The First Two Laboratory Scientists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antony Van Leeuwenhoek, the Father of Microscope

Turkish Journal of Biochemistry – Türk Biyokimya Dergisi 2016; 41(1): 58–62 Education Sector Letter to the Editor – 93585 Emine Elif Vatanoğlu-Lutz*, Ahmet Doğan Ataman Medicine in philately: Antony Van Leeuwenhoek, the father of microscope Pullardaki tıp: Antony Van Leeuwenhoek, mikroskobun kaşifi DOI 10.1515/tjb-2016-0010 only one lens to look at blood, insects and many other Received September 16, 2015; accepted December 1, 2015 objects. He was first to describe cells and bacteria, seen through his very small microscopes with, for his time, The origin of the word microscope comes from two Greek extremely good lenses (Figure 1) [3]. words, “uikpos,” small and “okottew,” view. It has been After van Leeuwenhoek’s contribution,there were big known for over 2000 years that glass bends light. In the steps in the world of microscopes. Several technical inno- 2nd century BC, Claudius Ptolemy described a stick appear- vations made microscopes better and easier to handle, ing to bend in a pool of water, and accurately recorded the which led to microscopy becoming more and more popular angles to within half a degree. He then very accurately among scientists. An important discovery was that lenses calculated the refraction constant of water. During the combining two types of glass could reduce the chromatic 1st century,around year 100, glass had been invented and effect, with its disturbing halos resulting from differences the Romans were looking through the glass and testing in refraction of light (Figure 2) [4]. it. They experimented with different shapes of clear glass In 1830, Joseph Jackson Lister reduced the problem and one of their samples was thick in the middle and thin with spherical aberration by showing that several weak on the edges [1]. -

On the Development of Spinoza's Account of Human Religion

Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies Volume 5 Number 1 Spring 2014 Article 4 2014 On the Development of Spinoza’s Account of Human Religion James Simkins University of Pittsburgh Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal Recommended Citation Simkins, James "On the Development of Spinoza’s Account of Human Religion." Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies 5, no. 1 (2014). https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal/ vol5/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 52 James Simkins: On the Development of Spinoza’s Account of Human Religion JAMES SIMKINS graduated with philosophy, history, and history and philosophy of science majors from the University of Pittsburgh in 2013. He is currently taking an indefinite amount of time off to explore himself and contemplate whether or not to pursue graduate study. His academic interests include Spinoza, epistemology, and history from below. IMW Journal of Religious Studies Vol. 5:1 53 ‡ On the Development of Spinoza’s Account of Human Religion ‡ In his philosophical and political writings, Benedict Spinoza (1632-1677) develops an account of human religion, which represents a unique theoretical orientation in the early modern period.1 This position is implicit in many of Spinoza’s philosophical arguments in the Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect, the Short Treatise, and Ethics.2 However, it is most carefully developed in his Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (hereafter TTP).3 What makes Spinoza’s position unique is the fact that he rejects a traditional conception of religion on naturalistic grounds, while refusing to dismiss all religion as an entirely anthropological phenomenon. -

Menasseh Ben Israel and His World Brill's Studies in Intellectual History

MENASSEH BEN ISRAEL AND HIS WORLD BRILL'S STUDIES IN INTELLECTUAL HISTORY General Editor AJ. VANDERJAGT, University of Groningen Editorial Board M. COLISH, Oberlin College J.I. ISRAEL, University College, London J.D. NORTH, University of Groningen R.H. POPKIN, Washington University, St. Louis-UCLA VOLUME 15 MENASSEH BEN ISRAEL AND HIS WORLD EDITED BY YOSEF KAPLAN, HENRY MECHOULAN AND RICHARD H. POPKIN ^o fr-hw'* -A EJ. BRILL LEIDEN • NEW YORK • K0BENHAVN • KÖLN 1989 Published with financial support from the Dr. C. Louise Thijssen- Schoutestichting. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Menasseh Ben Israel and his world / edited by Yosef Kaplan, Henry Méchoulan and Richard H. Popkin. p. cm. -- (Brill's studies in intellectual history, ISSN 0920-8607 ; v. 15) Includes index. ISBN 9004091149 1. Menasseh ben Israel, 1604-1657. 2. Rabbis-Netherlands- -Amsterdam-Biography. 3. Amsterdam (Netherlands)-Biography. 4. Sephardim--Netherlands--Amsterdam--History--17th century. 5. Judaism--Netherlands--Amsterdam--History--17th century. I. Kaplan, Yosef. II. Popkin, Richard Henry, 1923- BM755.M25M46 1989 296'.092-dc20 89-7265 [B] CIP ISSN 0920-8607 ISBN 90 04 09114 9 © Copyright 1989 by E.J. Brill, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or translated in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, microfiche or any other means without written permission from the publisher PRINTED IN THE NETHERLANDS BY E.J. BRILI, CONTENTS Introduction, Richard H. Popkin vu A Generation of Progress in the Historical Study of Dutch Sephardic Jewry, Yosef Kaplan 1 The Jewish Dimension of the Scottish Apocalypse: Climate, Cove- nant and World Renewal, Arthur H. -

The Fingerprint Sourcebook

CHAPTER HISTORY Jeffery G. Barnes CONTENTS 3 1.1 Introduction 11 1.6 20th Century 3 1.2 Ancient History 17 1.7 Conclusion 4 1.3 221 B.C. to A.D. 1637 17 1.8 Reviewers 5 1.4 17th and 18th Centuries 17 1.9 References 6 1.5 19th Century 18 1.10 Additional Information 1–5 History C H A P T E R 1 CHAPTER 1 HISTORY 1.1 Introduction The long story of that inescapable mark of identity has Jeffery G. Barnes been told and retold for many years and in many ways. On the palm side of each person’s hands and on the soles of each person’s feet are prominent skin features that single him or her out from everyone else in the world. These fea- tures are present in friction ridge skin which leaves behind impressions of its shapes when it comes into contact with an object. The impressions from the last finger joints are known as fingerprints. Using fingerprints to identify indi- viduals has become commonplace, and that identification role is an invaluable tool worldwide. What some people do not know is that the use of friction ridge skin impressions as a means of identification has been around for thousands of years and has been used in several cultures. Friction ridge skin impressions were used as proof of a person’s identity in China perhaps as early as 300 B.C., in Japan as early as A.D. 702, and in the United States since 1902. 1.2 Ancient History Earthenware estimated to be 6000 years old was discov- ered at an archaeological site in northwest China and found to bear clearly discernible friction ridge impressions. -

Conservation Update for Robert Hooke's Micrographia

Slide 1 Conservation Update Robert Hooke’s Micrographia London:1667 Eliza Gilligan, Conservator for UVa Library [[email protected]] Hello, my name is Eliza Gilligan and I am the Conservator for University Library Collections at the University of Virginia. This slide show is a “re-broadcast” of a presentation I made at a library staff “Town Meeting” on September 16, 2011. I hope my notes to the slides fill in the gaps left by the transition from live presentation to this show, but if you have a question, please feel free to email me <[email protected]>. I’d like to share a little bit of information about the process of conservation treatment and also a little bit of information about what a unique opportunity conservation treatment provides in terms of examining the components of a book, using my recent treatment of Robert Hooke’s Micrographia as an example. Conservation of this title and many volumes from our circulating collections were made possible by a generous gift from Kathy Duffy, friend of the University Library Slide 2 What is Micrographia? The landmark publication that initiated the field of microscopy. The first edition was published in London in 1665. Robert Hooke described his use of a microscope for direct observation, provided text of his findings but most importantly, large illustrations to demonstrate his findings. The UVa Library copy is from the second issue printed in 1667. Eliza Gilligan, Conservator for UVa Library [[email protected]] This book was brought to my attention by a faculty member of the Rare Book School who uses it every year in her History of Illustration class. -

Tiny Love Baby Names Book 2016 Page 2

Tiny Love Baby Names Book 2016 page 2 Connecting with Your Little One: A Guide to the Perfect Name Choosing your baby’s name is never an easy task, so we at Tiny Love have created a special book to help you bond with your baby and find the perfect name. Our Tiny Love Baby Names Book is meant to accompany you through each stage before giving birth to your little one. Keep track of the names you like, read inspirational and informative articles, enjoy interactive resources and more! Amber Amethyst Aqua Aquamarine Ash page 3 Geographical Begin your baby’s life journey with a name inspired by a city or country that is meaningful to you! Tiny Thoughts You can bond with your baby by taking periodic walks. It’s a good Boys way to not only stay active, but to create a special bond between you and your baby. Bailey (Colorado, USA) Geneva (Switzerland) Berlin (Germany) Jackson (Mississippi, USA) Cairo (Egypt) Jordan Carson (California, USA) Kent (United Kingdom) What do you do to get outside Cody (Wyoming, USA) Lincoln (Nebraska, USA) during your pregnancy? Dakota (USA) London (England) Dallas (Texas, USA) Marquise (France) Dayton (Ohio, USA) Mitchell (South Dakota, USA) Devon (England) Orlando (Florida, USA) Diego (California, USA) Paris (France) Francisco (California, USA) Reno (Nevada, USA) Gary (Indiana, USA) Santiago (Chile) Tiny Love Baby Names Book 2016 Play Gyms | Mobiles & Soothers | Baby Gear | On The Go Toys | Baby Toys | Best Baby Toys TinyLove.com page 4 Geographical Be inspired by your favorite places and most adventurous explorations while discovering the perfect name for your new baby. -

Baruch Spinoza Chronology

Baruch Spinoza Chronology 1391 Spanish Jews are forced to convert to Catholicism for the sake of "social and sectarian uniformity." 1478 Establishment of the Spanish Inquisition, whose primary task is to convict and execute those found "judaizing." 1492 All practising Jews in Spain are given the choice to convert or be expelled. 1497 All Portuguese Jews (including Spinoza’s ancestors) are forced to convert. A steady stream of Jewish refugees begins to flow from Portugal. 1587/8 Spinoza’s father Michael is born in Vidigere, Portugal, to Isaac d’Espinoza 1609 Beginning of the twelve year truce between the United Provinces and Spain, effectively establishing political independence (after nearly a 100 year struggle) for the seven northern provinces as well as their (Protestant) sectarian separation from the (Catholic) southern provinces. 1618 Defenestration of Prague and beginning of the Thirty Years War. Calvinist-inspired coup d’état in the Dutch Republic, led by the Prince of Orange, leading to the execution of Oldenbarnevelt and imprisonment of Grotius. Uriel d’Acosta (or da Costa), a Portuguese “New Christian” who had returned to Judaism in Amsterdam but became disillusioned with the Jewish community, is excommunicated for the first time in Venice for denying the immortality of the soul and questioning the Mosaic authorship of the Torah, a decree later affirmed in Amsterdam in 1623 and renewed in 1633. 1619 Batavia, Java is established as headquarters of the Dutch East India Company. 1620 Francis Bacon writes Novum organum. 1621 Hostilities resume between Spain and the United Provinces. 1622 Probable date Spinoza’s father arrives in Amsterdam, probably from Nantes. -

Menasseh Ben Israel's Christian Connection: Henry Jessey and the Jews

MENASSEH BEN ISRAEL'S CHRISTIAN CONNECTION: HENRY JESSEY AND THE JEWS DAVID S. KATZ "He was of a middle Stature, and inclining to Fatness", an English con temporary described Rabbi Menasseh ben Israel, "He always wore his own Hair, which (many years before his Death) was very Grey; so that his Complexion being pretty fresh, his Demeanor Grace ful, and Comely, his Habit plain and decent, he Commanded an aweful Rev erence which was justly due to so venerable a Deportment: In short, he was un homme sans Passion, sans légèreté, mais Hélas/ sans opulence' '1. From his lodgings in the Strand, Menasseh sallied forth to meet politi cians, divines, intellectuals, and anyone who conceivably could help him to reach the goal of his English mission: an official authorization of the re- admission of the Jews to England after an exile of over three and a half centuries2. Menasseh had come to London in September 1655, and al though the Whitehall Conference of December failed to resolve the re- admission question, he remained in England for exactly two years in the vain hope of obtaining a formal written permission3. During his stay in London, he seems to have established himself, at least among gentiles, as a self-appointed ambassador of world Jewry and as a renowned expert in things Jewish. Menasseh received Ralph Cudworth, the Regius professor of Hebrew, and gave him a manuscript summarizing the Jewish objections to Christianity4. He discussed plans for a polyglot bible with Henry Thorndike5. He held further meetings with Henry Ol denburg, later secretary of the Royal Society; with Adam Boreel, the Con- 1 Menasseh ben Israel, Of The Term of Liß, ed. -

Art As Science: Scientific Illustration, 1490–1670 in Drawing, Woodcut and Copper Plate Cynthia M

Art as science: scientific illustration, 1490–1670 in drawing, woodcut and copper plate Cynthia M. Pyle Observation, depiction and description are active forces in the doing of science. Advances in observation and analysis come with advances in techniques of description and communication. In this article, these questions are related to the work of Leonardo da Vinci, 16th-century naturalists and artists like Conrad Gessner and Teodoro Ghisi, and 17th-century micrographers like Robert Hooke. So much of our thought begins with the senses. Before we forced to observe more closely so that he or she may accu- can postulate rational formulations of ideas, we actually rately depict the object of study on paper and thence com- feel them – intuit them. Artists operate at and play with municate it to other minds. The artist’s understanding is this intuitive stage. They seek to communicate their under- required for the depiction and, in a feedback mechanism, standings nonverbally, in ink, paint, clay, stone or film, or this understanding is enhanced by the act of depicting. poetically in words that remain on the intuitive level, The artist enters into the object of study on a deeper level mediating between feeling and thought. Reasoned ex- than any external study, minus subjective participation, plication involves a logical formulation of ideas for pres- would allow. entation to the rational faculties of other minds trained to Techniques (technai or artes as they were called in be literate and articulate. antiquity and the Middle Ages) for the execution of draw- Science (including scholarship) today or in the past ings were needed to depict nature accurately. -

Malpighi, Swammerdam and the Colourful Silkworm: Replication and Visual Representation in Early Modern Science

Annals of Science, 59 (2002), 111–147 Malpighi, Swammerdam and the Colourful Silkworm: Replication and Visual Representation in Early Modern Science Matthew Cobb Laboratoire d’Ecologie, CNRS UMR 7625, Universite´ Paris 6, 7 Quai St Bernard, 75005 Paris, France. Email: [email protected] Received 26 October 2000. Revised paper accepted 28 February 2001 Summary In 1669, Malpighi published the rst systematic dissection of an insect. The manuscript of this work contains a striking water-colour of the silkworm, which is described here for the rst time. On repeating Malpighi’s pioneering investi- gation, Swammerdam found what he thought were a number of errors, but was hampered by Malpighi’s failure to explain his techniques. This may explain Swammerdam’s subsequent description of his methods. In 1675, as he was about to abandon his scienti c researches for a life of religious contemplation, Swammerdam destroyed his manuscript on the silkworm, but not before sending the drawings to Malpighi. These gures, with their rich and unique use of colour, are studied here for the rst time. The role played by Henry Oldenburg, secretary of the Royal Society, in encouraging contact between the two men is emphasized and the way this exchange reveals the development of some key features of modern science — replication and modern scienti c illustration — is discussed. Contents 1. Introduction . 111 2. Malpighi and the silkworm . 112 3. The silkworm reveals its colours . 119 4. Swammerdam and the silkworm . 121 5. Swammerdam replicates Malpighi’s work . 124 6. Swammerdam publicly criticizes Malpighi . 126 7. Oldenburg tries to play the middle-man . -

De Felici1371.Pm4

Int. J. Dev. Biol. 44: 515-521 (2000) The rise of Italian embryology 515 The rise of embryology in Italy: from the Renaissance to the early 20th century MASSIMO DE FELICI* and GREGORIO SIRACUSA Department of Public Health and Cell Biology, University of Rome “Tor Vergata”, Rome, Italy. In the present paper, the Italian embryologists and their main the history of developmental biology were performed (see contributions to this science before 1900 will be shortly reviewed. "Molecularising embryology: Alberto Monroy and the origins of During the twentieth century, embryology became progressively Developmental Biology in Italy" by B. Fantini, in the present issue). integrated with cytology and histology and the new sciences of genetics and molecular biology, so that the new discipline of Embryology in the XV and XVI centuries developmental biology arose. The number of investigators directly or indirectly involved in problems concerning developmental biol- After the first embryological observations and theories by the ogy, the variety of problems and experimental models investi- great ancient Greeks Hippocrates, Aristotle and Galen, embryol- gated, became too extensive to be conveniently handled in the ogy remained asleep for almost two thousand years. In Italy at the present short review (see "Molecularising embryology: Alberto beginning of Renaissance, the embryology of Aristotle and Galen Monroy and the origins of Developmental Biology in Italy" by B. was largely accepted and quoted in books like De Generatione Fantini, in the present issue). Animalium and De Animalibus by Alberto Magno (1206-1280), in There is no doubt that from the Renaissance to the early 20th one of the books of the Summa Theologica (De propagatione century, Italian scientists made important contributions to estab- hominis quantum ad corpus) by Tommaso d’Aquino (1227-1274) lishing the morphological bases of human and comparative embry- and even in the Divina Commedia (in canto XXV of Purgatorio) by ology and to the rise of experimental embryology. -

Robert Hooke's Micrographia

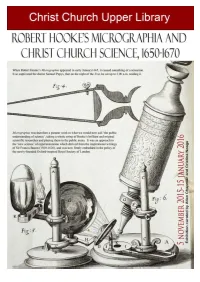

Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 is curated by Allan Chapman and Cristina Neagu, and will be open from 5 November 2015 to 15 January 2016. An exhibition to mark the 350th anniversary of the publication of Robert Hooke's Micrographia, the first book of microscopy. The event is organized at Christ Church, where Hooke was an undergraduate from 1653 to 1658, and includes a lecture (on Monday 30 November at 5:15 pm in the Upper Library) by the science historian Professor Allan Chapman. Visiting hours: Monday: 2.00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2.00 pm - 4.00 pm; Friday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm Article on Robert Hooke and Early science at Christ Church by Allan Chapman Scientific equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Photography Alina Nachescu Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Early Science at Christ Church, 1660-1670 Micrographia, Scheme 11, detail of cells in cork. Contents Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 Exhibition Catalogue Exhibits and Captions Title-page of the first edition of Micrographia, published in 1665. Robert Hooke’s Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 When Robert Hooke’s Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries thereupon appeared in early January 1665, it caused something of a sensation. It so captivated the diarist Samuel Pepys, that on the night of the 21st, he sat up to 2.00 a.m.