Scratch Pad 54 October 2003 Scratch Pad 54

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Fantasy Convention 2003 Convention Fantasy World

ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED SERVICE ADDRESS [email protected] www.worldfantasy2003.org USA Annandale, VA 22003-1734 VA Annandale, 7113 Wayne Drive Wayne 7113 World Fantasy Convention 2003 Convention Fantasy World Progress Report Three The Washington Science Fiction Association presents: The 29th Annual World Fantasy Convention October 30th – November 2nd, 2003 Author Guest of Honor Brian Lumley Author Guest of Honor Jack Williamson Celebrating 75 years of Writing (Since Jack will not be able to attend, we shall be arranging a taped interview and other celebrations) Publisher Guest of Honor W. Paul Ganley Artist Guest of Honor Allen Koszowski Master of Ceremonies Douglas E. Winter Hyatt Regency Wachington on Capitol Hill © 2001 by Allen Koszowski Washington, DC USA 2003 World Fantasy Award Nominees _ _ _ _ _ _ Novel The Portrait of Mrs. Charbuque Jeffrey Ford (Morrow) Fitcher’s Brides Gregory Frost (Tor) The Facts of Life Graham Joyce (Gollancz) Ombria in Shadow Patricia A. McKillip (Ace) The Scar China Miéville (Macmillan U.K.; Del Rey) Novella Seven Wild Sisters Charles de Lint (Subterranean Press) A Year in the Linear City Paul Di Filippo (PS Publishing) c/o Jerry Crutcher Coraline Neil Gaiman (HarperCollins) Box 1096 Post Office “The Least Trumps” Elizabeth Hand (Conjunctions 39: The New Wave Fabulists) [email protected] “The Library” Zoran Zivkovic (Leviathan 3) Membership Registration Rockville, MD 20849-1096 USA Short Story “Creation” Jeffrey Ford (F&SF 5/02) “The Weight of Words” Jeffrey Ford (Leviathan 3) “October in the Chair” Neil Gaiman (Conjunctions 39: The New Wave Fabulists) “Little Dead Girl Singing” Stephen Gallagher (Weird Tales Spring 2002) “The Essayist in the Wilderness” William Browning Spencer (F&SF 5/02) Anthology The Green Man: Tales from the Mythic Forest Ellen Datlow & Terri Windling, Editors (Viking) The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror: Fifteenth Annual Collection Ellen Datlow &Terri Windling, Eds. -

Progress Report 3 APRIL 2020

Progress report 3 APRIL 2020 1 Table of Contents Experience Chair — Norman Cates Vice Chair: Experience — Lynelle Howell Chairs’ Message ____________________________________________2 Business Chair — Kelly Buehler Vice Chair: Business — David Gallaher Virtual Worldcon ___________________________________________4 Memberships _______________________________________________5 Crew Services Division Head: Programme Participants ____________________________________6 Events Division Head: Mel Duncan Exhibits Division Head: Spike Changing Travel and Accommodation ______________________7 Facilities Division Head: Ben Yalow Questions and Answers _____________________________________7 Finance Division Head: Andrew A Adams Information Technology Division Head: Grant Preston Kia Ora! ____________________________________________________11 Member Services Division Head: PRK Help Wanted _______________________________________________13 Operational Services Division Heads: Rick Kovalcik & Sharon Sbarsky Platform Services Division Heads: Patty Wells & Randall Shepherd Site Selection and Hugo Ballots ____________________________14 Programme Division Head: Jannie Shea Membership List ___________________________________________16 Promotions Division Head: Nikky Winchester Publications Division Head: Darusha Wehm Registration Division Head: Lorain Clark Tech Division Head: John Maizels WSFS Division Head: Colette Fozard Cover photo by: Daniel Rood “World Science Fiction Society”, “WSFS”, “World Science Fiction Convention”, “Worldcon”, “NASFIC” “Hugo Award”, -

Uneven Development in Charles De Lint's Urban Fantasy Matthew

Fantasy as a Peripheral Modernism: Uneven Development in Charles de Lint’s Urban Fantasy Matthew Rettino Department of English McGill University, Montreal April 2016 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Matthew Rettino 2016 Rettino 2 Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction: Fantasy as a Peripheral Modernism .......................................................................... 6 Urban Fantasy in Context ......................................................................................................... 13 Outline of the Present Work ..................................................................................................... 17 Chapter 1: Fantasy as a Modernism of the Capitalist World-System ........................................... 22 Magic Realist Aesthetics and World Literature ........................................................................ 24 The Emergence of Fantasy as Modernism ................................................................................ 29 Chapter 2: Uneven Development in Canada: Multiculturalism and Colonialism in Moonheart . 46 Plot of Moonheart .................................................................................................................... -

SF Commentary 106

SF Commentary 106 May 2021 80 pages A Tribute to Yvonne Rousseau (1945–2021) Bruce Gillespie with help from Vida Weiss, Elaine Cochrane, and Dave Langford plus Yvonne’s own bibliography and the story of how she met everybody Perry Middlemiss The Hugo Awards of 1961 Andrew Darlington Early John Brunner Jennifer Bryce’s Ten best novels of 2020 Tony Thomas and Jennifer Bryce The Booker Awards of 2020 Plus letters and comments from 40 friends Elaine Cochrane: ‘Yvonne Rousseau, 1987’. SSFF CCOOMMMMEENNTTAARRYY 110066 May 2021 80 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 106, May 2021, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3088, Australia. Email: [email protected]. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. .PDF FILE FROM EFANZINES.COM. For both print (portrait) and landscape (widescreen) editions, go to https://efanzines.com/SFC/index.html FRONT COVER: Elaine Cochrane: Photo of Yvonne Rousseau, at one of those picnics that Roger Weddall arranged in the Botanical Gardens, held in 1987 or thereabouts. BACK COVER: Jeanette Gillespie: ‘Back Window Bright Day’. PHOTOGRAPHS: Jenny Blackford (p. 3); Sally Yeoland (p. 4); John Foyster (p. 8); Helena Binns (pp. 8, 10); Jane Tisell (p. 9); Andrew Porter (p. 25); P. Clement via Wikipedia (p. 46); Leck Keller-Krawczyk (p. 51); Joy Window (p. 76); Daniel Farmer, ABC News (p. 79). ILLUSTRATION: Denny Marshall (p. 67). 3 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS, PART 1 34 TONY THOMAS TO MY FRIENDS, PART 1 THE BOOKER PRIZE 2020 READING EXPERIENCE 3, 7 41 JENNIFER BRYCE A TRIBUTE TO YVONNNE THE 2020 BOOKER PRIZE -

Wins DITMAR and ATHELING AWARDS Harlan Ellison Wins Fans at Syncon *83 BRUCE GILLESPIE to RECEIVE WORLD SF AWARD

Terry Dowling Wins DITMAR and ATHELING AWARDS Harlan Ellison Wins Fans At Syncon *83 BRUCE GILLESPIE TO RECEIVE WORLD SF AWARD TOE AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS - THE DITMARS, were presented at the 22nd Australian National Science Fiction Convention -SYNCON '83, which was held at the Shore Motel, Artarmon, Sydney, June 10-13. The highlight of this well organised convention, one of the best all round sf cons we have seen in Australia, was the showman like performance of the Guest of Honour, HARLAN ELLISON. He had all the fans practically eating out of his hands, with the colourful and dramatic style of his speech making, readings and conversation. Besides TERRY DOWLING, the inevitable two awards went to MARC ORTLIEB again and ROBIN JOHNSON received the Special Award for Services to Australian Science Fiction. The full list of winners is as follows: BEST INTERNATIONAL SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY RIDDLEY WALKER by Russell Hoban (Jonathan Cape / Pan J BEST AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY "The Man Who Walked Away Behind the Eyes" by Terry Dowling (OMEGA May/June '83 ) BEST AUSTRALIAN FANZINE BEST AUSTRALIAN FAN WRITER Q 36 Edited by Marc Ortlieb Marc Ortlieb BEST AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY ARTIST BRUCE GILLESPIE & ELAINE COCHRANE (Photo John Litchen) Marilyn Pride Melbourne fan and publisher BRUCE GILLESPIE has been awarded the World SF organisation's BEST AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY CARTOONIST "Harrison Award" for Increasing the Status John Packer of Science Fiction Internationally. Two other recipients of this award were Sam Lundwell BEST AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY EDITOR and Krsto Mazuranic. -

Australian Science Fiction: in Search of the 'Feel' Dorotta Guttfeld

65 Australian Science Fiction: in Search of the ‘Feel’ Dorotta Guttfeld, University of Torun, Poland This is our Golden Age – argued Stephen Higgins in his editorial of the 11/1997 issue of Aurealis, Australia’s longest-running magazine devoted to science fiction and fantasy. The magazine’s founder and editor, Higgins optimistically pointed to unprecedented interest in science fiction among Australian publishers. The claim about a “Golden Age” echoed a statement made by Harlan Ellison during a panel discussion “The Australian Renaissance” in Sydney the year before (Ellison 1998, Dann 2000)64. International mechanisms for selection and promotion in this genre seemed to compare favorably with the situation of Australian fiction in general. The Vend-A-Nation project (1998) was to encourage authors to write science fiction stories set in the Republic of Australia, and 1999 was to see the publication of several scholarly studies of Australian science fiction, including Russell Blackford’s and Sean McMullen’s Strange Constellations. Many of these publications were timed to coincide with the 1999 ‘Worldcon’, the most prestigious of all fan conventions, which had been awarded to Melbourne. The ‘Worldcon’ was thus about to become the third ‘Aussiecon’ in history, accessible for the vibrant fan community of Australia, and thus sure to provide even more impetus for the genres’ health. And yet, in the 19/2007 issue of Aurealis, ten years after his announcement of the Golden Age, Stephen Higgins seems to be using a different tone: Rather than talk of a new Golden Age of Australian SF (and there have been plenty of those) I prefer to think of the Australian SF scene as simply continuing to evolve. -

SF Commentarycommentary 80A80A

SFSF CommentaryCommentary 80A80A August 2010 SSCCAANNNNEERRSS 11999900––22000022 Doug Barbour Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Bruce Gillespie Paul Ewins Alan Stewart SF Commentary 80A August 2010 118 pages Scanners 1990–2002 Edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia as a supplement to SF Commentary 80, The 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 1, also published in August 2010. Email: [email protected] Available only as a PDF from Bill Burns’s site eFanzines.com. Download from http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC80A.pdf This is an orphan issue, comprising the four ‘Scanners’ columns that were not included in SF Commentary 77, then had to be deleted at the last moment from each of SFCs 78 and 79. Interested readers can find the fifth ‘Scanners’ column, by Colin Steele, in SF Commentary 77 (also downloadable from eFanzines.com). Colin Steele’s column returns in SF Commentary 81. This is the only issue of SF Commentary that will not also be published in a print edition. Those who want print copies of SF Commentary Nos 80, 81 and 82 (the combined 40th Anniversary Edition), should send money ($50, by cheque from Australia or by folding money from overseas), traded fanzines, letters of comment or written or artistic contributions. Thanks to Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) for providing the cover at short notice, as well as his explanatory notes. 2 CONTENTS 5 Ditmar: Dick Jenssen: ‘Alien’: the cover graphic Scanners Books written or edited by the following authors are reviewed by: 7 Bruce Gillespie David Lake :: Macdonald Daly :: Stephen Baxter :: Ian McDonald :: A. -

9 Fantastical Worlds and Futures at the World's

FANTASTICAL WORLDS AND FUTURES AT THE WORLD'S EDGE: A HISTORY OF NEW ZEALAND SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY by Simon Litten and Sean McMullen CHAPTER 2: SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY REBORN With the late 1950s and 1960s came satellites passing overhead among the stars, the threat of nuclear annihilation, the growing presence of computers in science, commerce and industry, and space travel for humans. Overall the public was more aware of technology than ever before. Television reached New Zealand in 1960, and on television were such series as Men in Space, Star Trek, The Twilight Zone, The Outer Limits and Out of the Unknown. In the cinemas, the films Doctor Strangelove and On the Beach made the public aware that destroying the world to save it from communism might not be a terribly sensible idea. Science and science fiction were suddenly highly visible and very fashionable, even in remote New Zealand. After over half a century of absence, science fiction novels by New Zealanders began to again be published in book form, now marketed as science fiction, making them a lot easier to track down. The first of these was Adrienne Geddes's novel of alien invasion, The Rim of Eternity (Collins Brothers and Co, 1964) published in Auckland. Geddes may well be New Zealand's first female science fiction author, but little is known about her, and this appears to be her only work. Michael Joseph was the author of The Hole in the Zero (Avon Books, 1967) and The Time of Achamoth (William Collins, 1977). The author was born in Britain but completed his schooling in New Zealand, and went on to become a professor of English. -

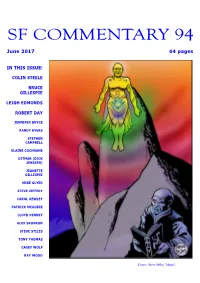

Sf Commentary 94

SF COMMENTARY 94 June 2017 64 pages IN THIS ISSUE: COLIN STEELE BRUCE GILLESPIE LEIGH EDMONDS ROBERT DAY JENNIFER BRYCE RANDY BYERS STEPHEN CAMPBELL ELAINE COCHRANE DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) JEANETTE GILLESPIE MIKE GLYER STEVE JEFFERY CAROL KEWLEY PATRICK MCGUIRE LLOYD PENNEY ALEX SKOVRON STEVE STILES TONY THOMAS CASEY WOLF RAY WOOD Cover: Steve Stiles: ‘Mages’. SF COMMENTARY 94 June 2017 64 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 94, June 2017, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3088, Australia. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. AVAILABLE ONLY FROM EFANZINES.COM: Portrait edition (print page equivalent) at http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC94P.PDF or Landscape edition (widescreen): at http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC94L.PDF or from my NEW email address: [email protected] FRONT COVER: Steve Stiles: ‘Mage’. :: BACK COVER: (and p. 3): Randy Byers: ‘Cannon Beach’. Artwork: Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) (pp. 24, 28, 29); Stephen Campbell (p. 24); Elaine Cochrane (p. 26); Taral (p. 49); Casey Wolf (p. 60); Claude Perrault (p. 62). PHOTOGRAPHS: Jeanette Gillespie (pp. 24, 27); LynC (p. 24); Ian Roberts (p. 27); Dick Jenssen (p. 29); Leigh Edmonds (pp. 21, 38–9); Ray Wood (pp. 51–2); Casey Wolf (p. 62). 4 THE FIELD Colin Steele 30 LEIGH EDMONDS’ ‘HISTORY OF 4 End of an era at The Canberra Times AUSTRALIAN FANDOM’ PROJECT 6 Books about SF and fantasy 35 ON HOT PURSUIT OF FANZINE 9 Australian young adult fiction TREASURE: THE PERTH TRIP 9 British science fiction Leigh Edmonds 13 British alternative world SF 14 British fantasy, dark fantasy, horror -

July 2015 NASFA Shuttle

Te Shutle July 2015 The Next NASFA Meeting is 6:30P Saturday 25 July 2015 at the Regular Location Concom: 3P Saturday 25 July 2015, at the Church past by the time this issue goes to bed) was 6P on Thursday 16 d Oyez, Oyez d July 2015 at Sam and Judy Smith’s house. ! The second July Con†Stellation XXXIII Concom Meeting The next NASFA Meeting will be 6:30P Saturday 25 July will be at 3P on 25 July 2015—the same day as this month’s 2015. NOTE that this is the 4th Saturday—a delay of 1 week club meeting. It will be held at the same place as the club meet- from normal—to avoid a conflict with Con Kasterborous. The ing, Willowbrook Baptist Church. There will be a dinner break meeting will be at the regular location—the Madison campus between the Concom Meeting and the NASFA Business Meet- of Willowbrook Baptist Church (old Wilson Lumber Company ing. building) at 7105 Highway 72W (aka University Drive). We are working on a full set of tentative dates/places for Please see the map at right if you need help finding it. concom meetings for the rest of this year. Please stay tuned to PLEASE NOTE that per a vote at the October 2014 meet- ing, the start of the Business Meeting has changed from 6P to 6:30P. Programs are still scheduled to start at 7P. JULY PROGRAM Road Jeff Kroger The July program will be presented by OLLI—the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at UAH <www.uah.edu/pcs/olli>. -

Thyme #48 the Regular-As-Clockwork, Monthly Australian Newszine with All the News That Fits (And Seme That Doesn’T)

The Bulletin, 17th July, 1971 passions under tighter control. The THE SF WORLD OF blurb on the back of one of the paper BEMS, SERCONS AND BNFS backs reads: “To the world at large, REMEMBER science fiction? A few Doc Savage is a strange, mysterious years ago it almost died of rigor mortis. figure of glistening bronze skin and Science, regetfably, had overtaken SF, golden eyes. To his amazing Everything SF had been writing about co-adventurers — the five greatest for years, walks in space, moon land brains ever assembled in one group — ings and such, was really happening. he is a man of superhuman strength There wasn’t much point in writing and protean genius whose life is dedi-i about it any more. cated to the destruction of evil-doers. To his fani.hc is the greatest adven- Suddenly SF is going through per ^|prer‘of all time.” haps its greatest boom ever. Melbourne ’ Eee'Harding, one ©(-Australia’s most has had two SF conventions this year — successful SF writers, was there. One one in January and another at Easter. wondered, apart from nostalgia, what Indeed local fans arc feeling so potent j had caused the revival. “A number of they are making a bid for the 1975 things,” he said, “books like James Worldcon, that is the world.convention, I Bond have helped. And television — the Olympic Games of SF, and Sercons ’The.Man From Uncle,’ ‘The Avengers' (Serious Constructive Fans) and and various SF series. Apart from any- BNFs (Big Name Fans) will fly in by '■ thing else the world is in such a mess, the plane load from Britain and the SF and fantasy are a means of escape.” U.S. -

SF Commentary 99

SSFF CCoommmmeennttaarryy 9999 5500tthh AAnnnniivveerrssaarryy EEddiittiioonn,, PPaarrtt 22 113300 ppaaggeess JJuullyy 22001199 Cover: Randy Byers: ‘Morning Glory’. Photograph S F Commentary 99 50th Anniversary Edition * Part 2 July 2019 130 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 99, 50th ANNIVERSARY EDITION, PART 2, July 2019, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3088, Australia. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. Preferred means of distribution .PDF file from eFanzines.com: http://efanzines.com or from my email address: [email protected]. FRONT COVER: Randy Byers: ‘Morning Glory’: photograph. BACK COVER: Ditmar (Dick Jenssen): ‘Dancing Almond Bread’. DJ Graphic. ARTWORK: Sheryl Birkhead (pp. 17–20); John Bangsund (pp. 84–6); John Foyster (pp. 90–2); Denny Marshall (p.112). PHOTOGRAPHS: Cat Sparks (p. 4); Randy Byers (p. 6); Merv Binns (p. 8); Elaine Cochrane (pp. 13–15); Laurraine Tutihasi (p. 18); Sheryl Birkhead (p. 43); Giampaolo Cossato (p. 57); George Turner (p. 87); John Foyster (pp. 98–104). 2 Contents 4 THE GLITTERING PRIZES Patrick McGuire 5 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS 60 FEATURE LETTERS Bruce Gillespie 60 Gerald Murnane: Breakthrough at the age of 79 64 Mars and Beyond: Patrick McGuire, John Litchen, 6 TRIBUTES Greg Benford 6 Gillian Polack pays tribute to Vonda McIntyre 69 Always Coming Home: Yvonne Rousseau (and Ursula Le Guin) 7 Bruce Gillespie and Yvonne Rousseau pay tribute to Gene Wolfe: 71 Patrick McGuire: Polite and detailed disagreements 9 Peace, reviewed by Yvonne Rousseau 11 Ron Drummond’s