Abducens Nerve Palsies 2.0 Hours - COPE 69959- NO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stroke and Transient Ischaemic Attacks

53454ournal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1994;57:534-543 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.57.5.534 on 1 May 1994. Downloaded from NEUROLOGICAL MANAGEMENT Stroke and transient ischaemic attacks Peter Humphrey The management of stroke is expensive and ANATOMY accounts for about 5% of NHS hospital costs. Carotid v vertebrobasilar arterial territory Stroke is the commonest cause of severe Carotid-Classifying whether a stroke is in the physical disability. About 100 000 people territory of the carotid or vertebrobasilar suffer a first stroke each year in England and arteries is important, especially if the patient Wales. It is important to emphasise that makes a good recovery. Carotid endarterec- around 20-25% of all strokes affects people tomy is of proven value in those with carotid under 65 years of age. The annual incidence symptoms. Carotid stroke usually produces of stroke is two per 1000.' About 10% of all hemiparesis, hemisensory loss, or dysphasia. patients suffer a recurrent stroke within one Apraxia and visuospatial problems may also year. The prevalence of stroke shows that occur. If there is a severe deficit, there may there are 250 000 in England and Wales. also be an homonymous hemianopia and gaze Each year approximately 60 000 people are palsy. Episodes of amaurosis fugax or central reported to die of stroke; this represents retinal artery occlusion are also carotid about 12% of all deaths. Only ischaemic events. heart disease and cancer account for more Homer's syndrome can occur because of deaths. This means that in an "average" dis- damage to the sympathetic fibres in the trict health authority of 250 000 people, there carotid sheath. -

Clinicalguidelines

Postgrad MedJ7 1995; 71: 577-584 © The Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine, 1995 Clinical guidelines Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.71.840.577 on 1 October 1995. Downloaded from Management of transient ischaemic attacks and stroke PRD Humphrey Summary The management of stroke and transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) consumes The management of stroke and about 500 of NHS hospital costs. Stroke is the commonest cause of severe transient ischaemic attacks physical disability with an annual incidence of two per 1000.1 In an 'average' (TIAs) has changed greatly in the district general hospital of 250 000 people there will be 500 first strokes in one last two decades. The importance year with a prevalence of about 1500. TIAs are defined as acute, focal of good blood pressure control is neurological symptoms, resulting from vascular disease which resolve in less the hallmark of stroke preven- than 24 hours. The incidence of a TIA is 0.5 per 1000. tion. Large multicentre trials Stroke is not a diagnosis. It is merely a description of a symptom complex have proven beyond doubt the thought to have a vascular aetiology. It is important to classify stroke according value of aspirin in TIAs, warfarin to the anatomy ofthe lesion, its timing, aetiology and pathogenesis. This will help in patients with atrial fibrillation to decide the most appropriate management. and embolic cerebrovascular symptoms, and carotid endarter- Classification of stroke ectomy in patients with carotid TIAs. There seems little doubt Many neurologists have described erudite vascular syndromes in the past. Most that patients managed in acute ofthese are oflittle practical use. -

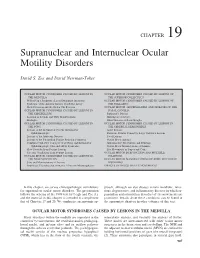

Supranuclear and Internuclear Ocular Motility Disorders

CHAPTER 19 Supranuclear and Internuclear Ocular Motility Disorders David S. Zee and David Newman-Toker OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS OF THE MEDULLA THE SUPERIOR COLLICULUS Wallenberg’s Syndrome (Lateral Medullary Infarction) OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS OF Syndrome of the Anterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery THE THALAMUS Skew Deviation and the Ocular Tilt Reaction OCULAR MOTOR ABNORMALITIES AND DISEASES OF THE OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN BASAL GANGLIA THE CEREBELLUM Parkinson’s Disease Location of Lesions and Their Manifestations Huntington’s Disease Etiologies Other Diseases of Basal Ganglia OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN THE PONS THE CEREBRAL HEMISPHERES Lesions of the Internuclear System: Internuclear Acute Lesions Ophthalmoplegia Persistent Deficits Caused by Large Unilateral Lesions Lesions of the Abducens Nucleus Focal Lesions Lesions of the Paramedian Pontine Reticular Formation Ocular Motor Apraxia Combined Unilateral Conjugate Gaze Palsy and Internuclear Abnormal Eye Movements and Dementia Ophthalmoplegia (One-and-a-Half Syndrome) Ocular Motor Manifestations of Seizures Slow Saccades from Pontine Lesions Eye Movements in Stupor and Coma Saccadic Oscillations from Pontine Lesions OCULAR MOTOR DYSFUNCTION AND MULTIPLE OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN SCLEROSIS THE MESENCEPHALON OCULAR MOTOR MANIFESTATIONS OF SOME METABOLIC Sites and Manifestations of Lesions DISORDERS Neurologic Disorders that Primarily Affect the Mesencephalon EFFECTS OF DRUGS ON EYE MOVEMENTS In this chapter, we survey clinicopathologic correlations proach, although we also discuss certain metabolic, infec- for supranuclear ocular motor disorders. The presentation tious, degenerative, and inflammatory diseases in which su- follows the schema of the 1999 text by Leigh and Zee (1), pranuclear and internuclear disorders of eye movements are and the material in this chapter is intended to complement prominent. -

A Small Dorsal Pontine Infarction Presenting with Total Gaze Palsy Including Vertical Saccades and Pursuit

Journal of Clinical Neurology / Volume 3 / December, 2007 Case Report A Small Dorsal Pontine Infarction Presenting with Total Gaze Palsy Including Vertical Saccades and Pursuit Eugene Lee, M.D., Ji Soo Kim, M.D.a, Jong Sung Kim, M.D., Ph.D., Ha Seob Song, M.D., Seung Min Kim, M.D., Sun Uk Kwon, M.D. Department of Neurology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine aDepartment of Neurology, Seoul National University, Bundang Hospital A small localized infarction in the dorsal pontine area can cause various eye-movement disturbances, such as abducens palsy, horizontal conjugate gaze palsy, internuclear ophthalmoplegia, and one-and-a-half syndrome. However, complete loss of vertical saccades and pursuit with horizontal gaze palsy has not been reported previously in a patient with a small pontine lesion. We report a 67-year-old man with a small dorsal caudal pontine infarct who exhibited total horizontal gaze palsy as well as loss of vertical saccades and pursuit. J Clin Neurol 3(4):208-211, 2007 Key Words : Ophthalmoplegia, Pontine infarction, Omnipause neurons A small localized dorsal pontine infarction can to admission he had experienced sudden general produce abducens palsy, horizontal conjugate gaze weakness for approximately 20 minutes without loss palsy, internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO), and one- of consciousness while working on his farm. The and-a-half syndrome by damaging the abducens nucleus following day, the patient experienced dysarthric and its fascicle, the paramedian pontine reticular speech and visual obscuration, and his family members formation (PPRF), or the medial longitudinal fasciculus noticed that his eyes were deviated to one side. -

GAZE and AUTONOMIC INNERVATION DISORDERS Eye64 (1)

GAZE AND AUTONOMIC INNERVATION DISORDERS Eye64 (1) Gaze and Autonomic Innervation Disorders Last updated: May 9, 2019 PUPILLARY SYNDROMES ......................................................................................................................... 1 ANISOCORIA .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Benign / Non-neurologic Anisocoria ............................................................................................... 1 Ocular Parasympathetic Syndrome, Preganglionic .......................................................................... 1 Ocular Parasympathetic Syndrome, Postganglionic ........................................................................ 2 Horner Syndrome ............................................................................................................................. 2 Etiology of Horner syndrome ................................................................................................ 2 Localizing Tests .................................................................................................................... 2 Diagnosis ............................................................................................................................... 3 Flow diagram for workup of anisocoria ........................................................................................... 3 LIGHT-NEAR DISSOCIATION ................................................................................................................. -

Supranuclear Gaze Palsy and Opsoclonus After Diazinon Poisoning T-W Liang, L J Balcer, D Solomon, S R Messé, S L Galetta

677 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.74.5.677 on 1 May 2003. Downloaded from SHORT REPORT Supranuclear gaze palsy and opsoclonus after Diazinon poisoning T-W Liang, L J Balcer, D Solomon, S R Messé, S L Galetta ............................................................................................................................. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:677–679 Brain magnetic resonance imaging was normal. Nerve con- A 52 year old man developed a supranuclear gaze palsy duction studies and EMG with repetitive stimulation were and opsoclonus after Diazinon poisoning. The diagnosis normal. Organophosphate poisoning was confirmed by low was confirmed by low plasma and red blood cell levels of plasma and red blood cell cholinesterase activity, 0.1 cholinesterase activity and urine mass spectroscopy. IU/ml (normal 5.2 to 12.8 IU/ml) and 2.2 IU/ml (normal 6.2 to Saccadic control may be mediated in part by acetylcho- 10.3 IU/ml), respectively. Treatment with atropine and line. Opsoclonus in the setting of organophosphate intoxi- pralidoxime was initiated over the next 10 days. On day 15 of cation may occur as a result of cholinergic excess which the hospital course, he became more responsive and on day 17 overactivates the fastigial nuclei. he was extubated. Neurological examination at this time showed mild diffuse weakness and tremor. His voluntary eye movements were full and his ocular flutter had resolved. His wife brought in a sample of liquid found in his garage arious central eye movement abnormalities have been which proved to be Diazinon. Diazinon was also detected in 12 described after organophosphate poisoning. -

Profile of Gaze Dysfunction Following Cerebrovascular Accident

Hindawi Publishing Corporation ISRN Ophthalmology Volume 2013, Article ID 264604, 8 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/264604 Research Article Profile of Gaze Dysfunction following Cerebrovascular Accident Fiona J. Rowe,1 David Wright,2 Darren Brand,3 Carole Jackson,4 Shirley Harrison,5 Tallat Maan,6 Claire Scott,7 Linda Vogwell,8 Sarah Peel,9 Nicola Akerman,10 Caroline Dodridge,11 Claire Howard,12 Tracey Shipman,13 Una Sperring,14 Sonia MacDiarmid,15 and Cicely Freeman16 1 Department of Health Services Research, Thompson Yates Building, University of Liverpool, Brownlow Hill, Liverpool L69 3GB, UK 2 Altnagelvin Hospitals HHS Trust, Altnagelvin BT47 6SB, UK 3 NHS Ayrshire and Arran, Ayr KA6 6DX, UK 4 Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Trust, Bath BA1 3NG, UK 5 Bury Primary Care Trust, Bury BL9 7TD, UK 6 Durham and Darlington Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Durham DH1 5TW, UK 7 Ipswich Hospital NHS Trust, Ipswich IP4 5PD, UK 8 Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Gloucester GL1 3NN, UK 9 St Helier General Hospital, Jersey JE2 3QS, UK 10University Hospital NHS Trust, Nottingham NG7 2UH, UK 11Oxford Radcliffe Hospitals NHS Trust, Oxford OX3 9DU, UK 12Salford Primary Care Trust, Salford M6 8HD, UK 13SheffieldTeachingHospitalsNHSFoundationTrust,SheffieldS102TB,UK 14Swindon and Marlborough NHS Trust, Swindon SN3 6BB, UK 15Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh NHS Trust, Wigan WN1 2NN, UK 16Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust, Worcester WR5 1DD, UK Correspondence should be addressed to Fiona J. Rowe; [email protected] Received 8 July 2013; Accepted 21 August 2013 Academic Editors: A. Daxer, R. Saxena, and I. J. Wang Copyright © 2013 Fiona J. -

Some Neuro-Ophthalmological Observations'

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.30.5.383 on 1 October 1967. Downloaded from J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiat., 1967, 30, 383 Some neuro-ophthalmological observations' C. MILLER FISHER From the Neurology Service of the Massachusetts General Hospital and the Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School This paper records some neuro-ophthalmological of 76, half hour 150, one hour 180, two hours 147 mg. 00 observations made on the Stroke Service of the The blood cholesterol was 383 mg. %. Massachusetts General Hospital. For the most part A diabetic man, age 49, had noted three months before they are not mentioned in textbooks of neurology. admission that vision in the right eye was 'broken into a jig-saw puzzle'. Everything looked gray and he saw only Although they are but minor additions to the fragments of objects here and there; e.g., in looking at clinician's fund of knowledge, their recognition may a face he saw part of an eye and a little of the mouth. One aid in accurate diagnosis. Some are possibly of month before admission vision had become worse and he interest in their own right as illustrations of the could see only from the corner of the right eye. Four integrated action of the central nervous system. months before admission at a time when vision was Since the abnormalities are generally unrelated, they intact, it had been noted that the right pupil was dilated will be discussed individually. and unreactive. Pulsation was absent on the right side in the upper extremity and in the subclavian, common carotid, Protected by copyright. -

Conjugate Gaze Palsy-The Sole Presentation of Acute Stroke

DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2018/35763.12167 Images in Medicine Conjugate Gaze Palsy-The Sole Section Presentation of Acute Stroke Internal Medicine NEERA CHAUDHRY1, KAMAKSHI DHAMIJA2, SANTOSH P KUMAR3, ASHISH KUMAR DUGGAL4, GEETA ANJUM KHWAJA5 Keywords: Foville syndrome, Paramedian pontine reticular formation, Pontine tegmentum A 45-year-old male, a known case of Type 2 diabetes mellitus and pontocerebellar fibres. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed as primary hypertension for last four years presented to the Department Foville’s syndrome [1]. of Neurology, GIPMER, New Delhi with sudden onset symptoms His routine haematological investigations were normal. The blood two weeks prior to admission in the form of imbalance while walking sugar was raised and his fasting blood sugar was 210 mg/dL and with a tendency to sway towards his left side. Along with this, he HbA1c was 6.8%. Carotid Doppler was done which revealed 30- was unable to look towards his left side. There was history of left 50% stenosis in left internal carotid artery. His echocardiography sided facial weakness in form of drooling of liquids from left angle was normal. Magnetic resonance imaging of brain showed infarct of mouth and deviation of angle of mouth towards right side while in the left inferior pontine tegmentum. There was evidence of T2/ smiling. He had no history of double vision, vertiginous sensation, FLAIR hyperintensity in the region of left inferior pontine tegmentum change in speech, tremulousness of extremities or any other motor [Table/Fig-2]. and sensory deficit. The patient was started on antiplatelets and statins. He was continued On examination, he had a blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg and on oral hypoglycaemic agents and antihypertensives. -

Vertical and Horizontal One and a Half Syndrome with Ipsiversive Ocular Tilt Reaction in Unilateral Rostral Mesencephalic Infarct: a Rare Entity

Neurology Asia 2015; 20(4) : 413 – 415 CORRESPONDENCE Vertical and horizontal one and a half syndrome with ipsiversive ocular tilt reaction in unilateral rostral mesencephalic infarct: A rare entity Supranuclear ocular movements comprise mainly vertical and horizontal movements. Vertical movements are controlled by the centres located mainly at the rostral midbrain and horizontal movements at the level of the pons.1 Pontine tegmental lesions usually present with gaze palsies, internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO), abducens palsy and one and a half syndrome. Usually, one and a half syndrome is produced by a unilateral caudal pontine tegmental lesion that includes the paramedian pontine reticular formation (PPRF) and medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF) on the same side causing horizontal gaze palsy in one eye and INO in the other eye.2 Similarly, vertical one and a half syndrome has also been described. The literature on co-existence of horizontal and vertical one and a half syndrome is few. The co-existence of horizontal and vertical one and a half syndrome with ocular tilt reaction (OTR) has not been reported so far. Here, we report a patient who presented with left horizontal one and a half syndrome along with bilateral conjugate upgaze palsy and right downward palsy suggestive of vertical one and a half syndrome and left ocular tilt reaction. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain revealed infarct in left rostral midbrain with sparing of pons. A 64-year-old male was brought with history of giddiness, weakness of right upper limb and double vision on looking to the left of 7 days duration. The symptoms were sudden in onset and persistent. -

DOUBLE TROUBLE ACQUIRED DIPLOPIA in ADULTS Matthew Mahek, OD DOUBLE TROUBLE

2020 Clinical Optometry Update and Review DOUBLE TROUBLE ACQUIRED DIPLOPIA IN ADULTS Matthew Mahek, OD DOUBLE TROUBLE • No financial disclosures DOUBLE TROUBLE • Objectives: • Discuss the most common causes of acquired diplopia in adults • Review the management of these patients presenting with diplopia • Review the indications for further systemic workup DOUBLE TROUBLE WHERE TO START CC: Double vision 1st Question: Does it go away with one eye covered? • Yes: Binocular diplopia • No: Monocular diplopia DOUBLE TROUBLE WHERE TO START Monocular Diplopia Binocular Diplopia • Refractive • Optical • Optical • CNS • Retinal • Orbital • Systemic • Binocular Vision Disorders MONOCULAR DIPLOPIA ETIOLOGY • Refractive • Optical • Retinal MONOCULAR DIPLOPIA WHERE TO START CC: Double vision 1. Does it go away when you cover one eye? • No (monocular) 2. Right, Left, both eyes? 3. Constant or intermittent? MONOCULAR DIPLOPIA ETIOLOGY • Refractive • Optical • Retinal MONOCULAR DIPLOPIA REFRACTIVE • Uncorrected refractive error • Regular astigmatism • Anisometropia • Irregular astigmatism • Diagnostic RGP • Exam • Refraction • Topography MONOCULAR DIPLOPIA ETIOLOGY • Refractive • Optical • Retinal MONOCULAR DIPLOPIA • Optical Irregularities • Dry eye • Intermittent • Corneal Opacities • Diagnostic RGP • Iris/pupil • Cosmetic contact lens • Cataract MONOCULAR DIPLOPIA ETIOLOGY • Refractive • Optical • Retinal MONOCULAR DIPLOPIA • Retina • Macular Edema • Central Serous • Exudative ARMD DOUBLE TROUBLE CC: Double vision 1st Question: Does it go away with -

Paralytic Strabismus: Third, Fourth, and Sixth Nerve Palsy

Paralytic Strabismus: Third, Fourth, and Sixth Nerve Palsy a, b Sashank Prasad, MD *, Nicholas J. Volpe, MD KEYWORDS Paralytic strabismus Nerve palsy Ocular motor nerves Eye movement abnormalities ANATOMY Eye movements are subserved by the ocular motor nerves (cranial nerves 3, 4, and 6), which innervate the 6 extraocular muscles of each eye (Fig. 1). The oculomotor (third) nerve innervates the medial rectus, inferior rectus, superior rectus, and inferior oblique muscles, as well as the levator palpebrae. The trochlear (fourth) nerve innervates the superior oblique muscle, and the abducens (sixth) nerve innervates the lateral rectus muscle. The nuclear complex of the third nerve lies in the dorsal midbrain, anterior to the cerebral aqueduct. It consists of multiple subnuclei that give rise to distinct sets of fibers destined for the muscles targeted by the third nerve. In general, the axons arising from these subnuclei travel in the ipsilateral nerve, except axons arising from the superior rectus subnucleus that travel through the contralateral third nerve complex to join the third nerve on that side.1 In addition, a single central caudate nucleus issues fibers that join both third nerves to innervate the levator palpebrae muscles bilaterally.2 The preganglionic cholinergic fibers that innervate the pupillary constrictor arise from the paired Edinger-Westphal nuclei. On exiting the nuclear complex, the third nerve fascicles travel ventrally, traversing the red nucleus and the cerebral peduncles, before exiting the midbrain into the interpeduncular fossa. The proximal portion of the nerve passes between the superior cerebellar and poste- rior cerebral arteries.3 The axons are topographically arranged, with fibers for the infe- rior rectus, medial rectus, superior rectus, and inferior oblique arranged along the Dr Prasad is supported by a Clinical Research Training Grant from the American Academy of Neurology.