The Evolution of Birkat Al-Fil (From the Fatimids to the Twentieth Century)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thermal Assessment of a Novel Combine Evaporative Cooling Wind Catcher

energies Article Thermal Assessment of a Novel Combine Evaporative Cooling Wind Catcher Azam Noroozi * and Yannis S. Veneris School of Architecture, National Technical University of Athens, Section III, 42 Patission Av., 10682 Athens, Greece; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-210-772-3885 (ext. 3567) Received: 5 January 2018; Accepted: 13 February 2018; Published: 15 February 2018 Abstract: Wind catchers are one of the oldest cooling systems that are employed to provide sufficient natural ventilation in buildings. In this study, a laboratory scale wind catcher was equipped with a combined evaporative system. The designed assembly was comprised of a one-sided opening with an adjustable wetted pad unit and a wetted blades section. Theoretical analysis of the wind catcher was carried out and a set of experiments were organized to validate the results of the obtained models. The effect of wind speed, wind catcher height, and mode of the opening unit (open or closed) was investigated on temperature drop and velocity of the moving air through the wind catcher as well as provided sensible cooling load. The results showed that under windy conditions, inside air velocity was slightly higher when the pad was open. Vice versa, when the wind speed was zero, the closed pad resulted in an enhancement in air velocity inside the wind catcher. At wind catcher heights of 2.5 and 3.5 m and wind speeds of lower than 3 m/s, cooling loads have been approximately doubled by applying the closed-pad mode. Keywords: wind catcher; cooling system; experimental validation; thermal modeling 1. -

Prophets of the Quran: an Introduction (Part 1 of 2)

Prophets of the Quran: An Introduction (part 1 of 2) Description: Belief in the prophets of God is a central part of Muslim faith. Part 1 will introduce all the prophets before Prophet Muhammad, may the mercy and blessings of God be upon him, mentioned in the Muslim scripture from Adam to Abraham and his two sons. By Imam Mufti (© 2013 IslamReligion.com) Published on 22 Apr 2013 - Last modified on 25 Jun 2019 Category: Articles >Beliefs of Islam > Stories of the Prophets The Quran mentions twenty five prophets, most of whom are mentioned in the Bible as well. Who were these prophets? Where did they live? Who were they sent to? What are their names in the Quran and the Bible? And what are some of the miracles they performed? We will answer these simple questions. Before we begin, we must understand two matters: a. In Arabic two different words are used, Nabi and Rasool. A Nabi is a prophet and a Rasool is a messenger or an apostle. The two words are close in meaning for our purpose. b. There are four men mentioned in the Quran about whom Muslim scholars are uncertain whether they were prophets or not: Dhul-Qarnain (18:83), Luqman (Chapter 31), Uzair (9:30), and Tubba (44:37, 50:14). 1. Aadam or Adam is the first prophet in Islam. He is also the first human being according to traditional Islamic belief. Adam is mentioned in 25 verses and 25 times in the Quran. God created Adam with His hands and created his wife, Hawwa or Eve from Adam’s rib. -

Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: a Critical Evaluation of Two Translations

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.8, No.2, 2017 Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: A Critical Evaluation of Two Translations Izzeddin M. I. Issa Dept. of English & Translation, Jadara University, PO box 733, Irbid, Jordan Abstract This study is devoted to discuss the renditions of the prophets' names in the Holy Quran due to the authority of the religious text where they reappear, the significance of the figures who carry them, the fact that they exist in many languages, and the fact that the Holy Quran addresses all mankind. The data are drawn from two translations of the Holy Quran by Ali (1964), and Al-Hilali and Khan (1993). It examines the renditions of the twenty five prophets' names with reference to translation strategies in this respect, showing that Ali confused the conveyance of six names whereas Al-Hilali and Khan confused the conveyance of four names. Discussion has been raised thereupon to present the correct rendition according to English dictionaries and encyclopedias in addition to versions of the Bible which add a historical perspective to the study. Keywords: Mistranslation, Prophets, Religious, Al-Hilali, Khan. 1. Introduction In Prophets’ names comprise a significant part of people's names which in turn constitutes a main subdivision of proper nouns which include in addition to people's names the names of countries, places, months, days, holidays etc. In terms of translation, many translators opt for transliterating proper names thinking that transliteration is a straightforward process depending on an idea deeply rooted in many people's minds that proper nouns are never translated or that the translation of proper names is as Vermes (2003:17) states "a simple automatic process of transference from one language to another." However, in the real world the issue is different viz. -

The Wind-Catcher, a Traditional Solution for a Modern Problem Narguess

THE WIND-CATCHER, A TRADITIONAL SOLUTION FOR A MODERN PROBLEM NARGUESS KHATAMI A submission presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Glamorgan/ Prifysgol Morgannwg for the degree of Master of Philosophy August 2009 I R11 1 Certificate of Research This is to certify that, except where specific reference is made, the work described in this thesis is the result of the candidate’s research. Neither this thesis, nor any part of it, has been presented, or is currently submitted, in candidature for any degree at any other University. Signed ……………………………………… Candidate 11/10/2009 Date …………………………………....... Signed ……………………………………… Director of Studies 11/10/2009 Date ……………………………………… II Abstract This study investigated the ability of wind-catcher as an environmentally friendly component to provide natural ventilation for indoor environments and intended to improve the overall efficiency of the existing designs of modern wind-catchers. In fact this thesis attempts to answer this question as to if it is possible to apply traditional design of wind-catchers to enhance the design of modern wind-catchers. Wind-catchers are vertical towers which are installed above buildings to catch and introduce fresh and cool air into the indoor environment and exhaust inside polluted and hot air to the outside. In order to improve overall efficacy of contemporary wind-catchers the study focuses on the effects of applying vertical louvres, which have been used in traditional systems, and horizontal louvres, which are applied in contemporary wind-catchers. The aims are therefore to compare the performance of these two types of louvres in the system. For this reason, a Computational Fluid Dynamic (CFD) model was chosen to simulate and study the air movement in and around a wind-catcher when using vertical and horizontal louvres. -

Circular-40-Quran Memorization Competition

SHANTINIKETAN INDIAN SCHOOL, DOHA-QATAR Circular No. : 40/Circular/2019-20 Date : 04.11.2019 CIRCULAR FOR CLASSES KG-I to XII Dear Parents Asslamu Alaikum, Wahdathu Tahfeez-al-Qur’an under the Ministry of Awquaf and Islamic Affairs is conducting an Inter-school Quran Memorization competition in February-2020 as per the schedule below. The Students who are interested to participate should submit the Entry Form with a photograph to Mr. Fawzan / Mrs. Badrunnisa on or before 12th November, 2019. The following are the portions for memorization. Tick () the portion that you would like to participate: Level: 1 Level: 2 (From the first part of the Qur’an) (From the last part of the Qur’an) To No of Portions Class From Surah Beginning End Beginning End Surah (Ajza’) 7 Al-Baqara Al-An’am (verse-110) Az-Zumar (verse-32) An-Nas KG Al-Fajr An-Nas 8 Al-Baqara Al-A’raf (verse-87) Ya-Sin (verse-28) An-Nas I Al-Fajr An-Nas 9 Al-Baqara Al-Anfal (verse-40) Al-Ahzab (verse-31) An-Nas 10 Al-Baqara At-Tawbah (verse-92) Al-Ankaboot (verse-46) An-Nas II Abasa An-Nas 11 Al-Baqara Hud (verse-5) An-Naml (verse-56) An-Nas 12 Al-Baqara Yusuf (verse-52) Al-Furqan (verse-21) An-Nas III Al-Jinn An-Nas 13 Al-Baqara Ibrahim Al-Mu’minun An-Nas IV At-Talaq An-Nas 14 Al-Baqara An-Nahl Al-Anbya An-Nas 15 Al-Baqara Al-Kahf (verse-74) Al-Kahf (verse-75) An-Nas V Al-Hashr An-Nas 16 Al-Baqara Taha Al-Isra An-Nas 17 Al-Baqara Al-Hajj Al-Hijr An-Nas VI Ar-Rahman An-Nas 18 Al-Baqara Al-Furqan (verse-20) Yusuf (verse-53) An-Nas VII Adh-Dhariyat An-Nas 19 Al-Baqara An-Naml (verse-55) -

The Making of Prayer Circles (PC) and Prayer Direction Circles (PDC) Map

Ahmad S. Massasati, Ph.D. Department of Geography Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences United Arab Emirates University Email: [email protected] The Making of Prayer Circles (PC) and Prayer Direction Circles (PDC) Map Abstract Geographic Information Systems GIS has proven to be an essential tool of Automated Cartography. The problems of finding the direction to the City of Makkah is extremely important to Muslims around the globe to perform the five time daily prayer. The challenge to solve such a problem is a classical example of map projection on flat surface where distortion may give the wrong impression on directions. A prayer direction circles and a prayer circle system have been introduced using GIS to solve the problem. Using spherical triangulation solution with the city of Makkah at the center of the prayer circles, a prayer map was designed to solve the problem. Knowing that map making is an art as well as a science, Islamic calligraphy and designs were added for better enhancement of the map. Introduction Map making was always recognized as a science and an art. The science of map making deals with location and attributes, and is expected to provide accurate information. With Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technology, it is becoming 1 possible to make maps with a higher accuracy and speed. GIS also provides the mapmakers with a powerful tool to introduce maps to a wider range of audience in various scales and formats. The pictorial nature of cartographic language makes it the most understood form of communication for all of mankind. -

Tawaqquf and Acceptance of Human Evolution

2 | Theological Non-Commitment (Tawaqquf) in Sunni Islam and Its Implications for Muslim Acceptance of Human Evolution Author Biography Dr. David Solomon Jalajel is a consultant with the Prince Sultan Research Institute at King Saud University and holds a PhD in Arabic and Islamic Studies from the University of the Western Cape. Formerly, he was a lecturer in Islamic theology and legal theory at the Dar al-Uloom in Cape Town, South Africa. His research interests concern how traditional approaches to Islamic theology and law relate to contemporary Muslim society. He has published Women and Leadership in Islamic Law: A Critical Survey of Classical Legal Texts (Routledge), Islam and Biological Evolution: Exploring Classical Sources and Methodologies (UWC) and Expressing I`rāb: The Presentation of Arabic Grammatical Analysis (UWC). Disclaimer: The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in these papers and articles are strictly those of the authors. Furthermore, Yaqeen does not endorse any of the personal views of the authors on any platform. Our team is diverse on all fronts, allowing for constant, enriching dialogue that helps us produce high-quality research. Copyright © 2019, 2020. Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research 3 | Theological Non-Commitment (Tawaqquf) in Sunni Islam and Its Implications for Muslim Acceptance of Human Evolution Abstract Traditional Muslims have been resistant to the idea of human evolution, justifying their stance by the account of Adam and Eve being created without parents as traditionally understood from the apparent (ẓāhir ) meaning of the Qur’an and Sunnah. The account of the creation of these two specific individuals belongs to a category of questions that Sunni theologians refer to as the samʿiyyāt, “revealed knowledge.” These are matters for which all knowledge comes exclusively from Islam’s sacred texts. -

Ramiz Daniz the Scientist Passed Ahead of Centuries – Nasiraddin Tusi

Ramiz Daniz Ramiz Daniz The scientist passed ahead of centuries – Nasiraddin Tusi Baku -2013 Scientific editor – the Associate Member of ANAS, Professor 1 Ramiz Daniz Eybali Mehraliyev Preface – the Associate Member of ANAS, Professor Ramiz Mammadov Scientific editor – the Associate Member of ANAS, Doctor of physics and mathematics, Academician Eyyub Guliyev Reviewers – the Associate Member of ANAS, Professor Rehim Husseinov, Associate Member of ANAS, Professor Rafig Aliyev, Professor Ajdar Agayev, senior lecturer Vidadi Bashirov Literary editor – the philologist Ganira Amirjanova Computer design – Sevinj Computer operator – Sinay Translator - Hokume Hebibova Ramiz Daniz “The scientist passed ahead of centuries – Nasiraddin Tusi”. “MM-S”, 2013, 297 p İSBN 978-9952-8230-3-5 Writing about the remarkable Azerbaijani scientist Nasiraddin Tusi, who has a great scientific heritage, is very responsible and honorable. Nasiraddin Tusi, who has a very significant place in the world encyclopedia together with well-known phenomenal scientists, is one of the most honorary personalities of our nation. It may be named precious stone of the Academy of Sciences in the East. Nasiraddin Tusi has masterpieces about mathematics, geometry, astronomy, geography and ethics and he is an inventor of a lot of unique inventions and discoveries. According to the scientist, America had been discovered hundreds of years ago. Unfortunately, most peoples don’t know this fact. I want to inform readers about Tusi’s achievements by means of this work. D 4702060103 © R.Daniz 2013 M 087-2013 2 Ramiz Daniz I’m grateful to leaders of the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan Republic for their material and moral supports for publication of the work The book has been published in accordance with the order of the “Partner” Science Development Support Social Union with the grant of the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan Republic Courageous step towards the great purpose 3 Ramiz Daniz I’m editing new work of the young writer. -

00 Jenerik 39.Indd

SAYI 39 • 2012 OSMANLI ARAŞTIRMALARI THE JOURNAL OF OTTOMAN STUDIES Other Places: Ottomans traveling, seeing, writing, drawing the world A special double issue [39-40] of the Journal of Ottoman Studies / Osmanlı Araştırmaları Essays in honor of omas D. Goodrich Part I Misafir Editörler / Guest Editors Gottfried Hagen & Baki Tezcan Searchin’ his eyes, lookin’ for traces: Piri Reis’ World Map of & its Islamic Iconographic Connections (A Reading Through Bağdat and Proust)* Karen Pinto** Gözlerine Bakmak, İzler Aramak: Piri Reis’in 1513 Tarihli Dünya Haritası ve Onun İslâm İkonografisi ile İlişkileri (Bağdat 334 ve Proust Üzerinden Bir Okuma) Özet Osmanlı korsanı (sonradan amirali) Muhiddin Piri, yani Piri Reis’in 1513 tarihli dünya haritasından geriye kalan ve Atlantik Okyanusu ile Yeni Dünya’yı betimleyen kı- sım, haritacılık tarihinin en ünlü ve tartışmalı haritalarından biri sayılır. 1929’da Topka- pı Sarayı’nda bulunmasından beri, bu erken modern Osmanlı haritası, kaynak ve kökeni hakkında şaşırtıcı soruların ortaya atılmasına sebep olmuştur. Bazı araştırmacılar, kadim deniz kralları ya da uzaydan gelen yabancıların haritanın asli yaratıcıları olduğunu söylerken, diğerleri Kolomb’un kendi haritası ve erken Rönesans haritacılarına bağladılar boşa çıkan ümitlerini. Cevap verilmeden kalan bir soru da, İslâm haritacılığının Piri Reis’in çalışma- larını nasıl etkilediği. Bu makale, klasik İslâm haritacılık geleneği ile Piri Reis’in haritası arasındaki bugüne kadar fark edilmemiş ikonografik ilişkileri gözler önüne seriyor. Anahtar kelimeler: Piri Reis, Piri Reis’in 1513 tarihli dünya haritası, Osmanlı hari- tacılığı, İslâm dünyasında haritacılık, ‘Acâ’ibü’l-mahlukat geleneği, İslâm dünyasında elyazması süslemeciliği. When a man is asleep, he has in a circle round him the chain of the hours, the sequence of the years, the order of the heavenly host. -

Maps As the Heritage of Mankind 575

The Keynote Address Maps as the Heritage of A1ankind* REVEREND FRANCIS J. HEYDEN, s.J. Astronomer, Georgetown Univ., Washington, D. C. T IS unusual for an astronomer to give a an old envelope. As long as he indicates the I keynote address to people who are earth right number of turns in the road and shows bound in their avocation of mapping the you the number of stt'eams you are to cross, earth. Of course, you could not have done you can probably find the place I\'ithout too very much without stars, without the rota much difficulty. tion of the earth or without the timekeepers In the same way, some of the most primi who give us the longitudes we need for any tive maps have shown the the right number of distance to be measured on the surface of the turns in a river; they have shown the por earth. tages at waterfalls and even have used camp Having been in charge of a time service sites bet\\'een one day's travel, \I'hich was the similar to that at the Naval Observatory in custom among the Indians of this country, the Philippines for three years, I presume I rather than longitudes. Each campsite, am qualified for at least one dimension, and whether you were climbing a mountain for a that is longitude. day or walking rapidly across a plain, would I am going to talk to you, however, about be spaced equidistant apart. something entirely different from the meas Thus, the sources of scale in many very old urement of longitude. -

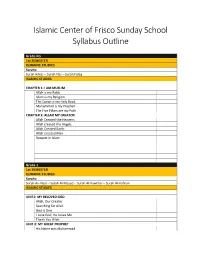

Islamic Center of Frisco Sunday School Syllabus Outline

Islamic Center of Frisco Sunday School Syllabus Outline Grade KG 1st SEMESTER QURANIC STUDIES Surahs: Surah Ikhlas – Surah Nas – Surah Falaq ISLAMIC STUDIES CHAPTER 1: I AM MUSLIM Allah is my Rabb Islam is my Religion The Quran is my Holy Book Muhammad is my Prophet The Five Pillars are my Path CHAPTER 2: ALLAH MY CREATOR Allah Created the Heavens Allah created the Angels Allah Created Earth Allah Created Man Respect in Islam Grade 1 1st SEMESTER QURANIC STUDIES Surahs: Surah An-Nasr – Surah Al-Masad - Surah Al-Kawthar – Surah Al-Kafirun ISLAMIC STUDIES UNIT1: MY BELOVED GOD Allah, Our Creator Searching for Allah God is One I Love God, He Loves Me Thank You Allah UNIT 2: MY GREAT PROPHET His Name was Muhammad Muhammad as a Child Muhammad Worked Hard The Prophet’s Family Muhammad Becomes a Prophet Sahaba: Friends of the Prophet UNIT 3: WORSHIPPING ALLAH Arkan-ul-Islam: The Five Pillars of Islam I Love Salah Wud’oo Makes me Clean Zaid Learns How to Pray UNIT 4: MY MUSLIM WORLD My Muslim Brothers and Sisters Assalam o Alaikum Eid Mubarak UNIT 5: MY MUSLIM MANNERS Allah Loves Kindness Ithaar and Caring I Obey my Parents I am a Muslim, I must be Clean A Dinner in our Neighbor’s Home Leena and Zaid Sleep Over at their Grandparents’ Home Grade 2 1st SEMESTER QURANIC STUDIES Surahs: Surah Al-Quraish – Surah Al-Maun - Surah Al-Humaza – Surah Al-Feel ISLAMIC STUDIES UNIT1: IMAN IN MY LIFE I Think of Allah First I Obey Allah: The Story of Prophet Adam (A.S) The Sons of Adam I Trust Allah: The Story of Prophet Nuh (A.S) My God is My Creator Taqwa: -

M a Late-11Th-Century Copy of Ibn Comes to Us from the Middle East and Central and Inner Asia

ARAMCOWORLD.COMARAMC O W O RLD.C O M MAPS 2020 1441–1442 GREGORIAN HIJRI shows how the Nile emerges from the mythical Mountains of the Moon (now Ethiopia), flows through multiple cataracts and heads north, crosses the equator to pass through the lands of Nubia, Aswan and Beja toward Fustat (medieval Cairo) and finishes in the Nile Delta near Dumyat (Damietta), where it empties into the Mediterranean Sea. Cartographers replicated this depiction of the Nile in various ways in every cartographic manuscript thereafter for centuries. As copies proliferated throughout the medieval Islamic Middle East, this helped establish what became, in effect, the world’s first geographical atlas series. Introduction and calendar captions by KAREN C. PINTO The maps pictured for the months of May and August are by different authors from that “Islamic atlas series” spawned by al-Khwarizmi. May shows the exceptional, three-folio map The richest–surviving heritage of premodern maps of the world of the Mediterranean Sea from a late-11th-century copy of Ibn comes to us from the Middle East and Central and Inner Asia. Hawqal’s Kitab surat al-‘ard. It is the earliest-known copy of the most-mimetic map of the Mediterranean. On it one can see the outlines of the Iberian Peninsula, the Calabrian Peninsula, the Al-Khwarizmi’s rom the Babylonian clay tablet of 600 bce to Katip as the Bahr al-Muhit (Encircling Ocean), which was the most Peloponnese, Constantinople, the map of the Nile Çelebi’s map of Japan drawn in 1732, geographers and basic marker of world maps up through medieval periods.