Your Chess Brain Cyrus Lakdawala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taming Wild Chess Openings

Taming Wild Chess Openings How to deal with the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly over the chess board By International Master John Watson & FIDE Master Eric Schiller New In Chess 2015 1 Contents Explanation of Symbols ���������������������������������������������������������������� 8 Icons ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Introduction �������������������������������������������������������������������������� 10 BAD WHITE OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 18 Halloween Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♘c3 ♘f6 4.♘xe5 ♘xe5 5.d4 . 18 Grünfeld Defense: The Gibbon: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 g6 3.♘c3 d5 4.g4 . 20 Grob Attack: 1.g4 . 21 English Wing Gambit: 1.c4 c5 2.b4 . 25 French Defense: Orthoschnapp Gambit: 1.e4 e6 2.c4 d5 3.cxd5 exd5 4.♕b3 . 27 Benko Gambit: The Mutkin: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 c5 3.d5 b5 4.g4 . 28 Zilbermints - Benoni Gambit: 1.d4 c5 2.b4 . 29 Boden-Kieseritzky Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗c4 ♘f6 4.♘c3 ♘xe4 5.0-0 . 31 Drunken Hippo Formation: 1.a3 e5 2.b3 d5 3.c3 c5 4.d3 ♘c6 5.e3 ♘e7 6.f3 g6 7.g3 . 33 Kadas Opening: 1.h4 . 35 Cochrane Gambit 1: 5.♗c4 and 5.♘c3 . 37 Cochrane Gambit 2: 5.d4 Main Line: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘f6 3.♘xe5 d6 4.♘xf7 ♔xf7 5.d4 . 40 Nimzowitsch Defense: Wheeler Gambit: 1.e4 ♘c6 2.b4 . 43 BAD BLACK OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 44 Khan Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♗c4 d5 . 44 King’s Gambit: Nordwalde Variation: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♕f6 . 45 King’s Gambit: Sénéchaud Countergambit: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♗c5 3.♘f3 g5 . -

Preparation of Papers for R-ICT 2007

Chess Puzzle Mate in N-Moves Solver with Branch and Bound Algorithm Ryan Ignatius Hadiwijaya / 13511070 Program Studi Teknik Informatika Sekolah Teknik Elektro dan Informatika Institut Teknologi Bandung, Jl. Ganesha 10 Bandung 40132, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract—Chess is popular game played by many people 1. Any player checkmate the opponent. If this occur, in the world. Aside from the normal chess game, there is a then that player will win and the opponent will special board configuration that made chess puzzle. Chess lose. puzzle has special objective, and one of that objective is to 2. Any player resign / give up. If this occur, then that checkmate the opponent within specifically number of moves. To solve that kind of chess puzzle, branch and bound player is lose. algorithm can be used for choosing moves to checkmate the 3. Draw. Draw occur on any of the following case : opponent. With good heuristics, the algorithm will solve a. Stalemate. Stalemate occur when player doesn‟t chess puzzle effectively and efficiently. have any legal moves in his/her turn and his/her king isn‟t in checked. Index Terms—branch and bound, chess, problem solving, b. Both players agree to draw. puzzle. c. There are not enough pieces on the board to force a checkmate. d. Exact same position is repeated 3 times I. INTRODUCTION e. Fifty consecutive moves with neither player has Chess is a board game played between two players on moved a pawn or captured a piece. opposite sides of board containing 64 squares of alternating colors. -

The London System Is a Chess Opening That Usually Arises After 1.D4 and 2.Bf4, Or 2.Nf3 and 3.Bf4

ICC presents: The London System by GM Damian Lemos This is a guide that comes with the video course “The London System”. We highly recommend you first watch the video series before completing these exercises. To watch the videos, click here. The London System is a chess opening that usually arises after 1.d4 and 2.Bf4, or 2.Nf3 and 3.Bf4. It is a "system" opening that can be used against virtually any black defense and thus comprises a smaller body of opening theory than many other openings. The London is a set of solid lines where after 1.d4 White quickly develops his dark- squared bishop to f4 and normally bolsters his center with pawns on c3 and e3 rather than expanding. Although it has the potential for a quick kingside attack, the white forces are generally flexible enough to engage in a battle anywhere on the board. Historically it developed into a system mainly from three variations: 1.d4 d5 2.Nf3 Nf6 3.Bf4 1.d4 Nf6 2.Nf3 e6 3.Bf4 1.d4 Nf6 2.Nf3 g6 3.Bf4 "There is one opening that shines above all others when comparing reward payout to the input effort," says Zhigen Lin. "It is relatively quick to learn and obscure enough that even titled opponents may not have a proper antidote lined up." He is - of course - talking about the London System, popularized by the London BCF Congress Tournament of 1922. ICC presents: The London System by GM Damian Lemos Learning the London system is not hard, and it can be an essential arrow in your quiver! All you need is a set of videos by an experienced GM and, of course, a lot of practice! Damian Lemos became a chess Grandmaster at 18 and won the Gold Medal at the Pan-American Games U-20 in Colombia. -

TCEC15: the 15Th Top Chess Engine Championship

TCEC15: the 15th Top Chess Engine Championship Guy Haworth1 and Nelson Hernandez Reading, UK and Maryland, USA TCEC Season 15 started on March 5th 2019 with a more liberal Division 4 featuring several engines in their first TCEC season. At the top end, interest would centre on whether the recent entries, ETHEREAL, KOMODO MCTS and LEELA CHESS ZERO would again improve their already impressive performances. Fig. 1 and Table 1 provide the logos and details on the enlarged field of 44 engines. DP D1 D2 D3 D4 Fig. 1. Logos for the TCEC 15 engines (CPW, 2019) as in their original divisions. There were a few nudges to the rules. In the event of network breaks, if both engines were in the 7-man and/or TCEC win (or draw) zone, the game was adjudicated as a win (or draw). Otherwise, TCEC resumed games with extra initialisation time rather than restart them. The common platform for TCEC15, as for TCEC14, consisted of two computers. One was the estab- lished, formidable 44-core server of TCEC11-14 (Intel, 2017) with 64GiB of DDR4 ECC RAM and a Crucial CT250M500 240 GB SSD for the EGTs. The ‘GPU server’, upgraded to a Quad Core i5 3570k with 32GiB DDR3 RAM, sported Nvidia (2018) GeForce RTX 2080 Ti and 2080 GPUs. 1 Corresponding author: [email protected] Table 1. The TCEC15 engines (CPW, 2019), details, authors and progress. Engine Initial proto- Hash Countr Final # thr. EGTs Authors ab Name Version ELO Div. col Kb y Codes Div. 01 AS AllieStein v0.1-n4 2557 4b 3 uci 7,168 — Adam Treat and Mark Jordan US ↗↗ ↗↗P 02 An Andscacs 0.95123 3469 1 43 uci 8,192 — Daniel José Queraltó AD →1 03 Ar Arasan TCEC15 3290 3 43 uci 16,384 Syz. -

Chess Openings

Chess Openings PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 10 Jun 2014 09:50:30 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Chess opening 1 e4 Openings 25 King's Pawn Game 25 Open Game 29 Semi-Open Game 32 e4 Openings – King's Knight Openings 36 King's Knight Opening 36 Ruy Lopez 38 Ruy Lopez, Exchange Variation 57 Italian Game 60 Hungarian Defense 63 Two Knights Defense 65 Fried Liver Attack 71 Giuoco Piano 73 Evans Gambit 78 Italian Gambit 82 Irish Gambit 83 Jerome Gambit 85 Blackburne Shilling Gambit 88 Scotch Game 90 Ponziani Opening 96 Inverted Hungarian Opening 102 Konstantinopolsky Opening 104 Three Knights Opening 105 Four Knights Game 107 Halloween Gambit 111 Philidor Defence 115 Elephant Gambit 119 Damiano Defence 122 Greco Defence 125 Gunderam Defense 127 Latvian Gambit 129 Rousseau Gambit 133 Petrov's Defence 136 e4 Openings – Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence, Alapin Variation 159 Sicilian Defence, Dragon Variation 163 Sicilian Defence, Accelerated Dragon 169 Sicilian, Dragon, Yugoslav attack, 9.Bc4 172 Sicilian Defence, Najdorf Variation 175 Sicilian Defence, Scheveningen Variation 181 Chekhover Sicilian 185 Wing Gambit 187 Smith-Morra Gambit 189 e4 Openings – Other variations 192 Bishop's Opening 192 Portuguese Opening 198 King's Gambit 200 Fischer Defense 206 Falkbeer Countergambit 208 Rice Gambit 210 Center Game 212 Danish Gambit 214 Lopez Opening 218 Napoleon Opening 219 Parham Attack 221 Vienna Game 224 Frankenstein-Dracula Variation 228 Alapin's Opening 231 French Defence 232 Caro-Kann Defence 245 Pirc Defence 256 Pirc Defence, Austrian Attack 261 Balogh Defense 263 Scandinavian Defense 265 Nimzowitsch Defence 269 Alekhine's Defence 271 Modern Defense 279 Monkey's Bum 282 Owen's Defence 285 St. -

Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA

First Steps : Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA www.everymanchess.com About the Author Cyrus Lakdawala is an International Master, a former National Open and American Open Cham- pion, and a six-time State Champion. He has been teaching chess for over 30 years, and coaches some of the top junior players in the U.S. Also by the Author: Play the London System A Ferocious Opening Repertoire The Slav: Move by Move 1...d6: Move by Move The Caro-Kann: Move by Move The Four Knights: Move by Move Capablanca: Move by Move The Modern Defence: Move by Move Kramnik: Move by Move The Colle: Move by Move The Scandinavian: Move by Move Botvinnik: Move by Move The Nimzo-Larsen Attack: Move by Move Korchnoi: Move by Move The Alekhine Defence: Move by Move The Trompowsky Attack: Move by Move Carlsen: Move by Move The Classical French: Move by Move Larsen: Move by Move 1...b6: Move by Move Bird’s Opening: Move by Move Petroff Defence: Move by Move Fischer: Move by Move Anti-Sicilians: Move by Move Opening Repertoire ... c6 First Steps: the Modern 3 Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Introduction 7 1 Essential Knowledge 9 2 Pawn Endings 23 3 Rook Endings 63 4 Queen Endings 119 5 Bishop Endings 144 6 Knight Endings 172 7 Minor Piece Endings 184 8 Rooks and Minor Pieces 206 9 Queen and Other Pieces 243 4 Introduction Why Study Chess at its Cellular Level? A chess battle is no less intense for its lack of brevity. Because my messianic mission in life is to make the chess board a safer place for students and readers, I break the seal of confessional and tell you that some students consider the idea of enjoyable endgame study an oxymoron. -

Deconstructing the Myth of Brilliant Attacking Play NEW!

U.S. TEAM TAKES GOLD AT THE WORLD SENIOR October 2018 | USChess.org Deconstructing the Myth of Brilliant Attacking Play NEW! GM Alexander Kalinin traces Fabiano Caruana’s career, analyses the role of his various trainers, explains the development of his playing style and points out what you can learn from his best games. With #!"$ paperback | 208 pages | $19.95 | from the publishers of A Magazine Free Ground Shipping On All Books, Software and DVDs at US Chess Sales $25.00 Minimum - Excludes Clearance, Shopworn and Items Otherwise Marked ADULT $ SCHOLASTIC $ 1 YEAR 49 1 YEAR 25 PREMIUM MEMBERSHIP PREMIUM MEMBERSHIP In addition to these two MEMBER BENEFITS premium categories, US Chess has many •Rated Play for the US Chess community other categories and multi-year memberships •Print and digital copies of Chess Life (or Chess Life Kids) to suit your needs. For all of your options, •Promotional discounts on chess books and equipment see new.uschess.org/join- uschess/ or call •Helping US Chess grow the game 1-800-903-8723, option 4. www.uschess.org 1 Main office: Crossville, TN (931) 787-1234 Press and Communications Inquiries: [email protected] Advertising inquiries: (931) 787-1234, ext. 123 Tournament Life Announcements (TLAs): All TLAs should be e-mailed to [email protected] or sent to P.O. Box 3967, Crossville, TN 38557-3967 Letters to the editor: Please submit to [email protected] Receiving Chess Life: To receive Chess Life as a Premium Member, join US Chess, or enter a US Chess tournament, go to uschess.org or call 1-800-903-USCF (8723) Change of address: Please send to [email protected] Other inquiries: [email protected], (931) 787-1234, fax (931) 787-1200 US CHESS US CHESS STAFF EXECUTIVE Executive Director, Carol Meyer ext. -

Course Notes and Summary

FM Morefield’s Chess Curriculum: Course Review This PDF is intended to be used as a place to review the topics covered in the course and should not be used as a replacement. Feel free to save, print, or distribute this PDF as needed. Section 1: Background Information History ● Chess is widely assumed to have originated in India around the seventh century. ● Until the mid-1400s in Europe, chess was known as shatranj, which had different rules than modern chess. ● Some well-known authors and chess players from that time period are Greco, Lucena, and Ruy Lopez. ● The Romantic Era lasted from the late 18th century until the middle of the 19th century, and was characterized by sacrifices and aggressive play. ● Chess has widely been considered a sport since the late 1800s, when the World Chess Championship was organized for the first time. Other ● Chess is considered a game of planning and strategy because it is a game with no hidden information, where you and your opponent have the same pieces, so there is no luck. ● Studying chess seriously can bring you many benefits, but simply playing it won’t make you smarter. Section 2: Rules of the Game Setting Up the Board ● There are sixty-four squares on the board, and thirty-two pieces (sixteen per player). ● Each player’s pieces are made up of eight pawns, two knights, two bishops, two rooks, a queen, and a king. ● There are two players, Black and White. White moves first. ● If you’re using a physical board, rotate the board until there is a light square on the bottom right for each player. -

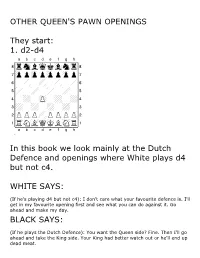

OTHER QUEEN's PAWN OPENINGS They Start: 1. D2-D4 XABCDEFGH

OTHER QUEEN'S PAWN OPENINGS They start: 1. d2-d4 XABCDEFGH 8rsnlwqkvlntr( 7zppzppzppzpp' 6-+-+-+-+& 5+-+-+-+-% 4-+-zP-+-+$ 3+-+-+-+-# 2PzPP+PzPPzP" 1tRNvLQmKLsNR! Xabcdefgh In this book we look mainly at the Dutch Defence and openings where White plays d4 but not c4. WHITE SAYS: (If he's playing d4 but not c4): I don't care what your favourite defence is. I'll get in my favourite opening first and see what you can do against it. Go ahead and make my day. BLACK SAYS: (If he plays the Dutch Defence): You want the Queen side? Fine. Then I'll go ahead and take the King side. Your King had better watch out or he'll end up dead meat. XABCDEFGHY 8rsnlwq-trk+( 7zppzp-vl-zpp' The Classical Dutch. 6-+-zppsn-+& Black's plans are to play e6-e5 or to 5+-+-+p+-% attack on the King side with moves like 4-+-+-+-+$ Qd8-e8, Qe8-h5, g7-g5, g5-g4. White 3+-+-+-+-# will try to play e2-e4, open the e-file 2-+-+-+-+" and attack Black's weak e-pawn. For this reason he will usually develop his 1+-+-+-+-! King's Bishop on g2. xabcdefghy xABCDEFGH 8rsnlwq-trk+( 7zpp+-+-zpp' The Dutch Stonewall. 6-+pvlpsn-+& Black gains space but leaves a 5+-+p+p+-% weakness on e5. He can either play for 4-+-+-+-+$ a King side attack, again with Qd8-e8, 3+-+-+-+-# Qe8-h5, g7-g5, or play in the centre 2-+-+-+-+" with b7-b6 and c6-c5. White will aim to control or occupy the e5 square with a 1+-+-+-+-! Knight while trying to break with e2-e4. -

Should Chess Players Learn Computer Security?

1 Should Chess Players Learn Computer Security? Gildas Avoine, Cedric´ Lauradoux, Rolando Trujillo-Rasua F Abstract—The main concern of chess referees is to prevent are indeed playing against each other, instead of players from biasing the outcome of the game by either collud- playing against a little girl as one’s would expect. ing or receiving external advice. Preventing third parties from Conway’s work on the chess grandmaster prob- interfering in a game is challenging given that communication lem was pursued and extended to authentication technologies are steadily improved and miniaturized. Chess protocols by Desmedt, Goutier and Bengio [3] in or- actually faces similar threats to those already encountered in der to break the Feige-Fiat-Shamir protocol [4]. The computer security. We describe chess frauds and link them to their analogues in the digital world. Based on these transpo- attack was called mafia fraud, as a reference to the sitions, we advocate for a set of countermeasures to enforce famous Shamir’s claim: “I can go to a mafia-owned fairness in chess. store a million times and they will not be able to misrepresent themselves as me.” Desmedt et al. Index Terms—Security, Chess, Fraud. proved that Shamir was wrong via a simple appli- cation of Conway’s chess grandmaster problem to authentication protocols. Since then, this attack has 1 INTRODUCTION been used in various domains such as contactless Chess still fascinates generations of computer sci- credit cards, electronic passports, vehicle keyless entists. Many great researchers such as John von remote systems, and wireless sensor networks. -

Npcc Fall Open Turns

The PENNSWOODPUSHER November 2003 A Quarterly Publication of the Pennsylvania State Chess Federation "The Ideal Socialism" Bill Ruth, the Ruth Opening, and Bill Ruth − Isidor Turover [D00] Correspondence Chess Philadelphia−Washington telephone match, November 25, 1922 1.d4 ¤f6 2.¥g5 In recent years the opening variations 1.d4 d5 2.Bg5 and 1.d4 Nf6 2.Bg5, commonly known as the Trompowsky opening after the XIIIIIIIIY Brazilian chess master Octavio Siqueiro F. Trompowsky, have become 9rsnlwqkvl-tr0 popular with many chessplayers at all levels of playing ability. The chief proponent of the Trompowsky, or the "Tromp" as fans call it, 9zppzppzppzpp0 during the past decade and a half has been the talented British Grandmaster Julian Hodgson, who uses it as a mainstay of his opening 9-+-+-sn-+0 repertoire. 9+-+-+-vL-0 Grandmaster Joe Gallagher, writing in his book The Trompowsky (The Chess Press, 1998) suggests renaming the Trompowsky opening to 9-+-zP-+-+0 reflect Hodgson's role in promoting its use at the highest level, 9+-+-+-+-0 although even Gallagher admits "the Hodgson-Trompowsky Attack is such a mouthful that I fear it will never happen." What Gallagher and 9PzPP+PzPPzP0 others are overlooking is that the opening has another name for another popularizer, at least in the United States. The talented and free-thinking 9tRN+QmKLsNR0 Philadelphia chess master and Pennsylvania State Chess Champion William Allan Ruth (1886-1975) first began surprising opponents with xiiiiiiiiy 2...d5 3.¤d2 c6 4.¤gf3 £b6 5.¥xf6 exf6 6.b3 ¥b4 7.e3 ¥f5 the second move Queen's Bishop sortie in the early 1920's. -

Four Opening Systems to Start with a Repertoire for Young Players from 8 to 80

Four opening systems to start with A repertoire for young players from 8 to 80. cuuuuuuuuC cuuuuuuuuC (rhb1kgn4} (RHBIQGN$} 70p0pDp0p} 7)P)w)P)P} 6wDwDwDwD} 6wDwDwDwD} 5DwDw0wDw} 5dwDPDwDw} &wDwDPDwD} &wDwDwdwD} 3DwDwDwDw} 3dwDpDwDw} 2P)P)w)P)} 2p0pdp0p0} %$NGQIBHR} %4ngk1bhr} v,./9EFJMV v,./9EFJMV cuuuuuuuuC (RHBIQGw$} 7)P)Pdw)P} &wDw)wDwD} 6wDwDwHwD} 3dwHBDNDw} 5dwDw)PDw} 2P)wDw)P)} &wDwDp0wD} %$wGQ$wIw} 3dwDpDwDw} v,./9EFJMV 2p0pdwdp0} %4ngk1bhr} vMJFE9/.,V A public domain e-book. [Summary Version]. Dr. David Regis. Exeter Chess Club. - 1 - - 2 - Contents. Introduction................................................................................................... 4 PLAYING WHITE WITH 1. E4 E5 ..................................................................................... 6 Scotch Gambit................................................................................................ 8 Italian Game (Giuoco Piano)........................................................................10 Two Knights' Defence ...................................................................................12 Evans' Gambit...............................................................................................14 Petroff Defence.............................................................................................16 Latvian Gambit..............................................................................................18 Elephant Gambit 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 d5.............................................................19 Philidor