KAS International Reports 04/2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

26Th March 2021 Golden Jubilee of Independence Bangladesh

6 BANGLADESH FRIDAY-SUNDAY, MARCH 26-28, 2021 26th March 2021 Golden Jubilee of Independence Bangladesh Our constitution was made on the basis of the spirit of the liberation war under his direction within just 10 months. In just three and a half years, he took war-torn Bangladesh to the list of least developed country. While Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib was advancing to build an exploitation-deprivation-free non-communal democratic 'Sonar Bangla' overcoming all obstacles, the anti-liberation forces brutally killed him along with most of his family members on 15 August 1975. After the assassination of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib, the development and progress of Bangladesh came to a halt. The politics of killing, coup and conspiracy started in our beloved motherland. The assassins and their accomplices promulgated the 'Indemnity Ordinance' to block the trial of this heinous murder in the history. Getting the public mandate in 1996, Bangladesh Awami League formed the government after long 21 years. After assuming the office, we took the initiatives to establish H.E. Mr. Md. Abdul Hamid H.E. Sheikh Hasina Bangladesh as a self-respectful in the comity of Hon’ble President of Hon’ble Prime Minister of nations. Through the introduction of social Bangladesh Bangladesh safety-net programs, poor and marginalized people are brought under government allowances. We made the country self-sufficient Today is 26th March, our Independence and Today is the 26th March- our great in food production with special emphasis on National Day. This year we are celebrating the Independence Day. Bangladesh completes 50 agricultural production. The Ganges Water Sharing Treaty was signed with India in 1996. -

Predators 2021 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 PREDATORS 2021 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Azerbaijan 167/180* Eritrea 180/180* Isaias AFWERKI Ilham Aliyev Born 2 February 1946 Born 24 December 1961 > President of the Republic of Eritrea > President of the Republic of Azerbaijan since 19 May 1993 since 2003 > Predator since 18 September 2001, the day he suddenly eliminated > Predator since taking office, but especially since 2014 his political rivals, closed all privately-owned media and jailed outspoken PREDATORY METHOD: Subservient judicial system journalists Azerbaijan’s subservient judicial system convicts journalists on absurd, spurious PREDATORY METHOD: Paranoid totalitarianism charges that are sometimes very serious, while the security services never The least attempt to question or challenge the regime is regarded as a threat to rush to investigate physical attacks on journalists and sometimes protect their “national security.” There are no more privately-owned media, only state media assailants, even when they have committed appalling crimes. Under President with Stalinist editorial policies. Journalists are regarded as enemies. Some have Aliyev, news sites can be legally blocked if they pose a “danger to the state died in prison, others have been imprisoned for the past 20 years in the most or society.” Censorship was stepped up during the war with neighbouring appalling conditions, without access to their family or a lawyer. According to Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh and the government routinely refuses to give the information RSF has been getting for the past two decades, journalists accreditation to foreign journalists. -

Bangladesh Beckons 2020

CONTENTS 1 Message from Honʼble President 2 Message from Honʼble Prime Minister 3 Message from Honʼble Foreign Minister 4 Message from Honʼble State Minister for Foreign Affairs 5 A Few Words from the High Commissioner 8 Bangabandhu in Timeline 12 Bangabandhu: The Making of a Great Leader 15 Bangabandhu: A Poet of Politics 18 The Greatest Speech of the Greatest Bangali 21 The Political Philosophy of Bangabandhu 25 Bangabandhu's Thoughts on Economic Development 28 Foreign Policy in Bangabandhu's Time 31 People-centric Education Policy of Bangabandhu Chief Editor Photos His Excellency External Publicity Wing, 34 Bangabandhu, Who Set the Tone of Md. Mustafizur Rahman Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Agricultural Revolution Dhaka Official website of Mujib Executive Editor Borsho Celebration Bangabandhu and his Policy of Health for All Committee 37 Md. Toufiq-ur-Rahman (https://mujib100.gov.bd/) Collections from Public 41 Bangabandhu: What the World Needs to Know Editorial Team Domain A.K.M. Azam Chowdhury Learnings from Bangabandhu's Writings Mohammad Ataur Rahman Portraits 45 Sabbir Ahmed Shahabuddin Ahmed Md. Rafiqul Islam Ahmed Shamsuddoha 47 What Lessons We Can Learn from Morioum Begum Shorna Moniruzzaman Monir Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Shahjahan Ahmed Bikash Cover Photo Kamaluddin Painting of Ahmed Samiran Chowdhury 50 Bangabandhu and Nelson Mandela: Samsuddoha Drawing a Parallel Courtesy of Hamid Group Design and Printing Kaleido Pte Ltd 53 Lee Kuan Yew and Sheikh Mujib: Article Sources 63 Ubi Avenue 1, #06-08B 63@Ubi, Singapore 408937 Titans of Tumultuous Times Collections from Public Domain M: 9025 7929 T: 6741 2966 www.kaleidomarketing.com Write ups by the High 55 Bangabandhu in the Eyes of World Leaders Commission 57 Tributes to Bangabandhu in Pictures Property of the High Commission of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh #04-00/ #10-00, Jit Poh Building, 19 Keppel Road, 58 Bangabandhu Corner in Pictures Singapore 089058, Tel. -

Emerging India? - Google Docs

1/11/2019 Reemerging India? - Google Docs Centre for Public Policy Research Independent. In-depth. Insightful (Re)Emerging India? Article by Gazi Hassan Image courtesy AP With the forces of globalisation blurring the lines between sovereignty and interdependence, the world is at a point where bilateralism and multilateralism have become the need of the hour. In the international system, there exists a dynamic relationship between the nations, where traditional enemies can become allies and allies can turn hostile to each other. The region of South Asia is emerging as a pivot for changing international politics in a significant manner. India being the largest country both in terms of area and population in the region has to sustain its dominance by exerting soft power to wean away the rising popularity of China. The Chinese influence has been on the rise and in order to cope with it, India has to carefully frame its policy to protect its national interests in the South Asian region. The political developments in various countries of the region highlighted below and India’s response to them will make grounds for robustness in policy making. 1 Centre for Strategic Studies https://docs.google.com/document/d/1Gs3u3vWbRROOxjAOSxQvLzMjPpRca_iR1Ps3r-rlsHI/edit# 1/5 1/11/2019 Reemerging India? - Google Docs Centre for Public Policy Research Independent. In-depth. Insightful Sri Lanka After several months of political drama, normalcy has returned to Sri Lanka. Political crisis broke out in the country in October 2018, when the sitting President Maithripala Sirisena dissolved the Parliament and dismissed his Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe on account of allegedly plotting to assassinate him and undermining national interests. -

2Nd Parliament of Bhutan 10Th Session

2ND PARLIAMENT OF BHUTAN 10TH SESSION Resolution No. 10 PROCEEDINGS AND RESOLUTION OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF BHUTAN (November 15 - December 8, 2017) Speaker: Jigme Zangpo Table of Content 1. Opening Ceremony..............................................................................1 2. Introduction and Adoption of Bill......................................................5 2.1 Motion on the First and Second Reading of the Royal Audit Bill 2017 (Private Member’s Bill)............................................5 2.2 Motion on the First and Second Reading of the Narcotic Drugs, Psychotropic Substances and Substance Abuse (Amendment) Bill of Bhutan 2017 (Urgent Bill)...............................6 2.3 Motion on the First and Second Reading of the Tourism Levy Exemption Bill of Bhutan 2017................................................7 3. Deliberation on the petition submitted by Pema Gatshel Dzongkhag regarding the maximum load carrying capacity for Druk Satiar trucks.........................................................10 4. Question Hour: Group A - Questions relevant to the Prime Minister, Ministry of Information and Communications, and Ministry of Home and Cultural Affairs......................................12 5. Ratification of Agreement................................................................14 5.1 Agreement Between the Royal Government of Bhutan and the Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the prevention of Fiscal Evasion with respect to Taxes of Income..........................14 -

56. Parliament Security Office

VII. PARLIAMENT SECURITY SERVICE 56. PARLIAMENT SECURITY OFFICE 56.1 The Parliament Security Service of Rajya Sabha Secretariat looks after the security set up in the Parliament House Complex. Director (Security) of the Rajya Sabha Secretariat exercises security operational control over the Parliament Security Service in the Rajya Sabha Sector under the administrative control of the Rajya Sabha Secretariat. Joint Secretary (Security), Lok Sabha Secretariat is the overall in-charge of security operations of entire Parliament Security including Parliament Security Services of both the Secretariats, Delhi Police, Parliament Duty Group (PDG) and all the other allied security agencies operating within the Complex. Parliament Security Service being the in- house security service provides proactive, preventive and protective security to the VIPs/VVIPs, building & its incumbents. It is solely responsible for managing the access control & regulation of men, material and vehicles within the historical and prestigious Parliament House Complex. Being the in-house security service its prime approach revolves around the principles of Access Control based on proper identification, verification, authentication & authorization of men and material resources entering into the Parliament House Complex with the help of modern security gadgets. The threat perception has been increasing over the years due to manifold growth of various terrorist organizations/outfits, refinement in their planning, intelligence, actions and surrogated war-fare tactics employed by organizations sponsoring and nourishing terrorists. New security procedures have been introduced into the security management to counter the ever-changing modus operandi of terrorist outfits/ individuals posing severe threat to the Parliament House Complex and its incumbent VIPs. This avowed objective is achieved in close coordination with various security agencies such as Delhi Police (DP), Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), Intelligence Bureau (IB), Special Protection Group (SPG) and National Security Guard (NSG). -

Reports Published Under the Icpe Series

INDEPENDENT COUNTRY PROGRAMME EVALUATION OF UNDP CONTRIBUTION UNDP OF EVALUATION PROGRAMME COUNTRY INDEPENDENT Independent Evaluation Office INDEPENDENT COUNTRY PROGRAMME EVALUATION OF UNDP CONTRIBUTIONBHUTAN BHUTAN HUMAN DEVELOPMENT effectiveness COORDINATI efficiency COORDINATION AND PARTNERSHIP sust NATIONAL OWNERSHIP relevance MANAGING FOR sustainability MANAGING FOR RESULTS responsivene DEVELOPMENT responsiveness NATIONAL OWNER NATIONAL OWNERSHIP effectiveness COORDINATI efficiency COORDINATION AND PARTNERSHIP sust NATIONAL OWNERSHIP relevance MANAGING FOR sustainability MANAGING FOR RESULTS responsivene HUMAN DEVELOPMENT effectiveness COORDINATI INDEPENDENT COUNTRY PROGRAMME EVALUATION OF UNDP CONTRIBUTION BHUTAN Independent Evaluation Office, April 2018 United Nations Development Programme REPORTS PUBLISHED UNDER THE ICPE SERIES Afghanistan Gabon Papua New Guinea Albania Georgia Paraguay Algeria Ghana Peru Angola Guatemala Philippines Argentina Guyana Rwanda Armenia Honduras Sao Tome and Principe Bangladesh India Senegal Barbados and OECS Indonesia Serbia Benin Iraq Seychelles Bhutan Jamaica Sierra Leone Bosnia and Herzegovina Jordan Somalia Botswana Kenya Sri Lanka Brazil Kyrgyzstan Sudan Bulgaria Lao People’s Democratic Republic Syria Burkina Faso Liberia Tajikistan Cambodia Libya Tanzania Cameroon Malawi Thailand Chile Malaysia Timor-Leste China Maldives Togo Colombia Mauritania Tunisia Congo (Democratic Republic of) Mexico Turkey Congo (Republic of) Moldova (Republic of) Uganda Costa Rica Mongolia Ukraine Côte d’Ivoire Montenegro -

PM Modi, Hasina Agree to Remove Non-Tariff Barriers in Trade Five Mous Signed Clude Ones in Areas Such As Dis- Ment Said

PM Modi, Hasina agree to remove non-tariff barriers in trade Five MoUs signed clude ones in areas such as dis- ment said. The two Prime Minis- revitalise and modernize the aster management, bilateral ters agreed that in the spirit of jute sector through manufac- covering a number trade remedies, ICT Equipment liberalising trade between the turing of value added and diver- areas of bilateral supplies and establishment of two countries, Bangladesh sified jute products,” the state- sports facilities. There was also Standards and Testing Institute ment said. cooperation an MoU between Bangladesh (BSTI) and the Bureau of Indian To resolve the contentious is- National Cadet Corps and Na- Standards (BIS) would collabor- sue of water sharing, the two OUR BUREAU tional Cadet Corps of India. ate for the capacity building leaders directed their respect- New Delhi, March 28 Prime Minister Modi had a and development of testing ive Ministries of Water Re- Prime Minister Narendra Modi series of engagements during and Lab facilities, the statement sources to work towards an and his Bangladeshi counter- his Bangladesh visit including pointed out. early conclusion of the Frame- part Sheikh Hasina have agreed meetings with political leaders Both sides also emphasised work of Interim Agreement on on the need to remove non-tar- of opposition parties and the on expeditious conclusion of sharing of waters of six com- iff barriers to increase bilateral Foreign Minister. He also Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bangladeshi counterpart the ongoing joint study on the mon rivers, namely, Manu, trade. They also decided to fast- offered prayers at the Hari Sheikh Hasina during the inauguration of various projects in Dhaka PTI prospects of entering into a Muhuri, Khowai, Gumti, Dharla track the on-going joint study Mandir in Orakandi. -

Sheikh Hasina Hon Ble Prime Minister Government of the People S Republic of Bangladesh

73rd Session of the United Nations General Assembly Address by Sheikh Hasina Hon ble Prime Minister Government of the People s Republic of Bangladesh The United Nations New York 27 September 2018 Bismillahir Rahmanir Rahim Madam President, As-Salamu Alaikum and good evening. Let me congratulate you on your election as the fourth female President of the UN General Assembly during its 73 years history. I assure you of my delegation’s full support in upholding your commitment to the UN. I also felicitate Mr. Antonio Guterres, UN Secretary General for his firm and courageous leadership in promoting global peace, security and sustainable development. Madam President, The theme you have chosen for this year’s session brings back some personal memories for me. Forty-four years ago, my father, the Father of the Nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman stood on this podium and said, / quote, Peace is an imperative for the survival of humanity. It represents the deepest aspirations of men and women throughout the world... The United Nations remains as the centre of hope for the future of the people in this world of sadness, misery and conflict. Unquote Madam President, My father Bangab ndhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman devoted his life for the socio¬ economic development of the people of Bangladesh. He had done so at a time when 90% of the population lived below the poverty line. Following 24 years of stmggle culminating in the victory of our Liberation War, Bangladesh gained Independence under his leadership in 1971. During this long period of struggle, he spent his time in the prison for almost 14 years. -

UN Support for Strengthening the Institutional Capacity of Parliament O F Bhutan

UN Support for Strengthening the Institutional Capacity of Parliament o f Bhutan Terms of Reference Development of Organizational Development Strategy (ODS) for the National Council & Review of ODS of the National Assembly of Bhutan 1st September - 20th September, 2009 1. INTRODUCTION With the adoption of Constitution, Bhutan is politically transformed from a unicameral to bicameral system of parliament in which all legislative powers are vested, comprising of the Druk Gyalpo, the National Council and the National Assembly. Article 10 (2) of the Constitution states that the role of the Parliament shall be “to ensure that the Government safeguards the interest of the nation and fulfils the aspirations of the people through public review of policies and issues, Bills and other legislation, and scrutiny of Sate functions”. In view of the political reforms and the need to enhance capacity at the National Council and National Assembly levels and the Secretariats, an agreement to support Strengthening the Institutional Capacity of Parliament of Bhutan was signed on 1 st June, 2009 between the Royal Government of Bhutan and UN System in Bhutan. To enable the Parliament to discharge its mandates as enshrined in the Constitution, an Organisational Development Strategy outlining our strategic direction in providing advice, support and information to the Members of Parliament, and information about the Parliamentary committees to the public and help us provide the services required for the parliamentarians to perform their functions efficiently and effectively is one of the strategic and urgent imperatives of the Parliament. This exercise will mainly concentrate on 1 developing ODS for National Council and review and update ODS of the Page National Assembly. -

Buddhism and Politics the Politics of Buddhist Relic Diplomacy Between Bangladesh and Sri Lanka

Special Issue: Buddhism and Politics Journal of Buddhist Ethics ISSN 1076-9005 http://blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/ Volume 25, 2018 The Politics of Buddhist Relic Diplomacy Between Bangladesh and Sri Lanka D. Mitra Barua Cornell University Copyright Notice: Digital copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no change is made and no alteration is made to the content. Reproduction in any other format, with the exception of a single copy for private study, requires the written permission of the author. All en- quiries to: [email protected]. The Politics of Buddhist Relic Diplomacy Between Bangladesh and Sri Lanka D. Mitra Barua 1 Abstract Buddhists in Chittagong, Bangladesh claim to preserve a lock of hair believed to be of Sakyamuni Buddha himself. This hair relic has become a magnet for domestic and transnational politics; as such, it made journeys to Colom- bo in 1960, 2007, and 2011. The states of independent Cey- lon/Sri Lanka and East Pakistan/Bangladesh facilitated all three international journeys of the relic. Diplomats from both countries were involved in extending state invita- 1 The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow, Cornell University. Email: [email protected]. The initial version of this article was presented at the confer- ence on “Buddhism and Politics” at the University of British Columbia in June 2014. It derives from the section of Buddhist transnational networks in my ongoing research project on Buddhism in Bengal. I am grateful to the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship in Buddhist Studies (administered by the American Council of Learned Societies) for its generous funding that has enabled me to conduct the re- search. -

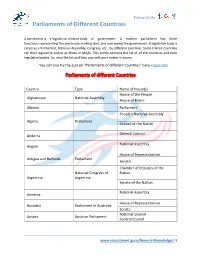

Parliaments of Different Countries

Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries A parliament is a legislative, elected body of government. A modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government. A legislative body is called as a Parliament, National Assembly, Congress, etc., by different countries. Some Islamic countries call their legislative bodies as Shora or Majlis. This article contains the list of all the countries and their legislative bodies. So, read the list and help yourself score better in exams. You can also try the quiz on “Parliaments of different Countries” here – Quiz Link Parliaments of different Countries Country Type Name of house(s) House of the People Afghanistan National Assembly House of Elders Albania Parliament People's National Assembly Algeria Parliament Council of the Nation General Council Andorra National Assembly Angola House of Representatives Antigua and Barbuda Parliament Senate Chamber of Deputies of the National Congress of Nation Argentina Argentina Senate of the Nation National Assembly Armenia House of Representatives Australia Parliament of Australia Senate National Council Austria Austrian Parliament Federal Council www.recruitment.guru/General-Knowledge/|1 Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries Azerbaijan National Assembly House of Assembly Bahamas, The Parliament Senate Council of Representatives Bahrain National Assembly Consultative Council National Parliament Bangladesh House of Assembly Barbados Parliament Senate House of Representatives National Assembly