Baseline Study Report|PCCP WI 6576 Prime Contract No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Typhoon Bopha (Pablo)

N MA019v2 ' N 0 ' Silago 3 0 ° 3 0 ° 1 0 Philippines 1 Totally Damaged Houses Partially Damaged Houses Number of houses Number of houses Sogod Loreto Loreto 1-25 2-100 717 376 Loreto Loreto 26-250 101-500 San Juan San Juan 251-1000 501-1000 1001-2000 1001-2000 2001-4000 2001-4000 Cagdianao Cagdianao 1 N ° N San Isidro 0 ° Dinagat 1 0 Dinagat San Isidro Philippines: 1 5 Dinagat (Surigao del Norte) Dinagat (Surigao 5 del Norte) Numancia 280 Typhoon Bopha Numancia Pilar Pilar Pilar Pilar (Pablo) - General 547 Surigao Dapa Surigao Dapa Luna General Totally and Partially Surigao Surigao Luna San San City Francisco City Francisco Dapa Dapa Damaged Housing in 1 208 3 4 6 6 Placer Placer Caraga Placer Placer 10 21 Bacuag Mainit Bacuag (as at 9th Dec 5am) Mainit Mainit 2 N 1 Mainit ' N 0 ' 3 0 ° Map shows totally and partially damaged 3 9 Claver ° 9 Claver housing in Davao region as of 9th Dec. 33 Bohol Sea Kitcharao Source is "NDRRMC sitrep, Effects of Bohol Sea Kitcharao 10 Typhoon "Pablo" (Bopha) 9th Dec 5am". 3 Province Madrid Storm track Madrid Region Lanuza Tubay Cortes ! Tubay Carmen Major settlements Carmen Cortes 513 2 127 21 Lanuza 10 Remedios T. Tandag Tandag City Tandag Remedios T. Tandag City Romualdez 3 Romualdez 15 N ° N 13 9 ° Bayabas 9 Buenavista Sibagat Buenavista Sibagat Bayabas Carmen Carmen Butuan 53 200 Butuan 127 Butuan 21 Butuan 3 City City Cagwait Cagwait 254 Prosperidad 12 17 Gingoog Buenavista 631 Gingoog Buenavista Marihatag Marihatag 43 1 38 19 San Las Nieves San Agustin Las Nieves Agustin 57 Prosperidad 56 2 4 0 10 -

NDRRMC Update Progressl Report on the Effects of SLPA in CARAGA

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Center, Camp Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo, Quezon City, Philippines NDRRMC UPDATE Progress Report on the Effects of Shallow Low Pressure Area (SLPA) in CARAGA Region Releasing Officer USEC BENITO T. RAMOS Executive Director, NDRRMC and Administrator, OCD DATE: 19 February 2011, 2:00 PM Sources: OCD – CARAGA, Agusan del Sur PIA, PNP and LGU I. SITUATION OVERVIEW Profile of the Incident • Due to Shallow Low Pressure Area (SLPA), CARAGA Region is experiencing cloudy skies but no rain since last night 18 February 2011. The following incidents were observed and monitored: AGUSAN DEL SUR • River systems in the Province of Agusan del Sur are now increasing in water level particularly in Gibong River in Prosperidad and Wawa River in Sibagat • Portion of National Highway in Bunawan, Agusan del Sur is flooded but still passable to heavy vehicles • Few houses in Los Arcos, Prosperidad, Agusan del Sur are still underwater. Road section in the same area is submerged with water but passable. • Pre-emptive evacuations were conducted in the municipalities of San Francisco (Brgys. 1 and 2) and Rosario (Brgys. Poblacion, Libuac and Cabanto). Evacuees are now housed at the Municipal Gym, Agusan del Sur National High School (San Francisco) and Municipal Training Center (Rosario) AGUSAN DEL NORTE • Flights of Cebu Pacific and Philippine Airlines in Butuan City resumed this morning. SURIGAO DEL SUR • Road section from San Vicente to Poblacion, Barobo, Surigao del Sur is now passable to all types of vehicles • Awa-Azpetia-lianga road incurred slip at the side portion with 26 meters length, 5 meters wide and average depth of 3 meters. -

DILEEP 2009-2016 Rona Start.Xls

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT Caraga Regional Office DOLE Integrated Livelihood and Emergency Employment Program(DILEEP) - KABUHAYAN Beneficiaries Grant ACP Beneficiaries Project Title Date Released Female Total Amount Check No. Date AGUSAN DEL NORTE 1 BLGU Sto.Rosario, Rice Trading and Grocery Magallanes, Agusan del Project 162 1,000,000.00 1049449 5/9/2017 May 15, 2017 Norte/Lauan Village Workers Association 2 Eastern Suburb Tricyle Motor Spare Parts and Operators and Drivers Accessories Trading 45 438,693.00 Association (ESTODA) Ampayon, Butuan City 3 BLGU-Dulag,Butuan Rice and Corn Trading City/Dulag Womens 75 750,000.00 1049876 6/30/2017 November 6,2017 Association 4 BLGU-Binuangan, Tubay Consumer Store Agusan del Norte/Binuangan Farmers 25 108,501.00 1049887 6/30/2017 November 7, 2017 and Fisherfolk Association 5 BLGU-Jagupit, Santiago Motor Spare Parts and Agusan del Accessories Trading Norte/Cabadbaran Santiago Tricycle 33 307,700.00 1049886 6/30/2017 November 13, 2017 Operators and Drivers Association (CASATODA) 6 BLGU-Manapa, Milkfish in Marine Cage Buenavista Agusan del Project Norte/Manapa Homebase 35 55 485,350.00 1081421 10/8/2017 November 13, 2017 Workers Association 7 BLGU San Antonio, RTR, Green Charcoal Project Agusan del Norte/Nagkahi-usang 120 120 250,000.00 Kababaihan sa Antonio (NAKSA) 8 BLGU-Mat-i, Las Nieves, SEWING Agusan del Norte/Barangay Mat-i 50 275,000.00 Women's Association (Las Nieves) 9 Mabuhay Small Coconut Rice and Corn Retailing Farmers Association and Wholesaling 25 -

Mines and Geosciences Bureau Caraga Regional Office Consolidated Mineral Resources Data on Sales in Caraga Region Cy-2017

MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU CARAGA REGIONAL OFFICE CONSOLIDATED MINERAL RESOURCES DATA ON SALES IN CARAGA REGION CY-2017 UNIT 2% EXCISE TAX (in 5% ROYALTY TAX (in NO. OF Country of Mineral Commodity/ Mining Company Location Volume Gross Value in US$ Gross Value in Php IP SHARES USED PhP) PhP) SHIPMENTS Destination Gold Philsaga Mining Corp. Bunawan & Rosario, Agusan del Sur kg 2,656.27 116,596,857.36 5,883,703,729.65 117,674,074.59 N/A 22 58,837,037.30 Hong Kong Greenstone Resources Corp. Mainit & Tubod, Surigao del Norte kg 287.06 12,369,409.73 623,303,449.79 12,466,069.00 N/A 3 6,233,034.50 Switzerland TOTAL 2,943.33 128,966,267.09 6,507,007,179.44 130,140,143.59 - 65,070,071.79 Silver Philsaga Mining Corp. Bunawan & Rosario, Agusan del Sur kg 565.25 338,001.75 17,053,051.96 341,061.04 N/A 22 170,530.52 Hong Kong Greenstone Resources Corp. Mainit & Tubod, Surigao del Norte kg 298.97 173,627.79 8,773,551.72 175,471.03 N/A 3 87,735.52 Switzerland TOTAL 864.21 511,629.54 25,826,603.68 516,532.07 - 258,266.04 Nickel Ore Taganito Mining Corp Claver, Surigao del Norte WMT 3,052,122.00 82,390,844.15 4,154,730,095.67 83,094,601.91 207,736,504.78 57 41,547,300.96 Japan and China TMC - THPAL Feed Claver, Surigao del Norte WMT 4,589,953.00 31,288,050.82 1,575,460,958.00 31,509,219.17 78,773,047.90 12 OTPs THPAL Surigao, Phil. -

Directory of Participants 11Th CBMS National Conference

Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Academe Dr. Tereso Tullao, Jr. Director-DLSU-AKI Dr. Marideth Bravo De La Salle University-AKI Associate Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 Ms. Nelca Leila Villarin E-Mail: [email protected] Social Action Minister for Adult Formation and Advocacy De La Salle Zobel School Mr. Gladstone Cuarteros Tel No: (02) 771-3579 LJPC National Coordinator E-Mail: [email protected] De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 7212000 local 608 Fax: 7248411 E-Mail: [email protected] Batangas Ms. Reanrose Dragon Mr. Warren Joseph Dollente CIO National Programs Coordinator De La Salle- Lipa De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 756-5555 loc 317 Fax: 757-3083 Tel No: 7212000 loc. 611 Fax: 7260946 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Camarines Sur Brother Jose Mari Jimenez President and Sector Leader Mr. Albino Morino De La Salle Philippines DEPED DISTRICT SUPERVISOR DEPED-Caramoan, Camarines Sur E-Mail: [email protected] Dr. Dina Magnaye Assistant Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Cavite Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 E-Mail: [email protected] Page 1 of 78 Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Ms. Rosario Pareja Mr. Edward Balinario Faculty De La Salle University-Dasmarinas Tel No: 046-481-1900 Fax: 046-481-1939 E-Mail: [email protected] Mr. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ……………………………. 1 Chapter 1 University Background ……………. 7 1.1 History ……………………………. 7 1.2 Vision ……………………………. 11 1.3 Mission ……………………………. 11 1.4 General Mandate ……………………. 12 1.5 Core Values ……………………………. 12 1.6 Functions and Objectives ……………. 12 1.6.a. General Objectives ………….... 12 1.6.b. Specific Functions and Objectives. 14 Instruction …………………….. 14 Research …………………….. 14 Extension …………………….. 15 Production …………………….. 15 1.7 University Seal and Code …………….. 16 1.8 Credo and Philosophy …………….. 16 1.8.a Our Credo …………………….. 16 1.8.b. Our Philosophy …………….. 16 1.9 University Hymn …………………….. 17 1.10 Campus Map (Main Campus) .………... 18 1.11 Campus Map (Cabadbaran Campus) ... 19 Chapter 2 Academic Policies ……………………... 20 2.1 Admission and Registration ……… 20 2.2 Academic Load ……………………… 28 2.3 Curricular Changes ……………………… 29 2.4 Scholastic Standing ……………………… 31 2.5 Major Examination and Undergraduate Thesis ……………………… 39 2.6 Grading System and Academic Recognition ……………………… 41 2.7 Incomplete Grades and Removal Examination ……………………… 42 2.8 Retention Policies ……………………… 43 2.9 Academic Completion……………………. 45 Chapter 3 Student Services (General Principles)…. 47 3.1 Application ……………………………… 47 CSU Student Handbook 1 3.2 Implementation ……………………… 48 3.3 Students Rights and Responsibilities….. 49 3.3.a Rights of Students ……………… 49 3.3.b Responsibilities of Students …… 51 Chapter 4 Student Welfare ……………………… 51 4.1 Scope ……………………………… 51 4.2 Guidance and Counselling Services…… 52 4.3 Health and Food Services ……………… 53 4.4 Scholarship and Financial Assistance… 54 4.5 Housing and Other Amenities…………… 55 4.6 Security Services…………………………. 55 4.7 Library Services…………………………… 56 Chapter 5 Student Development ……………… 58 5.1 Scope ……………………………… 58 5.2 Student Organization ……………… 58 5.3 Student Publication ……………………… 59 5.4 Student Co-curricular and Extra Curricular Activities ……………… 60 Chapter 6 Students Conduct and Discipline …… 61 6.1 Scope ……………………………… 61 6.2 Student Conduct and Discipline ……… 61 6.3 The CSU Code of Student Conduct……. -

State Universities and Colleges 963 R

STATE UNIVERSITIES AND COLLEGES 963 R. BANGSAMORO AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO (BARMM) R.1. ADIONG MEMORIAL POLYTECHNIC STATE COLLEGE For general administration and support, support to operations, and operations, including locally-funded project(s), as indicated hereunder....................................................................................................................P 155,730,000 ============= New Appropriations, by Program ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ Current Operating Expenditures ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ Maintenance and Other Personnel Operating Capital Services Expenses Outlays Total ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ PROGRAMS 100000000000000 General Administration and Support P 10,597,000 P 14,495,000 P P 25,092,000 200000000000000 Support to Operations 2,000 840,000 29,153,000 29,995,000 300000000000000 Operations 18,863,000 13,594,000 68,186,000 100,643,000 ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ HIGHER EDUCATION PROGRAM 18,863,000 7,411,000 68,186,000 94,460,000 ADVANCED EDUCATION PROGRAM 574,000 574,000 RESEARCH PROGRAM 1,872,000 1,872,000 TECHNICAL ADVISORY EXTENSION PROGRAM 3,737,000 3,737,000 ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ TOTAL NEW APPROPRIATIONS P 29,462,000 P 28,929,000 P 97,339,000 P 155,730,000 ================ ================ ================ ================ New Appropriations, by Programs/Activities/Projects (Cash-Based) ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ -

Pdf | 351.29 Kb

Areas Having Public Storm Warning Signal PSWS # Mindanao Signal No. 1 Surigao del Norte (30-60 kph winds may be expected in at Siargao Is. least 36 hours) Surigao del Sur Dinagat Province Agusan del Norte Agusan del Sur Davao Oriental Compostella Valley Estimated rainfall amount is from 5 - 15 mm per hour (moderate - heavy) within the 300 km diameter of the Tropical Depression Tropical Depression "AGATON" will bring moderate to occasionally heavy rains and thunderstorms over Central Visayas and the rest of Eastern Visayas Sea travel is risky over the seaboards of Luzon and Visayas. The public and the disaster risk reduction and management councils concerned are advised to take appropriate actions II. EFFECTS A. INCIDENTS MONITORED (TAB A) A total of twenty two (22) incidents were reported; fourteen (14) landslide incidents, six (6) floodings/flashflood incidents and two (2) marit ime incidents in Regions VIII, IX, X, XI, CARAGA and ARMM B. CASUALTIES (TAB B) A total of forty (40) persons were reported dead, sixty-five (65) are injured and five (5) are still missing in Regions IX, X, XI and CARAGA C. AFFECTED POPULATION (TAB C) A total of 123,444 families/587,115 persons were affected in 635 barangays in 90 municipalities in 15 provinces of Regions X, XI, CARAGA and ARMM Out of the total affected, 33,388 families / 161,808 persons were displaced and served inside 436 evacuation centers D. STATUS OF STRANDEES (as of 6:00 PM, 18 January 2014) ROLLING STRANDED PASSENGERS VESSELS MBCA’s CARGOES CGDCV CGS Cebu 175 14 20 04 CGS Dumaguete 63 05 03 02 CGDEV CGS Maasin 1,561 02 273 CGDBCL CGS Cam Sur 180 CGS Sorsogon 160 06 2 CGS Masbate 59 02 TOTAL 2,198 23 296 12 E. -

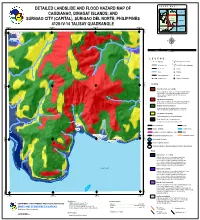

Detailed Landslide and Flood Hazard Map of Cagdianao

II NN DD EE XX MM AA PP :: DETAILED LANDSLIDE AND FLOOD HAZARD MAP OF 125°40'0"E 125°45'0"E 4120-IV-8 4120-IV-9 4120-IV-10 9°55'0"N CAGDIANAO, DINAGAT ISLANDS; AND 9°55'0"N SURIGAO CITY (Capital) SURIGAO CITY (CAPITAL), SURIGAO DEL NORTE, PHILIPPINES CAGDIANAO 4120-IV-13 4120-IV-14 4120-IV-15 4120-IV-14 TALISAY QUADRANGLE 125°39'0"E 125°40'0"E 125°41'0"E 125°42'0"E SURIGAO CITY (Capital) 4120-IV-19 4120-IV-20 4120-IV-18 9°50'0"N 9°50'0"N Purok I Mauswagon (Tigbao) Purok II Malipayon 125°40'0"E # (Tigbao) #n 9°54'0"N 9°54'0"N Purok III (Tigbao) #n Tigbao Elementary School (Tigbao) μ 0120.5 Kilometers LL E G E N D : Main road POBLACIONP! Barangay center location So. Magaling Secondary road (Poblacion)# Purok/Sitio location (Barangay) Track; trail n School River v® Hospital Municipal boundary G Church 80 Contour (meter) Proposed relocation site Landslide 9°53'0"N 9°53'0"N Very high landslide susceptibility Areas usually with steep to very steep slopes and underlain by weak materials. Recent landslides, escarpments and tension cracks are present. Human initiated effects could be an aggravating factor. High landslide susceptibility Areas usually with steep to very steep slopes and underlain by weak materials. Areas with numerous old/inactive landslides. Moderate landslide susceptibility Areas with moderately steep slopes. Soil creep and other indications of possible landslide occurrence are present. Low landslide susceptibility Gently sloping areas with no identified landslide. -

NAPOLEON WRASSE (Cheilinus Undulatus) “Mameng”

Danjugan Island, Philippines Photo by: Troy Mayne NAPOLEON WRASSE (Cheilinus undulatus) “Mameng” PHILIPPINE STATUS REPORT AND NATIONAL PLAN OF ACTION 2017-2022 SPECIAL ISSUE OF THE PHILIPPINE JOURNAL OF FISHERIES *** 1 Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources National Fisheries Research and Development Institute, Corporate 101 Mo. Ignacia Ave. South Triangle, Quezon City, Philippines, 1103 Telefax: (+632) 3725063 Email Address: [email protected] [email protected] ISBN: 978-971-8722-49-7 Philippine copyright © 2017 Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources National Fisheries Research and Development Institute Published by Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources National Fisheries Research and Development Institute All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of materials in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the sources is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited. Recommended entry: Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources - National Fisheries Research and Development Institute. 2017. Napoleon Wrasse (Cheilinus undulatus) “Mameng” Philippine Status Report and National Plan of Action 2017-2022, Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources - National Fisheries Research and Development Institute - Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH on behalf of the German Federal Ministry -

Detailed Landslide and Flood Hazard Map of Bunawan, Agusan Del Sur, Philippines 4117-Ii-5 Consuelo Quadrangle

II NN DD EE XX MM AA PP :: 125°55'0"E 126°0'0"E PAZ DETAILED LANDSLIDE AND FLOOD HAZARD MAP OF 4117-I-24 4117-I-25 4217-IV-21 8°15'0"N BUNAWAN, AGUSAN DEL SUR, PHILIPPINES 8°15'0"N PAZ RETO BUNAWAN 4117-II-5 4217-III-1 4117-II-5 CONSUELO QUADRANGLE 4117-II-4 125°57'0"E 125°58'0"E 125°59'0"E 126°0'0"E 4117-II-9 4117-II-10 4217-III-6 125°55'0"E 126°0'0"E 8°15'0"N 8°15'0"N Purok V (Consuelo)# μ n Consuelo Elementary School 0120.5 (Consuelo) Kilometers Purok IV (Consuelo)# LL E G E N D : Main road POBLACIONP! Barangay center location So. Magaling (Poblacion) Purok IIIA Secondary road # Purok/Sitio location (Barangay) (Consuelo)# Track; trail n School CONSUELOP River v® Hospital Municipal boundary G Church 80 Contour (meter) Proposed relocation site Purok I (Consuelo)# # Purok IIA Purok II (Consuelo)# (Consuelo) Landslide 8°14'0"N 8°14'0"N Very high landslide susceptibility Areas usually with steep to very steep slopes and underlain by weak materials. Recent landslides, escarpments and tension cracks are present. Human initiated effects could be an aggravating factor. High landslide susceptibility Areas usually with steep to very steep slopes and underlain by weak materials. Areas with numerous old/inactive landslides. Moderate landslide susceptibility Areas with moderately steep slopes. Soil creep and other indications of possible landslide occurrence are present. Purok VII (San Andres)# Low landslide susceptibility Gently sloping areas with no identified landslide. -

Sitrep No.07 Re Preparedness Measures for Tropical

SITREP NO. 07 TAB A Preparedness Measures and Effects of Tropical Depression "AMANG" AFFECTED POPULATION As of 23 January 2019, 8:00 AM TOTAL SERVED - CURRENT Region/Province/ AFFECTED No. of Evac Inside Evacuation Centers Outside Evacuation Centers (Inside + Outside) Mun/City Centers Brgys Families Persons Families Persons Families Persons Families Persons GRAND TOTAL 44 1,501 5,904 2 269 1,383 0 0 269 1,383 REGION XIII (CARAGA) 44 1,501 5,904 2 269 1,383 0 0 269 1,383 AGUSAN DEL NORTE 4 283 1,442 2 269 1,383 0 0 269 1,383 BUTUAN CITY 2 269 1,383 2 269 1,383 - - 269 1,383 JABONGA 2 14 59 0 0 0 - - 0 0 DINAGAT ISLANDS 9 166 477 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 BASILISA (RIZAL) 3 75 266 0 0 0 - - 0 0 SAN JOSE 6 91 211 0 0 0 - - 0 0 SURIGAO DEL NORTE 18 816 3,132 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 CLAVER 5 145 532 - - - - - 0 0 GENERAL LUNA 3 29 123 - - - - - 0 0 GIGAQUIT 4 89 313 0 0 0 - - 0 0 MALIMONO 2 251 1,073 - - - - - 0 0 SISON 3 134 490 - - - - - 0 0 SURIGAO CITY 1 168 601 0 0 0 - - 0 0 SURIGAO DEL SUR 13 236 853 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 BAROBO 2 34 131 0 0 0 - - 0 0 BAYABAS 3 62 201 0 0 0 - - 0 0 CARRASCAL 3 74 269 0 0 0 - - 0 0 LANUZA 4 45 188 - - - - - 0 0 TAGBINA 1 21 64 0 0 0 - - 0 0 Source: DSWD Dromic Report No.