Arab Media Systems EDITED by CAROLA RICHTER and CLAUDIA KOZMAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The British Resident in Transjordan and the Financial Administration in the Emirate Transjordan 1921-1928

Journal of Politics and Law; Vol. 5, No. 4; 2012 ISSN 1913-9047 E-ISSN 1913-9055 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The British Resident in Transjordan and the Financial Administration in the Emirate Transjordan 1921-1928 Riyadh Mofleh Klaifat1 1 Department of Basic Sciences, AL-Huson University College, Al Balqa’ Applied University, Irbid, Jordan Correspondence: Riyadh Mofleh Klaifat, Department of Basic Sciences, AL-Huson University College, Al Balqa’ Applied University, P.O. Box 50, Al-Huson 21510, Irbid, Jordan. Tel: 96-277-724-7370. E-mail: [email protected] Received: July 1, 2012 Accepted: July 9, 2012 Online Published: November 29, 2012 doi:10.5539/jpl.v5n4p159 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v5n4p159 Abstract Transjordan as a part of Belad Esham was subject to the Ottoman authority dominated the area from 1516 G up to the Call of Sherif Mecca (Al Hussain Bin Ali) for the revolution on the Ottoman Authority in 1916 after being promised false promises many times, such as the promise given to Sherif Hussain for replacing the Turkish rule by the Arab rule, during that period Britain was making conspiracies with the big Greedy powers in the area through bilateral negotiation with France ended by signing a new treaty called Sykes-Picot Treaty where the Arab map was divided between the two Countries. Where Arabs found themselves after the 1st world war after the defeat of Turkish state in 1918 G became under the rule of a news colonial powers, under what called the mandatory system which was established by the colonial powers to achieve their economic and social ambitions. -

ORIGINS of the PALESTINE MANDATE by Adam Garfinkle

NOVEMBER 2014 ORIGINS OF THE PALESTINE MANDATE By Adam Garfinkle Adam Garfinkle, Editor of The American Interest Magazine, served as the principal speechwriter to Secretary of State Colin Powell. He has also been editor of The National Interest and has taught at Johns Hopkins University’s School for Advanced International Studies (SAIS), the University of Pennsylvania, Haverford College and other institutions of higher learning. An alumnus of FPRI, he currently serves on FPRI’s Board of Advisors. This essay is based on a lecture he delivered to FPRI’s Butcher History Institute on “Teaching about Israel and Palestine,” October 25-26, 2014. A link to the the videofiles of each lecture can be found here: http://www.fpri.org/events/2014/10/teaching-about- israel-and-palestine Like everything else historical, the Palestine Mandate has a history with a chronological beginning, a middle, and, in this case, an end. From a strictly legal point of view, that beginning was September 29, 1923, and the end was midnight, May 14, 1948, putting the middle expanse at just short of 25 years. But also like everything else historical, it is no simple matter to determine either how far back in the historical tapestry to go in search of origins, or how far to lean history into its consequences up to and speculatively beyond the present time. These decisions depend ultimately on the purposes of an historical inquiry and, whatever historical investigators may say, all such inquiries do have purposes, whether recognized, admitted, and articulated or not. A.J.P. Taylor’s famous insistence that historical analysis has no purpose other than enlightened storytelling, rendering the entire enterprise much closer to literature than to social science, is interesting precisely because it is such an outlier perspective among professional historians. -

Morocco: an Emerging Economic Force

Morocco: An Emerging Economic Force The kingdom is rapidly developing as a manufacturing export base, renewable energy hotspot and regional business hub OPPORTUNITIES SERIES NO.3 | DECEMBER 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY 3 I. ECONOMIC FORECAST 4-10 1. An investment and export-led growth model 5-6 2. Industrial blueprint targets modernisation. 6-7 3. Reforms seek to attract foreign investment 7-9 3.1 Improvements to the business environment 8 3.2 Specific incentives 8 3.3 Infrastructure improvements 9 4. Limits to attractiveness 10 II. SECTOR OPPORTUNITIES 11-19 1. Export-orientated manufacturing 13-15 1.1 Established and emerging high-value-added industries 14 2. Renewable energy 15-16 3. Tourism 16-18 4. Logistics services 18-19 III. FOREIGN ECONOMIC RELATIONS 20-25 1. Africa strategy 20-23 1.1 Greater export opportunities on the continent 21 1.2 Securing raw material supplies 21-22 1.3 Facilitating trade between Africa and the rest of the world 22 1.4 Keeping Africa opportunities in perspective 22-23 2. China ties deepening 23-24 2.1 Potential influx of Chinese firms 23-24 2.2 Moroccan infrastructure to benefit 24 3 Qatar helping to mitigate reduction in gulf investment 24-25 IV. KEY RISKS 26-29 1. Social unrest and protest 26-28 1.1 2020 elections and risk of upsurge in protest 27-28 1.2 But risks should remain contained 28 2. Other important risks 29 2.1 Export demand disappoints 29 2.2 Exposure to bad loans in SSA 29 2.3 Upsurge in terrorism 29 SUMMARY Morocco will be a bright spot for investment in the MENA region over the next five years. -

Tout Ce Que Vous Devez Savoir Condor À L’Heure Du Cristal

Le satellite ALSAT 2B Médias Mobiles lancé début 2016 Mensuel de la Télévision, du Satellite et des Télécoms 4K & ULTRA HD Tout ce que vous devez savoir Condor à l’heure du Cristal UN PETIT RÉCEPTEUR AUX DENTS LONGUES ATLASHD-200s Allure A9+ Idol 3 le plus le fer de lance de Condor d’Alcatel 3 Questions à... Hamid Grine Numéro : 01 du 15 Novembre 2015 au 15 Décembre 2015 Prix : 170 DA Sommaire Média & Mobile 5 Edito Numéro 01 Du 15 Novembre au 15 Décembre 2015 6 Questions à... Mensuel dédié aux satellites, nouvelles technologies de la communication, médias audiovisuels et à la téléphonie - M.Hamid Grine, Ministre de la Communication Siège rédactionnel : 1, rue Abdelkrim El Khattabi, Grande Poste, Alger Téléphone : 021 632 729 7 Actuelles GSM : 0 557 294 158 Mail : [email protected] RC : 15B0366181-23/00 - Chaines locales Compte bancaire : 004 00201 400 00 27 377 46 - ALSAT 2B lancée début 2016 DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION - Le nouveau satellite Eutelsat 8B opérationnel Maâmar FARAH : [email protected] - Les nouvelles positions des chaines algérienne - KBC veut élargir ces émissions en tamazight DIRECTEUR DE LA RÉDACTION : - Condor lance le plume P4 Benkheira Nacer : [email protected] RÉDACTION : 14 Techno-futur Mourad Nini : [email protected] Samir Rabah : [email protected] Nesma Aghiles : [email protected] - Li-Fi: l'Internet haut débit par la lumière Ben Mohamed .G [email protected] Hakim Laâlam : [email protected] - Un Samsung avec un écran pliable CONFECTION ET INFOGRAPHIE: Karim Mostefai : [email protected] Chronique SERVICE COMMERCIAL : 15 Lilia TALBI: [email protected] - Fréquences en transes VENTE ET DIFFUSION : Mohamed Walid FARAH : [email protected] IMPRIMERIE : Market-Sat Eurl kim : (Karim imprimerie moderne). -

As It Sides with Qatar, Turkey Tries to Pre-Empt Own Isolation

Roufan Nahhas, Rashmee Roshan Lall, Iman Zayat, Gareth Smyth, Jareer Elass, Stephen Quillen, Mamoon Alabbasi , Yavuz Baydar, Rami Rayess Issue 111, Year 3 www.thearabweekly.com UK £2/ EU €2.50 June 18, 2017 The Middle Saif al-Islam’s East’s smoking release and the problem future of Libya P4 P22 P10 Facing radical Islam P18 As it sides with Qatar, Turkey tries to pre-empt own isolation Mohammed Alkhereiji Saud — “the elder statesman of the 150 additional Turkish troops in Gulf” — should resolve the matter. Doha. There was also a pledge by He needed to maintain a margin of members of the Qatari royal family London manoeuvre to keep his meditation for more investments in Turkey. posture and forestall the risk of An- Galip Dalay, research director at Al s it makes statements kara’s own isolation. Sharq Forum, a Turkish research or- that give the impression Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut ganisation, told the New York Times of a position of mediation Cavusoglu, who met with King Sal- that Turkey was “transitioning from in the Gulf crisis, Turkey man in Mecca on June 16, spoke in neutral mediator to the role of firm- is working to make sure it similarly vague terms. ly supporting the side of Qatar” by isA not the next Muslim Brotherhood- “Although the kingdom is a party voting to send troops to Qatar. affiliated country to face regional in this crisis, we know that King Sal- The Turkish position was in line isolation. man is a party in resolving it,” Cavu- with Ankara’s common affinities A lot has happened since 2015 soglu said at a Doha stopover prior with Doha as another country fac- when Turkish President Recep to his Mecca meeting. -

"The Yacoubian Building" by Alaa Al Aswany, Part 1 Reading in Retirement by Dr

"The Yacoubian Building" by Alaa Al Aswany, Part 1 Reading in Retirement by Dr. Charles S. Grippi This is the first of a three part series. Aswany's "The Yacoubian Building" (Arabic version 2002 and the English translation by Humphrey Davies, New York: Harper Perennial Ed., 2006) is a quite cogent novel in a number of ways. Centered in Cairo, Egypt, the cultural capital of the Muslim world, in the early 1990's, the novel reveals an expansively liberating spirit on subjects that were strictly taboo for publication in a Muslim country and certainly are still anathema in fundamentalist countries of the Muslim world. The novel took Egypt by storm by becoming a best seller in 2002 and 2003 and then being proclaimed the best novel in 2003. To date, the novel has been translated into 23 languages. Made into an "Adults Only" film in 2006, it broke a box office attendance record by earning 6,000,000 Egyptian Pounds the first week and 20,000,000 E.Ps. during its initial theatrical run. In 2006, the film was submitted as Egypt's entry to the 79th Academy Awards "Best Foreign Film Category." In 2006, a television series bearing the same name began: however, frank sexual scenes were omitted. The novel created political controversy by its attacks on the corrupt, undemocratic one party system that has ruled since the country gained its independence with the overthrow of the puppet government of King Farouk that was supported by the British. The revolution allowed Egyptians to rule their own country for the first time in almost 2,500 years harking back to the invasions of the Persians and by the Greek Alexander the Great in the 4th century B.C. -

S O N a S I D R a P P O R T a N N U

SONASID Rapport Annuel 2 0 1 0 [Rapport Annuel 2010] { S ommaire} 04 MESSAGE DU DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL 06 HISTORIQUE 07 PROFIL 09 CARNET DE L’ACTIONNAIRE 10 GOUVERNANCE 15 STRATÉGIE 19 ACTIVITÉ 25 RAPPORT SOCIAL 31 ÉLÉMENTS FINANCIERS 3 [Rapport Annuel 2010] Chers actionnaires, L’année 2010 a été particulièrement difficile pour l’ensemble Sonasid devrait en effet profiter d’un marché international des entreprises sidérurgiques au Maroc qui ont subi de favorable qui augure de bonnes perspectives avec la plein fouet à la fois les fluctuations d’un marché international prudence nécessaire, eu égard des événements récents Message du perturbé et la baisse locale des mises en chantier dans imprévisibles (Japon, monde arabe), mais une tendance { l’immobilier et le BTP. Une situation qui a entraîné une qui se confirme également sur le marché local qui devrait réduction de la consommation nationale du rond-à-béton bénéficier dès le second semestre 2011 de la relance des Directeur General qui est passée de 1500 kt en 2009 à 1400 kt en 2010. chantiers d’infrastructures et d’habitat social. } Un recul aggravé par la hausse des prix des matières premières, la ferraille notamment qui a représenté 70% du Nous sommes donc optimistes pour 2011 et mettrons prix de revient du rond-à-béton. Les grands consommateurs en œuvre toutes les mesures nécessaires pour y parvenir. d’acier sont responsables de cette inflation, la Chine en Nous avons déjà en 2010 effectué des progrès notables au particulier, au détriment de notre marché qui, mondialisé, a niveau de nos coûts de transformations, efforts que nous été directement affecté. -

Liste Des Chaines

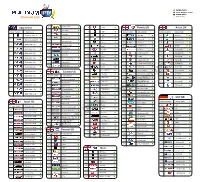

Available channel temporary unabled channel disabled channel Channels List channel replay Setanta Sport 46 92 Gold Family UK Asian UK 47 Box Nation channel number channel name 93 Dave channel number channel name channel number channel name 48 ESPN HD 1 beIN Sports News HD 94 Alibi 104 SKY ONE 158 Zee tv UK 49 Eurosport UK 95 E4 105 Sky Two UK 159 Zee cinema UK 2 Bein Sports Global HD 50 Eurosport 2 UK 96 More 4 106 Sky Living 160 Zee Punjabi UK 3 BEIN SPORT 1 HD 51 Sky Sports News 97 Dmax 107 Sky Atlantic UK 161 Zing UK 52 At The Races 4 BEIN SPORT 2 HD 98 5 STAR 108 Sky Arts1 162 Star Gold UK 53 Racing UK 5 BEIN SPORT 3 HD 99 3E 109 Sky Real Lives UK 163 Star Jalsha UK 54 Motor TV 100 Magic 110 Fox UK 164 Star Plus UK 6 BEIN SPORT 4 HD 55 Manchester United Tv 101 TV 3 111 Comedy Central UK 165 Star live UK 7 BEIN SPORT 5 HD 56 Chealsea Tv 102 Film 4 121 Comedy Central Extra UK 166 Ary Digital UK 57 Liverpool Tv 8 BEIN SPORT 6 HD 103 Flava 125 Nat Geo UK 167 Sony Tv UK 113 Food Network 126 Nat Geo Wild uk 168 Sony Sab Tv UK 9 BEIN SPORT 7 HD Cinema Uk 114 The Vault 127 Discovery UK 169 Aaj Tak UK 10 BEIN SPORT 8 HD channel number channel name 115 CBS Reality 128 Discovery Science uk 170 Geo TV UK 60 Sky Movies Premiere UK 11 BEIN SPORT 9 HD 116 CBS Action 129 Discovery Turbo UK 171 Geo news UK 61 Sky Select UK 12 BEIN SPORT 10 HD 130 Discovery History 172 ABP news Uk 62 Sky Action UK 117 CBS Drama 131 Discovery home UK 13 BEIN SPORT 11 HD 63 Sky Modern Great UK 118 True Movies 132 Investigation Discovery 64 Sky Family UK 119 True Movies -

Islam, Democracy, and Governance: Sudan and Morocco in a Comparative Perspective

ISLAM, DEMOCRACY, AND GOVERNANCE: SUDAN AND MOROCCO IN A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE By WALEED MOUSA A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2005 Copyright 2005 by Waleed Mousa There is not a single night in which I do put my head over the pillow without thinking of the poor in my nation and in the world in large. It is to those impoverished people, to my parents who helped me reach this level of conscientiousness, to my wife whose love helped me overcome the agony, and to my children whose heavenly spirit helped sustain my soul that I dedicate this dissertation. Waleed Madibbo TABLE OF CONTENTS page LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... vi ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................... vii CHAPTER 1 AN OVERVIEW..........................................................................................................1 2 ISLAM AND DEMOCRACY....................................................................................12 Political Authority in Islam Prior to Modernity .........................................................14 Modernization and Colonialism: The Creation of “the Other” ..................................23 Islamic Revivalism: Adaptation or Retreat.................................................................34 Modernity -

Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps

Morocco/Western Sahara/Algeria HUMAN Human Rights in Western Sahara RIGHTS and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps WATCH Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Morocco/Western Sahara/Algeria Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-420-6 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org December 2008 1-56432-420-6 Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Map Of North Africa ....................................................................................................... 1 Summary...................................................................................................................... 2 Western Sahara ....................................................................................................... 3 Refugee Camps near Tindouf, Algeria ...................................................................... 8 Recommendations ...................................................................................................... 12 To the UN Security Council .................................................................................... -

LES CHAÎNES TV by Dans Votre Offre Box Très Haut Débit Ou Box 4K De SFR

LES CHAÎNES TV BY Dans votre offre box Très Haut Débit ou box 4K de SFR TNT NATIONALE INFORMATION MUSIQUE EN LANGUE FRANÇAISE NOTRE SÉLÉCTION POUR VOUS TÉLÉ-ACHAT SPORT INFORMATION INTERNATIONALE MULTIPLEX SPORT & ÉCONOMIQUE EN VF CINÉMA ADULTE SÉRIES ET DIVERTISSEMENT DÉCOUVERTE & STYLE DE VIE RÉGIONALES ET LOCALES SERVICE JEUNESSE INFORMATION INTERNATIONALE CHAÎNES GÉNÉRALISTES NOUVELLE GÉNÉRATION MONDE 0 Mosaïque 34 SFR Sport 3 73 TV Breizh 1 TF1 35 SFR Sport 4K 74 TV5 Monde 2 France 2 36 SFR Sport 5 89 Canal info 3 France 3 37 BFM Sport 95 BFM TV 4 Canal+ en clair 38 BFM Paris 96 BFM Sport 5 France 5 39 Discovery Channel 97 BFM Business 6 M6 40 Discovery Science 98 BFM Paris 7 Arte 42 Discovery ID 99 CNews 8 C8 43 My Cuisine 100 LCI 9 W9 46 BFM Business 101 Franceinfo: 10 TMC 47 Euronews 102 LCP-AN 11 NT1 48 France 24 103 LCP- AN 24/24 12 NRJ12 49 i24 News 104 Public Senat 24/24 13 LCP-AN 50 13ème RUE 105 La chaîne météo 14 France 4 51 Syfy 110 SFR Sport 1 15 BFM TV 52 E! Entertainment 111 SFR Sport 2 16 CNews 53 Discovery ID 112 SFR Sport 3 17 CStar 55 My Cuisine 113 SFR Sport 4K 18 Gulli 56 MTV 114 SFR Sport 5 19 France Ô 57 MCM 115 beIN SPORTS 1 20 HD1 58 AB 1 116 beIN SPORTS 2 21 La chaîne L’Équipe 59 Série Club 117 beIN SPORTS 3 22 6ter 60 Game One 118 Canal+ Sport 23 Numéro 23 61 Game One +1 119 Equidia Live 24 RMC Découverte 62 Vivolta 120 Equidia Life 25 Chérie 25 63 J-One 121 OM TV 26 LCI 64 BET 122 OL TV 27 Franceinfo: 66 Netflix 123 Girondins TV 31 Altice Studio 70 Paris Première 124 Motorsport TV 32 SFR Sport 1 71 Téva 125 AB Moteurs 33 SFR Sport 2 72 RTL 9 126 Golf Channel 127 La chaîne L’Équipe 190 Luxe TV 264 TRACE TOCA 129 BFM Sport 191 Fashion TV 265 TRACE TROPICAL 130 Trace Sport Stars 192 Men’s Up 266 TRACE GOSPEL 139 Barker SFR Play VOD illim. -

Public Broadcasting in North Africa and the Middle East

Published by Panos Paris Institute and Mediterranean Observatory of Communication © Consortium IPP-OMEC Date of publication May 2012 ISBN 978-84-939674-0-6 Panos Paris Institute 10, rue du Mail - F-75002 Paris Phone: +33 (0)1 40 41 13 31 Fax: 33 (0)1 40 41 03 30 http://www.panosparis.org Observatori Mediterrani de la Comunicació Campus de la UAB 08193 Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallès) Phone: (+34) 93 581 3160 http://omec.uab.cat/ Responsibility for the content of these publications rests fully with their authors, and their publication does not constitute an endorsement by the Generalitat, Irish Aid nor the Open Society Foundations of the opinions expressed. Catalan publication: Editing: Annia García Printing: Printcolor, s.l French, English, Arabic publications: Editing: Caractères Pre-Press Printing: XL Print Photo Credits Front Cover: istockphoto.com Team responsible for the regional report This book owes much to the teams of the Panos Paris Institute (IPP), the Mediterranean Observatory of Communication (OMEC) and to the project partners in the countries of the MENA region: the Algerian League for the Defence of Human Rights (LADDH Algeria), the Community Media Network (CMN, Jordan), Maharat foundation (Lebanon), the Centre for Media Freedom Middle East North Africa (CMF MENA, Morocco) and the AMIN Media Network (Palestine). Coordination of the regional report Charles AUTHEMAN (IPP) Coordinator Olga DEL RIO (OMEC) Coordinator Latifa TAYAH-GUENEAU (IPP) Coordinator Editorial committee Ricardo CARNIEL BUGS (OMEC) Editor Roland HUGUENIN-BENJAMIN (associate expert IPP) Editor Authors of the national reports Algeria Belkacem MOSTAFAOUI Professor, National Superior School of journalism and information sciences, Algiers Abdelmoumène KHELIL General Secretary, LADDH Egypt Rasha A.