Economic Regulation and Its Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glenn Reitmeier Component Digital Video Interface Now by the Time Testing Was Completed, All Used Worldwide

IGNITING CHANGE of a job that would allow Reitmeier to ing would determine the winner. Sarnoff “y I can’t sa enough apply advanced signal processing to TV. couldn’t pass up the challenge. Sarnoff also would send him to the Uni- An early prophet of digital TV, about the personal versity of Pennsylvania for his master’s. Reitmeier was tapped to lead the devel- attention of the Villanovans contributing to the community Reitmeier hit the ground digitizing. He opment of the Advanced Digital HDTV helped develop the architecture and soft- system for Sarnoff and its consortium faculty and their ware for one of the first computer systems partners: Philips, Thomson and NBC. dedication to for digitizing video; picked up his first pat- Competing against the calendar and new ent for picture resizing for digital video digital approaches from such titans as teaching.” effects; and contributed to experiments AT&T and MIT, Reitmeier’s team worked that led to the adoption of a standard for feverishly to build their prototype. — Glenn Reitmeier component digital video interface now By the time testing was completed, all used worldwide. This pace never slack- analog proposals had been eliminated, ened in Reitmeier’s 25 years at Sarnoff. since they couldn’t send HDTV in a single His collaboration and leadership in digi- over-the-air TV channel. But surprisingly, Their achievement earned the Grand tal video research, consumer electronics none of the four digital entries was victori- Alliance companies an Emmy Award. and other technologies earned Reitmeier ous. Each had strengths and weaknesses. Since 2002, Reitmeier has guided NBC the industry’s respect—and his children’s. -

The Magnificent Seven: American Telephony's Deregulatory Shootout, 50 Hastings L.J

Hastings Law Journal Volume 50 | Issue 6 Article 5 1-1999 The aM gnificent Seven: American Telephony's Deregulatory Shootout Jim Chen Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jim Chen, The Magnificent Seven: American Telephony's Deregulatory Shootout, 50 Hastings L.J. 1503 (1999). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol50/iss6/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. The Magnificent Seven: American Telephony's Deregulatory Shootout by JIM CHEN* Table of Contents I. High N oon .................................................................................. 1504 II. The Gunslingers, Then and Now ...................... 1506 A. The Opening Round ........................................................... 1507 B. The Magnificent Seven ...................................................... 1511 (1) POTS and PANS, Hedgehogs and Foxes ................... 1511 (2) Lord Low Everything Else ................. 1513 III. The Legal Mothers of Merger Mania ...................................... 1514 A. Statutory Starters .............. ............ 1515 (1) Section 251 and Allied Provisions ............................... 1516 (2) Section 271: BOC Entry into InterLATA Carriage .1519 * Professor of Law and Vance K. Opperman Research -

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Department of Telecommunications and Energy Cable Television Division

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF TELECOMMUNICATIONS AND ENERGY CABLE TELEVISION DIVISION MediaOne of Massachusetts, Inc., MediaOne Group, Inc., and AT&T Corp., Appellants, v. CTV 99-2 Board of Selectmen of the Town of North Andover, Appellee. OPPOSITION OF TOWN OF NORTH ANDOVER TO MOTION FOR EXPEDITED PROCESSING OF APPEAL The Town of North Andover ("North Andover") opposes the motion of MediaOne of Massachusetts, Inc, MediaOne Group, Inc., and AT&T Corp. (collectively, “Appellants”) to expedite the hearing or processing of this matter. For the reasons set forth below, the Massachusetts Department of Telecommunication and Energy, Cable Television Division (the "Division"), should deny the Appellants’ motion to expedite this proceeding and should schedule this matter for a full evidentiary hearing, giving appropriate consideration to the complex legal and factual matters at issue in the case. I. Introduction North Andover has moved that the Division consolidate any and all hearings with respect to the review of decisions by North Andover (CTV 99-2), Cambridge (CTV 99-4), Quincy (CTV 99-3) and Somerville (CTV 99-5) to deny or to conditionally approve the transfer of cable licenses from MediaOne Group, Inc. ("MediaOne") to AT&T Corp. ("AT&T") pursuant to M.G.L. c. 166A §7 and applicable regulations. Each of the decisions has as a common requirement that AT&T provide open or nondiscriminatory access to cable broadband for Internet and on-line services. The open access requirement, which preserves consumer choice and preserves competition among Internet and on-line service providers, should be reviewed by the Division in a consolidated evidentiary hearing that will allow for a complete and efficient presentation of this critical public policy question. -

Competition in Local Broadcast Television Advertising Markets Kevin Caves and Hal Singer August 4, 2014

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) 2014 Quadrennial Regulatory Review – Review ) MB Docket No. 14-50 of the Commission’s Broadcast Ownership Rules ) and Other Rules Adopted Pursuant to Section ) 202 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) ) 2010 Quadrennial Regulatory Review – Review ) MB Docket No. 09-182 of the Commission’s Broadcast Ownership Rules ) and Other Rules Adopted Pursuant to Section ) 202 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) ) Promoting Diversification of Ownership ) MB Docket No. 07-294 in the Broadcasting Services ) ) Rules and Policies Concerning ) MB Docket No. 04-256 Attribution of Joint Sales Agreements ) in Local Television Markets ) ) Competition in Local Broadcast Television Advertising Markets Kevin Caves and Hal Singer August 4, 2014 -2- Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 I. Background ......................................................................................................................... 4 A. The DOJ Asserts That Local Broadcast Television Advertising Is a Relevant Antitrust Product Market ........................................................................................ 4 B. The DOJ’s Position Lacks Empirical Support ........................................................ 5 II. Empirical Evidence Is Inconsistent with the DOJ’s Definition of the Relevant Product Market ................................................................................................................................ -

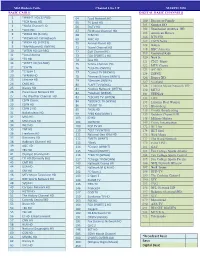

2020 March Channel Line up with Pricing Color

B is Mid-Hudson Cable Channel Line UP MARCH 2020 BASIC CABLE DIGITAL BASIC CHANNELS 2 *WMHT HD (17 PBS) 64 Food Network HD 100 Discovery Family 3 *FOX News HD 65 TV Land HD 101 Science HD 4 *NASA Channel HD 66 TruTV HD 102 Destination America HD 5 *QVC HD 67 FX Movie Channe l HD 105 American Heroes 6 *WRGB HD (6-CBS) 68 TCM HD 106 BTN HD 7 *WCWN HD CW Network 69 AMC HD 107 ESPN News 8 *WXXA HD (FOX23) 70 Animal Planet HD 108 Babytv 9 *My4AlbanyHD (WNYA) 71 Travel Channel HD 118 BBC America 10 *WTEN HD (10-ABC) 72 Golf Channel HD 119 Universal Kids 11 *Local Access 73 FOX SPORTS 1 HD 12 *FX HD 120 Nick Jr. 74 fuse HD 121 CMT Music 13 *WNYT HD (13-NBC) 75 Tennis Channel HD 122 MTV Classic 17 *EWTN 76 *LIGHTtv (WNYA) 123 IFC HD 19 *C-Span 1 77 *Comet TV (WCWN) 124 ESPNU 20 *WRNN HD 78 *Heroes & Icons (WNYT) 126 Disney XD 23 Lifetime HD 79 *Decades (WNYA) 127 Viceland 24 CNBC HD 80 *LAFF TV (WXXA) 128 Lifetime Movie Network HD 25 Disney HD 81 *Justice Network (WTEN) 130 MTV2 26 Paramount Network HD 82 *Stadium (WRGB) 131 TEENick 27 The Weather Channel HD 83 *ESCAPE TV (WTEN) 132 LIFE 28 ESPN Classic 84 *BOUNCE TV (WXXA) 133 Lifetime Real Women 29 ESPN HD 86 *START TV 135 Bloomberg 30 ESPN 2 HD 95 *HSN HD 138 Trinity Broadcasting 31 Nickelodeon HD 99 *PBS Kids(WMHT) 139 Outdoor Channel HD 32 MSG HD 103 ID HD 148 Military History 33 MSG PLUS HD 104 OWN HD 149 Crime Investigation 34 WE! HD 109 POP TV HD 172 BET her 35 TNT HD 110 *GET TV (WTEN) 174 BET Soul 36 Freeform HD 111 National Geo Wild HD 175 Nick Music 37 Discovery HD 112 *METV (WNYT) -

Are You Ready for Digital TV? 20 January 2009

Are you ready for digital TV? 20 January 2009 (PhysOrg.com) -- If everything goes as planned, on Q: If I install a digital converter box to my Feb. 17 the long-awaited switch from analog to television set, what will I get? digital broadcasting will take place and millions of DS: Provided that the digital converter box has a analog television sets across the nation will go reasonably good antenna, you would be able to black. Temple University electrical and computer receive the over-the-air digital signals that the engineering Professor Dennis Silage, an expert in broadcasters are transmitting; basically, your local both analog and digital communications, has television stations. You have to hook the converter answered some questions about this digital TV box up to an antenna and even a simple a ‘rabbit transition and what it will mean for consumers. ear’ antenna may work for you. We’re going back to the future, if you remember when you used to Q: Why are we switching from analog? have rabbit ear antennas on your TV and you had DS: Analog is a 60-plus-year-old technology that to play around with them to get the best picture. has basically lasted the test of time, but doesn’t Now, because of the digital conversion, your local really allow more advanced services, such as television stations also have subsidiary channels additional channels and information using the that would be very interesting to see. They may existing the broadcast spectrum. It’s not as have as many as three subsidiary channels. -

Broadcasting & Convergence

1 Namnlöst-2 1 2007-09-24, 09:15 Nordicom Provides Information about Media and Communication Research Nordicom’s overriding goal and purpose is to make the media and communication research undertaken in the Nordic countries – Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden – known, both throughout and far beyond our part of the world. Toward this end we use a variety of channels to reach researchers, students, decision-makers, media practitioners, journalists, information officers, teachers, and interested members of the general public. Nordicom works to establish and strengthen links between the Nordic research community and colleagues in all parts of the world, both through information and by linking individual researchers, research groups and institutions. Nordicom documents media trends in the Nordic countries. Our joint Nordic information service addresses users throughout our region, in Europe and further afield. The production of comparative media statistics forms the core of this service. Nordicom has been commissioned by UNESCO and the Swedish Government to operate The Unesco International Clearinghouse on Children, Youth and Media, whose aim it is to keep users around the world abreast of current research findings and insights in this area. An institution of the Nordic Council of Ministers, Nordicom operates at both national and regional levels. National Nordicom documentation centres are attached to the universities in Aarhus, Denmark; Tampere, Finland; Reykjavik, Iceland; Bergen, Norway; and Göteborg, Sweden. NORDICOM Göteborg -

US V. AT&T Corp. and Mediaone Group, Inc

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) United States of America ) Antitrust Division ) Department ofJustice ) 1:oocvo111G CASE NUMBER 140 I H Street ) c. Lamberth Washington, D.C. 20530, ) JUDGE: Royce Plaintiff, ) Antitrust ) DECK TYPE: v. ) os12s12000 DATE STAMP: ) AT&T Corp. and ) MediaOne Group, Inc., ) Defendants. ) COMPLAINT The United States of America, acting under the direction ofthe Attorney General ofthe United States, brings this civil action pursuant to Section 15 of the Clayton Act, as amended, 15 U.S.C. § 25, to enjoin defendant AT&T Corp. ("AT&T") from acquiring defendant MediaOne Group, Inc. ("MediaOne"), in order to prevent and restrain a violation of Section 7 of the Clayton Act, as amended, 15 U.S.C. § 18. Unless blocked, AT&T's acquisition of MediaOne's interest is likely to lessen competition substantially in the market for the aggregation, promotion, and distribution of broadband content. Road Runner is an Internet service provider that offers high-speed access to content through cable lines nationwide. Broadband service is technology that allows users to -1 used telephone dial-up services. Road Runner competes with Excite@Home, in which AT&T " - owns a substantial equity interest and voting control, in aggregating, promoting and distributing broadband content. MediaOne holds a significant equity and management interest in Road Runner. Excite@Home and Road Runner serve a significant majority of the nation's residential broadband Internet users. Through the proposed merger, concentration in the market for aggregation, promotion, and distribution of residential broadband content would be substantially increased. Competition between Excite@Home and Road Runner in the provision of these services may be substantially lessened or even eliminated. -

CPUC Data Request FCC Form 477

FIGURE G1: LIST OF CARRIERS SAMPLED VIA CPUC DATA REQUEST CPUC Data Request FCC Form 477 ILECs Included ILECs Included Citizens Telecommunications Company of Citizens Telecommunications Company California, Inc. of California Pacific Bell Pacific Bell Roseville Telephone Company Roseville Telephone Company Verizon California, Inc.(formerly GTE Verizon California, Inc.(formerly GTE California) California) Evans Telephone Company Kerman Telephone Co. Pinnacles Telephone Company Sierra Telephone Company Volcano Telephone Company CLECs/ IXCs Included CLECs Included AT&T Communications of California, Inc. AT&T Corp. Cox California Telecom, LLC Cox Communications Pac-West Telecommunications, Inc. ---------- Sprint Communications Company, L.P. Sprint Corporation Worldcom, Inc. MCI WorldCom, Inc./ WorldCom Inc. Adelphia Communications Corporation Advanced TelCom, Inc. Allegiance Telecom of California, Inc. AOL Time Warner/ Time Warner Cable/ Time Warner Communications Broadwing Communications Inc. Charter Communications Comcast Corporation/ Comcast Cable Communications, Inc. Focal Communications Corporation of California GST Telecom, Inc. ICG Telecom Group, Inc. Intermedia Communications Inc. Mediacom California LLC MediaOne Group, Inc. MGC Communications/ Mpower Communications Nextlink California, Inc./ XO California, Inc. Pacific Bell Company/ Pacific Bell Services [CLEC] RCN Telecom Services of CA, Inc. Seren Innovations Siskiyou Cablevision, Inc. Teligent Services, Inc. Qwest Interprise America, Inc. U.S. Telepacific Corp dba Telepacific Communications -

ATSC Standard: Program and System Information Protocol for Terrestrial Broadcast and Cable (Revision C) with Amendment No

A/65C 2 January 2006 Amendment No. 1 dated 9 May 2006 ATSC Standard: Program and System Information Protocol for Terrestrial Broadcast and Cable (Revision C) With Amendment No. 1 Advanced Television Systems Committee 1750 K Street, N.W. Suite 1200 Washington, D.C. 20006 http://www.atsc.org ATSC A/65C Program and System Information Protocol 2 January 2006 The Advanced Television Systems Committee, Inc., is an international, non-profit organization developing voluntary standards for digital television. The ATSC member organizations represent the broadcast, broadcast equipment, motion picture, consumer electronics, computer, cable, satellite, and semiconductor industries. Specifically, ATSC is working to coordinate television standards among different communications media focusing on digital television, interactive systems, and broadband multimedia communications. ATSC is also developing digital television implementation strategies and presenting educational seminars on the ATSC standards. ATSC was formed in 1982 by the member organizations of the Joint Committee on InterSociety Coordination (JCIC): the Electronic Industries Association (EIA), the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE), the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB), the National Cable Television Association (NCTA), and the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE). Currently, there are approximately 140 members representing the broadcast, broadcast equipment, motion picture, consumer electronics, computer, cable, satellite, and semiconductor industries. ATSC Digital TV Standards include digital high definition television (HDTV), standard definition television (SDTV), data broadcasting, multichannel surround-sound audio, and satellite direct-to-home broadcasting. NOTE: The user's attention is called to the possibility that compliance with this standard may require use of an invention covered by patent rights. By publication of this standard, no position is taken with respect to the validity of this claim or of any patent rights in connection therewith. -

Program and System Information Protocol Implementation Guidelines for Broadcasters

ATSC Recommended Practice: Program and System Information Protocol Implementation Guidelines for Broadcasters Document A/69:2009, 25 December 2009 Advanced Television Systems Committee, Inc. 1776 K Street, N.W., Suite 200 Washington, D.C. 20006 Advanced Television Systems Committee Document A/69:2009 The Advanced Television Systems Committee, Inc., is an international, non-profit organization developing voluntary standards for digital television. The ATSC member organizations represent the broadcast, broadcast equipment, motion picture, consumer electronics, computer, cable, satellite, and semiconductor industries. Specifically, ATSC is working to coordinate television standards among different communications media focusing on digital television, interactive systems, and broadband multimedia communications. ATSC is also developing digital television implementation strategies and presenting educational seminars on the ATSC standards. ATSC was formed in 1982 by the member organizations of the Joint Committee on InterSociety Coordination (JCIC): the Electronic Industries Association (EIA), the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE), the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB), the National Cable Telecommunications Association (NCTA), and the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE). Currently, there are approximately 140 members representing the broadcast, broadcast equipment, motion picture, consumer electronics, computer, cable, satellite, and semiconductor industries. ATSC Digital TV Standards include -

Fcc Written Response to the Gao Report on Dtv Table of Contents

FCC WRITTEN RESPONSE TO THE GAO REPORT ON DTV TABLE OF CONTENTS I. TECHNICAL GOALS 1. Develop Technical Standard for Digital Broadcast Operations……………………… 1 2. Pre-Transition Channel Assignments/Allotments……………………………………. 5 3. Construction of Pre-Transition DTV Facilities……………………………………… 10 4. Transition Broadcast Stations to Final Digital Operations………………………….. 16 5. Facilitate the production of set top boxes and other devices that can receive digital broadcast signals in connection with subscription services………………….. 24 6. Facilitate the production of television sets and other devices that can receive digital broadcast signals……………………………………………………………… 29 II. POLICY GOALS 1. Protect MVPD Subscribers in their Ability to Continue Watching their Local Broadcast Stations After the Digital Transition……………………………….. 37 2. Maximize Consumer Benefits of the Digital Transition……………………………... 42 3. Educate consumers about the DTV transition……………………………………….. 48 4. Identify public interest opportunities afforded by digital transition…………………. 53 III. CONSUMER OUTREACH GOALS 1. Prepare and Distribute Publications to Consumers and News Media………………. 59 2. Participate in Events and Conferences……………………………………………… 60 3. Coordinate with Federal, State and local Entities and Community Stakeholders…… 62 4. Utilize the Commission’s Advisory Committees to Help Identify Effective Strategies for Promoting Consumer Awareness…………………………………….. 63 5. Maintain and Expand Information and Resources Available via the Internet………. 63 IV. OTHER CRITICAL ELEMENTS 1. Transition TV stations in the cross-border areas from analog to digital broadcasting by February 17, 2009………………………………………………………………… 70 2. Promote Consumer Awareness of NTIA’s Digital-to-Analog Converter Box Coupon Program………………………………………………………………………72 I. TECHNICAL GOALS General Overview of Technical Goals: One of the most important responsibilities of the Commission, with respect to the nation’s transition to digital television, has been to shepherd the transformation of television stations from analog broadcasting to digital broadcasting.