Edward Colston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bristol Open Doors Day Guide 2017

BRING ON BRISTOL’S BIGGEST BOLDEST FREE FESTIVAL EXPLORE THE CITY 7-10 SEPTEMBER 2017 WWW.BRISTOLDOORSOPENDAY.ORG.UK PRODUCED BY WELCOME PLANNING YOUR VISIT Welcome to Bristol’s annual celebration of This year our expanded festival takes place over four days, across all areas of the city. architecture, history and culture. Explore fascinating Not everything is available every day but there are a wide variety of venues and activities buildings, join guided tours, listen to inspiring talks, to choose from, whether you want to spend a morning browsing or plan a weekend and enjoy a range of creative events and activities, expedition. Please take some time to read the brochure, note the various opening times, completely free of charge. review any safety restrictions, and check which venues require pre-booking. Bristol Doors Open Days is supported by Historic England and National Lottery players through the BOOKING TICKETS Heritage Lottery Fund. It is presented in association Many of our venues are available to drop in, but for some you will need to book in advance. with Heritage Open Days, England’s largest heritage To book free tickets for venues that require pre-booking please go to our website. We are festival, which attracts over 3 million visitors unable to take bookings by telephone or email. Help with accessing the internet is available nationwide. Since 2014 Bristol Doors Open Days has from your local library, Tourist Information Centre or the Architecture Centre during gallery been co-ordinated by the Architecture Centre, an opening hours. independent charitable organisation that inspires, Ticket link: www.bristoldoorsopenday.org.uk informs and involves people in shaping better buildings and places. -

Westminster Abbey a Service for the New Parliament

St Margaret’s Church Westminster Abbey A Service for the New Parliament Wednesday 8th January 2020 9.30 am The whole of the church is served by a hearing loop. Users should turn the hearing aid to the setting marked T. Members of the congregation are kindly requested to refrain from using private cameras, video, or sound recording equipment. Please ensure that mobile telephones and other electronic devices are switched off. The service is conducted by The Very Reverend Dr David Hoyle, Dean of Westminster. The service is sung by the Choir of St Margaret’s Church, conducted by Greg Morris, Director of Music. The organ is played by Matthew Jorysz, Assistant Organist, Westminster Abbey. The organist plays: Meditation on Brother James’s Air Harold Darke (1888–1976) Dies sind die heil’gen zehn Gebot’ BWV 678 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) The Lord Speaker is received at the East Door. All stand as he is conducted to his seat, and then sit. The Speaker of the House of Commons is received at the East Door. All stand as he is conducted to his seat, and then sit. 2 O R D E R O F S E R V I C E All stand to sing THE HYMN E thou my vision, O Lord of my heart, B be all else but naught to me, save that thou art, be thou my best thought in the day and the night, both waking and sleeping, thy presence my light. Be thou my wisdom, be thou my true word, be thou ever with me, and I with thee, Lord; be thou my great Father, and I thy true son, be thou in me dwelling, and I with thee one. -

Records of Bristol Cathedral

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY’S PUBLICATIONS General Editors: MADGE DRESSER PETER FLEMING ROGER LEECH VOL. 59 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL EDITED BY JOSEPH BETTEY Published by BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 2007 1 ISBN 978 0 901538 29 1 2 © Copyright Joseph Bettey 3 4 No part of this volume may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, 5 electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other information 6 storage or retrieval system. 7 8 The Bristol Record Society acknowledges with thanks the continued support of Bristol 9 City Council, the University of the West of England, the University of Bristol, the Bristol 10 Record Office, the Bristol and West Building Society and the Society of Merchant 11 Venturers. 12 13 BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 14 President: The Lord Mayor of Bristol 15 General Editors: Madge Dresser, M.Sc., P.G.Dip RFT, FRHS 16 Peter Fleming, Ph.D. 17 Roger Leech, M.A., Ph.D., FSA, MIFA 18 Secretaries: Madge Dresser and Peter Fleming 19 Treasurer: Mr William Evans 20 21 The Society exists to encourage the preservation, study and publication of documents 22 relating to the history of Bristol, and since its foundation in 1929 has published fifty-nine 23 major volumes of historic documents concerning the city. -

Pressreader Newspaper Titles

PRESSREADER: UK & Irish newspaper titles www.edinburgh.gov.uk/pressreader NATIONAL NEWSPAPERS SCOTTISH NEWSPAPERS ENGLISH NEWSPAPERS inc… Daily Express (& Sunday Express) Airdrie & Coatbridge Advertiser Accrington Observer Daily Mail (& Mail on Sunday) Argyllshire Advertiser Aldershot News and Mail Daily Mirror (& Sunday Mirror) Ayrshire Post Birmingham Mail Daily Star (& Daily Star on Sunday) Blairgowrie Advertiser Bath Chronicles Daily Telegraph (& Sunday Telegraph) Campbelltown Courier Blackpool Gazette First News Dumfries & Galloway Standard Bristol Post iNewspaper East Kilbride News Crewe Chronicle Jewish Chronicle Edinburgh Evening News Evening Express Mann Jitt Weekly Galloway News Evening Telegraph Sunday Mail Hamilton Advertiser Evening Times Online Sunday People Paisley Daily Express Gloucestershire Echo Sunday Sun Perthshire Advertiser Halifax Courier The Guardian Rutherglen Reformer Huddersfield Daily Examiner The Independent (& Ind. on Sunday) Scotland on Sunday Kent Messenger Maidstone The Metro Scottish Daily Mail Kentish Express Ashford & District The Observer Scottish Daily Record Kentish Gazette Canterbury & Dist. IRISH & WELSH NEWSPAPERS inc.. Scottish Mail on Sunday Lancashire Evening Post London Bangor Mail Stirling Observer Liverpool Echo Belfast Telegraph Strathearn Herald Evening Standard Caernarfon Herald The Arran Banner Macclesfield Express Drogheda Independent The Courier & Advertiser (Angus & Mearns; Dundee; Northants Evening Telegraph Enniscorthy Guardian Perthshire; Fife editions) Ormskirk Advertiser Fingal -

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Colston, Edward (1636–1721) Kenneth Morgan

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Colston, Edward (1636–1721) Kenneth Morgan • Published in print: 23 September 2004 • Published online: 23 September 2004 • This version: 9th July 2020 Colston, Edward (1636–1721), merchant, slave trader, and philanthropist, was born on 2 November 1636 in Temple Street, Bristol, the eldest of probably eleven children (six boys and five girls are known) of William Colston (1608–1681), a merchant, and his wife, Sarah, née Batten (d. 1701). His father had served an apprenticeship with Richard Aldworth, one of the wealthiest Bristol merchants of the early Stuart period, and had prospered as a merchant. A royalist and an alderman, William Colston was removed from his office by order of parliament in 1645 after Prince Rupert surrendered the city to the roundhead forces. Until that point Edward Colston had been brought up in Bristol and probably at Winterbourne, south Gloucestershire, where his father had an estate. The Colston family moved to London during the English civil war. Little is known about Edward Colston's education, though it is possible that he was a private pupil at Christ's Hospital. In 1654 he was apprenticed to the London Mercers' Company for eight years. By 1672 he was shipping goods from London, and the following year he was enrolled in the Mercers' Company. He soon built up a lucrative mercantile business, trading with Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Africa. From the 1670s several of Colston’s immediate family members became involved in the Royal African Company, and Edward became a member himself on 26 March 1680. The Royal African Company was a chartered joint-stock Company based in London. -

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES © NDFHS Page 1

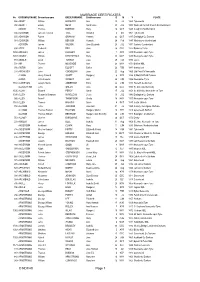

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES No GROOMSURNAME Groomforename BRIDESURNAME Brideforename D M Y PLACE 588 ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul 1869 Tynemouth 935 ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 JUL 1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16 OCT 1849 Coughton Northampton 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth 655 ADAMSON Robert GRAHAM Hannah 23 OCT 1847 Darlington Co Durham 581 ADAMSON William BENSON Hannah 24 Feb 1847 Whitehaven Cumberland ADDISON James WILSON Jane Elizabeth 23 JUL 1871 Carlisle, Cumberland 694 ADDY Frederick BELL Jane 26 DEC 1922 Barnsley Yorks 1456 AFFLECK James LUCKLEY Ann 1 APR 1839 Newcastle upon Tyne 1457 AGNEW William KIRKPATRICK Mary 30 MAY 1887 Newcastle upon Tyne 751 AINGER David TURNER Eliza 28 FEB 1870 Essex 704 AIR Thomas MCKENZIE Ann 24 MAY 1871 Belford NBL 936 AISTON John ELLIOTT Esther 26 FEB 1881 Sunderland 244 AITCHISON John COCKBURN Jane 22 Aug 1865 Utd Pres Ch Newcastle ALBION Henry Edward SCOTT Margaret 6 APR 1884 St Mark Millfield Durham ALDER John Cowens WRIGHT Ann 24 JUN 1856 Newcastle /Tyne 1160 ALDERSON Joseph Henry ANDERSON Eliza 22 JUN 1897 Heworth Co Durham ALLABURTON John GREEN Jane 24 DEC 1842 St. Giles ,Durham City 1505 ALLAN Edward PERCY Sarah 17 JUL 1854 St. Nicholas, Newcastle on Tyne 1390 ALLEN Alexander Bowman WANDLESS Jessie 10 JUL 1943 Darlington Co Durham 992 ALLEN Peter F THOMPSON Sheila 18 MAY 1957 Newcastle upon Tyne 1161 ALLEN Thomas HIGGINS Annie 4 OCT 1887 South Shields 158 ALLISON John JACKSON Jane Ann 31 Jul 1859 Colliery, Catchgate, -

Agenda Item No: 10(B)

Agenda Item No: 10(b) BEDMINSTER TOWN TEAM ANNUAL REPORT JUNE 2015 From the Chair of Bedminster Town Team Welcome to our second annual report of the BID The BID is the funding arm for Town Team activities, generated via a small levy on all eligible businesses in the area (equivalent to 1.5% of rateable value) and paid into a central ‘kitty’ to be spent on projects that benefit Bedminster businesses. Our vision remains to: Exploit and eventually explode the gap between art, advertising and entertainment, high street retailing and real estate development’ drawing on some of the lessons of Shoreditch which has reinvented itself as the UK government’s vision for the ‘largest concentration of creativity, media and technology in Europe’. This frames our priorities: • Create vibrant streets that excite and delight • Market and promote Bedminster • Reduce crime and improve the shopping environment • Advocate and lobby for Bedminster business interests • Drive down costs through joint purchasing Our numerous projects over this past twelve months have all emerged from this vision and priorities and we are delighted to see our efforts bear fruit with a continued low level of shop vacancies, some wonderful new openings – particularly on lower North Street – and announcement of major new residential developments that will provide a huge boost to trading on East St and Bedminster Parade. As you will know, the BID generates £85,000 BID income and the question of how this should be spent in Year 3 will be decided upon in open meetings for businesses on East Street, North Street and West Street throughout the summer – please do look out for these meetings (see below) and bring us your biggest and best ideas or drop us an email or give us a call – contact details on reverse. -

Guy Reid-Bailey

Guy Reid-Bailey 2:12 Biography Date of birth: 17th July 1945 Place of birth: Jamaica Guy Reid-Bailey Date of arrival in Bristol: 1961 Guy moved from Jamaica to Bristol in 1961 to live with his aunt, as his father thought that he would receive a better education in England, which they called the ‘Mother Country’. Guy was disappointed by the lack of support for Black students and the failure to Biography teach history from a Black Guy Reid-Bailey at the Bristol West Indian Cricket Club’s ground perspective. Guy had to teach himself Photo by Paul Bullivant and Tony Gill about important Black heroes like Malcolm X, Marcus Garvey, Martin Luther King and Mary Seacole. Guy’s first job was at a uniform factory called Huggins & Co in Newfoundland Road. In 1963 he applied to become a conductor with Bristol Omnibus Company but was refused an interview because he was Black. This sparked off the famous Bristol Bus Boycott, which was supported by the local African-Caribbean community, Bristol University students and Bristol East MP Tony Benn. Their campaign was successful and the bus company was forced to employ Black people. In 1964, Guy and others established the Bristol West Indian Cricket Club in Whitehall, which is now known as the Rose Green Centre. The club plays an important role in the social life of the African-Caribbean community and has a focus on developing young people. Guy remembers that in the early days, it was very difficult because many white clubs did not want to play Black teams. -

Glory Laud & Honour

A section of the Anglican Journal MAY 2018 IN THIS ISSUE Stewardship Day Telling God’s Story in Your Parish PAGES 10 – 11 Learning Party Long Long with Night of Hope Emily Scott — Year 2 PAGES 12 & 13 PAGE 9 All Glory Laud & Honour LEFT Bishop Skelton and Rev. Allan Carson prepare to take their places for the Liturgy of the Palms. RIGHT Bishop Skelton leads the Liturgy of the Palms while folks of all ages participate. As part of her 2018 episcopal visitation schedule, Bishop on March 25, 2018. It was a beautiful morning in that Melissa Skelton travelled to her parish of St. John the southeastern Fraser Valley town and the early 20th century Baptist, Sardis to join the rector, the Rev. Allan Carson and wooden church was filled to capacity. Worship began with the St. John’s community for the Palm Sunday Eucharist CONTINUED ON PAGE 2 Acolyte, Ethan waits for the procession to form behind him. Bishop Skelton speaks to the younger members of the parish about the meaning of Palm Sunday. For more Diocesan news and events visit www.vancouver.anglican.ca 2 MAY 2018 Special Synod All Glory Laud & Honour this Coming October 2018 STEPHEN MUIR, (WITH NOTES FROM GEORGE CADMAN, QC, ODNW, CHANCELLOR OF THE DIOCESE) Archdeacon of Capilano, Rector of St. Agnes, Co-chair of the Canon 2 Task Force Bishop Skelton has advised Diocesan Council, the elected and appointed governing body of the diocese that she intends to convene a Special Synod on October 13, 2018. The purpose of the Synod will be to consider changes to Canon 2, the set of rules, which govern how a bishop is elected in the diocese of New Westminster. -

The Dorcan Church

Anglican: Methodist: Diocese of Bristol Bristol District, Swindon and Marlborough Circuit _____________________________________________________________________________________ The Dorcan Church _____________________________________________________________________________________ The Dorcan Church 5-06-2013 v2 1 http://www.dorcanchurch.co.uk/ Anglican: Methodist: Diocese of Bristol Bristol District, Swindon and Marlborough Circuit _____________________________________________________________________________________ Our Mission Statement God calls us as a Church to live and share the Good News of God’s Love so that all people have the opportunity to become followers of Jesus Christ. Relying on the Holy Spirit’s Power, we commit ourselves to being open to change to make mission our top priority by: Building bridges within our local communities Offering worship that is welcoming, understandable and centered in the presence of God Building relationships where all are cared for and can grow in wholeness Making opportunities to pray regularly and together Helping people understand the Christian faith and live it Actively supporting the values of God’s kingdom: justice, reconciliation and care for people in need Who we are and what we are doing The Dorcan Church is a local Ecumenical Partnership between the Church of England and the Methodist Church serving the Swindon urban villages of Covingham, Nythe, Liden and Eldene. The partnership includes the congregation of St Paul’s Church Centre, Covingham, St Timothy’s Church, Liden and Eldene Community Centre. We are a mix of friendly, lively, all age people, that present as a ‘bag of surprises’, but needing more 20s and 30s. We need you to join with our Methodist Minister and Ministry Team to help us grow in number and engage with our local community in new ways. -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

Thrf-2019-1-Winners-V3.Pdf

TO ALL 21,100 Congratulations WINNERS Home Lottery #M13575 JohnDion Bilske Smith (#888888) JohnGeoff SmithDawes (#888888) You’ve(#105858) won a 2019 You’ve(#018199) won a 2019 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 KymJohn Tuck Smith (#121988) (#888888) JohnGraham Smith Harrison (#888888) JohnSheree Smith Horton (#888888) You’ve won the Grand Prize Home You’ve(#133706) won a 2019 You’ve(#044489) won a 2019 in Brighton and $1 Million Cash BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 GaryJohn PeacockSmith (#888888) (#119766) JohnBethany Smith Overall (#888888) JohnChristopher Smith (#888888)Rehn You’ve won a 2019 Porsche Cayenne, You’ve(#110522) won a 2019 You’ve(#132843) won a 2019 trip for 2 to Bora Bora and $250,000 Cash! BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 Holiday for Life #M13577 Cash Calendar #M13576 Richard Newson Simon Armstrong (#391397) Win(#556520) a You’ve won $200,000 in the Cash Calendar You’ve won 25 years of TICKETS Win big TICKETS holidayHolidays or $300,000 Cash STILL in$15,000 our in the Cash Cash Calendar 453321 Annette Papadulis; Dernancourt STILL every year AVAILABLE 383643 David Allan; Woodville Park 378834 Tania Seal; Wudinna AVAILABLE Calendar!373433 Graeme Blyth; Para Hills 428470 Vipul Sharma; Mawson Lakes for 25 years! 361598 Dianne Briske; Modbury Heights 307307 Peter Siatis; North Plympton 449940 Kate Brown; Hampton 409669 Victor Sigre; Henley Beach South 371447 Darryn Burdett; Hindmarsh Valley 414915 Cooper Stewart; Woodcroft 375191 Lynette Burrows; Glenelg North 450101 Filomena Tibaldi; Marden 398275 Stuart Davis; Hallett Cove 312911 Gaynor Trezona; Hallett Cove 418836 Deidre Mason; Noarlunga South 321163 Steven Vacca; Campbelltown 25 years of Holidays or $300,000 Cash $200,000 in the Cash Calendar Winner to be announced 29th March 2019 Winners to be announced 29th March 2019 Finding cures and improving care Date of Issue Home Lottery Licence #M13575 2729 FebruaryMarch 2019 2019 Cash Calendar Licence ##M13576M13576 in South Australia’s Hospitals.