PDF (Published Version)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Written Submission from the Lac La Ronge Indian Band Mémoire De

CMD 21-H2.12 File / dossier : 6.01.07 Date: 2021-03-17 Edocs: 6515664 Written submission from the Mémoire de Lac La Ronge Indian Band Lac La Ronge Indian Band In the Matter of the À l’égard de Cameco Corporation, Cameco Corporation, Cigar Lake Operation établissement de Cigar Lake Application for the renewal of Cameco’s Demande de renouvellement du permis de mine uranium mine licence for the Cigar Lake d’uranium de Cameco pour l’établissement de Operation Cigar Lake Commission Public Hearing Audience publique de la Commission April 28-29, 2021 28 et 29 avril 2021 This page was intentionally Cette page a été intentionnellement left blank laissée en blanc ADMINISTRATION BOX 480, LA RONGE SASK. S0J 1L0 Lac La Ronge PHONE: (306) 425-2183 FAX: (306) 425-5559 1-800-567-7736 Indian Band March 16, 2021 Senior Tribunal Officer, Secretariat Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission 280 Slater St. Ottawa ON Email: [email protected] Re: Intervention letter on renewal application for Cameco’s uranium mine license for the Cigar Lake Operation Thank you for the opportunity to submit this intervention letter on behalf of the Lac La Ronge Indian Band (LLRIB). The LLRIB is the largest First Nation in Saskatchewan, and one of the largest in Canada with over 11,408 band members. The LLRIB lands, 19 reserves in total, extend from farmlands in central Saskatchewan all the way north through the boreal forest to the Churchill River and beyond. We are a Woodland Cree First Nation, members of the Prince Albert Grand Council and we pride ourselves on a commitment to education opportunities, business successes, and improving the well-being of our band members. -

La Ronge Integrated Land Use Management Plan Background

La Ronge Integrated Land Use Management Plan Background Document La Ronge Integrated Land Use Management Plan, January 2003 La Ronge Integrated Land Use Management Plan Management Plan La Ronge Integrated Land Use Management Plan, January 2003 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE# Lists of Tables and Figures................................................................................... ii Chapter 1 - The La Ronge Planning Area........................................................... 1 Chapter 2 - Ecological and Natural Resource Description............................... 4 2.1 Landscape Area Description..................................................... 4 2.1.1 Sisipuk Plain Landscape Area................................... 4 2.1.2 La Ronge Lowland Landscape Area.......................... 4 2.2 Forest Resources..................................................................... 4 2.3 Water Resources..................................................................... 5 2.4 Geology.................................................................................... 5 2.5 Wildlife Resources.................................................................... 6 2.6 Fish Resources......................................................................... 9 Chapter 3 - Existing Resource Uses and Values................................................11 3.1 Timber......................................................................................12 3.2 Non-Timber Forest Products......................................................13 -

2021 Saskatchewan Provincial Parks Guide

Saskatchewan SERVICES AT A GLANCE Boat Launch Boat Camping Seasonal Camping Camp-Easy Fishing Golfing Washrooms Showers Area Picnic Trails Online Reservations Provincial Parks NORTHERN Athabasca Sand Dunes * Bronson Forest * * * * * * * Guide Candle Lake * * * * * * * * * * Clarence-Steepbank Lakes * Clearwater River * * * * Cumberland House Fort Pitt * * * Great Blue Heron * * * * * * * * * * Lac La Ronge * * * * * * * * * Athabasca Makwa Lake * * * * * * * * * * Sand Dunes Meadow Lake * * * * * * * * * * Northern Narrow Hills * * * * * * * * * * Clearwater Steele Narrows * * * River Wildcat Hill * CENTRAL The Battlefords * * * * * * * * * * Blackstrap * * * * * * * * * Duck Mountain * * * * * * * * * * * Fort Carlton * * * * * La Ronge Good Spirit Lake * * * * * * * * * * * Lac La Ronge Meadow Greenwater Lake Lake * * * * * * * * * Clarence- Steepbank Pike Lake Lakes * * * * * * * * * * Cumberland Steele Narrows Narrow Porcupine Hills Hills House * * * * * Bronson Makwa Forest Lake SOUTHERN Great Blue Candle Lake Fort Pitt GreatHeron Blue Candle Lake Buffalo Pound * * * * * * * * * * Fort Pitt Heron The Cannington Manor Lloydminster Wildcat Hill * * Battlefords Prince Albert Melfort Fort Carlton Crooked Lake North * * * * * * * * * * * Battleford Greenwater Lake Cypress Hills * * * * * * * * * * Humboldt Central Duck Danielson * * * * * * * * * Saskatoon Mountain Pike Lake Good Pike Lake Spirit Douglas Blackstrap Touchwood SLakpirite * * * * * * * * * * Blackstrap HillsTouchwood Post Lake Hills Post Echo Valley Kindersley * * * * * -

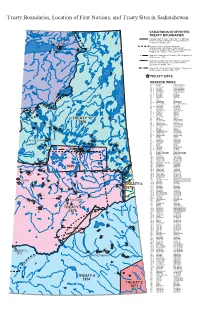

Treaty Boundaries Map for Saskatchewan

Treaty Boundaries, Location of First Nations, and Treaty Sites in Saskatchewan VARIATIONS IN DEPICTED TREATY BOUNDARIES Canada Indian Treaties. Wall map. The National Atlas of Canada, 5th Edition. Energy, Mines and 229 Fond du Lac Resources Canada, 1991. 227 General Location of Indian Reserves, 225 226 Saskatchewan. Wall Map. Prepared for the 233 228 Department of Indian and Northern Affairs by Prairie 231 224 Mapping Ltd., Regina. 1978, updated 1981. 232 Map of the Dominion of Canada, 1908. Department of the Interior, 1908. Map Shewing Mounted Police Stations...during the Year 1888 also Boundaries of Indian Treaties... Dominion of Canada, 1888. Map of Part of the North West Territory. Department of the Interior, 31st December, 1877. 220 TREATY SITES RESERVE INDEX NO. NAME FIRST NATION 20 Cumberland Cumberland House 20 A Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 B Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 C Muskeg River Cumberland House 20 D Budd's Point Cumberland House 192G 27 A Carrot River The Pas 28 A Shoal Lake Shoal Lake 29 Red Earth Red Earth 29 A Carrot River Red Earth 64 Cote Cote 65 The Key Key 66 Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 66 A Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 68 Pheasant Rump Pheasant Rump Nakota 69 Ocean Man Ocean Man 69 A-I Ocean Man Ocean Man 70 White Bear White Bear 71 Ochapowace Ochapowace 222 72 Kahkewistahaw Kahkewistahaw 73 Cowessess Cowessess 74 B Little Bone Sakimay 74 Sakimay Sakimay 74 A Shesheep Sakimay 221 193B 74 C Minoahchak Sakimay 200 75 Piapot Piapot TREATY 10 76 Assiniboine Carry the Kettle 78 Standing Buffalo Standing Buffalo 79 Pasqua -

2017 Anglers Guide.Cdr

Saskatchewan Anglers’ Guide 2017 saskatchewan.ca/fishing Free Fishing Weekends July 8 and 9, 2017 February 17, 18 and 19, 2018 Minister’s Message I would like to welcome you to a new season of sport fishing in Saskatchewan. Saskatchewan's fishery is a priceless legacy, and it is the ministry's goal to maintain it in a healthy, sustainable state to provide diverse benefits for the province. As part of this commitment, a portion of all angling licence fees are dedicated to enhancing fishing opportunities through the Fish and Wildlife Development Fund (FWDF). One of the activities the FWDF supports is the operation of Scott Moe the Saskatchewan Fish Culture Station, which plays a Minister of Environment key role in managing a number of Saskatchewan's sport fisheries. To meet the province's current and future stocking needs, a review of the station's aging infrastructure was recently completed, with a multi-year plan for modernization and refurbishment to begin in 2017. In response to the ongoing threat of aquatic invasive species, the ministry has increased its prevention efforts on several fronts, including increasing public awareness, conducting watercraft inspections and monitoring high- risk waters. I ask everyone to continue their vigilance against the threat of aquatic invasive species by ensuring that your watercraft and related equipment are cleaned, drained and dried prior to moving from one body of water to another. Responsible fishing today ensures fishing opportunities for tomorrow. I encourage all anglers to do their part by becoming familiar with this guide and the rules and regulations that pertain to your planned fishing activity. -

TREATY No. 10 REPORTS of COMMISSIONERS

TREATY No. 10 AND REPORTS OF COMMISSIONERS LAYOUT IS NOT EXACTLY LIKE ORIGINAL TRANSCRIBED FROM: Reprinted from the edition of 1907 by © ROGER DUHAMEL, F.R.S.C. QUEEN'S PRINTER AND CONTROLLER OF STATIONERY OTTAWA, 1966 Cat. No.: Ci 72-1066 IAND Publication No. QS-2048-000-EE-A-11 ORDER IN COUNCIL SETTING UP COMMISSION FOR TREATY No. 10 P.C. No. 1459 On a Report dated 12th July 1906, from the Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, stating that the aboriginal title has not been extinguished in the greater portion of that part of the Province of Saskatchewan which lies north of the 54th parallel of latitude and in a small adjoining area in Alberta; that the Indians and Half-breeds of that territory are similarly situated to those whose country lies immediately to the south and west, whose claims have already been extinguished by, in the case of those who are Indians, a payment of a gratuity and annuity and the setting aside of lands as reserves, and in the case of those who are Half-breeds, by the issue of scrip; and they have from time to time pressed their claims for settlement on similar lines; that it is in the public interest that the whole of the territory included within the boundaries of the Provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta should be relieved of the claims of the aborigines; and that $12,000.00 has been included in the estimates for expenses in the making of a treaty with Indians and in settling the claims of the Half-breeds and for paying the usual gratuities to the Indians. -

Saskatchewan 2011 | 2012 PROVINCIAL PARKS GUIDE

parks Saskatchewan 2011 | 2012 PROVINCIAL PARKS GUIDE Saskatchewan Ministry of Tourism, Parks, Culture and Sport saskparks.net 1 Lac La Ronge Provincial Park (Nistowiak Falls) Lac La Ronge Provincial Now, our 34 provincial parks, This is an exciting time for our eight historic sites, 130 recreation provincial parks. We are working sites and 24 protected areas have to ensure future generations will a total land area of 1.4 million be able to continue to explore, hectares and contain some of relax and enjoy the many in Saskatchewan’s the province’s most unique, outdoor recreation opportunities provincial parks! biologically-diverse and beautiful and natural and cultural areas natural and cultural landscapes. in our provincial parks. This year, the provincial This summer, be sure to take in Enjoy your visit to Saskatchewan’s park system turns 80 – a birthday celebrations at a park provincial parks! milestone that will be of your choice. You can find greeted by celebrations out what is being planned by right across the system. contacting the park or by visiting our website at www.saskparks.net. Saskatchewan’s first six provincial parks We are also continuing to improve Bill Hutchinson were established in our provincial parks by adding Minister of Tourism, Parks, 1931 – a year after the electrical service to campsites, Culture and Sport federal government transferred renewing or replacing service control of natural resources centres and replacing boat docks, to the province. One of those picnic tables and barbecues. original parks, Little Manitou, is currently a regional park. Cover image: Lake Diefenbaker (near Elbow Harbour Recreation Site) Contributing photography: Tourism Saskatchewan, Paul Austring Photography, Davin Andrie, Greg Huszar Photography, Saskatchewan Archives Board 4 Park Locator Map 6 Start Packing 8 Your Spot Awaits 10 Don't Forget 12 Celebrating our 80th Anniversary 14 Through The Years 16 Endless Possibilities 18 Southwest Cypress Hills, St. -

WALLEYE Stizostedion V

FIR/S119 FAO Fisheries Synopsis No. 119 Stizostedion v. vitreum 1,70(14)015,01 SYNOPSIS OF BIOLOGICAL DATA ON THE WALLEYE Stizostedion v. vitreum (Mitchill 1818) A, F - O FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OFTHE UNID NP.TION3 FISHERIES SYNOR.9ES This series of documents, issued by FAO, CSI RO, I NP and NMFS, contains comprehensive reviews of present knowledge on species and stocks of aquatic organisms of present or potential economic interest. The Fishery Resources and Environment Division of FAO is responsible for the overall coordination of the series. The primary purpose of this series is to make existing information readily available to fishery scientists according to a standard pattern, and by so doing also to draw attention to gaps in knowledge. It is hoped 41E11 synopses in this series will be useful to other scientists initiating investigations of the species concerned or or rMaIeci onPs, as a means of exchange of knowledge among those already working on the species, and as the basis íoi study of fisheries resources. They will be brought up to date from time to time as further inform.'t:i available. The documents of this Series are issued under the following titles: Symbol FAO Fisheries Synopsis No. 9R/S CS1RO Fisheries Synopsis No. INP Sinopsis sobre la Pesca No. NMFS Fisheries Synopsis No. filMFR/S Synopses in these series are compiled according to a standard outline described in Fib/S1 Rev. 1 (1965). FAO, CSI RO, INP and NMFS are working to secure the cooperation of other organizations and of individual scientists in drafting synopses on species about which they have knowledge, and welcome offers of help in this task. -

Saskatchewan's Northern Wilderness and Southern Ranch Hospitality

SASKATCHEWAN‘S NORTHERN WILDERNESS AND SOUTHERN RANCH HOSPITALITY Travel time: 14 days from/to Edmonton Distance: approximately 2,300 km Saskatchewan is big – a sweeping 652,000 sq. km, in fact. Breathtaking landscapes feature throughout the province. In southern Saskatchewan, vast tracts of prairie grassland beneath endless blue create the perfect backdrop for a western-style ranch vacation. In northern Saskatchewan, the picture is completely different. Pristine lakes (numbering almost 100,000) are framed by lush boreal forest. Exciting outdoor adventures and warm hospitality make every visit to Saskatchewan a remarkable experience. Day 1: Arrive in Edmonton, Alberta Welcome to Edmonton, Alberta’s capital city. Pick up your rental car and explore Edmonton‘s downtown. End the day with a pleasant walk along the shore of the North Saskatchewan River. Day 2: Drive to Meadow Lake Provincial Park (410 km) Leaving Edmonton, head east on the Trans-Canada Yellowhead Highway (No.16). About 45 km from the city, you will reach Elk Island National Park. It is situated in a wooded stretch of the Beaver Hills, a natural hillside landscape with numerous lakes, swamps and ponds. The park offers some of the best wildlife viewing in North America, including herds of Plains and Wood bison. Continuing east, you will soon cross the border into Saskatchewan. Your destination for today is Meadow Lake Provincial Park. Day 3: Meadow Lake Provincial Park Covering 1,600 sq. km, Meadow Lake Provincial Park features more than 20 lakes, rivers and streams. Consider a canoe adventure on the Waterhen River, which winds its way through the park and connects the string of lakes. -

Table of Contents

LAC LA RONGE INDIAN BAND EDUCATION, TRAINING & EMPLOYMENT BRANCH Information Handbook 2012-2013 “Demonstrating the Virtues of Life Through Modelling and Living to Build Character” TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 1 BAND DIRECTORY 2 Chief and Council 3 Administration/Project Venture/Court Workers 4 Social Development/Group Home/ JRMCC Hall & Arena 5 Public Works/Facilities 6 Health Services 7 Indian Child and Family Services 9 EDUCATION DIRECTORY 10 Education Administration Organizational Chart 11 Post Secondary Board/Daycare Board 12 Local School Boards (Sucker River, La Ronge and Hall Lake) 13 Education Central Office 14 Daycare 15 Woodland Cree Staff List 16 LLRIB School Principals and Address List 17 School Staff 18 VISION, MISSION, GOALS, OBJECTIVES Vision, Mission Statement 24 Definitions 25 Daycare Objectives 26 Goals 27 Objectives 28 ROLES School Board 29 Principal 30 Teachers 33 Elder 35 Guidance Counselor/Home School Coordinator 36 Students 37 THE COMMUNICATION PROCESS 38 STUDENT SERVICES/YOUTH HAVEN 41 THE COMMUNITIES 43 2012-2013 SCHOOL YEAR 46 2012-2013 SCHOOL BOARD SCHEDULE/CONTACT NUMBERS 49 VIRTUES 50 CIRCLE OF COURAGE 51 SRO CREE SYLLABIC CHART 52 FOOD GUIDE 53 PREFACE This is the twenty-eighth edition of the Lac La Ronge Indian Band Education Branch Handbook. The Vision, Mission, Goals and Objectives have been reviewed and revised by the administrators group, which are the school principals, the consultants in Central Office and the Director of Education. This handbook is intended to provide general information to the education staff, particularly new staff, the school board members, council members and visitors to the Band. The theme for this year, “Demonstrating the Virtues of Life Through Modelling and Living to Build Character” reflects the objective by working together and being creative, we can achieve excellence in the education program. -

Northern Saskatchewan Arts and Culture Handbook

Northern Saskatchewan Arts and Culture Handbook Compiled and edited by Miriam Körner for the Northern Sport, Culture and Recreation District Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank the Northern Sport, Culture and Recreation District for contracting me to develop the Northern Saskatchewan Arts and Culture Handbook. Through this work I had the rare opportunity to visit many of Northern Saskatchewan’s finest arts and crafts people. I would like to thank all the artists that invited me into their homes, and shared their stories TheThe Northern Sport, Culture & with me. It was a wonderful experience and there is just one regret: That I did not have more RecreationRecreation DistrictDistrict wwouldould liklikee to time to spend with all of you! thankthank theirtheir sponsors:sponsors: This project would not have been possible without the outstanding support through dedicated individuals that helped me along my journey through northern communities. I especially would like to thank Rose Campbell & the Ospwakun Sepe School in Brabant; Simon Bird and Mary Thomas & the Reindeer Lake School in Southend; Marlene Naldzil & the Fond du Lac Denesuline First Nation Band Office, Rita Adam & the Father Gamache Memorial School, Flora Augier for room and board; Raymond McDonald and Corinne Sayazie & the Black Lake Denesuline Nation Band Office with special thanks to Mary Jane Cook for a great job finding artists, translating and lots of fun! Thanks to the Peter Ballantyne Cree Nation Band Office in Pelican Narrows and special thanks to Georgina Linklater for driving as well as Sheldon Dorion and Gertie Dorion for translating. Too bad I couldn’t stay longer! In Sandy Bay I would like to thank Lorraine Bear & the Hector Thiboutot Community School. -

Milebymile.Com Personal Road Trip Guide Saskatchewan Highway #102 "Highway 102 La Ronge to Missinipe (Otter Rapids at Churchill River Crossing)"

MileByMile.com Personal Road Trip Guide Saskatchewan Highway #102 "Highway 102 La Ronge to Missinipe (Otter Rapids at Churchill River Crossing)" Kms ITEM SUMMARY 0.0 Town of La Ronge, SK. Town of La Ronge, Sk. All services Lac La Ronge Provincial Park is Hospital Turnoff Road. situated in the heart of the Churchill River system, where voyageurs once transported furs to Hudson's Bay. Access to Lac La Ronge Provincial Park campgrounds. NOTE: For highway travel via Saskatchewan Highway #2 South : - See Road Map Highway Travel Guide Prince Albert, SK. to Lac la Ronge, SK for driving directions. 0.5 La Ronge Industrial Park Highway turnoff to La Ronge Industrial Park, Lakeland College, Boardman Street. 1.0 Information Map Highway pullout and Information and Direction Map 2.7 Highway Turnoff Access to LaRonge House Boat Charters, Eagle Point Resort, golfing 9 holes 4.2 La Ronge, SK, Airport Highway Turnoff to La Ronge Airport 4.7 Forest Fire Management Forest Fire Management Branch Air Tanker Base 16.0 Highway Turnoff Access to English bay, SK. B & L Cabins, Four Seasons Resort 4 km's 16.8 Highway Turnoff Access to Nemeiben Lake, Saskatchewan, 7 km's, to Lindwood Lodge. 20.7 Waden Bay Correctional Highway Access to Correctional Center Center 24.1 Waden Bay Highway Turnoff to Waden Bay Resort, camping,showers, fishing,store. Wadin Bay Campground is designed in a series of loops. Two sandy beaches and features a good playground and culvert style barbecue pits Limited wheelchair access, boat launch, fishing, cross-country skiing, major credit cards, telephone and showers.