Bhutan's Unique Transition to Democracy and Its Challenges*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View English PDF Version

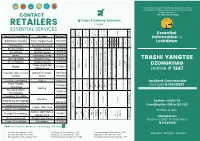

on ” 1247 17608432 17343588 Please stay alert. Chairperson His Majesty The King Hotline # 4141 Essential Lockdown Eastern COVID-19 Information Stay Home - Stay Safe - Save Lives DZONGKHAG Hotline # Dzongda Incident Commander Eastern COVID-19 Task Force Coordination Office (ECCO) It will undo everything that we have achieved so far. “ A careless person’s mistake will undo all our efforts. TRASHI YANGTSE Name Contact # Zone (Yangtse) Delivery time Delivery Day Order Day Rigney (Rigney including Hospital, RNR, NSC, BOD, 17641121 NRDCL ) 8:00 AM to 12:00 17834589/77218 PM 454 Baechen SATURDAY Retailers 17509633 SUNDAY ( 7:00 AM to 17691083 Main Town (below Dzong and Choeten Kora 12:00 PM to 3:00 6:00 PM) 17818250 area) PM 17282463 Baylling (above Dzong, including Rinchengang till 3:00 PM to 6:00 17699183 BCS) PM 6:00 AM to 17696122 Baylling, Baechen, Rigney and Main Town THURSDAY Vendors 5:00PM ( SATURDAY 6:00 AM to 6:00 Agriculture 6:00 AM to 17302242 From Serkhang Chu till Choeten Kora PM) 5:00PM 6:00 AM to MONDAY 17874349 Rigney & Baechen Zone (Yangtse and Doksum) THURSDAY Yangtse Vendors 5:00PM WEDNESDAY & SATURDAY ( Jomotshangkha Drungkhag -1210 Nganglam Drungkhag - 1195 Samdrupcholing Drungkhkag - 1191 Livestock 6:00 AM to 6:00 AM to 6:00 17532906 Main Town & Baylling Zone PM) 5:00PM TUESDAY & 77885806/77301 2:00 PM to 5:00 LPG Delivery Yangtse Throm TUESDAY & FRIDAY FRIDAY ( 9:00 AM 070 PM to 1:00 PM) Order & Delivery Schedule 17500690 FRIDAY ( Meat Shop Yangtse Throm 7:00 AM to 1:00PM SATURDAY 6:00 AM to 6:00 77624407 PM) Pharmacy 17988376 Doksum & Yangtse Throm As & when As & When / # 3 9 1 3 3 1 3 9 8 9 0 1 6 7 2 8 5 3 6 9 3 8 3 6 8 5 8 2 4 8 5 2 7 t 5 0 7 5 6 0 4 6 5 4 4 1 5 0 8 5 1 2 1 5 c 7 8 9 2 5 9 3 9 4 9 4 6 2 1 7 7 8 8 1 3 a 5 5 0 7 4 2 4 t 0 3 9 5 7 8 9 9 0 6 1 4 8 7 8 5 6 5 3 7 n 5 8 6 6 3 2 6 5 5 8 8 6 8 8 4 4 8 9 5 8 o 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 6 7 7 7 7 7 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 C 1 . -

Translation Role of Bhutanese Media in Democracy: Case Study of the 2013 General Election

Translation Role of Bhutanese Media in Democracy: Case Study of the 2013 General Election Keywords: Bhutan, Monarchy, Democracy, Information Society, Media Hitoshi FUJIWARA, Waseda University. Abstract The Kingdom of Bhutan, located in the Himalayas, closed its doors to foreign countries until the 1960s. After it reopened, Bhutan was a modern state for half a century. In 2008, the King of Bhutan decided to relinquish his power and democratize the country. It was an unprecedented event in history. On the other hand, there was no mass media in this tiny country until the 1990s. In 1999, the King lifted the ban on information technology such as television and the Internet. It was a rare case where television broadcasting and Internet services commenced at the same time. This study illustrates the history of democracy and the media in Bhutan and examines the correlation between them. Before commencing with such an examination, the theoretical stream of the relationship between democracy and the media in modern history should be reviewed. The primary section of this paper comprises field research and analysis regarding the National Assembly election of Bhutan in 2013, as a case study of the practice of democracy. The research questions are as follows: ‘What was the role of Bhutanese media in this election?’; ‘What kind of information led Bhutanese voters to decision making?’ In conclusion, the theoretical model and the Bhutanese practical model of the relationship between the government, media, and citizens are compared. This comparison shows the progress of democracy and the role of the media in modern-day Bhutan. 16 Journal of Socio-Informatics Vol. -

The Next Generation Bhutan Foundation Annual Report 2016

The Next Generation Bhutan Foundation Annual Report 2016 Our nation’s vision can only be fulfilled if the scope of our dreams and aspirations are matched by the reality of our commitment to nurturing our future citizens. —His Majesty the King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck Table of Contents 4 A time to invest in the Future: Letters from our Co-Chairs and President 8 Youth citizen scientists research how environment responds to climate change 10 Tiger, tiger, burning bright! 13 How solving a community problem can protect snow leopards 15 Bhutan’s history, my history: A student explains the importance of cultural heritage 16 Teaching the next generation of health-care workers 18 Young medical professionals take health care to mountains, glaciers, and beyond 21 Specialized training means better services for children with disabilities 23 How simple agricultural innovation can provide hope 24 How the young and old bring a community back to life 26 Civil society organizations play important role in youth participation 29 Our Partners 30 Bhutan Foundation Grants Fiscal Year 2016 34 Financial Overview 36 Ways to Give 38 Our Team Table of Contents 4 A time to invest in the Future: Letters from our Co-Chairs and President 8 Youth citizen scientists research how environment responds to climate change 10 Tiger, tiger, burning bright! 13 How solving a community problem can protect snow leopards 15 Bhutan’s history, my history: A student explains the importance of cultural heritage 16 Teaching the next generation of health-care workers 18 Young medical professionals take health care to mountains, glaciers, and beyond 21 Specialized training means better services for children with disabilities 23 How simple agricultural innovation can provide hope 24 How the young and old bring a community back to life 26 Civil society organizations play important role in youth participation 29 Our Partners 30 Bhutan Foundation Grants Fiscal Year 2016 34 Financial Overview 36 Ways to Give 38 Our Team A Time to Invest . -

DRUK Journal – Democracy in Bhutan – Spring 2018

Spring 2018 Volume 4, Issue 1 The Druk Journal འབྲུག་୲་䝴ས་䝺བ། ©2018 by The Druk Journal All rights reserved The views expressed in this publication are those of the contributors and not necessarily of The Druk Journal. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise, without permission from the publisher. ISSN 2411-6726 This publication is supported by DIPD and Open Society Foundations A Bhutan Centre for Media and Democracy Publication PO Box 1662, Thimphu, Bhutan www.bcmd.bt/www.drukjournal.bt Printed at Kuensel Corporation Ltd., Thimphu, Bhutan Dzongkha title calligraphy: Yonten Phuntsho Follow us on Facebook and Twitter འབྲུག་୲་དམངས་གཙོ荲་宱་譲མ། Democratisation of Bhutan www.drukjournal.bt The Druk Journal འབྲུག་୲་䝴ས་䝺བ། Contents Introduction 1 Editorial 2 DEMOCRACY IN BHUTAN Political Parties in the 21st Century Bjørn Førde 3 Democracy in Bhutan Dr Brian C. Shaw 14 DEMOCRACY DECENTRALISed Dhar from the Throne : an Honour and a Responsibility Kinley Dorji, Tashi Pem 24 The Micro Effect of Democratisation in Rural Bhutan Tshering Eudon 28 The Thromde Elections – an Inadequate Constituency? Ugyen Penjore 38 POLITicS OF DEMOCRACY Socio-economic Status and Electoral Participation in Bhutan Kinley 46 National Interest Versus Party Interest: What Former Chimis Think of Parliamentary Discussions Tashi Dema 59 The Bhutanese Politicians Kesang Dema 66 Youth and Politics in an Evolving Democracy Siok Sian -

2Nd Parliament of Bhutan 10Th Session

2ND PARLIAMENT OF BHUTAN 10TH SESSION Resolution No. 10 PROCEEDINGS AND RESOLUTION OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF BHUTAN (November 15 - December 8, 2017) Speaker: Jigme Zangpo Table of Content 1. Opening Ceremony..............................................................................1 2. Introduction and Adoption of Bill......................................................5 2.1 Motion on the First and Second Reading of the Royal Audit Bill 2017 (Private Member’s Bill)............................................5 2.2 Motion on the First and Second Reading of the Narcotic Drugs, Psychotropic Substances and Substance Abuse (Amendment) Bill of Bhutan 2017 (Urgent Bill)...............................6 2.3 Motion on the First and Second Reading of the Tourism Levy Exemption Bill of Bhutan 2017................................................7 3. Deliberation on the petition submitted by Pema Gatshel Dzongkhag regarding the maximum load carrying capacity for Druk Satiar trucks.........................................................10 4. Question Hour: Group A - Questions relevant to the Prime Minister, Ministry of Information and Communications, and Ministry of Home and Cultural Affairs......................................12 5. Ratification of Agreement................................................................14 5.1 Agreement Between the Royal Government of Bhutan and the Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the prevention of Fiscal Evasion with respect to Taxes of Income..........................14 -

The Kingdom of Bhutan Health System Review

Health Sy Health Systems in Transition Vol. 7 No. 2 2017 s t ems in T r ansition Vol. 7 No. 2 2017 The Kingdom of Bhutan Health System Review The Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (the APO) is a collaborative partnership of interested governments, international agencies, The Kingdom of Bhutan Health System Review foundations, and researchers that promotes evidence-informed health systems policy regionally and in all countries in the Asia Pacific region. The APO collaboratively identifies priority health system issues across the Asia Pacific region; develops and synthesizes relevant research to support and inform countries' evidence-based policy development; and builds country and regional health systems research and evidence-informed policy capacity. ISBN-13 978 92 9022 584 3 Health Systems in Transition Vol. 7 No. 2 2017 The Kingdom of Bhutan Health System Review Written by: Sangay Thinley: Ex-Health Secretary, Ex-Director, WHO Pandup Tshering: Director General, Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Health Kinzang Wangmo: Senior Planning Officer, Policy and Planning Division, Ministry of Health Namgay Wangchuk: Chief Human Resource Officer, Human Resource Division, Ministry of Health Tandin Dorji: Chief Programme Officer, Health Care and Diagnostic Division, Ministry of Health Tashi Tobgay: Director, Human Resource and Planning, Khesar Gyalpo University of Medical Sciences of Bhutan Jayendra Sharma: Senior Planning Officer, Policy and Planning Division, Ministry of Health Edited by: Walaiporn Patcharanarumol: International Health Policy Program, Thailand Viroj Tangcharoensathien: International Health Policy Program, Thailand Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies i World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia. The Kingdom of Bhutan health system review. -

56. Parliament Security Office

VII. PARLIAMENT SECURITY SERVICE 56. PARLIAMENT SECURITY OFFICE 56.1 The Parliament Security Service of Rajya Sabha Secretariat looks after the security set up in the Parliament House Complex. Director (Security) of the Rajya Sabha Secretariat exercises security operational control over the Parliament Security Service in the Rajya Sabha Sector under the administrative control of the Rajya Sabha Secretariat. Joint Secretary (Security), Lok Sabha Secretariat is the overall in-charge of security operations of entire Parliament Security including Parliament Security Services of both the Secretariats, Delhi Police, Parliament Duty Group (PDG) and all the other allied security agencies operating within the Complex. Parliament Security Service being the in- house security service provides proactive, preventive and protective security to the VIPs/VVIPs, building & its incumbents. It is solely responsible for managing the access control & regulation of men, material and vehicles within the historical and prestigious Parliament House Complex. Being the in-house security service its prime approach revolves around the principles of Access Control based on proper identification, verification, authentication & authorization of men and material resources entering into the Parliament House Complex with the help of modern security gadgets. The threat perception has been increasing over the years due to manifold growth of various terrorist organizations/outfits, refinement in their planning, intelligence, actions and surrogated war-fare tactics employed by organizations sponsoring and nourishing terrorists. New security procedures have been introduced into the security management to counter the ever-changing modus operandi of terrorist outfits/ individuals posing severe threat to the Parliament House Complex and its incumbent VIPs. This avowed objective is achieved in close coordination with various security agencies such as Delhi Police (DP), Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), Intelligence Bureau (IB), Special Protection Group (SPG) and National Security Guard (NSG). -

Sebuah Kajian Pustaka

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 3, March 2018 ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gate as well as in Cabell‟s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Democracy: Present and Future in Bhutan Dr. DHARMENDRA MIDDLE SCHOOL TEACHER U.M.S CHAINPUR THARTHARI,NALANDA Abstract Democracy has come a long way from the Greek ideas of Demos and Kratos and in fact this journey in the tiny Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan since 2008 seems to be one of a regime initiated one. It holds all the trappings of being depicted as yet another model of guided democracy, like the ones prevalent in Turkey (since Ataturk), in Pakistan under the martial law administrators as well as under Pervez Musharraf, Indonesia (under Ahmed Sukarno) and others where, democracy is and was looked upon as an institution under the protection of the armed forces. And this incident made way to autocracy in those countries. In Bhutan, the custodian appears to be the monarchy and the monarchs themselves. The framers of the 2008 constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan makes every effort to insulate their document from political quagmire by putting in place certain qualifications namely like that candidates contesting the poll should be graduates only, making way for the technocrats to run for the elected offices. For the present time this guided democracy seems to continue without much of a problem but in the future it might give way to some other form or perhaps political turmoil. -

Democracy in Bhutan Is Truly a Result of the Desire, Structural Changes Within the Bhutanese Aspiration and Complete Commitment of the Polity

MARCH 2010 IPCS Research Papers DDeemmooccrraaccyy iinn BBhh uuttaann AAnn AAnnaallyyssiiss ooff CCoonn ssttiittuuttiioonnaall CChhaannggee iinn aa BBuuddddhhiisstt MMoonnaarrcc hhyy Marian Gallenkamp Marian Gallenkamp IInnssttiittuuttee ooff PPeeaaccee aanndd CCoonnfflliicctt SSttuuddiieess NNeeww DDeellhh1 ii,, IINNDDIIAA Copyright 2010, Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies (IPCS) The Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies is not responsible for the facts, views or opinion expressed by the author. The Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies (IPCS), established in August 1996, is an independent think tank devoted to research on peace and security from a South Asian perspective. Its aim is to develop a comprehensive and alternative framework for peace and security in the region catering to the changing demands of national, regional and global security. Address: B 7/3 Lower Ground Floor Safdarjung Enclave New Delhi 110029 INDIA Tel: 91-11-4100 1900, 4165 2556, 4165 2557, 4165 2558, 4165 2559 Fax: (91-11) 4165 2560 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ipcs.org CONTENTS I. Introduction.................................................................................................2 II. Constitutional Change: A Comprehensive Analysis ..................................3 III. Conclusion: Bhutan a Unique Case?...................................................... 16 VI. Bibliography............................................................................................ 19 I. Introduction “Democracy in Bhutan is truly a result of the desire, structural changes within the Bhutanese aspiration and complete commitment of the polity. While the historical analysis might monarchy to the well-being of the people and the appear to be excessive, it nevertheless is an country” important task to fully understand the uniqueness of the developments in Bhutan. (Chief Justice of Bhutan, Lyonpo Sonam Democratic transition does not happen Tobgye, 18 July 2008) overnight; it is usually a long process of successive developments. -

Reports Published Under the Icpe Series

INDEPENDENT COUNTRY PROGRAMME EVALUATION OF UNDP CONTRIBUTION UNDP OF EVALUATION PROGRAMME COUNTRY INDEPENDENT Independent Evaluation Office INDEPENDENT COUNTRY PROGRAMME EVALUATION OF UNDP CONTRIBUTIONBHUTAN BHUTAN HUMAN DEVELOPMENT effectiveness COORDINATI efficiency COORDINATION AND PARTNERSHIP sust NATIONAL OWNERSHIP relevance MANAGING FOR sustainability MANAGING FOR RESULTS responsivene DEVELOPMENT responsiveness NATIONAL OWNER NATIONAL OWNERSHIP effectiveness COORDINATI efficiency COORDINATION AND PARTNERSHIP sust NATIONAL OWNERSHIP relevance MANAGING FOR sustainability MANAGING FOR RESULTS responsivene HUMAN DEVELOPMENT effectiveness COORDINATI INDEPENDENT COUNTRY PROGRAMME EVALUATION OF UNDP CONTRIBUTION BHUTAN Independent Evaluation Office, April 2018 United Nations Development Programme REPORTS PUBLISHED UNDER THE ICPE SERIES Afghanistan Gabon Papua New Guinea Albania Georgia Paraguay Algeria Ghana Peru Angola Guatemala Philippines Argentina Guyana Rwanda Armenia Honduras Sao Tome and Principe Bangladesh India Senegal Barbados and OECS Indonesia Serbia Benin Iraq Seychelles Bhutan Jamaica Sierra Leone Bosnia and Herzegovina Jordan Somalia Botswana Kenya Sri Lanka Brazil Kyrgyzstan Sudan Bulgaria Lao People’s Democratic Republic Syria Burkina Faso Liberia Tajikistan Cambodia Libya Tanzania Cameroon Malawi Thailand Chile Malaysia Timor-Leste China Maldives Togo Colombia Mauritania Tunisia Congo (Democratic Republic of) Mexico Turkey Congo (Republic of) Moldova (Republic of) Uganda Costa Rica Mongolia Ukraine Côte d’Ivoire Montenegro -

Political Highlights Economic Trend 2017 2018 2019* 2020^ 2021^ 2.4

Political Highlights Government type Constitutional monarchy Chief of state King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck Head of government Prime Minister Lotay Tshering Elections/appointments The cabinet is nominated by the monarch in consultation with the prime minister and approved by the National Assembly. Next election for the National Council (upper council) and National Assembly (lower council) scheduled for 2023. Legal system Civil law Legislative branch Bicameral Parliament (25-seat National Council and 47-seat National Assembly) Major political parties Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa; Druk Phuensum Tshogpa; People's Democratic Party. Economic Trend Economic Indicators 2017 2018 2019* 2020^ 2021^ Nominal GDP (USD bn) 2.4 2.6 2.8 3 3.2 Real GDP growth (%) 6.3 3.7 5.3 2.7 2.9 GDP per capita (USD) 2,938 3,160 3,423 3,533 3,787 Inflation (%) 5.4 2.7 2.6 3.1 3.5 Current account balance (% of GDP) -23.6 -19.5 -23.1 -21.3 -20.2 General government debt (% of GDP) 108 102.4 108.6 105.7 101 * Estimate ^ Forecast Hong Kong Total Exports to Bhutan (HK$ mn) Hong Kong Total Exports to Bhutan Year Bolivia World (World) (Bhutan) 2010 6 3,031,019 4500000 35 2011 5 3,337,253 4000000 2012 10 3,434,346 30 2013 31 3,559,686 3500000 2014 10 3,672,751 25 2015 6 3,605,279 3000000 World 2016 8 3,588,247 2500000 20 2017 21 3,875,898 Bhutan (HK$ (HK$ mn) 2018 11 4,158,106 2000000 15 2019 30 3,988,685 1500000 10 1000000 5 500000 0 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Hong Kong Exports to Bhutan by Product Hong Kong Exports to Bhutan by Product (2019) (% share) -

Bhutan Country Report BTI 2018

BTI 2018 Country Report Bhutan This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018. It covers the period from February 1, 2015 to January 31, 2017. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — Bhutan. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2018 | Bhutan 3 Key Indicators Population M 0.8 HDI 0.607 GDP p.c., PPP $ 8744 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.3 HDI rank of 188 132 Gini Index 38.8 Life expectancy years 69.8 UN Education Index 0.504 Poverty3 % 14.5 Urban population % 39.4 Gender inequality2 0.477 Aid per capita $ 123.5 Sources (as of October 2017): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2017 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2016. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary The second national democratic election went smoothly in 2013 and confirmed Bhutan’s growing familiarity with and acceptance of democracy.