“Tips for Tonguing” by Howard Klug

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Dynamic Markings

Basic Dynamic Markings • ppp pianississimo "very, very soft" • pp pianissimo "very soft" • p piano "soft" • mp mezzo-piano "moderately soft" • mf mezzo-forte "moderately loud" • f forte "loud" • ff fortissimo "very loud" • fff fortississimo "very, very loud" • sfz sforzando “fierce accent” • < crescendo “becoming louder” • > diminuendo “becoming softer” Basic Anticipation Markings Staccato This indicates the musician should play the note shorter than notated, usually half the value, the rest of the metric value is then silent. Staccato marks may appear on notes of any value, shortening their performed duration without speeding the music itself. Spiccato Indicates a longer silence after the note (as described above), making the note very short. Usually applied to quarter notes or shorter. (In the past, this marking’s meaning was more ambiguous: it sometimes was used interchangeably with staccato, and sometimes indicated an accent and not staccato. These usages are now almost defunct, but still appear in some scores.) In string instruments this indicates a bowing technique in which the bow bounces lightly upon the string. Accent Play the note louder, or with a harder attack than surrounding unaccented notes. May appear on notes of any duration. Tenuto This symbol indicates play the note at its full value, or slightly longer. It can also indicate a slight dynamic emphasis or be combined with a staccato dot to indicate a slight detachment. Marcato Play the note somewhat louder or more forcefully than a note with a regular accent mark (open horizontal wedge). In organ notation, this means play a pedal note with the toe. Above the note, use the right foot; below the note, use the left foot. -

Articulation from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Articulation From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Examples of Articulations: staccato, staccatissimo,martellato, marcato, tenuto. In music, articulation refers to the musical performance technique that affects the transition or continuity on a single note, or between multiple notes or sounds. Types of articulations There are many types of articulation, each with a different effect on how the note is played. In music notation articulation marks include the slur, phrase mark, staccato, staccatissimo, accent, sforzando, rinforzando, and legato. A different symbol, placed above or below the note (depending on its position on the staff), represents each articulation. Tenuto Hold the note in question its full length (or longer, with slight rubato), or play the note slightly louder. Marcato Indicates a short note, long chord, or medium passage to be played louder or more forcefully than surrounding music. Staccato Signifies a note of shortened duration Legato Indicates musical notes are to be played or sung smoothly and connected. Martelato Hammered or strongly marked Compound articulations[edit] Occasionally, articulations can be combined to create stylistically or technically correct sounds. For example, when staccato marks are combined with a slur, the result is portato, also known as articulated legato. Tenuto markings under a slur are called (for bowed strings) hook bows. This name is also less commonly applied to staccato or martellato (martelé) markings. Apagados (from the Spanish verb apagar, "to mute") refers to notes that are played dampened or "muted," without sustain. The term is written above or below the notes with a dotted or dashed line drawn to the end of the group of notes that are to be played dampened. -

Composers' Bridge!

Composers’ Bridge Workbook Contents Notation Orchestration Graphic notation 4 Orchestral families 43 My graphic notation 8 Winds 45 Clefs 9 Brass 50 Percussion 53 Note lengths Strings 54 Musical equations 10 String instrument special techniques 59 Rhythm Voice: text setting 61 My rhythm 12 Voice: timbre 67 Rhythmic dictation 13 Tips for writing for voice 68 Record a rhythm and notate it 15 Ideas for instruments 70 Rhythm salad 16 Discovering instruments Rhythm fun 17 from around the world 71 Pitch Articulation and dynamics Pitch-shape game 19 Articulation 72 Name the pitches – part one 20 Dynamics 73 Name the pitches – part two 21 Score reading Accidentals Muddling through your music 74 Piano key activity 22 Accidental practice 24 Making scores and parts Enharmonics 25 The score 78 Parts 78 Intervals Common notational errors Fantasy intervals 26 and how to catch them 79 Natural half steps 27 Program notes 80 Interval number 28 Score template 82 Interval quality 29 Interval quality identification 30 Form Interval quality practice 32 Form analysis 84 Melody Rehearsal and concert My melody 33 Presenting your music in front Emotion melodies 34 of an audience 85 Listening to melodies 36 Working with performers 87 Variation and development Using the computer Things you can do with a Computer notation: Noteflight 89 musical idea 37 Sound exploration Harmony My favorite sounds 92 Harmony basics 39 Music in words and sentences 93 Ear fantasy 40 Word painting 95 Found sound improvisation 96 Counterpoint Found sound composition 97 This way and that 41 Listening journal 98 Chord game 42 Glossary 99 Welcome Dear Student and family Welcome to the Composers' Bridge! The fact that you are being given this book means that we already value you as a composer and a creative artist-in-training. -

Slap Tongue (Saxophone Pizzicato)

Excerpt from “Part IV: Extended Techniques for Saxophone” Writing for Saxophones: A Guide to the Tonal Palette of the Saxophone Family for Composers, Arrangers and Performers by Jay C. Easton, D.M.A. (for further excerpts and ordering information, please visit http://baxtermusicpublishing.com) • Slap Tongue (saxophone pizzicato) Slap tongue is a versatile and interesting effect that is available in four varieties: 1. “melodic” slap or pizzicato (clearly pitched): melodic “plucking” sound entire keyed range of horn (but not altissimo) Maximum tempo: 240 beats per minute Possible from p to f dynamics 2. “slap tone” (clearly pitched): melodic slap attack followed by normal tone Maximum tempo: 200 beats per minute Possible from p to f dynamics 3. “woodblock” slap (unpitched): soft, dry percussive sound Maximum tempo: 200 beats per minute Possible from p to mf dynamics 4. “explosive” slap or “open” slap (unpitched): loud percussive sound Maximum tempo: 70 beats per minute Possible from mf to ff dynamics Not all saxophonists know how to slap tongue but an increasing number are learning the technique. The “melodic” slap and “slap tone” are produced by holding the tongue against about 1/3 to 1/2 of the tip end of the reed surface – a centimeter or so – and creating a suction-cup effect between tongue and reed. This is accomplished by pulling the middle of the tongue slightly away from the reed while keeping the edges and tip of the tongue sealed tight against it. The tongue is then quickly released by pushing it forward and downward away from the reed, creating suction between the tongue and the reed; this tongue motion is accompanied by sudden slight impulse of air. -

Music Is Made up of Many Different Things Called Elements. They Are the “I Feel Like My Kind Building Bricks of Music

SECONDARY/KEY STAGE 3 MUSIC – BUILDING BRICKS 5 MINUTES READING #1 Music is made up of many different things called elements. They are the “I feel like my kind building bricks of music. When you compose a piece of music, you use the of music is a big pot elements of music to build it, just like a builder uses bricks to build a house. If of different spices. the piece of music is to sound right, then you have to use the elements of It’s a soup with all kinds of ingredients music correctly. in it.” - Abigail Washburn What are the Elements of Music? PITCH means the highness or lowness of the sound. Some pieces need high sounds and some need low, deep sounds. Some have sounds that are in the middle. Most pieces use a mixture of pitches. TEMPO means the fastness or slowness of the music. Sometimes this is called the speed or pace of the music. A piece might be at a moderate tempo, or even change its tempo part-way through. DYNAMICS means the loudness or softness of the music. Sometimes this is called the volume. Music often changes volume gradually, and goes from loud to soft or soft to loud. Questions to think about: 1. Think about your DURATION means the length of each sound. Some sounds or notes are long, favourite piece of some are short. Sometimes composers combine long sounds with short music – it could be a song or a piece of sounds to get a good effect. instrumental music. How have the TEXTURE – if all the instruments are playing at once, the texture is thick. -

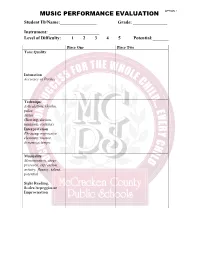

Music Performance Evaluation

OPTION 1 Student ID/Name:________________ Grade: _______________ Instrument: ______________________ Level of Difficulty: 1 2 3 4 5 Potential:_______ Piece One Piece Two Tone Quality Intonation Accuracy of Pitches Technique Articulation, rhythm, pulse, Meter (Bowing, diction, tonguing, sticking) Interpretation Phrasing, expressive elements, nuance, dynamics, tempo Musicality Memorization, stage presence, expression, artistry, fluency, talent, potential Sight Reading, Scales/Arpeggios or Improvisation OPTION 1 Distinguished Proficient Apprentice Novice Tone Quality Tone is warm, resonant, Tone has some Tone has apparent Tone is weak, controlled, clear, focused, warmth, resonance inconsistencies breathy, forced consistent, vibrant, rich, and clarity, with with some or unclear. full, beautiful. some resonance and inconsistencies. clarity. Intonation Printed pitches are Some inaccurate Several inaccurate Inaccurate Accuracy of performed with accuracy; pitches and some pitches and pitches; out of intonation is within the intonation problems. difficulty tune. Pitches appropriate range. Student playing/singing in shifts cleanly. tune consistently. Technique Student used appropriate Enough technical Some technical Flawed Articulation, technique, as printed or flaws to detract from flaws. Not technique. indicated stylistically for performance. Style stylistically Inaccurate rhythm, pulse, the selection. Attacks and somewhat appropriate. rhythms, time Meter releases are clear. Slurs appropriate. Some Printed signature not (Bowing, diction, are smooth and connected. inconsistencies in articulations not followed, tonguing, Pulse of the music is performance or followed accents sticking, steady. Indicated meter is printed articulations. accurately. overdone or not performed correctly. Some unsteadiness Unsteady pulse. apparent. Slurs fingering) Notes and rests are held for of pulse. Some Several rhythmic are unclear. the correct value. rhythmic errors. errors. Technique is not appropriate stylistically. -

Download File

NAVIGATING MUSICAL PERIODICITIES: MODES OF PERCEPTION AND TYPES OF TEMPORAL KNOWLEDGE Galen Philip DeGraf Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Galen Philip DeGraf All rights reserved ABSTRACT Navigating Musical Periodicities: Modes of Perception and Types of Temporal Knowledge Galen Philip DeGraf This dissertation explores multi-modal, symbolic, and embodied strategies for navigating musical periodicity, or “meter.” In the first half, I argue that these resources and techniques are often marginalized or sidelined in music theory and psychology on the basis of definition or context, regardless of usefulness. In the second half, I explore how expanded notions of metric experience can enrich musical analysis. I then relate them to existing approaches in music pedagogy. Music theory and music psychology commonly assume experience to be perceptual, music to be a sound object, and perception of music to mean listening. In addition, observable actions of a metaphorical “body” (and, similarly, performers’ perspectives) are often subordinate to internal processes of a metaphorical “mind” (and listeners’ experiences). These general preferences, priorities, and contextual norms have culminated in a model of “attentional entrainment” for meter perception, emerging through work by Mari Riess Jones, Robert Gjerdingen, and Justin London, and drawing upon laboratory experiments in which listeners interact with a novel sound stimulus. I hold that this starting point reflects a desire to focus upon essential and universal aspects of experience, at the expense of other useful resources and strategies (e.g. extensive practice with a particular piece, abstract ideas of what will occur, symbolic cues) Opening discussion of musical periodicity without these restrictions acknowledges experiences beyond attending, beyond listening, and perhaps beyond perceiving. -

The Influence of Tonguing on Tone Production With

5th Congress of Alps-Adria Acoustics Association 12-14 September 2012, Petrþane, Croatia __________________________________________________________________________________________ !"#$% #' !($!(#) "#)!(#!(# !*+(, '"(#!-"! ."#)% /+ ,!-((,-"#,!"#.+ 0 #. Alex Hofmann,*¹ Vasileios Chatziioannou,* Wilfried Kausel,* Werner Goebl,* Michael Weilguni,# Walter Smetana # *Institute of Music Acoustics, University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, Austria #Institute of Sensor and Actuator Systems, Vienna University of Technology, Austria ¹[email protected] Abstract: Physical modelling based sound-synthesis requires physically meaningful parameters for controlling the model. Previous studies on modelling single-reed woodwind instruments have concentrated mostly on the influence of the pressure difference across the reed on the behavior of the reed oscillation. The interaction with the player's lips and the mouthpiece lay has also been taken into account. However, studies on the effect of the player's tongue are limited. Articulation on real saxophones is produced by tongue impulses to the reed. In portato playing the air pressure is held approximately constant by the player, while there are articular interactions of the tongue with the reed. In this study we aim to explain the influence of tonguing for tone production with single-reed woodwind instruments using experimental measurements in an attempt to model articulation in sound synthesis. During the experiments an alto-saxophone mouthpiece was attached to the saxophone neck and tones with different articulation were recorded. The mouthpiece pressure was measured using a microphone inserted into the mouthpiece and a strain gauge glued on a synthetic reed was used to track the reed bending. A damping effect of the tongue on the oscillating reed can be observed between two articulated tones and the release of the tongue affects the transient behavior of the instrument. -

Choir 6 Grade

Choir 6th Grade Jessica Arnold, Northwest Middle School Vicki Mount, North Middle School Amy Smick, East/Southeast Middle School Matt McClellan – Special Areas Curriculum Coordinator Reviewed by Curriculum Advisory Committee on October 9, 2014 Presented to the Board of Education on December 16, 2014 COURSE TITLE: Choir 6 GRADE LEVEL: 6th CONTENT AREA: Fine Arts Course Description: Students will study vocal techniques, ensemble skills, and basic music theory as related to appropriate music level. Performances are mandatory at the discretion of the teacher. Course Rationale: 6th Grade Choir serves as an introduction to vocal music. Students will develop basic vocal techniques while incorporating the higher order thinking skills of analysis, synthesis, and evaluation in order to have a meaningful musical experience. Course Scope and Sequence Unit 1: Rehearsal and Unit 2: Rhythm Notation and Unit 3: Pitch Notation and Performance Technique Reading Reading (ongoing) (12 weeks) (12 weeks) Unit 4: Road Maps of Unit 5: Dynamics Music/Signs and Symbols (4 weeks) (4 weeks) Unit Objectives: Unit 1: Rehearsals and Performance Technique 1. Students will know the importance of warming up prior to singing. 2. Students will apply techniques to create a quality singing tone. 3. Students will apply the concept of balance and blend across a choral ensemble. 4. Students will sing 2‐part music in the choral setting. 5. Students will sing using the appropriate expression for the context of the selected piece. 6. Students will display appropriate concert etiquette on stage and in the audience. Unit 2: Rhythm Notation and Reading 1. Students will know basic vocabulary regarding rhythmic notation, including staff, time signature, barline, measure, and double barline. -

Extended Techniques in Stanley Friedman's

EXTENDED TECHNIQUES IN STANLEY FRIEDMAN'S SOLUS FOR UNACCOMPANIED TRUMPET Scott Meredith, B.M., B.M.E., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2008 APPROVED: Keith Johnson, Major Professor Lenora McCroskey, Minor Professor John Holt, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Meredith, Scott. Extended Techniques in Stanley Friedman’s Solus for Unaccompanied Trumpet. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2008, 37 pp., 25 examples, 3 tables, bibliography, 23 titles. This document examines the technical execution of extended techniques incorporated in the musical structure of Solus, and explores the benefits of introducing the work into the curriculum of a college level trumpet studio. Compositional style, form, technical accessibility, and pedagogical benefits are investigated in each of the four movements. An interview with the composer forms the foundation for the history of the composition as well as the genesis of some of the extended techniques and programmatic ideas. Copyright 2008 by Scott Meredith ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My deepest thanks go to Keith Johnson for his mentorship, guidance, and friendship. He has been instrumental in my development as a player, teacher, and citizen. I owe a great amount of gratitude to my colleagues John Wacker and Robert Murray for their continued support, encouragement, friendship, and belief in my dream. I owe a debt of gratitude to Lenora McCroskey for her knowledge of all things music and her willingness to drop everything for her students. -

Paired Syllables and Unequal Tonguing Patterns on Woodwinds in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries Bruce Haynes

Performance Practice Review Volume 10 Article 5 Number 1 Spring Tu ru or not Tu ru: Paired Syllables and Unequal Tonguing Patterns on Woodwinds in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries Bruce Haynes Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Haynes, Bruce (1997) "Tu ru or not Tu ru: Paired Syllables and Unequal Tonguing Patterns on Woodwinds in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 10: No. 1, Article 5. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199710.01.05 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol10/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 42 Bruce Haynes -> - As Hotteterre wrote, On observera seulement de ne point You must only observe never t prononcer Ru sur l& Tremblements; ni pronounce Ru on a shake, nor on sur deux Notes de suite, parceque le Ru two successive Notes, because Ru doit toujours &re m216 alternativement ought always to be intermixt alter- avec le TU.~ natively with TU' The R works when preceded by T,however (as in t dah). Quantz writes: I1 faut s'appliquer 2 prononcer trh fortement & distinctement la lettre r. sharply and clearly. It produces Cela fait 2 l'oreille le meme effet que the same effect on the ear as the lors qu'on se sen de di, en jouant de single-tongue di, although it does la simple langue: quoic)ue il ne not seem so to the player. -

Dynamics, Articulations, Slurs, Tempo Markings

24 LearnMusicTheory.net High-Yield Music Theory, Vol. 1: Music Theory Fundamentals Section 1.9 D YNAMICS , A RTICULATIONS , S LURS , T E M P O M ARKINGS Dynamics Dynamics are used to indicate relative loudness: ppp = pianississimo = very, very soft pp = pianissimo = very soft = piano = soft p mp = mezzo-piano = medium-soft mf = mezzo-forte = medium-loud f = forte = loud ff = fortissimo = very loud fff = fortississimo = very, very loud fp = forte followed suddenly by piano; also mfp, ffp, etc. sfz = sforzando = a forceful, sudden accent fz is forceful but not as sudden as sfz Articulations Articulations specify how notes should be performed, either in terms of duration or stress. Staccatissimo means extremely shortened duration. Staccato means shortened duration. Tenuto has two functions: it can mean full duration OR a slight stress or emphasis. Accent means stressed or emphasized (more than tenuto). Marcato means extremely stressed. An articulation of duration (staccatissimo, staccato, or tenuto) may combine with one of stress (tenuto, accent, or marcato). articulations of duration œÆ œ. œ- >œ œ^ & staccatto tenuto accent marcato staccattisimo articulations of stress Slurs Slurs are curved lines connecting different pitches. Slurs can mean: (1.) Bowings connect the notes as a phrase; (2.) for string instruments: play with one motion of the bow (up or down); (3.) for voice: sing with one syllable, or (4.) for wind instruments: don’t tongue between the notes. ? b2 œ œ œ œ ˙ b 4 Chapter 1: Music Notation 25 Fermatas Fermatas indicate that the music stops and holds the note until the conductor or soloist moves on.