Interpreting EVEL: Latest Station in the Conservative Party's English Journey?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Edward Leigh Onorificenza Commendatore Osi My Lords

Sir Edward Leigh Onorificenza Commendatore Osi My Lords, Ladies and Gentlemen, a very good evening and welcome to the Italian Embassy. Thank you all for coming here this evening to celebrate the presentation of the Commendatore della Stella d’Italia award, bestowed upon our friend Sir Edward Leigh by the Italian President. First I would like to start saying a few words on this prestigious award. The different ranks of the order of the Stella d’Italia are bestowed upon Italians living abroad and foreign nationals, in recognition of their special merits in fostering friendly relations and cooperation between Italy and their country of residence and the promotion of ties with Italy. Since the start of the order only 4675 Commendatori of the Italian Star have been awarded. 1 A small army of friends of Italy from the four corners of the globe. I am glad that Sir Edward’s name has now been added to this prestigious list of distinguished individuals. It is my personal honor to welcome Sir Edward Leigh to the Embassy today. Sir Edward has been member of the House of Commons since 1983 and recently won his ninth consecutive parliamentary election. As well as being a well renowned politician, Sir Edward is also a qualified barrister, he practiced in arbitration and criminal law for Goldsmiths Chambers, and has served as an Independent Financial Advisor to the Treasury. Since 2011, he has also been elected as Chairman of the Public Accounts Commission, the body which audits the National Audit Office, responsible for saving the taxpayer over £4 billion. -

![The National Audit Office, the Public Accounts Committee and the Risk Landscape in UK Public Policy Discussion Paper [Or Working Paper, Etc.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3538/the-national-audit-office-the-public-accounts-committee-and-the-risk-landscape-in-uk-public-policy-discussion-paper-or-working-paper-etc-93538.webp)

The National Audit Office, the Public Accounts Committee and the Risk Landscape in UK Public Policy Discussion Paper [Or Working Paper, Etc.]

Patrick Dunleavy, Christopher Gilson, Simon Bastow and Jane Tinkler The National Audit Office, the Public Accounts Committee and the risk landscape in UK Public Policy Discussion paper [or working paper, etc.] Original citation: Dunleavy, Patrick, Christopher Gilson, Simon Bastow and Jane Tinkler (2009): The National Audit Office, the Public Accounts Committee and the risk landscape in UK public policy. URN 09/1423. The Risk and Regulation Advisory Council, London, UK. This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/25785/ Originally available from LSE Public Policy Group Available in LSE Research Online: November 2009 © 2009 the authors LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. The National Audit Office, the Public Accounts Committee and the Risk Landscape in UK Public Policy Patrick Dunleavy, Christopher Gilson, Simon Bastow and Jane Tinkler October 2009 The Risk and Regulation Advisory Council This report was produced in July 2009 for the Risk and Regulation Advisory Council. The Risk and Regulation Advisory Council is an independent advisory group which aims to improve the understanding of public risk and how to respond to it. -

Copy of 2008122008-Cwells-Regulated

1 donation information continues on reverse Late reported donation by regulated donees 15 February 2001 - 31 January 2008 (where data is available) Regulated donee Donor organisation Donor forename Donor surname Donor status Address 1 Address 2 Jimmy Hood MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Keith Simpson MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Cheryl Gillan MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Elfyn Llwyd MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Ian Stewart MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Ian Stewart MP Manchester Airport Plc Company PO Box 532 Town Hall John Gummer MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Christopher Beazles BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Chris Smith MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Mike Weir MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Tony Worthington MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Ian Davidson MP BAA plc Company 130 Wilton Road Paul Tyler BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Matthew Taylor MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Menzies Campbell MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Archy Kirkwood BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road David Hanson MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Colin Breed MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road David Marshall MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Mark Oaten MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Diana Wallis MEP Manchester Airport Plc Company PO Box 532 Town Hall Christopher Ruane MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Tim Loughton MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Robert Wareing MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road Robert Wareing MP Manchester Airport Plc Company PO Box 532 Town Hall John McFall MP BAA Plc Company 130 Wilton Road -

From 'Greenest Government Ever' to 'Get Rid of All the Green Crap': David Cameron, the Conservatives and the Environment

This is a repository copy of From ‘greenest government ever’ to ‘get rid of all the green crap’: David Cameron, the Conservatives and the environment. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/85469/ Version: Submitted Version Article: Carter, Neil Thomas orcid.org/0000-0003-3378-8773 and Clements, Ben (2015) From ‘greenest government ever’ to ‘get rid of all the green crap’: David Cameron, the Conservatives and the environment. British Politics. 204–225. ISSN 1746-918X https://doi.org/10.1057/bp.2015.16 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ From ‘Greenest government ever’ to ‘get rid of all the green crap’: David Cameron, the Conservatives and the Environment by Neil Carter (University of York) and Ben Clements (University of Leicester) Published in British Politics, early online April 2015. This is a post-peer-review, pre-copy-edit version of the paper. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Friday Volume 607 11 March 2016 No. 131 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Friday 11 March 2016 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2016 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 545 11 MARCH 2016 Foreign National Offenders 546 (Exclusion from the UK) Bill There are 10,442 foreign national prisoners in our House of Commons prisoners out of a total of 85,886—12% of the prison population. You will perhaps be surprised to learn, Friday 11 March 2016 Mr Speaker, that those 10,442 come not just from one, two, three, four, half a dozen or a dozen countries, but from some 160 countries from around the world. Indeed, The House met at half-past Nine o’clock 80% of the world’s nations are represented in our prisons. We are truly an internationally and culturally diverse PRAYERS nation, even in our imprisoned population. Very worryingly indeed, something like a third of them have been convicted of violent and sexual offences; a fifth have been convicted [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] of drugs offences; and others have been convicted of burglary, robbery, fraud and other serious crimes. Mr David Nuttall (Bury North) (Con): I beg to move, That the House sit in private. It is a good thing that the crimes have been detected, Question put forthwith (Standing Order No. 163), and the evidence has been gathered and these people are negatived. being punished for their offences. It is, however, completely wrong that the cost of that imprisonment should fall on British taxpayers, because these individuals—every single Foreign National Offenders (Exclusion last one of them—should be repatriated to secure detention from the UK) Bill in their country of origin, so that taxpayers from their Second Reading own countries can pay the bill for their incarceration and punishment. -

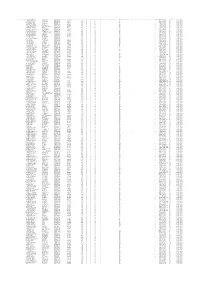

Voter Registration Number Name

VOTER REGISTRATION NUMBER NAME: LAST, FIRST, MIDDLE RESIDENTIAL ADDRESS: FULL STREET RESIDENTIAL ADDRESS: CITY/STATE/ZIP TELEPHONE: FULL NUMBER AGE AT YEAR END PARTY CODE RACE CODE GENDER CODE ETHNICITY CODE STATUS CODE JURISDICTION: MUNICIPAL DISTRICT CODE JURISDICTION: MUNICIPALITY CODE JURISDICTION: SANITATION DISTRICT CODE JURISDICTION: PRECINCT CODE REGISTRATION DATE VOTED METHOD VOTED PARTY CODE ELECTION NAME 141580 ACKISS, FRANCIS PAIGE 2 MULBERRY LN # A NEW BERN, NC 28562 252-671-5911 67 UNA W M NL A RIVE 5 2/25/2015 IN-PERSON UNA 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 140387 ADAMS, CHARLES RAYMOND 4100 HOLLY RIDGE RD NEW BERN, NC 28562 910-232-6063 74 DEM W M NL A TREN 3 10/10/2014 IN-PERSON DEM 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 20141 ADAMS, KAY RUSSELL 3605 BARONS WAY NEW BERN, NC 28562 252-633-2732 66 REP W F NL A TREN 3 5/24/1976 IN-PERSON REP 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 157173 ADAMS, LAUREN PAIGE 204 A ST BRIDGETON, NC 28519 252-474-9712 18 DEM W F NL A BRID FC 11 4/21/2017 IN-PERSON DEM 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 20146 ADAMS, LYNN EDWARD JR 3605 BARONS WAY NEW BERN, NC 28562 252-633-2732 69 REP W M NL A TREN 3 3/31/1970 IN-PERSON REP 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 66335 ADAMS, TRACY WHITFORD 204 A ST BRIDGETON, NC 28519 252-229-9712 47 REP W F NL A BRID FC 11 4/2/1998 IN-PERSON REP 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 49660 ADELSPERGER, ROBERT DEWEY 101 CHADWICK AVE HAVELOCK, NC 28532 252-447-0979 67 REP W M NL A HAVE 2 2/2/1994 IN-PERSON REP 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 71341 AGNEW, LYNNE ELIZABETH 31 EASTERN SHORE TOWNHOUSES BRIDGETON, NC 28519 252-638-8302 66 REP W F NL A BRID FC 11 7/27/1999 IN-PERSON -

Page 1 Halsbury's Laws of England (3) RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE

Page 1 Halsbury's Laws of England (3) RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE CROWN AND THE JUDICIARY 133. The monarch as the source of justice. The constitutional status of the judiciary is underpinned by its origins in the royal prerogative and its legal relationship with the Crown, dating from the medieval period when the prerogatives were exercised by the monarch personally. By virtue of the prerogative the monarch is the source and fountain of justice, and all jurisdiction is derived from her1. Hence, in legal contemplation, the Sovereign's Majesty is deemed always to be present in court2 and, by the terms of the coronation oath and by the maxims of the common law, as also by the ancient charters and statutes confirming the liberties of the subject, the monarch is bound to cause law and justice in mercy to be administered in all judgments3. This is, however, now a purely impersonal conception, for the monarch cannot personally execute any office relating to the administration of justice4 nor effect an arrest5. 1 Bac Abr, Prerogative, D1: see COURTS AND TRIBUNALS VOL 24 (2010) PARA 609. 2 1 Bl Com (14th Edn) 269. 3 As to the duty to cause law and justice to be executed see PARA 36 head (2). 4 2 Co Inst 187; 4 Co Inst 71; Prohibitions del Roy (1607) 12 Co Rep 63. James I is said to have endeavoured to revive the ancient practice of sitting in court, but was informed by the judges that he could not deliver an opinion: Prohibitions del Roy (1607) 12 Co Rep 63; see 3 Stephen's Commentaries (4th Edn) 357n. -

Conservative Party Strategy, 1997-2001: Nation and National Identity

Conservative Party Strategy, 1997-2001: Nation and National Identity A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy , Claire Elizabeth Harris Department of Politics, University of Sheffield September 2005 Acknowledgements There are so many people I'd like to thank for helping me through the roller-coaster experience of academic research and thesis submission. Firstly, without funding from the ESRC, this research would not have taken place. I'd like to say thank you to them for placing their faith in my research proposal. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Andrew Taylor. Without his good humour, sound advice and constant support and encouragement I would not have reached the point of completion. Having a supervisor who is always ready and willing to offer advice or just chat about the progression of the thesis is such a source of support. Thank you too, to Andrew Gamble, whose comments on the final draft proved invaluable. I'd also like to thank Pat Seyd, whose supervision in the first half of the research process ensured I continued to the second half, his advice, experience and support guided me through the challenges of research. I'd like to say thank you to all three of the above who made the change of supervisors as smooth as it could have been. I cannot easily put into words the huge effect Sarah Cooke had on my experience of academic research. From the beginnings of ESRC application to the final frantic submission process, Sarah was always there for me to pester for help and advice. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Daily Report Thursday, 14 January 2021 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 14 January 2021 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 14 January 2021 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:29 P.M., 14 January 2021). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 7 Police and Crime BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Commissioners: Elections 15 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 7 Schools: Procurement 16 Additional Restrictions Grant 7 Veterans: Suicide 16 Business: Coronavirus 7 DEFENCE 17 Business: Grants 8 Armed Forces: Health Conditions of Employment: Services 17 Re-employment 9 Defence: Expenditure 17 Industrial Health and Safety: HMS Montrose: Repairs and Coronavirus 9 Maintenance 18 Motor Neurone Disease: HMS Queen Elizabeth: Research 10 Repairs and Maintenance 18 Podiatry: Coronavirus 11 DIGITAL, CULTURE, MEDIA AND Public Houses: Coronavirus 11 SPORT 19 Wind Power 12 British Telecom: Disclosure of Information 19 CABINET OFFICE 13 Broadband: Elmet and Civil Servants: Business Rothwell 20 Interests 13 Broadband: Greater London 20 Coronavirus: Disease Control 13 Chatterley Whitfield Colliery 21 Coronavirus: Lung Diseases 13 Data Protection 22 Debts 14 Educational Broadcasting: Fisheries: UK Relations with Coronavirus 23 EU 14 Events Industry and Iron and Steel: Procurement 14 Performing Arts: Greater National Security Council: London 23 Coronavirus 15 Football: Dementia 24 Football: Gambling 24 Organic Food: UK Trade with Freedom of Expression -

Conservative Party Leaders and Officials Since 1975

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07154, 6 February 2020 Conservative Party and Compiled by officials since 1975 Sarah Dobson This List notes Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975. Further reading Conservative Party website Conservative Party structure and organisation [pdf] Constitution of the Conservative Party: includes leadership election rules and procedures for selecting candidates. Oliver Letwin, Hearts and Minds: The Battle for the Conservative Party from Thatcher to the Present, Biteback, 2017 Tim Bale, The Conservative Party: From Thatcher to Cameron, Polity Press, 2016 Robert Blake, The Conservative Party from Peel to Major, Faber & Faber, 2011 Leadership elections The Commons Library briefing Leadership Elections: Conservative Party, 11 July 2016, looks at the current and previous rules for the election of the leader of the Conservative Party. Current state of the parties The current composition of the House of Commons and links to the websites of all the parties represented in the Commons can be found on the Parliament website: current state of the parties. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975 Leader start end Margaret Thatcher Feb 1975 Nov 1990 John Major Nov 1990 Jun 1997 William Hague Jun 1997 Sep 2001 Iain Duncan Smith Sep 2001 Nov 2003 Michael Howard Nov 2003 Dec 2005 David Cameron Dec 2005 Jul 2016 Theresa May Jul 2016 Jun 2019 Boris Johnson Jul 2019 present Deputy Leader # start end William Whitelaw Feb 1975 Aug 1991 Peter Lilley Jun 1998 Jun 1999 Michael Ancram Sep 2001 Dec 2005 George Osborne * Dec 2005 July 2016 William Hague * Dec 2009 May 2015 # There has not always been a deputy leader and it is often an official title of a senior Conservative politician. -

Open Government Plan

United States Department of State Open Government Plan September 2016 OPEN GOVERNMENT PLAN U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 4 New and Expanded Initiatives ................................................................................................................ 6 Open Data ................................................................................................................................... 6 Proactive Disclosures .................................................................................................................. 9 Privacy ...................................................................................................................................... 10 Whistleblower Protection...........................................................................................................11 Websites .................................................................................................................................... 12 Open Innovation Methods......................................................................................................... 13 Access to Scientific Data and Publications ............................................................................... 14 Open Source