor of Philosophy University of Newcastle September 2007 This work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I hereby certify that the work embodied in this Thesis is the result of original research, the greater part of which was completed subsequent to admission to candidature for the degree. (Signed):…………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgments I wish to extend a sincere and heartfelt thanks to all who helped me during my candidature: to my supervisor, Dr Erik Eklund, for his support and guidance; to Tocal College Principal and colleague, Cameron Archer, for his unwavering enthusiasm and encouragement; to Tocal librarian, Lyn Barham, for cheerful assistance; to Jean Archer for editorial assistance and proof-reading; to David Brouwer for editorial advice; to Dean Morris for digital images; to Alberto Sega for information on James Webber in Italy; to the archivists in State Records NSW who helped me to navigate the depths of the NSW Colonial Secretary’s correspondence -

Management Plan – Cockatoo Island

The Sydney Harbour Federation Trust acknowledges the development of this Cockatoo Island Management Plan by staff at the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust, and is grateful to all those organisations and individuals who have contributed. A special thankyou is given to the members of the Community Advisory Committee and Friends of Cockatoo Island for assisting with the development of the Plan and for their invaluable comments and suggestions throughout the drafting period. Thank you also to the members of the community who attended information sessions or provided comment, and to the staff of the Department of the Environment and Energy, who made a valuable contribution to the preparation of the Plan. Authors: Staff of the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust Main Consultant Providers: Government Architect’s Office, NSW Department of Commerce Godden Mackay Logan Pty Ltd John Jeremy For full list of consultants see Related Studies section of Plan Copyright © Sydney Harbour Federation Trust 2017. This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Director Marketing, Communications & Visitor Experience Sydney Harbour Federation Trust PO Box 607, Mosman, NSW 2088 or email [email protected] For more information about the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust or to view this publication online, visit the website at: http://www.harbourtrust.gov.au 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 8 National and Commonwealth Heritage Values 73 2. Aims of this Plan 12 Condition of Values 77 3. -

LIBRARY BRUSH FARM CORRECTIVE SERVICES ACADEMY Library@CSNSW PLEASE RETURN to the LIBRARY

LIBRARY BRUSH FARM CORRECTIVE SERVICES ACADEMY Library@CSNSW PLEASE RETURN TO THE LIBRARY LONG BAY COMPLEX 1896 . 1994 A HISTORY· Final Report Terry Kass, Historian and Heritage Consultant, 32 Jellicoe Street, Lidcombe, NSW, 2141 363.69 099441 KAS tl~<;::;A Library 363.69099441 KAS 2005 2005 Long Bay complex 1896 -1994 : a history ·final report c.1 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 T 2013265 ll 1 LONG BAY Complex 1 1896- 1994 ~] A HISTORY :l FINAL Report ] :l J ' 1 I ' J Terry Kass Historian and Heritage Consultant 32 Jellicoe Street Lidcombe NSW, 2141 (02) 749 4128 ' j For NSW Public Works ' J March 1995 Long Bay Complex - History Terry Kass Final Report 2 Abbreviations A.O. Archives Office M.L. Mitchell Library PWD Public Works Department of NSW NSWPP NSW Parliamentary Papers SMH Sydney Morning Herald V. & P. L. A. N. S. W. Votes & Proceedings, Legislative Assembly, NSW DATE DUE 1-1 j__££B-20,4----- l ' l ' ' l , I • J \ 1 ·--~~' -----! . ! . j . j :J ll Long Bay Complex- History Terry Kass Final Report 3 ~ INTRODUCTION This History of the Long Bay Correctional Centre was commissioned on 19 [] December 1994 by the Public Works Department of NSW, acting for the Department of Corrective Services, as the initial stage for the preparation of a r] Conservation Plan. Many photographs taken of the Long Bay complex have not survived. Extensive searches through the Government Printer's Photograph collection and the Department of Corrective Services have not located any original photographs. ] Fortunately, some of the early reports by the Department of Prisons have excellent photographs of the complex, whilst other photographs were supplied to the press or were taken by press photographers when the male and female prisons were opened. -

Legislative Assembly

New South Wales Legislative Assembly PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Fifty-Sixth Parliament First Session Thursday, 13 October 2016 Authorised by the Parliament of New South Wales TABLE OF CONTENTS Visitors ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 VISITORS ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Bills ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 Building Professionals Amendment (Information) Bill 2016 ................................................................ 1 Education and Teaching Legislation Amendment Bill 2016 ................................................................. 1 Returned ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Documents ................................................................................................................................................. 1 Auditor-General's Report ....................................................................................................................... 1 Announcements.......................................................................................................................................... 1 Tyler Wright, Women's -

Footsteps February 2015

No. 156 ISSN 1832-9803 August 2020 SOCIETY ORGANISATION AND CONTACTS EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE President: .... Diane Gillespie ....... 0416 311 680 ..... [email protected] Vice-Pres:…. Pauline Every…….0466 988 300 …. [email protected] Treasurer: .... Clive Smith ........... 0418 206 330 ..... [email protected] Secretary: .... Jennifer Mullin ....... 0475 132 804 ..... [email protected] SUPPORT COMMITTEE Margaret Blight ...... 6583 1093 .......... [email protected] Sue Brindley ........... 0407 292 395 ..... [email protected] Anne Gaffney ......... 0408 727 [email protected] Greg Hearne ........... 0418 252 [email protected] Alastair Moss……..6584 2509…….. [email protected] AREAS OF RESPONSIBILITY ~ 2019–2020 Acquisitions/Archives………………………… ….Clive Smith Footsteps Magazine…………………………… ….Ma rgaret Blight General Meetings Roster……………………… ….Gwen Grimmond Journals…… ……………………………………… Alastair Moss/Greg Hearne Library Roster………………………………… …. .Sue Brindley Membership/Minutes…………………………… ...Jennifer Mullin Museum Heritage Group……………………... ..… Diane Gillespie InfoEmail ..... ……………………………… ...… … Diane Gillespie/Jennifer Mullin NSW & ACT Association – Delegate…… … … …. Clive Smith Publicity/Facebook………………….…….… ...…. Pauline Every Website ……………………………………… ...… Sue Brindley Public Officer……………………………… … … ...Clive Smith Research Co-Ordinator ……………………… …. .Trysha Hanley Ryerson Index Transcribers……………… .…… …. Kay and Terry Browne Social Coordinator……………………………… …Margaret Blight Welfare………………………………………… -

The Camera, the Convict and the Criminal Life1

1 ‘Through a Glass, Darkly’: the Camera, the Convict and the Criminal Life1 Julia Christabel Clark B.A. (Hons.) Thomas Fleming Taken at Port Arthur 1873-4 Photographer: probably A.H. Boyd Queen Victoria Museum & Art Gallery Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) University of Tasmania November 2015 1 ‘For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.’ 1 Corinthians 13:12, King James Bible. 2 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Julia C. Clark, 14 November 2015 3 ABSTRACT A unique series of convict portraits was created at Tasmania’s Port Arthur penal station in 1873 and 1874. While these photographs are often reproduced, their author remained unidentified, their purpose unknown. The lives of their subjects also remained unexamined. This study used government records, contemporary newspaper reportage, convict memoirs, historical research and modern criminological theory to identify the photographer, to discover the purpose and use of his work, and to develop an understanding of the criminal careers of these men. -

Extract for Those from UFP up to End of Vol 3 at 24.5.2009

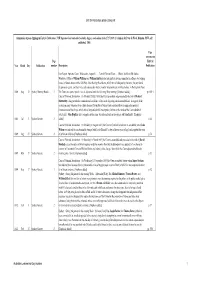

Unfit for Publication press cuttings list Summaries of press clippings in Unfit for Publication: NSW Supreme Court and other bestiality, buggery and sodomy trials 1727-1930 (3 volumes), by Peter de Waal, Balmain, NSW, self published, 2006 Page reference in Page Unfit for Year Month Day Publication number Description Publication Law Report. Supreme Court.–Wednesday, August 11. … Central Criminal Court. … (Before his Honor Mr Justice Windeyer.) Offence. William Williams and William Smith pleaded not guilty to having committed an offence at a lodging- house, in Sussex-street, on the 14th May. After hearing the evidence, which was of a disgusting character, the jury found the prisoners guilty, and they were each sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment, with hard labour, in Darlinghurst Gaol. 1800 Aug 12 Sydney Morning Herald 3 The Court, at a quarter past 6 o’clock, adjourned until the following (this) morning. [Emphasis added] pp. 650-1 Court of Criminal Jurisdiction – On Monday [25 July 1808] the Court assembled and proceeded to the trial of Richard Moxworthy, charged with the commission of an offence, of the most disgusting and abominable kind. In support of the accusation many witnesses were called, the most favourable of whom went considerable to strengthen the material circumstances of the charge; which after a long and painful investigation, left not on the minds of the Court a doubt of actual guilt. John Hopkins, his accomplice in the crime, was also indicted on the charge, and found guilty. [Emphasis 1808 Jul 31 Sydney Gazette 2 added] p. 44 Court of Criminal Jurisdiction – On Monday [21 August 1809] the Court of Criminal Jurisdiction re-assembled; when John Wilson was indicted for an abominable attempt [with Jacob (Bussell ?) a boy of eleven years of age] and acquitted for want 1809 Aug 27 Sydney Gazette 2 of sufficient evidence.