The Controversy Over Bach's Trills: Towards a Reconciliation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education ______Ornamentation: an Introduction ______To the Mordent/Battement

Education _______ _______ Ornamentation: An Introduction _______ to the Mordent/Battement By Michael Lynn, One of my favorite ornaments is the I’ll use the French term [email protected] mordent. It often has a lively musical character but can also be drawn out to battement ... and mordent his is the second article I have make a more expressive ornament. interchangeably. written that covers ornaments that Players are often confused about weT might expect to encounter in Baroque the different names for various orna- 17th-century music, which may be music for the recorder. If you haven’t read ments, as well as the different signs played on recorder. the previous article in this series on used to signify them. To add to the Some of the terms we see being ornamentation, it may be helpful complications, the basic term mordent applied to this ornament are: to you to read the Fall 2020 AR was used to mean something com- • mordent installment, which covers trills and pletely different in the 19th century— • mordant appoggiaturas. different from its meaning in the • battement In this issue, we will discuss the Baroque period. • pincé. mordent or battement. In this series of articles on learning I’ll use the French term to interpret ornament signs, I focus on battement (meaning to “hit” or “beat”) music from the years 1680-1750. If you and mordent interchangeably look much outside of these boundaries, throughout this article—remember the situation gets more complicated. that they mean exactly the same thing. These dates encompass all of the Below is an example showing the Baroque recorder literature, with common signs and basic execution the exception of the early Baroque of the mordent. -

Second Grade Music Curriculum

Second Grade General Music Units September: October: November: December: January: Music Elements Music Elements Composition Performance Performance Rhythm Meter Rhythmic Composition Rhythmic Composition Performance Rhythmic Notation Intro to Meter Compose 8 measure Continue work on Practice using drum Top number rhythmic rhythmic Sticks& Pads Rhythmic Values Bottom number composition composition Counting Procedures -Mrs. Music May I? Bar Lines Review Dynamics Class work Practice performing -Rhythmic Pac Man Measure Add Dynamics original rhythmic -Musical Math Musical Rest to composition compositions Measure Completion Review Rough Performance Add other rhythm band Performance Draft with teacher Special Celebrations; instruments Special Celebrations: Performance Final draft (Songs & Activities) Perform composition (Song & activities) Special Celebrations: Graded Project Hanukkah for class Welcome Back songs (Songs & Activities) Kwanzaa Graded performance Character Ed Songs Fire Safety Songs Performance Christmas Performance Apple Songs Columbus Songs (Special Celebrations) Character Ed Special Celebrations: Butterfly Cycle Halloween Songs -Hiawatha Rhythm (Songs & Activities) th September 11 -Patriot Red Ribbon Songs Story -Month of the Year Rap Day Rhythm Pumpkin Patch -Thanksgiving Songs -Bundled Up September 17th- -I’m Thankful… -Martin Luther King Songs Constitution Day -Character Ed -Winter Songs February: March: April: May: June: Performance Music In Our Schools Music Elements Music Elements Performance Performance -

Keyboard Music

Prairie View A&M University HenryMusic Library 5/18/2011 KEYBOARD CD 21 The Women’s Philharmonic Angela Cheng, piano Gillian Benet, harp Jo Ann Falletta, conductor Ouverture (Fanny Mendelssohn) Piano Concerto in a minor, Op. 7 (Clara Schumann) Concertino for Harp and Orchestra (Germaine Tailleferre) D’un Soir Triste (Lili Boulanger) D’un Matin de Printemps (Boulanger) CD 23 Pictures for Piano and Percussion Duo Vivace Sonate für Marimba and Klavier (Peter Tanner) Sonatine für drei Pauken und Klavier (Alexander Tscherepnin) Duettino für Vibraphon und Klavier, Op. 82b (Berthold Hummel) The Flea Market—Twelve Little Musical Pictures for Percussion and Piano (Yvonne Desportes) Cross Corners (George Hamilton Green) The Whistler (Green) CD 25 Kaleidoscope—Music by African-American Women Helen Walker-Hill, piano Gregory Walker, violin Sonata (Irene Britton Smith) Three Pieces for Violin and Piano (Dorothy Rudd Moore) Prelude for Piano (Julia Perry) Spring Intermezzo (from Four Seasonal Sketches) (Betty Jackson King) Troubled Water (Margaret Bonds) Pulsations (Lettie Beckon Alston) Before I’d Be a Slave (Undine Smith Moore) Five Interludes (Rachel Eubanks) I. Moderato V. Larghetto Portraits in jazz (Valerie Capers) XII. Cool-Trane VII. Billie’s Song A Summer Day (Lena Johnson McLIn) Etude No. 2 (Regina Harris Baiocchi) Blues Dialogues (Dolores White) Negro Dance, Op. 25 No. 1 (Nora Douglas Holt) Fantasie Negre (Florence Price) CD 29 Riches and Rags Nancy Fierro, piano II Sonata for the Piano (Grazyna Bacewicz) Nocturne in B flat Major (Maria Agata Szymanowska) Nocturne in A flat Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. 19 in C Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. 8 in D Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. -

ASSIGNMENT and DISSERTATION TIPS (Tagg's Tips)

ASSIGNMENT and DISSERTATION TIPS (Tagg’s Tips) Online version 5 (November 2003) The Table of Contents and Index have been excluded from this online version for three reasons: [1] no index is necessary when text can be searched by clicking the Adobe bin- oculars icon and typing in what you want to find; [2] this document is supplied with direct links to the start of every section and subsection (see Bookmarks tab, screen left); [3] you only need to access one file instead of three. This version does not differ substantially from version 4 (2001): only minor alterations, corrections and updates have been effectuated. Pages are renumbered and cross-refer- ences updated. This version is produced only for US ‘Letter’ size paper. To obtain a decent print-out on A4 paper, please follow the suggestions at http://tagg.org/infoformats.html#PDFPrinting 6 Philip Tagg— Dissertation and Assignment Tips (version 5, November 2003) Introduction (Online version 5, November 2003) Why this booklet? This text was originally written for students at the Institute of Popular Music at the Uni- versity of Liverpool. It has, however, been used by many outside that institution. The aim of this document is to address recurrent problems that many students seem to experience when writing essays and dissertations. Some parts of this text may initially seem quite formal, perhaps even trivial or pedantic. If you get that impression, please remember that communicative writing is not the same as writing down commu- nicative speech. When speaking, you use gesture, posture, facial expression, changes of volume and emphasis, as well as variations in speed of delivery, vocal timbre and inflexion, to com- municate meaning. -

Bach: Goldberg Variations

The Choir of King’s College, Cambridge Final Logo Brand Extension Logo 06.27.12 BACH GOLDBERG VARIATIONS Parker Ramsay | harp PARKER RAMSAY Parker Ramsay was the first American to hold the post of Organ Scholar at King’s, from 2010–2013, following a long line of prestigious predecessors. Organ Scholars at King’s are undergraduate students at the College with a range of roles and responsibilities, including playing for choral services in the Chapel, assisting in the training of the probationers and Choristers, and conducting the full choir from time to time. The position of Organ Scholar is held for the duration of the student’s degree course. This is Parker’s first solo harp recording, and the second recording by an Organ Scholar on the College’s own label. 2 BACH GOLDBERG VARIATIONS Parker Ramsay harp 3 CD 78:45 1 Aria 3:23 2 Variatio 1 1:57 3 Variatio 2 1:54 4 Variatio 3 Canone all’Unisono 2:38 5 Variatio 4 1:15 6 Variatio 5 1:43 7 Variatio 6 Canone alla Seconda 1:26 8 Variatio 7 al tempo di Giga 2:24 9 Variatio 8 2:01 10 Variatio 9 Canone alla Terza 1:49 11 Variatio 10 Fughetta 1:45 12 Variatio 11 2:22 13 Variatio 12 Canone alla Quarta in moto contrario 3:21 14 Variatio 13 4:36 15 Variatio 14 2:07 16 Variatio 15 Canone alla Quinta. Andante 3:24 17 Variatio 16 Ouverture 3:26 18 Variatio 17 2:23 19 Variatio 18 Canone alla Sesta 1:58 20 Variatio 19 1:45 21 Variatio 20 3:10 22 Variatio 21 Canone alla Settima 2:31 23 Variatio 22 alla breve 1:42 24 Variatio 23 2:33 25 Variatio 24 Canone all’Ottava 2:30 26 Variatio 25 Adagio 4:31 27 Variatio 26 2:07 28 Variatio 27 Canone alla Nona 2:18 29 Variatio 28 2:29 30 Variatio 29 2:04 31 Variatio 30 Quodlibet 2:38 32 Aria da Capo 2:35 4 AN INTRODUCTION analysis than usual. -

The Form of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites Daniel E. Prindle University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Prindle, Daniel E., "The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 636. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/636 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2011 Master of Music in Music Theory © Copyright by Daniel E. Prindle 2011 All Rights Reserved ii THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________ Gary Karpinski, Chair _____________________________________ Miriam Whaples, Member _____________________________________ Brent Auerbach, Member ___________________________________ Jeffrey Cox, Department Head Department of Music and Dance iii DEDICATION To Michelle and Rhys. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the generous sacrifice made by my family. -

Performance Commentary

PERFORMANCE COMMENTARY . It seems, however, far more likely that Chopin Notes on the musical text 3 The variants marked as ossia were given this label by Chopin or were intended a different grouping for this figure, e.g.: 7 added in his hand to pupils' copies; variants without this designation or . See the Source Commentary. are the result of discrepancies in the texts of authentic versions or an 3 inability to establish an unambiguous reading of the text. Minor authentic alternatives (single notes, ornaments, slurs, accents, Bar 84 A gentle change of pedal is indicated on the final crotchet pedal indications, etc.) that can be regarded as variants are enclosed in order to avoid the clash of g -f. in round brackets ( ), whilst editorial additions are written in square brackets [ ]. Pianists who are not interested in editorial questions, and want to base their performance on a single text, unhampered by variants, are recom- mended to use the music printed in the principal staves, including all the markings in brackets. 2a & 2b. Nocturne in E flat major, Op. 9 No. 2 Chopin's original fingering is indicated in large bold-type numerals, (versions with variants) 1 2 3 4 5, in contrast to the editors' fingering which is written in small italic numerals , 1 2 3 4 5 . Wherever authentic fingering is enclosed in The sources indicate that while both performing the Nocturne parentheses this means that it was not present in the primary sources, and working on it with pupils, Chopin was introducing more or but added by Chopin to his pupils' copies. -

Basic Dynamic Markings

Basic Dynamic Markings • ppp pianississimo "very, very soft" • pp pianissimo "very soft" • p piano "soft" • mp mezzo-piano "moderately soft" • mf mezzo-forte "moderately loud" • f forte "loud" • ff fortissimo "very loud" • fff fortississimo "very, very loud" • sfz sforzando “fierce accent” • < crescendo “becoming louder” • > diminuendo “becoming softer” Basic Anticipation Markings Staccato This indicates the musician should play the note shorter than notated, usually half the value, the rest of the metric value is then silent. Staccato marks may appear on notes of any value, shortening their performed duration without speeding the music itself. Spiccato Indicates a longer silence after the note (as described above), making the note very short. Usually applied to quarter notes or shorter. (In the past, this marking’s meaning was more ambiguous: it sometimes was used interchangeably with staccato, and sometimes indicated an accent and not staccato. These usages are now almost defunct, but still appear in some scores.) In string instruments this indicates a bowing technique in which the bow bounces lightly upon the string. Accent Play the note louder, or with a harder attack than surrounding unaccented notes. May appear on notes of any duration. Tenuto This symbol indicates play the note at its full value, or slightly longer. It can also indicate a slight dynamic emphasis or be combined with a staccato dot to indicate a slight detachment. Marcato Play the note somewhat louder or more forcefully than a note with a regular accent mark (open horizontal wedge). In organ notation, this means play a pedal note with the toe. Above the note, use the right foot; below the note, use the left foot. -

Articulation from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Articulation From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Examples of Articulations: staccato, staccatissimo,martellato, marcato, tenuto. In music, articulation refers to the musical performance technique that affects the transition or continuity on a single note, or between multiple notes or sounds. Types of articulations There are many types of articulation, each with a different effect on how the note is played. In music notation articulation marks include the slur, phrase mark, staccato, staccatissimo, accent, sforzando, rinforzando, and legato. A different symbol, placed above or below the note (depending on its position on the staff), represents each articulation. Tenuto Hold the note in question its full length (or longer, with slight rubato), or play the note slightly louder. Marcato Indicates a short note, long chord, or medium passage to be played louder or more forcefully than surrounding music. Staccato Signifies a note of shortened duration Legato Indicates musical notes are to be played or sung smoothly and connected. Martelato Hammered or strongly marked Compound articulations[edit] Occasionally, articulations can be combined to create stylistically or technically correct sounds. For example, when staccato marks are combined with a slur, the result is portato, also known as articulated legato. Tenuto markings under a slur are called (for bowed strings) hook bows. This name is also less commonly applied to staccato or martellato (martelé) markings. Apagados (from the Spanish verb apagar, "to mute") refers to notes that are played dampened or "muted," without sustain. The term is written above or below the notes with a dotted or dashed line drawn to the end of the group of notes that are to be played dampened. -

J. S. BACH English Suites Nos

J. S. BACH English Suites Nos. 4–6 Arranged for Two Guitars Montenegrin Guitar Duo Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) with elegantly broken chords. This is interrupted by a The contrasting pair of Gavottes with a perky walking bass English Suites Nos. 4–6, BWV 809–811 sudden burst of semiquavers leading to a moment’s accompaniment brings in the atmosphere of a pastoral reflection before plunging into an extended and brilliant dance in the market square. The second Gavotte evokes (Arranged for two guitars by the Montenegrin Guitar Duo) fugal Allegro. Of the Préludes in the English Suites this is images of wind instruments piping together in rustic chorus. The English Suites is the title given to a set of six suites for Bach scholar, David Schulenberg has observed that while the longest and most elaborate. The Allemande which The Gigue, in 12/16 metre, is virtuosic in both keyboard believed to have been composed between 1720 the beginning of the Gigue presents a normal three-part follows is, in comparison, an oasis of calm, with superb compositional aspects and the technical demands on the and the early 1730s. During this period, Bach also explored fugal exposition, from then on, no more than two voices are contrapuntal writing and ingenious tonal modulations. The performers. Bach’s incomparable art of fugal writing is at the suite form in the six French Suites and the seven large heard at a time. Courante unites a French-style melodic line with a full stretch here, the second half representing, as in mirror suites under the title of Partitas (six in all) and an English Suite No. -

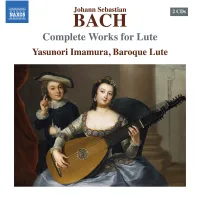

Imamura-Y-S03c[Naxos-2CD-Booklet

573936-37 bk Bach EU.qxp_573936-37 bk Bach 27/06/2018 11:00 Page 2 CD 1 63:49 CD 2 53:15 CD 2 Arioso from St John Passion, BWV 245 1Partita in E major, BWV 1006a 20:41 1Suite in E minor, BWV 996 18:18 # # Prelude 2:51 Consider, O my soul 2 Prelude 4:13 2 Betrachte, meine Seel’ Allemande 3:02 3 Loure 3:58 3 Betrachte, meine Seel’, mit ängstlichem Vergnügen, Consider, O my soul, with fearful joy, consider, Courante 2:40 4 Gavotte en Rondeau 3:29 4 Mit bittrer Lust und halb beklemmtem Herzen in the bitter anguish of thy heart’s affliction, Sarabande 4:24 5 Menuet I & II 4:43 5 Dein höchstes Gut in Jesu Schmerzen, thy highest good is Jesus’ sorrow. Bourrée 1:33 6 Bourrée 1:51 6 Wie dir auf Dornen, so ihn stechen, For thee, from the thorns that pierce Him, Gigue 2:27 Gigue 3:48 Die Himmelsschlüsselblumen blühn! what heavenly flowers spring. Du kannst viel süße Frucht von seiner Wermut brechen Thou canst the sweetest fruit from his wormwood gather, 7Suite in C minor, BWV 997 22:01 7Suite in G minor, BWV 995 25:15 Drum sieh ohn Unterlass auf ihn! then look on Him for evermore. Prelude 6:11 8 Prelude 3:11 8 Allemande 6:18 9 Fugue 7:13 9 Sarabande 5:28 0 Courante 2:35 Recitativo from St Matthew Passion, BWV 244b 0 $ $ Gigue & Double 6:09 ! Sarabande 2:50 Gavotte I & II 4:43 Ja freilich will in uns Yes! Willingly will we ! @ Prelude in C minor, BWV 999 1:55 Gigue 2:38 Ja freilich will in uns das Fleisch und Blut Yes! Willingly will we, Flesh and blood, Zum Kreuz gezwungen sein; Be brought to the cross; @ Fugue in G minor, BWV 1000 5:46 #Arioso from St John Passion, BWV 245 2:24 Je mehr es unsrer Seele gut, The harsher the pain Arioso: Betrachte, meine Seel’ Je herber geht es ein. -

Bach Festival the First Collegiate Bach Festival in the Nation

Bach Festival The First Collegiate Bach Festival in the Nation ANNOTATED PROGRAM APRIL 1921, 2013 THE 2013 BACH FESTIVAL IS MADE POSSIBLE BY: e Adrianne and Robert Andrews Bach Festival Fund in honor of Amelia & Elias Fadil DEDICATION ELINORE LOUISE BARBER 1919-2013 e Eighty-rst Annual Bach Festival is respectfully dedicated to Elinore Barber, Director of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute from 1969-1998 and Editor of the journal BACH—both of which she helped to found. She served from 1969-1984 as Professor of Music History and Literature at what was then called Baldwin-Wallace College and as head of that department from 1980-1984. Before coming to Baldwin Wallace she was from 1944-1969 a Professor of Music at Hastings College, Coordinator of the Hastings College-wide Honors Program, and Curator of the Rinderspacher Rare Score and Instrument Collection located at that institution. Dr. Barber held a Ph.D. degree in Musicology from the University of Michigan. She also completed a Master’s degree at the Eastman School of Music and received a Bachelor’s degree with High Honors in Music and English Literature from Kansas Wesleyan University in 1941. In the fall of 1951 and again during the summer of 1954, she studied Bach’s works as a guest in the home of Dr. Albert Schweitzer. Since 1978, her Schweitzer research brought Dr. Barber to the Schweitzer House archives (Gunsbach, France) many times. In 1953 the collection of Dr. Albert Riemenschneider was donated to the University by his wife, Selma. Sixteen years later, Dr. Warren Scharf, then director of the Conservatory, and Dr.