Tokyo Smart City Development in Perspective of 2020 Olympics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Koto Walking Map in Your Hand! Swing Your Arms Rhythmically in Time with Your Feet

Koto City, a warm-hearted town with a passion for sports FAQs about Walking Let’s start walking to keep you healthy. Enjoy walking without injury, in a good posture, and healthily Why don’t you try getting healthy and enjoy sightseeing spots in Q What is the proper walking form? A ▶▶▶ Pull your chin in and Stay upright and Koto City at the same time? look straight ahead puff out your chest We have created attractive 14 courses with the cooperation of residents who routinely walk for exercise. Let’s walk Koto City with the Koto Walking Map in your hand! Swing your arms rhythmically in time with your feet Put your heel on the ground first Then walk with a heel stride Kick the ground of about 5 to 7 cm bigger than usual with the base of your big toe Q When is a good time to hydrate ourselves? A ▶▶▶ ■1 Get hydrated frequently before feeling thirsty, such as before, during and after walking. ■2 As for what you drink, water is basically OK. It is better if you can also get an adequate amount of minerals (such as salt). ■3 Beverages containing caffeine, which has a diuretic effect such as coffee or tea, are not suitable for hydrating. Good things about walking Walking Style Calorie consumption by walking Before/After Walking What are the benefits of walking? What are appropriate clothes for walking? How many calories are consumed? How should we warm up before walking? FAQs about Q Q Q Q ▶▶▶ ■1 Prevent lifestyle-related ▶▶▶ ■1 Shirts and pants that dry quickly and absorb ▶▶▶ ■1 10-minute walking= calorie ▶▶▶ ■1 Stretch to warm up your body gradually and Walking A A A A diseases moisture well. -

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction The name Shanghai still conjures images of romance, mystery and adventure, but for decades it was an austere backwater. After the success of Mao Zedong's communist revolution in 1949, the authorities clamped down hard on Shanghai, castigating China's second city for its prewar status as a playground of gangsters and colonial adventurers. And so it was. In its heyday, the 1920s and '30s, cosmopolitan Shanghai was a dynamic melting pot for people, ideas and money from all over the planet. Business boomed, fortunes were made, and everything seemed possible. It was a time of breakneck industrial progress, swaggering confidence and smoky jazz venues. Thanks to economic reforms implemented in the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping, Shanghai's commercial potential has reemerged and is flourishing again. Stand today on the historic Bund and look across the Huangpu River. The soaring 1,614-ft/492-m Shanghai World Financial Center tower looms over the ambitious skyline of the Pudong financial district. Alongside it are other key landmarks: the glittering, 88- story Jinmao Building; the rocket-shaped Oriental Pearl TV Tower; and the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The 128-story Shanghai Tower is the tallest building in China (and, after the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the second-tallest in the world). Glass-and-steel skyscrapers reach for the clouds, Mercedes sedans cruise the neon-lit streets, luxury- brand boutiques stock all the stylish trappings available in New York, and the restaurant, bar and clubbing scene pulsates with an energy all its own. Perhaps more than any other city in Asia, Shanghai has the confidence and sheer determination to forge a glittering future as one of the world's most important commercial centers. -

Kagurazaka Campus 1-3 Kagurazaka,Shinjuku-Ku,Tokyo 162-8601

Tokyo University of Science Kagurazaka Campus 1-3 Kagurazaka,Shinjuku-ku,Tokyo 162-8601 Located 3 minutes’ walk from Iidabashi Station, accessible via the JR Sobu Line, the Tokyo Metro Yurakuchom, Tozai and Namboku Lines, and the Oedo Line. ACCESS MAP Nagareyama- Unga Otakanomori Omiya Kasukabe Noda Campus 2641 Yamazaki, Noda-shi, Chiba Prefecture 278-8510 Kanamachi Kita-Senju Akabane Tabata Keisei-Kanamachi Ikebukuro Nishi- Keisei-Takasago Nippori Katsushika Campus 6-3-1 Niijuku, Katsushika-ku, Nippori Oshiage Tokyo 125-8585 Asakusa Ueno Iidabashi Ochanomizu Shinjuku Kinshicho Akihabara Asakusabashi Kagurazaka Campus Kanda 1-3 Kagurazaka, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-8601 Tokyo ■ From Narita Airport Take the JR Narita Express train to Tokyo Station. Transfer to the JR Yamanote Line / Keihin-Tohoku Line and take it to Akihabara Station. Transfer to the JR Sobu Line and take it to Iidabashi Station. Travel time: about 1 hour 30 minutes. ■ From Haneda Airport Take the Tokyo Monorail Line to Hamamatsucho Station. Transfer to the JR Yamanote Line / Keihin-Tohoku Line and take it to Akihabara Station. Transfer to the JR Sobu Line and take it to Iidabashi Station. Travel time: about 45 minutes. ■ From Tokyo Station Take the JR Chuo Line to Ochanomizu Station. Transfer to the JR Sobu Line and take it to Iidabashi Station. Travel time: about 10 minutes. ■ From Shinjuku Station Take the JR Sobu Line to Iidabashi Station. Travel time: about 12 minutes. Building No.10 Building No.11 Annex Building No.10 Building No.5 CAMPUS MAP Annex Kagurazaka Buildings For Ichigaya Sta. Building No.11 Building No.12 Building No.1 1 Building No.6 Building No.8 Building Building No.13 Building Building (Morito Memorial Hall) No.7 No.2 No.3 3 1 The Museum of Science, TUS (Futamura Memorial Hall) & Building Mathematical Experience Plaza No.9 2 2 Futaba Building (First floor: Center for University Entrance Examinations) Tokyo Metro Iidabashi Sta. -

Railway Lines in Tokyo and Its Suburbs

Minami-Sakurai Hasuta Shin-Shiraoka Fujino-Ushijima Shimizu-Koen Railway Lines in Tokyo and its Suburbs Higashi-Omiya Shiraoka Kuki Kasukabe Kawama Nanakodai Yagisaki Obukuro Koshigaya Atago Noda-Shi Umesato Unga Edogawadai Hatsuisi Toyoshiki Fukiage Kita-Konosu JR Takasaki Line Okegawa Ageo Ichinowari Nanasato Iwatsuki Higashi-Iwatsuki Toyoharu Takesato Sengendai Kita-Koshigaya Minami-Koshigaya Owada Tobu-Noda Line Kita-Kogane Kashiwa Abiko Kumagaya Gyoda Konosu Kitamoto Kitaageo Tobu Nota Line Toro Omiya-Koen Tennodai Miyahara Higashi-Urawa Higashi-Kawaguchi JR Musashino Line Misato Minami-Nagareyama Urawa Shin-Koshigaya Minami- Kita- Saitama- JR Tohoku HonsenKita-Omiya Warabi Nishi-Kawaguchi Kawaguchi Kashiwa Kashiwa Hon-Kawagoe Matsudo Shin- Gamo Takenozuka Yoshikawa Shin-Misato Shintoshin Nishi-Arai Umejima Mabashi Minoridai Gotanno Yono Kita-Urawa Minami-Urawa Kita-Akabane Akabane Shinden Yatsuka Shin- Musashiranzan Higashi-Jujo Kita-Matsudo Shinrin-koenHigashi-MatsuyamaTakasaka Omiya Kashiwa Toride Yono Minami- Honmachi Yono- Matsubara-Danchi Shin-Itabashi Minami-FuruyaJR Kawagoe Line Musashishi-Urawa Kita-Toda Toda Toda-Koen Ukima-Funato Kosuge JR Saikyo Line Shimo Matsudo Kita-Sakado Kita- Shimura- Akabane-Iwabuchi Soka Masuo Ogawamachi Naka-Urawa Takashimadaira Shiden Matsudo- Yono Nishi-Takashimadaira Hasune Sanchome Itabashi-Honcho Oji Kita-senju Kami- Myogaku Sashiogi Nisshin Nishi-Urawa Daishimae Tobu Isesaki Line Kita-Ayase Kanamachi Hongo Shimura- Jujo Oji-Kamiya Oku Sakasai Yabashira Kawagoe Shingashi Fujimino Tsuruse -

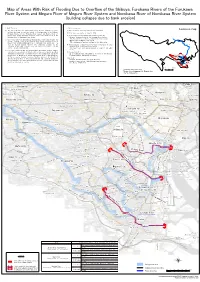

Map of Areas with Risk of Flooding Due to Overflow of the Shibuya

Map of Areas With Risk of Flooding Due to Overflow of the Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System (building collapse due to bank erosion) 1. About this map 2. Basic information Location map (1) This map shows the areas where there may be flooding powerful enough to (1) Map created by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government collapse buildings for sections subject to flood warnings of the Shibuya, (2) Risk areas designated on June 27, 2019 Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of Meguro River System and those subject to water-level notification of the (3) River subject to flood warnings covered by this map Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System. Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System (The flood warning section is shown in the table below.) (2) This river flood risk map shows estimated width of bank erosion along the Meguro River of Meguro River System Shibuya, Furukawa rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of (The flood warning section is shown in the table below.) Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System resulting from the maximum assumed rainfall. The simulation is based on the (4) Rivers subject to water-level notification covered by this map Sumida River situation of the river channels and flood control facilities as of the Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System time of the map's publication. (The water-level notification section is shown in the table below.) (3) This river flood risk map (building collapse due to bank erosion) roughly indicates the areas where buildings could collapse or be washed away when (5) Assumed rainfall the banks of the Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Up to 153mm per hour and 690mm in 24 hours in the Shibuya, Meguro River of Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River Furukawa, Meguro, Nomikawa Rivers basin Shibuya River,Furukawa River System are eroded. -

Weekender July-2021 Web.Pdf

JUL-AUG 2021 FULL SPEED AHEAD SUMMER SIPPERS TIME IS RUNNING OUT Takuya Haneda hopes to paddle his New and true Japanese liqueurs that Japan’s slapdash love affair with SDGs canoe to gold at Tokyo 2020 will hold the Tokyo heat at bay is anything but sustainable — 2 — Weekender_August_Master_002.indd 2 2018/07/24 11:41 CONTENTS RADAR IN-DEPTH TRAVEL THIS MONTH’S HEAD TURNERS COFFEE-BREAK READS WHERE TO GO 8 AREA GUIDE: TOKYO’S LUMBERYARD 20 BALLET IN THE TIME OF CORONA 46 SHONAI SHRINE Once Tokyo’s center for all things wood, How National Ballet of Japan’s new artistic Embark on small adventures on the grounds Shin-Kiba now brightens up at night as a director Miyako Yoshida stays on her toes. of a former Yamagata castle. popular entertainment hub. 23 KYOTO IN SYMPHONY 50 SPORTS PARADISE 10 STYLE: ODE TO THE BIRDS Composer Marios Joannou Elia orchestrates a Traditional and modern sports have deep Photographer and filmmaker Boa Campbell masterpiece of sound dedicated to Kyoto. roots in Kyushu’s Miyazaki Prefecture. takes us on a flight through Tokyo’s world of modern fashion. 26 A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A SHAMISEN 52 KYUSHU BY TRAIN MAKER Escape to these iconic locales with 16 SHOP JAPAN: BEST OF THE BEACH The designer of Tokyo 2020’s official shamisen assistance from the JR Kyushu Rail Pass. These Japan-made summer accessories spreads the word about the native instrument. help anyone stay cool and look stylish on their next seaside excursion. 30 ON IMPULSE GUIDE Special effects makeup artist extraordinnaire CULTURE ROUNDUP 18 TRENDS: 5 JAPANESE LIQUEURS Amazing Jiro takes TW inside his twisted world. -

The Budo Charter (Budo Kensho)

The Budo Charter externalise the spirit underlying budo. They must do their best at all times, (Budo Kensho) winning with modesty, accepting defeat gracefully and constantly exhibiting self-control. Budo, the Japanese martial ways, have their origins in the age-old martial spirit of Japan. Through centuries of historical and social change, these forms of ARTICLE 4: DOJO (Training Hall) traditional culture evolved from combat techniques (jutsu) into ways of self- The dojo is a special place for training the mind and body. In the dojo, budo development (do). practitioners must maintain discipline, and show proper courtesies and respect. The dojo should be a quiet, clean, safe and solemn environment. Seeking the perfect unity of mind and technique, budo has been refined and cultivated into ways of physical training and spiritual development. The study ARTICLE 5: TEACHING of budo encourages courteous behaviour, advances technical proficiency, Teachers of budo should always encourage others to also strive to better strengthens the body, and perfects the mind. Modern Japanese have inherited themselves and diligently train their minds and bodies, while continuing to traditional values through budo which continue to play a significant role in the further their understanding of the technical principles of budo. Teachers should formation of the Japanese personality, serving as sources of boundless energy not allow focus to be put on winning or losing in competition, or on technical and rejuvenation. As such, budo has attracted strong interest internationally, ability alone. Above all, teachers have a responsibility to set an example as and is studied around the world. role models. -

Notice Concerning Transfer and Acquisition of Assets, and Related Cancellation of Lease and Leasing of Assets

October 27, 2020 For Immediate Release Real Estate Investment Trust Securities Issuer: NIPPON REIT Investment Corporation 1-18-1 Shimbashi, Minato-ku, Tokyo Toshio Sugita Executive Officer (Securities Code: 3296) Asset Management Company: Sojitz REIT Advisors K.K. Toshio Sugita President, Director & CEO Contact: Takahiro Ishii General Manager Corporate Planning Department Finance & Planning Division (TEL: +81-3-5501-0080) Notice Concerning Transfer and Acquisition of Assets, and Related Cancellation of Lease and Leasing of Assets NIPPON REIT Investment Corporation (“NIPPON REIT”) announces that Sojitz REIT Advisors K.K. (“SRA”), which is entrusted to manage the assets of NIPPON REIT, today decided on the following transfer and acquisition of assets (respectively the “Transfer” and the “Acquisition”, and collectively the “Transactions”). Furthermore, SRA decided cancellation of lease and leasing of asset related to the Transactions as well. The tenants of the properties to be acquired comply with the tenant screening criteria described in the Report on the Management Structure and System of the Issuer of Real Estate Investment Trust Units and Related Parties dated September 30, 2020. 1. Overview of To-be-acquired assets and To-be-transferred assets (i). Overview of To-be-transferred assets Scheduled Property Real estate in trust transfer price Transfer counterparty Scheduled Number Location (Buyer) transfer (Property Name) (million yen) (Note1) (Note3) date (Note2) Toshima Nov. 17, A-34 Mejiro NT Building 3,920 Not disclosed (Note4) Ward, Tokyo 2020 Koto Ward, Nov. 17, A-36 Mitsui Woody Building 3,246 Not disclosed (Note4) Tokyo 2020 Nov. 17, C-2 Komyoike Act Sakai, Osaka 2,158 Not disclosed (Note4) 2020 Total 9,324 1 (ii). -

List of Training Venues for Olympic Games Tokyo 2020 (As of 20 February 2020)

List of Training Venues for Olympic Games Tokyo 2020 (As of 20 February 2020) ■ indicates update from the last version Document subject to change Standalone Training Venues Please refer to "Standalone Training Venue Visit Policy" on Tokyo 2020 Connect if you are interested in visiting these facilities. Sport Discipline Venue Name Address Open Period during Games time Comment Water Polo(men) Tokyo Metropolitan Gymnasium 1-17-1 Sendagaya,Shibuya-ku,Tokyo From 14 Jul. to 9 Aug. 2020 Closed (under construction) Aquatics Water Polo (Women) Musashino Forest Sport Plaza 290-11 Nishimachi, Chofu-shi, Tokyo From 14 Jul. to 8 Aug. 2020 Track & Field Edogawa City Track & Field Stadium 2-1-1 Seishincho,Edogawa-ku,Tokyo From 14 Jul. to 8 Aug. 2020 Athletics Track & Field Yoyogi Park Athletic Field 2-1 Yoyogikamizonocho,Shibuya-ku,Tokyo From 14 Jul. to 8 Aug. 2020 Softball: 14 to 16 Jul., 2020 Baseball/ Softball Ota Stadium 1-2-10 Tokai,Ota-ku,Tokyo Baseball: 18 Jul. to 8 Aug. 2020 Baseball/ Softball Baseball Hosei University’s Kawasaki General Ground 4-1 Kizukiomachi,Nakahara-ku,Kawasaki-shi,Kanagawa From 14 Jul. to 26 Jul. 2020 Baseball Nippon Sport Science University Yokohama Kenshidai Campus 1221-1 Kamoshida-cho, Aoba-ku, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa From 14 Jul. to 1 Aug. 2020 Softball Nippon Sport Science University Tokyo Setagaya Campus 7-1-1 Fukasawa,Setagaya-ku,Tokyo From 14 to 19, and 24 Jul. 2020 Basketball Tokyo Big Sight 3-11-1 Ariake, Koto-ku, Tokyo From 14 Jul. to 9 Aug. 2020 Not disclosed for visit ( in use for events) Basketball 3x3 Basketball Chuo Comprehensive Sports Center 2-59-1 Nihonbashihamacho, Chuo-ku,Tokyo From 14 Jul. -

Lympic Proportions Oby Régis Arnaud Author Régis Arnaud

COVER STORY • “Amazing Tokyo” — Beyond 2020 • 5-3 lympic Proportions OBy Régis Arnaud Author Régis Arnaud Olympic Enthusiasm one-third of the country’s annual budget for 1964, and 3.4% of Japan’s GDP. Most of this investment was spent in the layout of the The 2020 Tokyo Olympics seem to have become the rationale for Tokyo-Osaka Shinkansen bullet train (which started only nine days any political and economic decision in Japan. Each public speech before the opening ceremony of the 1964 Olympics), the Shuto must now mention at some point the 2020 Olympics to be taken kosoku (the suspended highway that runs above the streets of seriously. Most policies seem to have this event as a final goal. At the Tokyo) (Photo 1), and many subway lines. In the following years, same time, the country is bathing in nostalgia for the 1964 Tokyo Japan laid down the Meishin Nagoya-Osaka highway (1965), the Olympics, by almost all accounts a stunning success for Japan and Tomei Tokyo-Osaka highway (1969), and, last, the Sanyo Shinkansen Tokyo. between Osaka and Fukuoka (1975). In short, much of Japan’s It is indeed inevitable to put in parallel the 1964 Olympics and the transport infrastructure of today rests on the foundations of what 2020 Olympics. The decision to give the first Olympics to Tokyo was was drawn up at the time and on the occasion of the 1964 Tokyo announced in 1959, when the prime minister was no other than Olympics. Nobusuke Kishi, the very grandfather of current Prime Minister The impact of this event was also felt on the global stage. -

Fiscal Period Business Report Th (Statement of Financial Performance) 19 December 1, 2014 – May 31, 2015

Fiscal Period Business Report th (Statement of Financial Performance) 19 December 1, 2014 – May 31, 2015 The Daiwa Office Investment Corporation logo symbolizes hospitality with an open door and the desire to be a bright and open investment corporation. We will continue to aim to be a highly-transparent investment corporation that is further cherished and trusted by our investors and tenants. 6-2-1 Ginza, Chuo Ward, Tokyo http://www.daiwa-of_ce.co.jp/en/ I. Overview of Daiwa Office Investment Corporation To Our Investors We would like to express our deep gratitude to all our unitholders for your support of Daiwa Office Investment Corporation (DOI). In the 19th Fiscal Period, DOI posted operating revenues of 10,387 million yen and operating income of 4,770 million yen. Our distribution per unit for the 19th Fiscal Period is 9,142 yen, an increase by 886 yen from the 18th Fiscal Period. See page 4 for financial and management highlights Average contract rent at the end of the 19th Fiscal Period increased 875 yen from the end of the previous fiscal period to 18,674 yen and greatly contributed to further internal growth. Rent revisions contributed to 5 million yen increase in monthly contracted rents from the end of the previous fiscal period, which was a 5.2% increase rate for the average monthly rent. Tenants moving in/out led to 14 million yen of net increase in monthly contracted rents from the end of the previous fiscal period, and the increase rate for the average monthly rent increased 9.2% due to replacement of tenants. -

Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games Sustainability Plan Version 2

Tokyo 2020 Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games Sustainability Plan Version 2 June 2018 The Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games Preface Sustainability Plan The Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games Sustainability Plan (hereinafter referred to as the “Plan”) has been developed by the Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games (hereinafter referred to as the “Tokyo 2020”): ・ (while) Respecting the approach to focus on sustainability and legacy in all aspects of the Olympic Games and within the Olympic Movement’s daily operations outlined in Olympic Agenda 20201, ・ To maximise consideration for sustainability of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games (hereinafter referred to as the “Tokyo 2020 Games” or simply the “Games”, if appropriate), and ensure that the delivery of the Games contributes to sustainable development. The Plan aims to: ・ Specify the Tokyo 2020’s recognition of the relationship between the delivery of the Tokyo 2020 Games and sustainable development (sustainability) and how Tokyo 2020 intends to contribute to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)2 through the delivery of the Games, ・ Set out policies, goals and measures for Tokyo 2020, delivery partners* and other parties involved in the Games to take for sustainable Games planning and operations, ・ Provide information related to sustainable planning and operations of the Tokyo 2020 Games for various people who are interested in the Tokyo 2020 Games to communicate with those involved in the Games, ・ Become a learning legacy that will be used for sustainable Olympic and Paralympic Games planning and operations by those involved in the future Olympic and Paralympic Games, and ・ Be referred to and used by people in Japan and the world to pursue approaches to sustainable development.