Ivan and His Doubles: the Failure of Intellect in the Brothers Karamazov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebellion Brothers Karamazov

Book V, Chapter IV. Rebellion from The Brothers Karamazov (Fyodor Dostoyevsky) Trans: Constance Garnett Project Gutenber Edition “I must make you one confession,” Ivan began. “I could never understand how one can love one's neighbors. It's just one's neighbors, to my mind, that one can't love, though one might love those at a distance. I once read somewhere of John the Merciful, a saint, that when a hungry, frozen beggar came to him, he took him into his bed, held him in his arms, and began breathing into his mouth, which was putrid and loathsome from some awful disease. I am convinced that he did that from ‘self-laceration,’ from the self-laceration of falsity, for the sake of the charity imposed by duty, as a penance laid on him. For any one to love a man, he must be hidden, for as soon as he shows his face, love is gone.” “Father Zossima has talked of that more than once,” observed Alyosha; “he, too, said that the face of a man often hinders many people not practiced in love, from loving him. But yet there's a great deal of love in mankind, and almost Christ-like love. I know that myself, Ivan.” “Well, I know nothing of it so far, and can't understand it, and the innumerable mass of mankind are with me there. The question is, whether that's due to men's bad qualities or whether it's inherent in their nature. To my thinking, Christ-like love for men is a miracle impossible on earth. -

Jews on Trial: the Papal Inquisition in Modena

1 Jews, Papal Inquisitors and the Estense dukes In 1598, the year that Duke Cesare d’Este (1562–1628) lost Ferrara to Papal forces and moved the capital of his duchy to Modena, the Papal Inquisition in Modena was elevated from vicariate to full Inquisitorial status. Despite initial clashes with the Duke, the Inquisition began to prosecute not only heretics and blasphemers, but also professing Jews. Such a policy towards infidels by an organization appointed to enquire into heresy (inquisitio haereticae pravitatis) was unusual. In order to understand this process this chapter studies the political situation in Modena, the socio-religious predicament of Modenese Jews, how the Roman Inquisition in Modena was established despite ducal restrictions and finally the steps taken by the Holy Office to gain jurisdiction over professing Jews. It argues that in Modena, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Holy Office, directly empowered by popes to try Jews who violated canons, was taking unprecedented judicial actions against them. Modena, a small city on the south side of the Po Valley, seventy miles west of Ferrara in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy, originated as the Roman town of Mutina, but after centuries of destruction and renewal it evolved as a market town and as a busy commercial centre of a fertile countryside. It was built around a Romanesque cathedral and the Ghirlandina tower, intersected by canals and cut through by the Via Aemilia, the ancient Roman highway from Piacenza to Rimini. It was part of the duchy ruled by the Este family, who origi- nated in Este, to the south of the Euganean hills, and the territories it ruled at their greatest extent stretched from the Adriatic coast across the Po Valley and up into the Apennines beyond Modena and Reggio, as well as north of the Po into the Polesine region. -

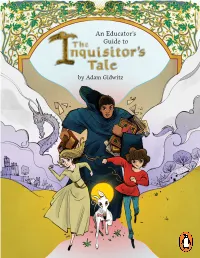

An Educator's Guide To

An Educator’s Guide to by Adam Gidwitz Dear Educator, I’m at the Holy Crossroads Inn, a day’s walk north of Paris. Outside, the sky is dark, and getting darker… It’s the perfect night for a story. Critically acclaimed Adam Gidwitz’s new novel has “as much to say about the present as it does the past.” (— Publishers Weekly). Themes of social justice, tolerance and empathy, and understanding differences, especially as they relate to personal beliefs and religion, run through- out his expertly told tale. The story, told from multiple narrator’s points of view, is evocative of The Canterbury Tales—richly researched and action packed. Ripe for 4th-6th grade learners, it could be read aloud or assigned for at-home or in-school reading. The following pages will guide you through teaching the book. Broken into sections and with suggested links and outside source material to reference, it will hopefully be the starting point for you to incorporate this book into the fabric of your classroom. We are thrilled to introduce you to a new book by Adam, as you have always been great champions of his books. Thank you for your continued support of our books and our brand. Penguin School & Library About the Author: Adam Gidwitz taught in Brooklyn for eight years. Now, he writes full- time—which means he writes a couple of hours a day, and lies on the couch staring at the ceiling the rest of the time. As is the case with all of this books, everything in them not only happened in the real fairy tales, it also happened to him. -

Dostoevsky's Ideal

Student Publications Student Scholarship Fall 2015 Dostoevsky’s Ideal Man Paul A. Eppler Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Philosophy Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Eppler, Paul A., "Dostoevsky’s Ideal Man" (2015). Student Publications. 395. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/395 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 395 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dostoevsky’s Ideal Man Abstract This paper aimed to provide a comprehensive examination of the "ideal" Dostoevsky human being. Through comparison of various characters and concepts found in his texts, a kenotic individual, one who is undifferentiated in their love for all of God's creation, was found to be the ultimate to which Dostoevsky believed man could ascend. Keywords Dostoevsky, Christianity, Kenoticism Disciplines Philosophy Comments This paper was written for Professor Vernon Cisney's course, PHIL 368: Reading- Dostoevsky, Fall 2015. This student research paper is available at The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ student_scholarship/395 Dostoevsky’s Ideal Man Paul Eppler Professor Vernon Cisney Reading Dostoevsky I affirm that I have upheld the highest principles of honesty and integrity in my academic work and have not witnessed a violation of the Honor Code. -

Christ and the Temptations of Modernity

9 Christ and the Temptations of Modernity David Hawkin One of the trUly great short stories of Western literatUre is “The Grand InqUisitor” which is foUnd in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel, The Brothers Karamazov . In the novel the story of the Grand InqUisitor is told by one of the brothers, Ivan, to another brother, Alyosha. It is set in the sixteenth centUry in Seville in Spain, at the height of the InqUisition. Ivan, the storyteller, tries to envisage what woUld have happened had Christ reappeared at this time. Ivan says, ‘He came Unobserved and moved aboUt silently bUt, strangely enoUgh, those who saw him recognized him at once.’ 1 Having recognized him, a woman in the crowd, in the process of bUrying her dead daUghter, beseeches Christ to raise her daUghter from the dead. Christ does so. It is at this point that the Grand InqUisitor, a wizened 90 year old, appears. He sees Christ raise the girl from the dead. At once he orders Christ to be arrested and imprisoned. Ivan continUes— The Grand InqUisitor’s power is so great and the people are so sUbmissive and tremblingly obedient to him that they immediately open Up a passage for the gUards. A death like silence descends Upon [the gathered crowd] and in that silence the gUards lay hands on [Christ] and lead him away. Then everyone in the crowd, to a man, prostrates himself before the Grand InqUisitor. The old man blesses them in silence and passes on. 2 At night, the old man visits Christ in prison. He knows who Christ is, bUt he does not fall down and worship him. -

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY the Roman Inquisition and the Crypto

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY The Roman Inquisition and the Crypto-Jews of Spanish Naples, 1569-1582 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of History By Peter Akawie Mazur EVANSTON, ILLINOIS June 2008 2 ABSTRACT The Roman Inquisition and the Crypto-Jews of Spanish Naples, 1569-1582 Peter Akawie Mazur Between 1569 and 1582, the inquisitorial court of the Cardinal Archbishop of Naples undertook a series of trials against a powerful and wealthy group of Spanish immigrants in Naples for judaizing, the practice of Jewish rituals. The immense scale of this campaign and the many complications that resulted render it an exception in comparison to the rest of the judicial activity of the Roman Inquisition during this period. In Naples, judges employed some of the most violent and arbitrary procedures during the very years in which the Roman Inquisition was being remodeled into a more precise judicial system and exchanging the heavy handed methods used to eradicate Protestantism from Italy for more subtle techniques of control. The history of the Neapolitan campaign sheds new light on the history of the Roman Inquisition during the period of its greatest influence over Italian life. Though the tribunal took a place among the premier judicial institutions operating in sixteenth century Europe for its ability to dispense disinterested and objective justice, the chaotic Neapolitan campaign shows that not even a tribunal bearing all of the hallmarks of a modern judicial system-- a professionalized corps of officials, a standardized code of practice, a centralized structure of command, and attention to the rights of defendants-- could remain immune to the strong privatizing tendencies that undermined its ideals. -

By Fyodor Dostoevsky

“The Problem of Evil ” by Fyodor Dostoevsky Dostoevsky, (detail) portrait by Vasily Perov, The State Tretyakov Gallery About the author.. The novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881) spent four years in a Siberian prison and four more years in the army as punish- ment for his role in a clandestine Utopian-socialist discussion group. He became scornful of the rise of humanistic science in the West and chron- icled its threat to human freedom. Dostoevsky’s writings challenged the notion of the essential rationality of human beings and anticipated many ideas in existential psychoanalysis. For Dostoevsky, the essence of being human is freedom. About the work. In the The Brothers Karamazov,1 Dostoevsky reveals deep psychological insight into the nature of human morality. In this, his greatest work, he expresses the destructive aspects of human freedom which can only be bound by God. In Chapter 4 of that work, the death of an innocent child is seen to be an inescapable objection to God’s good- ness. In this chapter Alyosha is the religious foil to Ivan, his intellectual older brother. 1. Fyodor Dostoevsky. “Rebellion” in the The Brothers Karamazov (1879). Trans. by Constance Garnett. 1 “The Problem of Evil ” by Fyodor Dostoevsky From the reading. “But then there is the children, and what am I to do about them? That’s a question I can’t answer.” Ideas of Interest from The Brothers Karamazov 1. Why does Ivan think that children are innocent and adults are not? Why does he think we can love children when they are close, but we can only love our neighbor abstractly? 2. -

Spanish Persecution of the 15Th-17Th Centuries: a Study of Discrimination Against Witches at the Local and State Levels Laura Ledray Hamline University

Hamline University DigitalCommons@Hamline Departmental Honors Projects College of Liberal Arts Spring 2016 Spanish Persecution of the 15th-17th Centuries: A Study of Discrimination Against Witches at the Local and State Levels Laura Ledray Hamline University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hamline.edu/dhp Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Ledray, Laura, "Spanish Persecution of the 15th-17th Centuries: A Study of Discrimination Against Witches at the Local and State Levels" (2016). Departmental Honors Projects. 51. https://digitalcommons.hamline.edu/dhp/51 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts at DigitalCommons@Hamline. It has been accepted for inclusion in Departmental Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Hamline. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 1 Spanish Persecution of the 15th-17th Centuries: A Study of Discrimination Against Witches at the Local and State Levels Laura Ledray An Honors Thesis Submitted for partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors in History from Hamline University 4/24/2016 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction_________________________________________________________________________________________3 Historiography______________________________________________________________________________________8 Origins of the Spanish Inquisition_______________________________________________________________15 Identifying -

Reconquista and Spanish Inquisition

Name __________________________________________ Date ___________ Class _______ Period _____ The Reconquista and the Spanish Inquisition by Jessica Whittemore (education-portal.com) Directions: Read the article and answer the questions in full sentences. Muslim Control Of Spain The Reconquista and especially the Inquisition encompass one of the darkest times in Spanish history. It was a time when faith, greed and politics combined to bring about the deaths of many. Let's start with the Spanish Reconquista. In simpler terms, the Reconquista was the attempt by Christian Spain to expel all Muslims from the Iberian Peninsula. In the 8th century, Spain was not one united nation but instead a group of kingdoms. In the early 8th century, these kingdoms of Spain were invaded by Muslim forces from North Africa. Within a few years of this invasion, most of Spain was under Muslim control. In fact, the Muslims renamed the Spanish kingdoms Al- Andalus or Andalusia, but for our purposes, we're going to stick with Spain. Since the Muslims were an advanced society, Spain prospered. The Muslims were also very tolerant of other religions, allowing Muslims, Christians and Jews to basically take up the same space. However, Muslim political leaders were very suspicious of one another, which led to disunity among the many kingdoms. This disunity opened up the doors for Christian rule to seep in, and while the Muslims kept firm control of the southern kingdoms of Granada, Christian power began taking hold in the northern kingdoms of Aragon, Castile and Navarre. By the end of the 13th century, only Granada remained under Muslim control. -

The Grand Inquisitor,” Is Told by Ivan Karamazov to His Younger Brother Alyosha

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881), author of such works as Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, and The Possessed, is considered by many to be one of the world’s greatest writers, and the novel The Brothers Karamazov is universally recognized to be one of genuine masterpieces of world literature. Within this novel the story, “The Grand Inquisitor,” is told by Ivan Karamazov to his younger brother Alyosha. The two brothers had just been discussing the problem of evil—the classic problem of Christian theology: if God is really all powerful, all knowing, and truly loving, then why does evil exist? If God could not have prevented evil, then he is not all powerful. If evil somehow escapes his awareness, then he is not all knowing. If he knew, and could do something about it, but chose not to, then how can he be considered a loving God? One solution to this problem is to claim that evil does not really exist, that if we were to see the world Portrait of Fyodor Dostoyevsky, 1872 from God’s perspective, from the perspective of eternity, then everything comes out well in the end. Another response is to claim that it really isn’t God’s fault at all, it is ours. God gave us free-will and evil is the result of our misuse of that gift. Ivan will have none of these arguments. He brings up the particularly troubling case of the suffering of innocent children—how can they be blamed and punished if they are innocent? Ivan cannot accept that the suffering of an innocent child will be justified in the end. -

Trial and Error the Malleability of Truth in the Conviction of Dmitri Karamazov

Trial and Error The Malleability of Truth in the Conviction of Dmitri Karamazov monica coscia Fyodor dostoevsky’s timeless novel, The BroThers Karamazov, explores the eternal question oF whether judicial systems can actually attain justice and truth. set in nineteenth-century russia, the novel tells the story oF Fyodor pavlovich and his sons: the rationalist ivan, the religious alyosha, the sensualist dmitri, and the ille- gitimate smerdyakov. the sudden murder oF Fyodor spawns Familial and societal dis- cord, and dmitri is charged with patricide. the novel culminates in a thrilling court- room drama that captures the attention oF the karamazov Family’s entire community. this discourse views dostoevsky’s jury trial in The BroThers Karamazov not only as the trial oF dmitri karamazov, but also as a trial oF russian culture, pitting tradi- tionalism against modernity. this paper assesses how russia’s dualistic culture sets the stage For dostoevsky to invent attorneys, witnesses, judges, and spectators who illustrate the various Facets oF late-nineteenth-century russian society at its pivotal crossroads. the article ultimately explains how dostoevsky’s thrilling legal battle reveals his doubt that the russian courts, or any arbitrarily established legal sys- tem, could ever achieve true justice. During the latter part of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s life, Russia Russia and in Europe.”4 Accordingly, Dostoevsky read in- lays “between a past which has not quite ended and a fu- numerable types of literature from all regions of the cul- ture which has not quite begun.”1 The beauty of Dosto- tural spectrum-novels, periodicals, Christian literature, evsky’s literature lies in its depiction of both sides of this classic Western works, psychological treatises, and tradi- turning point in Russian history: on one hand, he writes of tional Russian literature.5 Dostoevsky learned about West- Russia’s rich, unique national identity and traditional val- ern liberalism and idealism and contrasted it with Russian ues. -

“Viper Will Eat Viper”: Dostoevsky, Darwin, and the Possibility of Brotherhood

III “Viper will eat viper”: Dostoevsky, Darwin, and the Possibility of Brotherhood Anna A. Berman As Darwinian thought took root across Europe and Russia in the 1860s after the publication of On the Origin of Species (1859), intellectuals wrestled with the troubling implications the “struggle for existence” held for human harmony and love. How could people be expected to “love their neighbors” if that love ran counter to science? Was that love even commendable if it counteracted the perfection of the human race through the process of natural selection? And if Darwinian struggle was supposed to be most intense among those who were closest and had the most shared resources to compete for, what hope did this hold for the family? Darwin’s Russian contemporaries were particularly averse the idea that members of the same species were in competition. As Daniel Todes, James Rogers, and Alexander Vucinich have argued, Russian thinkers attempted to reject the Malthusian side of Darwin’s theory.1 Situated in the harsh, vast expanses of Russia, rather than on the crowded, verdant British Isles, they 1 Daniel Todes, Darwin without Malthus: The Struggle for Existence in Russian Evolutionary Thought (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989); James Allen Rogers, “The Russian Populists’ Response to Darwin,” Slavic Review 22, no. 3 (1963): 456–68; Alexander Vucinich, Darwin in Russian Thought (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988). 84 Anna A. Berman argued that of the three struggles Darwin included under the umbrella of “struggle for existence”—(1)