A Single-Blind Randomized Comparative Study of Asafoetida Vs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herbs, Spices and Essential Oils

Printed in Austria V.05-91153—March 2006—300 Herbs, spices and essential oils Post-harvest operations in developing countries UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Telephone: (+43-1) 26026-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26926-69 UNITED NATIONS FOOD AND AGRICULTURE E-mail: [email protected], Internet: http://www.unido.org INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION OF THE ORGANIZATION UNITED NATIONS © UNIDO and FAO 2005 — First published 2005 All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to: - the Director, Agro-Industries and Sectoral Support Branch, UNIDO, Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria or by e-mail to [email protected] - the Chief, Publishing Management Service, Information Division, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to [email protected] The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization or of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Plants and Parts of Plants Used in Food Supplements: an Approach to Their

370 ANN IST SUPER SANITÀ 2010 | VOL. 46, NO. 4: 370-388 DOI: 10.4415/ANN_10_04_05 ES I Plants and parts of plants used OLOG D in food supplements: an approach ETHO to their safety assessment M (a) (b) (b) (b) D Brunella Carratù , Elena Federici , Francesca R. Gallo , Andrea Geraci , N (a) (b) (b) (a) A Marco Guidotti , Giuseppina Multari , Giovanna Palazzino and Elisabetta Sanzini (a)Dipartimento di Sanità Pubblica Veterinaria e Sicurezza Alimentare; RCH (b) A Dipartimento del Farmaco, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy ESE R Summary. In Italy most herbal products are sold as food supplements and are subject only to food law. A list of about 1200 plants authorised for use in food supplements has been compiled by the Italian Ministry of Health. In order to review and possibly improve the Ministry’s list an ad hoc working group of Istituto Superiore di Sanità was requested to provide a technical and scientific opinion on plant safety. The listed plants were evaluated on the basis of their use in food, therapeu- tic activity, human toxicity and in no-alimentary fields. Toxicity was also assessed and plant limita- tions to use in food supplements were defined. Key words: food supplements, botanicals, herbal products, safety assessment. Riassunto (Piante o parti di piante usate negli integratori alimentari: un approccio per la valutazione della loro sicurezza d’uso). In Italia i prodotti a base di piante utilizzati a scopo salutistico sono in- tegratori alimentari e pertanto devono essere commercializzati secondo le normative degli alimenti. Le piante che possono essere impiegate sono raccolte in una “lista di piante ammesse” stabilita dal Ministero della Salute. -

ASAFOETIDA (Asaf.) Botanical Name : Ferula Asafoetida Linn. Family: Umbelliferae (Apiaceae) Synonyms : F. Narthex Base, F

ASAFOETIDA (Asaf.) Botanical name : Ferula asafoetida Linn. Family: Umbelliferae (Apiaceae) Synonyms : F. narthex Base, F. persica Willd, F. foetida St., Narthex asafoetida Fale, Scordorma foetidum Bunge. Common names : Hindi: Heeng; English: Assafetida; French: Asefetide; German: Asant Stinkasant. Description : Asafoetida is an oleo-gum-resin. The gum resin is an amorphous mass. Asafoetida occurs in three forms, viz. paste, tear and mass (block or lump). Paste and tear pure forms, but bulk of the drug is mass. The tears, some of which are separate, some more or less agglutinated together, are rounded or flattened and vary from 0.5 to 4 cm in diameter. These are of a dull yellow or sometimes dingy grey colour; some darkens on keeping, finally becoming reddish-brown, but other retains their original colour for years. The red variety is derived from F. foetida and the white from F. rubricaulis (Small, 1913). When fresh they are usually tough at ordinary temperatures, becoming harder when cooled and softer when warmed. Internally they may be yellowish or milky- white, translucent or opaque; the fleshly exposed surface may gradually pass through very characteristic change of colour, becoming first pink then red and finally reddish-brown (F. foetida) or may remain nearly white (F. rubricaulis). Mass asafoetida consists of the tears agglutinated into a more or less uniform mass and mixed with varying quantities of extraneous substances such as stones, slices of the root, earthly matter, calcium carbonate and calcium sulphate etc; it is generally much inferior to the tears, the drug itself has an intense penetrating, persistent, alliaceous, odour and bitter acrid, alliaceous tests. -

Spice Aroma to Prevent Fungal Food Spoilage! Deekshitha*, Maithri P

Research & Reviews in Biotechnology & Biosciences Website: www.biotechjournal.in Research & Reviews in BiotechnologyVolume: & Biosciences 7, Issue: 1, Year: 2020 PP: 68-75ISSN No: 2321-Review8681 paper Spice aroma to prevent fungal food spoilage! Deekshitha*, Maithri P. V*, Prathika*, Shrinidhi M*, Ushalatha B*, Divya*, Yamuna*, Chandana H.C*, Archana P. P9, Bhagyashree*, Shrikavya*, Mahsoosa*,Sumangala C H1 , Bharathi Prakash2 *Students 1,2 Faculty,Department of Microbiology, University College Mangalore, Mangalore University ,Mangaluru, Karnataka Article History Abstract Received: 26/03/2020 Spices are commonly used to impart their unique aroma and taste in Revised: 06/04/2020 the food preparations. Their extracts have proved antimicrobial by Accepted: 11/04/2020 directly acting on them. The main objective of this study is to determine the antibacterial and antifungal effects of spices aroma from the distance of 2 cm and not their extracts. Aroma of 8 different Indian spices have assessed against Bacillus, Aspergillus and . DOI: Penicillium spp The spices used for this study were bought fresh http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3748482 from the local markets of Mangalore. Collected spices were clove, cumin, cinnamon, star anise, asafoetida, nutmeg and mace, pepper, carom seeds. Aroma of surface sterilized whole spices individually and in a mixture of eight was exposed to the microbes in the NA and SDA plates. The result states that cumin and clove were more effective against Bacillus than the other spices; cinnamon was more effective against Aspergillus while cinnamon and carom seeds were more effective against Penicillium. Mixture of spices was more antimicrobial than individual spices but less antibacterial and more antifungal in action. -

CALCUTTA DAL Makes ~4 Cups | 50 Minutes + Soak Time

CALCUTTA DAL Makes ~4 cups | 50 minutes + soak time A dal is simply a generic word for any split lentils, peas, or beans cooked with spices and seasonings. The type in this recipe, channa, is a split chickpea! A hearty and comforting dish that is like a blank canvas. Spice it up with your favorites. 2 cups channa dal, soaked and drained 5 cups water ¾ tsp turmeric 2 Tbsp ginger purée 1 ½ tsp salt (plus more to taste) ¾ tsp jaggery ½ Tbsp serrano purée (or minced serrano) Pop 4 Tbsp mustard oil 1 tsp cumin seeds 1 tsp mustard seeds ½ tsp fennel seeds ½ tsp kalonji seeds ¼ tsp fenugreek seeds Small pinch asafoetida 1 Tbsp kari leaves, roughly chopped instructions 1. Soak the channa dal in cold water for 2-3 hours. Drain and add 5 cups of fresh water. Bring to a boil over high heat. Lower heat, add turmeric, ginger and salt then cover and cook until tender (~40 minutes). 2. Turn off the heat & stir in jaggery & serrano purée. 3. Mix all of the spice seeds together for the pop. Heat up mustard oil and pop the cumin, mustard, fennel, kalonji, fenugreek seeds & asafoetida. After the seeds pop, turn off the heat & add the kari leaves to the hot oil. Add this to the dal and stir to combine. ideas / variations • Mix 2 parts dal with one part peanut butter and spread on toast for breakfast and top with cilantro or other herbs. • Serve with your favorite basmati rice or as an accompaniment to a salad. • No jaggery? Or asafoetida? Use honey & garlic respectively. -

SHB-Botanical-Index.Pdf

List of botanical and common names for herbs and spices copyright Ian Hemphill 2016 INDEX OF BOTANICAL NAMES OF SPICES & HERBS in The Spice & Herb Bible Third Edition by Ian Hemphill, Published by Robert Rose Inc. Canada BOTANICAL NAME FAMILY COMMONLY USED NAMES PAGE www.herbies.com.au Carum ajowan Apiaceae ajwain, bishop's weed, carum 46 Trachyspermum ammi Apiaceae ajwain, bishop's weed, carum 46 Solanum centrale Solanaceae akudjura, kutjera, bush tomato, desert raisins 52 Solanum chippendalei Solanaceae akudjura, kutjera, bush tomato, desert raisins 52 Smyrnium olusatrum Apiaceae black lovage, horse parsley, potherb, smyrnium, wild celery 57 Pimenta dioica Myrtaceae bay rum berry, clove pepper, pimento, Jamaica pepper 61 Pimenta racemosa Myrtaceae bayberry tree 61 Calycanthus floridus Myrtaceae Carolina allspice 61 Calycanthus occidentalis Myrtaceae Californian allspice 61 Mangifera indica Anacardiaceae amchur, amchoor, green mango powder 68 Angelica archangelica Apiaceae garden angelica, great angelica, holy ghost, masterwort 73 Archangelica officinalis Apiaceae garden angelica, great angelica, holy ghost, masterwort 73 Pimpenella anisum Apiaceae aniseed, anise, anise seed, sweet cumin 78 Bixa orellana Bixaceae annatto, achiote, bija, latkhan, lipstick tree, roucou 83 Ferula asafoetida Apiaceae asafoetida, asafetida, devil's dung, hing, hingra, laser 89 Melissa officinalis Lamiaceae balm, bee balm, lemon balm, melissa, sweet balm 94 Berberis vulgaris Berberidaceae barberry, holy thorn, jaundice berry, zareshk, sowberry 100 Ocimum basilicum Lumiaceae basil, sweet basil 104 Ocimum basilicum minimum Lumiaceae bush basil 104 Ocimum cannum sims Lumiaceae Thai basil 104 Page 1 of 12 List of botanical and common names for herbs and spices copyright Ian Hemphill 2016 INDEX OF BOTANICAL NAMES OF SPICES & HERBS in The Spice & Herb Bible Third Edition by Ian Hemphill, Published by Robert Rose Inc. -

Hing Processing Unit

Model Detailed Project Report HING PROCESSING UNIT Prepared by National Institute of Food Technology Entrepreneurship and Management(NIFTEM) Plot No. 97, Sector 56, HSIIDC, Industrial Estate, Kundli, Sonipat, Haryana 131028 Ministry of Food Processing Industries, Government of India 1. INTRODUCTION Asafoetida, also spelled asafetida, gets its name from the Persian aza, for mastic or resin, and the Latin foetidus, for stinking. It is a gum that is from the sap of the roots and stem of the ferula species, a giant fennel that exudes a vile odor. Asafetida is a hard-resinous gum, grayish-white when fresh, darkening with age to yellow, red and eventually brown. It is sold in blocks or pieces as a gum and more frequently as a fine yellow powder, sometimes crystalline or granulated. In its pure form, it is sold in the form of chunks of resin. The odor of the pure resin is so strong that the pungent smell will be absorbed by other spices and substances stored nearby. Hence, Asafetida has to be stores in an airtight container. The mixture is sold in sealed plastic containers with a hole that allows direct dusting of the powder. Used along with turmeric, it is a standard component of lentil curries, such as dal, curries, and vegetable dishes, especially those based on potato and cauliflower. Asafoetida is used in vegetarian Punjabi and South Indian cuisine where it enhances the flavor of numerous dishes, where it is quickly heated in hot oil before sprinkling on the food. The spice is added to the food at the time of tempering. -

The Relaxant Effect of Ferula Assafoetida on Smooth Muscles and the Possible Mechanisms

J HerbMed Pharmacol. 2015; 4(2): 40-44. Journal of HerbMed Pharmacology Journal homepage: http://www.herbmedpharmacol.com The relaxant effect of Ferula assafoetida on smooth muscles and the possible mechanisms Mohammad Reza Khazdair1, Mohammad Hossein Boskabady2* 1Pharmaciutical Research Center and Department of Physiology School of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran 2Neurogenic Inflammation Research Centre and Department of Physiology, School of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article Type: Asafoetida (Ferula asafoetida) an oleo-gum-resin belongs to the Apiaceae family which obtained Review from the living underground rhizome or tap roots of the plant. F. assa-foetida is used in traditional medicine for the treatment of variety of disorders. Asafoetida is used as a culinary spice and in Article History: folk medicine has been used to treat several diseases, including intestinal parasites, weak digestion, Received: 29 September 2014 gastrointestinal disorders, asthma and influenza. A wide range of chemical compounds including Accepted: 3 January 2015 sugars, sesquiterpene coumarins and polysulfides have been isolated from this plant. This oleo-gum- resin is known to possess antifungal, anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, anti-mutagenic and antiviral activities. Several studies investigated the effects of F. asafoetida gum extract on the contractile Keywords: responses induced by acetylcholine, methacholin, histamine and KCl on different smooth muscles. Ferula asafoetida The present review summarizes the information regarding the relaxant effect of asafetida and its Extract extracts on different smooth muscles and the possible mechanisms of this effect. -

Characterization of a Partially Purified Carom (Trachyspermum Ammi) Extract and Its Influence on Starch Functionality and Digestibility

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Characterization of a Partially Purified Carom (Trachyspermum ammi) Extract and Its Influence on Starch Functionality and Digestibility A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Food Technology (MFoodTech) at Massey University (Manawatu Campus), New Zealand Ramesh Kumar 2016 1 ABSTRACT The interactions between starches and the components in spices and herbs have been poorly studied so far. This study investigated the preliminary effects of thirty-six different spices and herbs on pasting properties of rice starch. It largely concentrated on the characterization of a partially purified carom extract (from the dried fruit of the Trachyspermum ammi plant) and its influence on the structural, thermal, pasting properties and digestibility of native rice starch. Rheology, differential scanning calorimetry, size exclusion chromatography coupled with a multi-angle laser light scattering, zeta potential, hot-stage optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and in-vitro starch digestion analysis were carried out to characterise the carom extract and starch-carom system. The results showed that carom, cumin, fennel, mulberry leaf, perilla leaf, neem and coriander seed extracts showed peak and final viscosity-suppressing effect, while mesona, rosemary, green tea, thyme, and clove extracts showed peak viscosity-enhancing effect on rice starch during starch pasting. The water-soluble fraction of carom had the highest degree of viscosity-suppressing effect as compared to other spices and herbs. -

Lead in Spices, Herbal Remedies, Ceremonial Powders, and Cosmetics

Lead in Spices, Herbal Remedies, Ceremonial Powders, and Cosmetics Some spices, herbal remedies, ceremonial powders, and cosmetics may contain lead, especially those imported from India, Asia, Mexico, and the Middle East. • Spices: Anise Seeds, Asafoetida, Chili powder/ whole chilies, Cinnamon, Cloves, Coriander, Cumin, Curry, Dagar Phool (stone flower), Garam Masala, Ginger, Hungarian Paprika, Kabsa Mix, Seven Spices Mix, and Turmeric • Herbal teas and remedies: Ash Powder, Azarcon, Balguti Kesaria, Bali Gali, Ghasard, Greta, Kandu, Mojhat ceremonial drink, and Pay-loo-ah • Ceremonial Powders: Kum kum, Incense, Pooja powder, Rangoli, and Vibuti (ash powder) • Cosmetics: Kohl, Kajal, Kum Kum, Sindoor, and Surma Lead poisoning can cause decreased IQ, attention-related deficits, hearing impairment, kidney disease, and delayed growth and development in children Spices Chili Peppers Turmeric Masala Ceremonial Powders and Cosmetics Rangoli Kum kum Sindoor Prevent Lead Poisoning • Buy spices locally rather than online or overseas. Domestic products have stricter safety standards and are more likely to have been screened for heavy metals. • Do not use products that family or friends send to you from another country. • Keep ceremonial powders and other cosmetics out of children’s reach. • Check labels of products for a state or federal agency safety label. • Take your children to the doctor’s office or local health department to have them tested for lead. NC Division of Public Health Additional Resources are available online at: 5505 Six Forks Rd Raleigh, NC 27609 http://ehs.ncpublichealth.com/hhccehb/ Phone: 919 707 5950 cehu/lead/resources.htm We would like to thank the Public Health Education students at UNC-Greensboro for providing these photographs. -

Slightly Different Foods

WELCOME TO SLIGHTLY DIFFERENT FOODS Discover our innovative range of super delicious, everyday no-fuss sauces, condiments, salad dressings, pickle & relish ABOUT US Sonia Fox-Founder • As an irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) sufferer I know what it’s like to live with gut issues and how hard it can be to find low FODMAP food products that make food delicious – that’s why Slightly Different Foods was created. An innovative solution • Slightly Different Foods sees the demand and explosion in the vegan consumer market, the increased focus on gluten and allergen free products, the issues facing individuals suffering from IBS and certain other food intolerances and we can satisfy all of these and more! Our promise • We deliver high quality food products with a clean deck of ingredients with no artificial preservatives, flavourings or colouring, lower in sugar and salt than variants, free from animal- based ingredients, Gluten Free certified, we exclude all 14 of the major allergens in all our ingredients. This enables customers to buy products that they could not consume before due to certain added ingredients. Hunters Kickin BBQ Sauce A rich and smokey BBQ sauce, great as a dip or used as a marinade. A great accompaniment to BBQ's. TYPICAL VALUES Per 100g Energy: kJ235 / Kcal: 55 Fat: 0.5g of which Saturates: 0.1g of which Monounsaturates: 0.1g of which Polyunsaturates: 0.0g Carbohydrates: 10.0g of which Sugars: 8.6g Fibre: 1.0g Protein: 1.7g Salt: 0.51g Total Fructans <0.2g GOS <0.1 Fructose 1.9g Glucose 1.7g Lactose <0.1g Mannitol <0.1g Sorbitol <0.1g INGREDIENTS: Tomatoes (tomatoes, tomato puree), Water, Cider Vinegar, Sugar, Cornflour, Black Treacle, Cocoa Powder, Asafoetida, Smoked Paprika, Salt, Smoked Water, Glucose, Chilli Powder, Black Pepper, Citric Acid. -

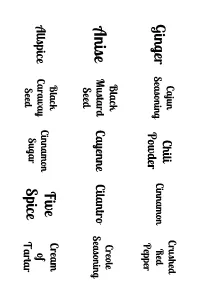

Avery Print from the Web, V5 Document

Cajun Chili Crushed Ginger Seasoning Cinnamon Red Powder Pepper Black Creole Anise Mustard Cayenne Cilantro Seasoning Seed Black Five Cream Allspice Caraway Cinnamon of Seed Sugar Spice Tartar Fenugreek Celery Basil Cloves Mace Leaves Seed Dill Garam Cardamom Coriander Thyme Weed Masala Seed Curry Fenugreek Greek Fennel Seasoning Cumin Powder Seed Seed Ras Nutmeg Parsley El Tarragon Pickling Hanout Spice Pumpkin Mustard Paprika Pie Sage Turmeric Spice Mexican Poppy Old Oregano Rosemary Oregano Seed Bay Chai Adobo Herbes Fajita Mrs. Seasoning de Seasoning Spice Province Dash Lemon Onion Minced Berbere Pepper Lavender Powder Seasoning Onion Celery Italian Garlic Taco Seasoning Savory Seasoning Salt Salt Smoked Burger Poultry Dill Bay Paprika Seasoning Seasoning Seed Leaves Beau Fish Ranch Whole Caraway Monde Seasoning Peppercorns Seed Seasoning Seasoning Apple Tandoori Steak White Pie Masala Brine Spice Rub Pepper Ancho Chile Baharat Marjoram Gochugaru Sumac Powder Sesame Saffron Za'atar Chives Lemongrass Seeds Jerk Chipotle Seasoning Chile Harissa Chervil Garlic Powder Carom Chaat Meat Achiote Mahlab Seed Masala Tenderizer Grains Nigella Fines Asafoetida of Togarashi Paradise Seed Herbes Bay Dry Nutritional Loomi Galangal Yeast Leaves Rub Dill Beef Dukkah Seed Bouillon Alum Cloves Dill Chicken Seafood Celery Truffle Pollen Bouillon Bouillon Flakes Salt Kaffir Fleur Fennel Vegetable Lime de Bouillon Annatto Pollen Leaves Sel Bay Thyme Cardamom Nutmeg Leaves Mustard Cloves Oregano Allspice Marjoram Fennel Celery Sage Coriander Anise Cumin Seed.