America's Rental Housing 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Affordable Housing Lease Addendum HOME And/Or NHTF Assisted

Affordable Housing Lease Addendum HOME and/or NHTF Assisted It is possible that the unit for which you are applying has been assisted with federal funds and is governed by the HOME Investment Partnerships Program 24 CFR Part 92 or the National Housing Trust Fund Program (NHTF) 24 CFR Part 93, as amended. The HOME program requires that in order to be eligible for admittance into this unit, your total household annual income must be at or below 50% of median income (very low- income as defined under 24 CFR Part 92). The National Housing Trust Fund program requires that in order to be eligible for admittance into this unit, your total household annual income must be at or below 30% of median income (extremely low-income as defined under 24 CFR Part 93). If your unit is initially designated as a HOME unit and after initial occupancy and income determination, your total household annual income increases above 80% of median income (low-income as defined under 24 CFR Part 92), you will be required to pay 30% of your adjusted gross monthly income for rent and utilities, except that tenants of HOME-assisted units that have been allocated low-income housing tax credits by a housing credit agency pursuant to section 42 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 (26 U.S.C.42) must pay rent governed by section 42. If your unit is initially designated as a NHTF unit and after initial occupancy and income determination, your total household annual income increases above 30% of median income (household is no longer extremely low income), you may stay in your NHTF assisted unit. -

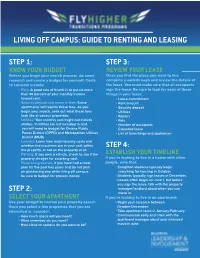

Guide to Renting and Leasing Digital

LIVING OFF CAMPUS: GUIDE TO RENTING AND LEASING STEP 1: STEP 3: KNOW YOUR BUDGET REVIEW YOUR LEASE Before you begin your search process, do some Once you find the place you want to live, research and create a budget for yourself. Costs complete a walkthrough and review the details of to consider include: the lease. You must make sure that all occupants Rent: A good rule of thumb is to put no more sign the lease. Be sure to look for each of these than 30 percent of your monthly income things in your lease: toward rent. Lease commitment Security deposit and move-in fees: Some Rent amount apartments will require these fees. As you Security deposit begin your search, seek out what these fees Utilities look like at various properties. Repairs Utilities: Your monthly rent might not include Pets utilities. If utilities are not included in rent, Number of occupants you will need to budget for Omaha Public Extended leave Power District (OPPD) and Metropolitan Utilities List of furnishings and appliances District (MUD). Laundry: Learn how much laundry costs and whether the machines are in your unit, within STEP 4: the property, or not on the property at all. Parking: If you own a vehicle, check to see if the ESTABLISH YOUR TIMELINE property chrages for a parking spot. If you’re looking to live in a house with other Food and groceries: If you have had a meal people, note that: plan for the past two years and do not plan Creighton students typically begin on purchasing one while living o campus, searching for housing in October. -

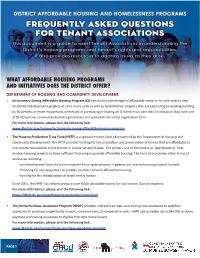

What Affordable Housing Programs and Initiatives

WHAT AFFORDABLE HOUSING PROGRAMS AND INITIATIVES DOES THE DISTRICT OFFER? DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT: • Inclusionary Zoning Affordable Housing Program (IZ) sets aside a percentage of affordable rental or for-sale units in new residential development projects of 10 or more units as well as rehabilitation projects that are expanding an existing building by 50 percent or more. Households interested in purchasing or leasing an IZ home must take the IZ orientation class with one of DHCD partner community-based organizations and complete the online registration form. For more information, please visit the following link: www.dhcd.dc.gov/service/inclusionary-zoning-affordable-housing-program • The Housing Production Trust Fund (HPTF) is a special revenue fund administered by the Department of Housing and Community Development. The HPTF provides funding for the production and preservation of homes that are affordable to low-income households in the District in a wide variety of ways. The primary use of the fund is as “gap financing” that enables housing projects to have sufficient financing to provide affordable housing. The fund also provides other forms of assistance including: - pre-development loans to assist nonprofit housing developers in getting low income housing projects funded; - financing for site acquisition to provide locations to build affordable housing; - funding for the rehabilitation of single family homes. Since 2001, the HPTF has helped produce over 9,000 affordable homes for low income District residents. For more information, please visit the following link: https://dhcd.dc.gov/page/housing-production-trust-fund • The Home Purchase Assistance Program (HPAP) provides interest-free loans and closing cost assistance to qualified applicants to purchase single-family houses, condominiums, or cooperative units. -

So… You Wanna Be a Landlord? Income Tax Considerations for Rental Properties

So… you wanna be a landlord? Income tax considerations for rental properties November 2020 Jamie Golombek & Debbie Pearl-Weinberg Tax and Estate Planning, CIBC Private Wealth Management Considering becoming a landlord? You’re not alone. According to recent a CIBC poll, more than one in four Canadian homeowners are either already landlords (15%) or plan to earn rental income (11%) by renting out space in their primary residence or from a separate rental property. And, nearly two in five (37%) homeowners say they’d opt for a home with a source of rental income if buying a home today. While there are many financial and legal issues to consider as a landlord, make sure that you don’t overlook tax considerations of earning rental income. Whether you’re purchasing a residential or commercial property for the purpose of leasing it out, or you are considering renting your home or part of your home, this report highlights some of the more common tax issues you should consider before taking the plunge! Rental property or business? The first question you need to consider is whether the rental income you earn will be treated as income from property (i.e. investment income) or as income from a business, since each has different tax implications. When you rent out real estate, your income is treated as property income if you provide only basic services, such as utilities (e.g. light and heating), parking and laundry facilities. If you provide additional services, such as cleaning, security and / or meals, then it may be considered a business. -

Single-Room Occupancy Uses

City Council Report City Council Meeting: March 26, 2019 Agenda Item: 7.A To: Mayor and City Council From: David Martin, Director, City Planning Subject: Introduction and Adoption of an Urgency Interim Zoning Ordinance Regarding Single-Room Occupancy Uses Recommended Action Staff recommends Council introduce and adopt an urgency interim zoning ordinance to prohibit Single-Room Occupancy (SRO) uses citywide on an interim basis in order to prevent the proliferation and over-concentration of SRO uses that are not 100% Affordable Housing Projects or certain specialized housing uses such as emergency shelters, transitional housing, and supportive housing. This urgency interim zoning ordinance would allow for study of revised development standards, land use regulations, use classifications, and additional requirements related to physical design or amenity plans, for SRO uses in order to protect the public health, safety and welfare. Executive Summary Over the years, City staff, decisionmakers, and community members have had numerous discussions regarding housing development in the City and how to create effective housing policies, programs, and regulatory tools to address the need for more development of a variety of types and sizes of housing options. In particular, a need has been identified for development of new affordable housing and supportive housing, and market-rate multi-family projects near transit, in order to offer attractive and feasible opportunities for a range of individuals and families to live in Santa Monica. The Downtown Community Plan was adopted by Council on July 25, 2017. Framed as a “housing first” approach, it envisioned a robust mix of housing types serving a wide range of household sizes and income levels. -

Frequencies Between Serial Killer Typology And

FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS A dissertation presented to the faculty of ANTIOCH UNIVERSITY SANTA BARBARA in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY in CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY By Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori March 2016 FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS This dissertation, by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, has been approved by the committee members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: _______________________________ Ron Pilato, Psy.D. Chairperson _______________________________ Brett Kia-Keating, Ed.D. Second Faculty _______________________________ Maxann Shwartz, Ph.D. External Expert ii © Copyright by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, 2016 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS LERYN ROSE-DOGGETT MESSORI Antioch University Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA This study examined the association between serial killer typologies and previously proposed etiological factors within serial killer case histories. Stratified sampling based on race and gender was used to identify thirty-six serial killers for this study. The percentage of serial killers within each race and gender category included in the study was taken from current serial killer demographic statistics between 1950 and 2010. Detailed data -

Understanding Youth Gangs in Yakima County

Is My Child At Risk For Gang Involvement? Parents play a crucial role in keeping their children out of gangs. Unfortunately many parents lack important information Understanding about what to look for. Youth between 12-14 years of age are most likely to consider joining a gang; however children as young as first grade can be recruited. You should know that kids who have school difficulties, a lack of parental supervision, use alcohol or other drugs, are often Youth Gangs truant from school or very prone to “following the pack” are most at risk of gang involvement. in Yakima County Why Do Kids Join Gangs? Adolescence is a time in life when children begin to define their own identity. Many seek out new peer groups as a means Yakima County Resources of gaining acceptance. Gangs can meet this need. Gangs can provide things children may not get at home or elsewhere — not just acceptance, but structure, money, food, activities, companionship, and even love. Kids don’t run toward gangs, they are running away from something else and find gangs. You can help prevent gang involvement by ensuring all your 211 is a local resource help line that can refer you children’s needs are met in some other way. to parenting programs, counselors, mental health therapists, and substance abuse providers. Southeast Community Center/OIC/Building the Bridges gang outreach workers can be reached at 509-575-6114 Behaviors Associated With Gang Involvement Randy Town, ESD 105 Yakima County Gang Youth who are involved in gangs may exhibit changes in behavior. -

DC's Vanishing Affordable Housing

An Affiliate of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities 820 First Street NE, Suite 460 Washington, DC 20002 (202) 408-1080 Fax (202) 408-8173 www.dcfpi.org March 12, 2015 Going, Going, Gone: DC’s Vanishing Affordable Housing By Wes Rivers Introduction Rapidly rising housing costs led to a substantial loss of low-cost rental housing in the District over the last decade, yet there was little growth in wages for many residents, which means that rent is increasingly eating away at household budgets. As the District’s high cost of living continues to outpace incomes, more and more residents struggle to pay for housing while also meeting other necessities like food, clothing, health care, and transportation. The loss of affordable housing threatens the physical and mental health of families, makes it harder for adults to find and keep a job, creates instability for children that makes it hard to focus at school, and leaves thousands at risk of homelessness at any given moment. This analysis looks at the costs of rent and utilities paid by District residents over the last decade, and how these trends have affected residents’ ability to afford and live in DC, using data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. The findings suggest that policymakers need a comprehensive strategy to preserve the low-cost housing that now exists and to create more affordable housing options in the city. Rents have grown sharply but incomes have not for many DC households. For example, rents for residents with incomes of about $22,000 a year increased $250 a month over the past decade, adjusting for inflation, while incomes remained flat. -

Ph6.1 Rental Regulation

OECD Affordable Housing Database – http://oe.cd/ahd OECD Directorate of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs - Social Policy Division PH6.1 RENTAL REGULATION Definitions and methodology This indicator presents information on key aspects of regulation in the private rental sector, mainly collected through the OECD Questionnaire on Affordable and Social Housing (QuASH). It presents information on rent control, tenant-landlord relations, lease type and duration, regulations regarding the quality of rental dwellings, and measures regulating short-term holiday rentals. It also presents public supports in the private rental market that were introduced in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Information on rent control considers the following dimensions: the control of initial rent levels, whether the initial rents are freely negotiated between the landlord and tenants or there are specific rules determining the amount of rent landlords are allowed to ask; and regular rent increases – that is, whether rent levels regularly increase through some mechanism established by law, e.g. adjustments in line with the consumer price index (CPI). Lease features concerns information on whether the duration of rental contracts can be freely negotiated, as well as their typical minimum duration and the deposit to be paid by the tenant. Information on tenant-landlord relations concerns information on what constitute a legitimate reason for the landlord to terminate the lease contract, the necessary notice period, and whether there are cases when eviction is not permitted. Information on the quality of rental housing refers to the presence of regulations to ensure a minimum level of quality, the administrative level responsible for regulating dwelling quality, as well as the characteristics of “decent” rental dwellings. -

The Impact of Affordable Housing on Communities and Households

Discussion Paper The Impact of Affordable Housing on Communities and Households Spencer Agnew Graduate Student University of Minnesota, Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs Research and Evaluation Unit Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Does Affordable Housing Impact Surrounding Property Values? .................... 5 Chapter 2: Does Affordable Housing Impact Neighborhood Crime? .............................. 10 Chapter 3: Does Affordable Housing Impact Health Outcomes? ..................................... 14 Chapter 4: Does Affordable Housing Impact Education Outcomes? ............................... 19 Chapter 5: Does Affordable Housing Impact Wealth Accumulation, Work, and Public Service Dependence? ........................................................................................................ 24 2 Executive Summary Minnesota Housing finances and advances affordable housing opportunities for low and moderate income Minnesotans to enhance quality of life and foster strong communities. Overview Affordable housing organizations are concerned primarily with helping as many low and moderate income households as possible achieve decent, affordable housing. But housing units do not exist in a vacuum; they affect the neighborhoods they are located in, as well as the lives of their residents. The mission statement of Minnesota Housing (stated above) reiterates the connections between housing, community, and quality -

Religious-Verses-And-Poems

A CLUSTER OF PRECIOUS MEMORIES A bud the Gardener gave us, A cluster of precious memories A pure and lovely child. Sprayed with a million tears He gave it to our keeping Wishing God had spared you If only for a few more years. To cherish undefiled; You left a special memory And just as it was opening And a sorrow too great to hold, To the glory of the day, To us who loved and lost you Down came the Heavenly Father Your memory will never grow old. Thanks for the years we had, And took our bud away. Thanks for the memories we shared. We only prayed that when you left us That you knew how much we cared. 1 2 AFTERGLOW A Heart of Gold I’d like the memory of me A heart of gold stopped beating to be a happy one. I’d like to leave an afterglow Working hands at rest of smiles when life is done. God broke our hearts to prove to us I’d like to leave an echo He only takes the best whispering softly down the ways, Leaves and flowers may wither Of happy times and laughing times The golden sun may set and bright and sunny days. I’d like the tears of those who grieve But the hearts that loved you dearly to dry before too long, Are the ones that won’t forget. And cherish those very special memories to which I belong. 4 3 ALL IS WELL A LIFE – WELL LIVED Death is nothing at all, I have only slipped away into the next room. -

Renting Vs. Buying

renting vs. buying: 6 things to consider After years of renting and frequent moving, you may start to ask yourself: Should I buy a house? While many experts have weighed in on the pros and cons of renting vs. buying, the truth is-it depends on your individual situation. So, if you're not sure if renting or owning is right for you, here are a few things to consider. 1. Where do you want to live? If you're looking to live in a big city, you may have more options in the rental market. But if you prefer the suburbs, buying may be a better option since single family home rentals can be few and far between. 2. How long do you plan to stay? Consider your "five-year plan." If your job situation is in flux or you plan to move again in a few years, renting may make more sense. On the other hand, if you're ready to settle down in a certain area, making the investment to buy could pay off long-term. 3. Are you ready to be your own landlord? When you're renting and your sink springs a leak, your landlord will handle the maintenance and cost of any repairs. But if you're the homeowner, that responsibility falls on you. On the upside, owning your own home also gives you the freedom to do your own remodeling or repairs and to hire the contractor of your choice. 4. How important is long-term payoff? Buying a house is an investment in your future.