Subspecific Identification of the Willet Catoptrophorus Semipalmatus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long-Billed Curlew Distributions in Intertidal Habitats: Scale-Dependent Patterns Ryan L

LONG-BILLED CURLEW DISTRIBUTIONS IN INTERTIDAL HABITATS: SCALE-DEPENDENT PATTERNS RYAN L. MATHIS, Department of Wildlife, Humboldt State University, Arcata, Cali- fornia 95521 (current address: National Wild Turkey Federation, P. O. Box 1050, Arcata, California 95518) MARK A. ColwELL, Department of Wildlife, Humboldt State University, Arcata, California 95521; [email protected] LINDA W. LEEMAN, Department of Wildlife, Humboldt State University, Arcata, California 95521 (current address: EDAW, Inc., 2022 J. St., Sacramento, California 95814) THOMAS S. LEEMAN, Department of Wildlife, Humboldt State University, Arcata, California 95521 (current address: Environmental Science Associates, 8950 Cal Center Drive, Suite 300, Sacramento, California 95826) ABSTRACT. Key ecological insights come from understanding a species’ distribu- tion, especially across several spatial scales. We studied the distribution (uniform, random, or aggregated) at low tide of nonbreeding Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) at three spatial scales: within individual territories (1–8 ha), in the Elk River estuary (~50 ha), and across tidal habitats of Humboldt Bay (62 km2), Cali- fornia. During six baywide surveys, 200–300 Long-billed Curlews were aggregated consistently in certain areas and were absent from others, suggesting that foraging habitats varied in quality. In the Elk River estuary, distributions were often (73%) uniform as curlews foraged at low tide, although patterns tended toward random (27%) when more curlews were present during late summer and autumn. Patterns of predominantly uniform distribution across the estuary were a consequence of ter- ritoriality. Within territories, eight Long-billed Curlews most often (75%) foraged in a manner that produced a uniform distribution; patterns tended toward random (16%) and aggregated (8%) when individuals moved over larger areas. -

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List The target species list (species to be surveyed) should not change over the course of the study, therefore determining the target species list is an important project design task. Because waterbirds, including shorebirds, can occur in very high numbers in a census area, it is often not possible to count all species without compromising the quality of the survey data. For the basic shorebird census program (protocol 1), we recommend counting all shorebirds (sub-Order Charadrii), all raptors (hawks, falcons, owls, etc.), Common Ravens, and American Crows. This list of species is available on our field data forms, which can be downloaded from this site, and as a drop-down list on our online data entry form. If a very rare species occurs on a shorebird area survey, the species will need to be submitted with good documentation as a narrative note with the survey data. Project goals that could preclude counting all species include surveys designed to search for color-marked birds or post- breeding season counts of age-classed bird to obtain age ratios for a species. When conducting a census, you should identify as many of the shorebirds as possible to species; sometimes, however, this is not possible. For example, dowitchers often cannot be separated under censuses conditions, and at a distance or under poor lighting, it may not be possible to distinguish some species such as small Calidris sandpipers. We have provided codes for species combinations that commonly are reported on censuses. Combined codes are still species-specific and you should use the code that provides as much information as possible about the potential species combination you designate. -

The All-Bird Bulletin

Advancing Integrated Bird Conservation in North America Spring 2014 Inside this issue: The All-Bird Bulletin Protecting Habitat for 4 the Buff-breasted Sandpiper in Bolivia The Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Conserving the “Jewels 6 Act (NMBCA): Thirteen Years of Hemispheric in the Crown” for Neotropical Migrants Bird Conservation Guy Foulks, Program Coordinator, Division of Bird Habitat Conservation, U.S. Fish and Bird Conservation in 8 Wildlife Service (USFWS) Costa Rica’s Agricultural Matrix In 2000, responding to alarming declines in many Neotropical migratory bird popu- Uruguayan Rice Fields 10 lations due to habitat loss and degradation, Congress passed the Neotropical Migra- as Wintering Habitat for tory Bird Conservation Act (NMBCA). The legislation created a unique funding Neotropical Shorebirds source to foster the cooperative conservation needed to sustain these species through all stages of their life cycles, which occur throughout the Western Hemi- Conserving Antigua’s 12 sphere. Since its first year of appropriations in 2002, the NMBCA has become in- Most Critical Bird strumental to migratory bird conservation Habitat in the Americas. Neotropical Migratory 14 Bird Conservation in the The mission of the North American Bird Heart of South America Conservation Initiative is to ensure that populations and habitats of North Ameri- Aros/Yaqui River Habi- 16 ca's birds are protected, restored, and en- tat Conservation hanced through coordinated efforts at in- ternational, national, regional, and local Strategic Conservation 18 levels, guided by sound science and effec- in the Appalachians of tive management. The NMBCA’s mission Southern Quebec is to achieve just this for over 380 Neo- tropical migratory bird species by provid- ...and more! Cerulean Warbler, a Neotropical migrant, is a ing conservation support within and be- USFWS Bird of Conservation Concern and listed as yond North America—to Latin America Vulnerable on the International Union for Conser- Coordination and editorial vation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. -

SGCN) - Amphibians

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: June 13, 2014 Priority 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) - Amphibians High Regional ConservationPriority USFWS Birds of ConservationUSFWS ConcernBirdsof ClimateChange Vulnerability Northeast Odonate Assessment NortheastOdonate RecentSignificant Decline AmericanFisheries Society North American WaterbirdNorthAmerican RediscoveryPotential ShorebirdNorthAtlantic UnderstudiedTaxa Risk Of ExtirpationRiskOf Regional Endemic ShorebirdNational Partners In Flight Partners In MESA Proposed MESA FederalStatus IUCN Red List IUCN NatureServe State Status State Criteria1 Criteria2 Criteria3 Criteria4 Criteria5 Criteria6 Criteria7 COSEWIC NEWDTC NEPARC RSGCN ASMFC CommonName ScientificName Anura ( frogs and toads ) Northern Leopard Lithobates pipiens X X X Frog Mink Frog Lithobates X septentrionalis Caudata ( salamanders ) Blue-spotted Ambystoma laterale X X X Salamander Northern Spring Gyrinophilus X X Salamander porphyriticus porphyriticus Risk of Extirpation: Critically Endangered [CR]; Endangered [E] or [EN]; Threatened [T]; Vulnerable [VU]; Candidate [C]; Proposed Endangered [PE]; Proposed Threatened [PT] Amphibians Group Page 1 of 1 DRAFT Priority 2 SGCN Report - Page 1 of 33 Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: June 13, 2014 Priority 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) - Aquatic And Terrestrial Snails High Regional ConservationPriority USFWS Birds of ConservationUSFWS ConcernBirdsof ClimateChange Vulnerability Northeast Odonate Assessment NortheastOdonate -

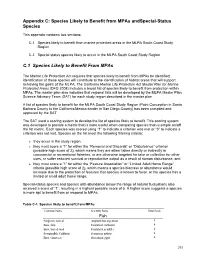

List of Species Likely to Benefit from Marine Protected Areas in The

Appendix C: Species Likely to Benefit from MPAs andSpecial-Status Species This appendix contains two sections: C.1 Species likely to benefit from marine protected areas in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.2 Special status species likely to occur in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.1 Species Likely to Benefit From MPAs The Marine Life Protection Act requires that species likely to benefit from MPAs be identified; identification of these species will contribute to the identification of habitat areas that will support achieving the goals of the MLPA. The California Marine Life Protection Act Master Plan for Marine Protected Areas (DFG 2008) includes a broad list of species likely to benefit from protection within MPAs. The master plan also indicates that regional lists will be developed by the MLPA Master Plan Science Advisory Team (SAT) for each study region described in the master plan. A list of species likely to benefit for the MLPA South Coast Study Region (Point Conception in Santa Barbara County to the California/Mexico border in San Diego County) has been compiled and approved by the SAT. The SAT used a scoring system to develop the list of species likely to benefit. This scoring system was developed to provide a metric that is more useful when comparing species than a simple on/off the list metric. Each species was scored using “1” to indicate a criterion was met or “0” to indicate a criterion was not met. Species on the list meet the following filtering criteria: they occur in the study region, they must score a “1” for either -

Checklist of Suffolk Birds

Suffolk Bird Checklist status up to and including 2001 records (2002 & 2003 where stated) - not including BOURC category E R = records considered by BBRC r = records considered by SORC, requiring full descriptions see end of list for Category D and abundance codes red-throated diver common winter visitor and passage migrant, rare inland black-throated diver uncommon winter visitor and passage migrant, rare inland great northern diver uncommon winter visitor and passage migrant yellow (white)-billed diver R accidental, 3 records; 1852, 1978 and 1994 little grebe locally common resident, passage migrant and winter visitor great crested grebe locally common resident, passage migrant and winter visitor red-necked grebe uncommon winter visitor and passage migrant, mostly coastal slavonian grebe uncommon winter visitor and passage migrant, mostly coastal black-necked grebe uncommon winter visitor and passage migrant northern fulmar fairly common summer visitor and passage migrant Cory's shearwater r very rare (autumn) passage migrant; 28 records of 37 individuals, all post 1973 great shearwater r accidental, 6 records; 3 post 1950 sooty shearwater uncommon autumn migrant Manx shearwater uncommon passage migrant, mainly autumn Balearic shearwater r very rare passage migrant, 9 records, all since 1998 Leach's storm petrel r scarce passage migrant European storm petrel r very rare passage migrant, 28 individuals since 1950 northern gannet common offshore passage migrant great cormorant locally common passage migrant and winter visitor, a few oversummer -

First Record of Long-Billed Curlew Numenius Americanus in Peru and Other Observations of Nearctic Waders at the Virilla Estuary Nathan R

Cotinga 26 First record of Long-billed Curlew Numenius americanus in Peru and other observations of Nearctic waders at the Virilla estuary Nathan R. Senner Received 6 February 2006; final revision accepted 21 March 2006 Cotinga 26(2006): 39–42 Hay poca información sobre las rutas de migración y el uso de los sitios de la costa peruana por chorlos nearcticos. En el fin de agosto 2004 yo reconocí el estuario de Virilla en el dpto. Piura en el noroeste de Peru para identificar los sitios de descanso para los Limosa haemastica en su ruta de migración al sur y aprender más sobre la migración de chorlos nearcticos en Peru. En Virilla yo observí más de 2.000 individuales de 23 especios de chorlos nearcticos y el primer registro de Numenius americanus de Peru, la concentración más grande de Limosa fedoa en Peru, y una concentración excepcional de Limosa haemastica. La combinación de esas observaciones y los resultados de un estudio anterior en el invierno boreal sugiere la posibilidad que Virilla sea muy importante para chorlos nearcticos en Peru. Las observaciones, también, demuestren la necesidad hacer más estudios en la costa peruana durante el año entero, no solemente durante el punto máximo de la migración de chorlos entre septiembre y noviembre. Shorebirds are poorly known in Peru away from bordered for a few hundred metres by sand and established study sites such as Paracas reserve, gravel before low bluffs rise c.30 m. Very little dpto. Ica, and those close to metropolitan areas vegetation grows here, although cows, goats and frequented by visiting birdwatchers and tour pigs owned by Parachique residents graze the area. -

Vertebrate Diversity Benefiting from Carrion Provided by Pumas And

Biological Conservation 215 (2017) 123–131 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Short communication Vertebrate diversity benefiting from carrion provided by pumas and other subordinate, apex felids MARK L. Mark Elbroch⁎, Connor O'Malley, Michelle Peziol, Howard B. Quigley Panthera, 8 West 40th Street, 18th Floor, New York, NY 10018, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Carrion promotes biodiversity and ecosystem stability, and large carnivores provide this resource throughout the Biodiversity year. In particular, apex felids subordinate to other carnivores contribute more carrion to ecological commu- Carnivores nities than other predators. We measured vertebrate scavenger diversity at puma (Puma concolor) kills in the Food webs Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, and utilized a model-comparison approach to determine what variables influ- Scavenging enced scavenger diversity (Shannon's H) at carcasses. We documented the highest vertebrate scavenger diversity of any study to date (39 birds and mammals). Scavengers represented 10.9% of local birds and 28.3% of local mammals, emphasizing the diversity of food-web vectors supported by pumas, and the positive contributions of pumas and potentially other subordinate, apex felids to ecological stability. Scavenger diversity at carcasses was most influenced by the length of time the carcass was sampled, and the biological variables, temperature and prey weight. Nevertheless, diversity was relatively consistent across carcasses. We also identified six additional stalk- and-ambush carnivores weighing > 20 kg, that feed on prey larger than themselves, and are subordinate to other predators. Together with pumas, these seven felids may provide distinctive ecological functions through their disproportionate production of carrion and subsequent contributions to biodiversity. -

British Birds |

VOL. LU JULY No. 7 1959 BRITISH BIRDS WADER MIGRATION IN NORTH AMERICA AND ITS RELATION TO TRANSATLANTIC CROSSINGS By I. C. T. NISBET IT IS NOW generally accepted that the American waders which occur each autumn in western Europe have crossed the Atlantic unaided, in many (if not most) cases without stopping on the way. Yet we are far from being able to answer all the questions which are posed by these remarkable long-distance flights. Why, for example, do some species cross the Atlantic much more frequently than others? Why are a few birds recorded each year, and not many more, or many less? What factors determine the dates on which they cross? Why are most of the occurrences in the autumn? Why, despite the great advantage given to them by the prevail ing winds, are American waders only a little more numerous in Europe than European waders in North America? To dismiss the birds as "accidental vagrants", or to relate their occurrence to weather patterns, as have been attempted in the past, may answer some of these questions, but render the others still more acute. One fruitful approach to these problems is to compare the frequency of the various species in Europe with their abundance, migratory behaviour and ecology in North America. If the likelihood of occurrence in Europe should prove to be correlated with some particular type of migration pattern in North America this would offer an important clue as to the causes of trans atlantic vagrancy. In this paper some aspects of wader migration in North America will be discussed from this viewpoint. -

Migratory Shorebird Guild

Migratory Shorebird Guild Piping Plover Charadrius melodus Sanderling Calidris alba Semipalmated Plover Charadrius semipalmatus Red Knot Calidris canutus Black-bellied Plover Pluvialis squatarola Marbled Godwit Limosa fedoa American Golden Plover Pluvialis dominica Buff-breasted Sandpiper Tryngites subruficollis Wimbrel Numenius phaeopus White-rumped Sandpiper Calidris fuscicollis Long-billed Curlew Numenius americanus Pectoral Sandpiper Calidris melanotos Greater Yellowlegs Tringa melanoleuca Purple Sandpiper Calidris maritima Lesser Yellowlegs Tringa flavipes Stilt Sandpiper Calidris himantopus Solitary Sandpiper Tringa solitaria Wilson’s Snipe Gallinago gallinago delicata Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularia American Avocet Recurvirostra Americana Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda Least Sandpiper Calidris minutilla Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla Short-billed Dowitcher Limnodromus griseus Western Sandpiper Calidris mauri Long-billed Dowitcher Limnodromus scolopaceus Dunlin Calidris alpina Contributors: Felicia Sanders and Thomas M. Murphy DESCRIPTION Photograph by SC DNR Taxonomy and Basic Description The migratory shorebird guild is composed of birds in the Charadrii suborder. Migrants in South Carolina represent three families: Scolopacidae (sandpipers), Charadriidae (plovers) and Recurvirostridae (avocets). Sandpipers are the most diverse family of shorebirds. Their tactile foraging strategy encompasses probing in soft mud or sand for invertebrates. Plovers are medium size birds, with relatively short, thick bills and employ a distinctive foraging strategy. They stand, looking for prey and then run to feed on detected invertebrates. Avocets are large shorebirds with long recurved bills and partial webbing between the toes. They feed employing both tactile and visual methods. Shorebirds are characterized by long legs for wading and wings designed for quick flight and transcontinental migrations. Migrations can span continents; for example, red knots migrate from the Canadian arctic to the southern tip of South America. -

Notes on the Natural History of Juneau, Alaska

Notes on the Natural History of Juneau, Alaska Observations of an Eclectic Naturalist Volume 2 Animals L. Scott Ranger Working version of Jul. 8, 2020 A Natural History of Juneau, working version of Jul. 8, 2020 Juneau Digital Shaded-Relief Image of Alaska-USGS I-2585, In the Public Domain Natural History of Juneau, working version of Jul. 8, 2020 B Notes on the Natural History of Juneau, Alaska Observations of an Eclectic Naturalist Volume 2: Animals L. Scott Ranger www.scottranger.com, [email protected] Production Notes This is very much a work under construction. My notes are composed in Adobe InDesign which allows incredible precision of all the elements of page layout. My choice of typefaces is very specific. Each must include a complete set of glyphs and extended characters. For my etymologies the font must include an easily recognized Greek and the occasional Cyrillic and Hebrew. All must be legible and easily read at 10 points. Adobe Garamond Premier Pro is my specifically chosen text typeface. I find this Robert Slimbach 1989 revision of a typeface created by Claude Garamond (c. 1480–1561) to be at once fresh and classic. Long recognized as one of the more legible typefaces, I find it very easy on the eye at the 10 point size used here. I simply adore the open bowls of the lower case letters and find the very small counters of my preferred two- storied “a” and the “e” against its very open bowl elegant. Garamond’s ascenders and decenders are especially long and help define the lower case letters with instant recognition. -

54971 GPNC Shorebirds

A P ocket Guide to Great Plains Shorebirds Third Edition I I I By Suzanne Fellows & Bob Gress Funded by Westar Energy Green Team, The Nature Conservancy, and the Chickadee Checkoff Published by the Friends of the Great Plains Nature Center Table of Contents • Introduction • 2 • Identification Tips • 4 Plovers I Black-bellied Plover • 6 I American Golden-Plover • 8 I Snowy Plover • 10 I Semipalmated Plover • 12 I Piping Plover • 14 ©Bob Gress I Killdeer • 16 I Mountain Plover • 18 Stilts & Avocets I Black-necked Stilt • 19 I American Avocet • 20 Hudsonian Godwit Sandpipers I Spotted Sandpiper • 22 ©Bob Gress I Solitary Sandpiper • 24 I Greater Yellowlegs • 26 I Willet • 28 I Lesser Yellowlegs • 30 I Upland Sandpiper • 32 Black-necked Stilt I Whimbrel • 33 Cover Photo: I Long-billed Curlew • 34 Wilson‘s Phalarope I Hudsonian Godwit • 36 ©Bob Gress I Marbled Godwit • 38 I Ruddy Turnstone • 40 I Red Knot • 42 I Sanderling • 44 I Semipalmated Sandpiper • 46 I Western Sandpiper • 47 I Least Sandpiper • 48 I White-rumped Sandpiper • 49 I Baird’s Sandpiper • 50 ©Bob Gress I Pectoral Sandpiper • 51 I Dunlin • 52 I Stilt Sandpiper • 54 I Buff-breasted Sandpiper • 56 I Short-billed Dowitcher • 57 Western Sandpiper I Long-billed Dowitcher • 58 I Wilson’s Snipe • 60 I American Woodcock • 61 I Wilson’s Phalarope • 62 I Red-necked Phalarope • 64 I Red Phalarope • 65 • Rare Great Plains Shorebirds • 66 • Acknowledgements • 67 • Pocket Guides • 68 Supercilium Median crown Stripe eye Ring Nape Lores upper Mandible Postocular Stripe ear coverts Hind Neck Lower Mandible ©Dan Kilby 1 Introduction Shorebirds, such as plovers and sandpipers, are a captivating group of birds primarily adapted to live in open areas such as shorelines, wetlands and grasslands.