Abney Korn Final Format Approved LW 11-29-12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morning Phase", Il Nuovo Album Di BECK

MARTEDì 25 FEBBRAIO 2014 È disponibile da oggi nei negozi tradizionali e negli store digitali "Morning phase", il nuovo album di BECK. L'album, a poche ore dalla pubblicazione, è già presente nella TopTen di iTunes dei principali paesi Beck, è uscito oggi il nuovo album del mondo a cominciare dagli Stati Uniti e il Canada, passando per la "Morning phase" Gran Bretagna e i paesi del nord Europa fino ad arrivare all'Italia. Il disco già in TopTen su iTunes "Morning phase" è il dodicesimo lavoro di studio del cantautore americano ed è il primo disco contenente materiale inedito dall'uscita di "Modern Guilt" del 2008. ANDREA LECCARDI In scaletta 12 brani inediti: "Morning", "Heart Is A Drum", "Say Goodbye", "Waking Light", "Unforgiven", "Wave", "Don't Let It Go", "Blackbird Chain", "Evil Things", "Blue Moon", "Turn Away", "Country Down". Intervistato a proposito del nuovo album dal magazine inglese Q, Beck ha chiarito nel dettaglio quali sono state le ispirazioni e le fonti che hanno dato vita ai brani del nuovo album: "Sono tornato alla musica della [email protected] mia giovinezza e delle mie radici: parlo di Neil Young, Gram Parsons e SPETTACOLINEWS.IT Crosby, Stills, & Nash. Ricordo sempre il suono di quei dischi e di quelle registrazioni, erano parte di una cultura mentre crescevo. Fanno parte del mio imprinting di crescita, che mi piaccia o meno. Forse rifiutavo questa musica quando ho cominciato a suonare, perché cercavo di trovare la mia identità. Ma sia io sia tutti quelli che hanno suonato su questo disco, siamo cresciuti tutti in California e quindi questo tipo di musica è inevitabilmente parte del nostro DNA". -

ACRONYMX-Round2 HSNCT.Pdf

ACRONYM X - Round 2 1. In a 1978 comic book, this athlete fights against and later joins forces with Superman to defeat an alien invasion. Trevor Berbick was the last man to compete against this athlete, who won a Supreme Court case in 1971 concerning his refusal to be drafted. This man, who lit the (*) cauldron at the 1996 Summer Olympics, rejected what he called his "slave name" after converting to Islam. George Foreman was defeated at the "Rumble in the Jungle" by, for 10 points, what heavyweight boxer formerly known as Cassius Clay? ANSWER: Muhammad Ali [accept Cassius Clay before the end] <Nelson> 2. In this series, Scott Clarke attempts to demonstrate an implausible theory by stabbing a paper plate. The band Survive produced music for this series, which also repeatedly makes use of The Clash's song "Should I (*) Stay Or Should I Go." A character on this series, whose real name, may be Jane Ives, is played by Millie Bobbie Brown and steals Eggos from a supermarket some time before following a monster into the Upside Down. Will Byers disappears at the beginning of, for 10 points, what supernatural-oriented Netflix series? ANSWER: Stranger Things <Nelson> 3. This man's directing credits include a 2007 film about a historically black college's debate team titled The Great Debaters. In a 2014 film, this actor portrayed a low-lying hardware store employee who is forced to use his experience as a former black ops killing machine. This star of the Antoine Fuqua [FOO-kwuh] film (*) The Equalizer won an Oscar for another of Fuqua's films, in which he plays Alonzo Harris, a man initiating a fellow police officer. -

UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA Fundada En 1867

UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA Fundada en 1867 Abstract The topic of this research is “Improving English Pronunciation and Listening Skills through Music.”This work was designed in order to create a booklet based on the use of songs to help university students improve their English. Therefore, three methods are considered to develop this process. The first one is the Bibliographic method in order to develop the Theoretical Framework, which contains information about this research work from books, articles, and websites. The second and third ones are the qualitative and quantitative methods, which are useful to describe and analyze information from interviews applied to an expert, and a survey to university students used at the beginning and at the end of the application of our project. Finally, to complement our research, we created a booklet that includessix nursery rhymes and six songs along with their lyrics, some activities, and the steps to follow in order to use this booklet accurately. Key words: songs, listening skills, pronunciation, music, motivation. Verónica Alvarado & David Matailo 1 UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA Fundada en 1867 Table of contents ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................... 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................... 2 AUTHORSHIP ..................................................................................................................... 9 DEDICATION .................................................................................................................. -

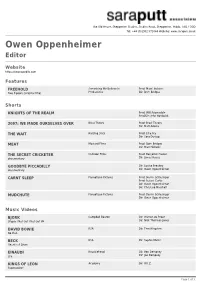

Owen Oppenheimer Editor

The Old House, Shepperton Studios, Studios Road, Shepperton, Middx, TW17 OQD Tel: +44 (0)1932 571044 Website: www.saraputt.co.uk Owen Oppenheimer Editor Website https://owenopedits.com Features FREEHOLD Something We Believe In Prod: Matt Hitchens Two Pigeons (original title) Productions Dir: Dom Bridges Shorts KNIGHTS OF THE REALM Prod: Will Adamsdale Prod/Dir: John Hardwick 2097: WE MADE OURSELVES OVER Blast Theory Prod: Blast Theory Dir: Matt Adams THE WAIT Rattling Stick Prod: Ellie Fry Dir: Sara Dunlop MEAT Mustard Films Prod: Dom Bridges Dir: Matt Hichens THE SECRET CRICKETER Outsider Films Prod: Benjamin Howell documentary Dir: James Rouse GOODBYE PICCADILLY Dir: Louise Breakey documentary Dir: Owen Oppenheimer CARNT SLEEP Panopticon Pictures Prod: Derrin Schlesinger Prod: Russel Curtis Dir: Owen Oppenheimer Dir: Christine Marshall MUDCHUTE Panopticon Pictures Prod: Derrin Schlesinger Dir: Owen Oppenheimer Music Videos BJORK Campbell Beaton Dir: Warren du Preez Utopia / Not Get / Not Get VR Dir: Nick Thornton Jones DAVID BOWIE RSA Dir: Tom Hingston No Plan BECK RSA Dir: Sophie Muller Heart is A Drum EINAUDI Knucklehead Dir: Ben Dempsey Life Dir: Joe Dempsey KINGS OF LEON Academy Dir: W.I.Z. Supersoaker Page 1 of 3 JAKE BUGG HLA Dir: John Hardwick Seen It All EMILI SAND? Academy Dir: W.I.Z. Clown KYLIE MINOGUE Parlophone Dir: Kylie Minogue Flower THE KILLS Academy Dir: Sophie Muller Satellite / Tape Song / Last Days of Magic THE RACONTEURS Factory Dir: Sophie Muller Levels (live) MARINA & THE DIMONDS Academy Dir: Kim Gehrig Shampain -

Museum Discovers Unmarked Grave

NONPROFIT ORGANIZATION VOTE IN OUR ONLINE POLL WWW.BAYLOR.EDU/LARIAT U.S. POSTAGE HEALTH CARE CRISIS A CONCERN FOR YOU?: PAID BAYLOR UNIVERSITY ROUNDING UP CAMPUS NEWS SINCE 1900 THE BAYLOR LARIAT WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 2008 Museum discovers unmarked grave Ranger Company F, a Public Safety site was used over a century ago as a remains undisturbed by outsiders,” By Victoria Mgbemena Education Center and the expansion pauper cemetery for people who could Johnson said. “The open field behind Staff writer of a banquet hall. A final report for the not afford burial arrangements. The the museum has fencing around it and excavation is set for later this year. land on the gravesite has been used is monitored by security personnel so Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and “It almost seemed as if the inter- as a dumping ground for debris from we don’t have people going down in Museum officials did not intend to ments occurred over night,” said Byron the tornado that hit Waco in 1953. the excavation trenches or wandering uncover the past as they were making Johnson, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame In more recent times, waste materials around.” plans for the future two summers ago. and Museum Director. “We found a from incinerators have been dumped According to Christina Stopka, A collection of unmarked graves was high density of graves that could not on the site. Johnson said that specific Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Muse- unearthed as officials completed plans be removed without careful evalua- regulations from the Texas Historical um deputy director, an independent Jeff Leslie/Lariat staff to lay utility lines and begin work on tion and filed for a permit to excavate Commission were required to carry archaeology contractor based out of building additions to the museum and move the remains to another loca- out the excavations. -

Ginosko Literary Journal #17 Winter 2015�16 73 Sais Ave San Anselmo CA 94960

1 Ginosko Literary Journal #17 Winter 2015-16 www.GinoskoLiteraryJournal.com 73 Sais Ave San Anselmo CA 94960 Robert Paul Cesaretti, Editor Member CLMP Est. 2002 Writers retain all copyrights Cover Art “Beach” by Sarah Angst www.SarahAngst.com 2 Ginosko (ghin-océ-koe) A Greek word meaning to perceive, understand, realize, come to know; knowledge that has an inception, a progress, an attainment. The recognition of truth from experience. γινώσκω 3 To write the red of a tomato before it is mixed into beans for chili is a form of praise. To write an image of a child caught in war is confession or petition or requiem. To write grief onto a page of lined paper until tears blur the ink is often the surest access to giving or receiving forgiveness. To write a comic scene is grace and beatitude. To write irony is to seek justice. To write admission of failure is humility. To be in an attitude of praise or thanksgiving, to rage against God, or to open one's inner self and listen, is prayer. To write tragedy and allow comedy to arise between the lines is miracle and revelation. Pat Schneider 4 C O N T E N T S Say it with Feathers Jay Merill Sainthood Old Woman Hanging Out Wash High Contrast Mitchell Krockmalnik Grabois HE DIDN’T REFUSE Sreedhevi Iyer The Waters of Babylon Andrew Lee-Hart Breast Fragments When the World Was Tender The Wolves Have Sheared the Sun The Prophet of Horus Grant Tabard Conversations in an Idle Car Filling in Jack C Buck The Man Who Lost Everything Erica Verrillo Doused Your Summer Dress Magenta Stockings Promenade John Greiner Dead Fish Jono Naito Misnamed Ghetto Melissa Brooks A Country Girl Rudy Ravindra 5 Heavy Compulsion Samuel Vargo The Company of Strangers Michael Campagnoli Lions Venetian Balloons C. -

Opening Game Against the San Francisco Bracelets Made Possible by the Paramedics in Giants When Sucker-Punched to the Ground Santa Clara County

Where’s Waldo? No Place Like Work Space Helmet & Bicycle S. Australia addresses A great center takes The two go together like rural routes listening to the floor fun and safety The National Academies of Emergency Dispatch September/October 2012 THEJOURNAL JOURNALOF EMERGENCY DISPATCH Get Your Motor Runnin’ Motorcycle rescue units arrive on the scene emergencydispatch.org PROTECT THEM SEND THE RIGHT INFORMATION Quickly sending the RIGHT on-scene information to responding officers and updating it in real-time can help save lives. That’s what the Police Priority Dispatch System™ does better than any other. When your team takes a 9-1-1 call using ProQA® dispatch software, you can be confident that both your new and veteran dispatchers are doing it RIGHT and that responding officers are receiving the information they need to protect themselves and the citizens around them. “Information is the reduction of uncertainty” ProQA Dispatch Software— reducing uncertainty for over 30 years 800.363.9127 www.prioritydispatch.net 2 THE JOURNALsend | emergencydispatch.org the right information. at the right time. to the right people—every call. 8.25x10.875 ProtectThemAd.indd 1 11/4/11 11:48 AM INSIDE the g columns PROTECT THEM 4 | Contributors JOURNAL 5 | Dear Reader SEND THE RIGHT INFORMATION SEPTEMBER·OCTOBER 2012 | vOL. 14 NO. 5 6 | President’s Message 7 | Ask Doc 8 | Police Beat 9 | Standards of Quality 42 | Retro Space g industry insider 11 | Latest news updates g departments BestPractices 18 | FAQ The difference between trauma versus medical is not always clear-cut 19 | ACE Achievers Central Lane County, Ore., is model for how dispatching is done 21 | Navigator Rewind Mob mentality puts responders features at risk. -

Follow Chelsea Toves @Awchels

THEPHOTO BY ISAAC PIERCE VALHALLA MARCH 25, 2015 LAKE STEVENS HIGH SCHOOL [email protected] VOLUME 87 ISSUE 6 News 2 March Madness: club fair in full swing by Abby Iblings This semester, LSHS decided to go about club fair in a whole new Photographer way. All of the different clubs recieved one day during the entire month of March to get students interested in joining their club. They held doors, handed out candy, held events at lunch, played music during passing periods and waved goodbye as buses left campus. There is a total of 23 clubs participating in the March Madness Month. This way, every club that wanted to be featured, could be and have more time to show the student body what they are all about. The new idea was thought up for the individual- ity for the clubs themselves instead of a one day competition at lunches where each club receives an area to hold an event and information table. Each club had to sign up for a day to host their activities. They also shared information about their clubs over morning an- nouncements. Some clubs, like FCCLA provided information, games and cookies or can- dy. GSA held doors and played music in the hallways. On their day, Dead Poets’ Society PHOTO BY ABBY IBLINGS showed the “Dead Poets’ Society” movie after school and provided trivia during lunch. Courtney Klein, Sierra Holden, Shaelyn Huot, and Heather Smith man the National Honor Society Magic the Gathering handed out Magic cards to students in the morning and on their table during lunch. -

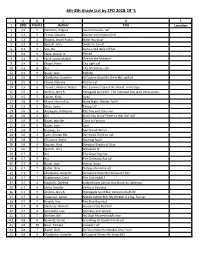

6Th-8Th Grade List by ZPD 2018-19~S

6th-8th Grade List by ZPD 2018-19~S A B C D E 1 ZPD Points Author Title Location 2 3.2 5 Hamilton, Virginia Second Cousins aef 3 3.3 5 Friend, Natasha Bounce caf [stepfamilies] 4 3.3 4 Rhodes, Jewell Parker Ninth Ward caf 5 3.3 5 Spinelli, Jerry Smiles to Go caf 6 3.3 4 Vos, Ida Anna is Still Here hff/fwf 7 3.4 5 Flake, Sharon G. Pinned 8 3.4 6 Hunt, Lynda Mullaly One for the Murphys 9 3.4 6 Mazer, Harry City Light caf 10 3.5 8 Avi City of Orphans ahf 11 3.5 5 Bauer, Joan Tell Me 12 3.5 7 Choldenko, Gennifer Al Capone Does My Shirts Bk1 caf/huf 13 3.5 5 Friend, Natasha Perfect caf 14 3.5 6 Hurwitz, Michele Weber The Summer I Saved the World…in 65 Days 15 3.5 6 Jenkins, Jerry B. Renegade Spirit Bk1: The Tattooed Rats [end times series] 16 3.5 5 Larson, Kirby Duke 17 3.5 4 Mazer, Norma Fox Good Night, Maman fw/hf 18 3.5 9 Moss, Jenny Taking Off 19 3.6 4 Applegate, Katherine The One and Only Ivan 20 3.6 4 Avi Don’t You Know There’s a War On? awf 21 3.6 6 Bauer, Jennifer Close to Famous 22 3.6 6 Bauer, Joan Soar 23 3.6 7 Knowles, Jo See You at Harry's 24 3.6 4 Lyon, George Ella Borrowed Children caf 25 3.6 7 O'Conner, Sheila Sparrow Road 26 3.6 9 Sepetys, Ruta Between Shades of Gray 27 3.6 7 Spinelli, Jerry Milkweed hf 28 3.7 5 Avi The Good Dog fwa 29 3.7 3 Avi The Christmas Rat caf 30 3.7 6 Bauer, Joan Almost Home 31 3.7 7 Butler, Dori Sliding into Home spf 32 3.7 7 Choldenko, Gennifer Al Capone Does My Homework Bk3 33 3.7 7 Grabenstein, Chris The Crossroads f 34 3.7 4 Haworth, Danette Violet Raines Almost Got Struck by Lightning 35 3.7 4 Holm, Jennifer Turtle in Paradise 36 3.7 5 Jenkins, Jerry B. -

Road1312 Sept6,15 Playlist

Play List for ROAD HOME Road #1312 Date: Sept 6.15 RH.FM launch of roadhome.fm KIND SELECTION ARTIST SOURCE TIME talk bob on new poetry, music, bob 4:04 roadhome.fm OPENING theme Road Home theme The McDades http://www.themcdades.com 1:02 poem The Muse of Universes Alice Major (Standard Candles) 1:23 The Universe Gregory Alan Isakov The Weatherman 3:44 poem The Music of the Spheres Ernesto Cardinal (katabasis.co.uk) 1:33 Beautiful World Eliza Gilkyson Beautiful World 5:14 poet Inventing the Hawk Lorna Crozier (The Blue Hour of the Day) 2:15 Before This World - Jolly James Taylor Before This World 5:32 Springtime Heart Of The World Rani Arbo & Daisy Mayhem Violets Are Blue 3:15 poet In Addition to Faith, Hope and Pattiann Rogers (Song of the World Becoming) 3:28 Charity Slow Leonard Cohen Popular Problems 3:25 September Fields Frazey Ford Indian Ocean 3:26 Heart Is A Drum Beck Morning Phase 4:18 It`s All Okay Julia Stone By The Horns 3:57 poem The God of Prime Numbers Alice Major (Standard Candles) 0:57 poem The God of Infinities Alice Major (Standard Candles) 0:43 poem The God of Symmetry Alice Major (Standard Candles) 0:47 poem The God of Gravity Alice Major (Standard Candles) 0:24 poem The God of Salt Alice Major (Standard Candles) 0:30 poem The God of Kites and Darts Alice Major (Standard Candles) 0:34 poem The God of Automata Alice Major (Standard Candles) 0:57 Cirrus Bonobo The North Borders 0:54 poem The God of CATS Alice Major (Standard Candles) 1:38 Ocean Azam Ali & Loga R. -

Orchestral Parts

Orchestral Parts Contents Numbers ............................................................................................................................................................................ 2 A ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 B ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 7 C ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 D ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 18 E....................................................................................................................................................................................... 21 F ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 25 G ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 30 H ..................................................................................................................................................................................... -

DJ Music Catalog by Title

Artist Title Artist Title Artist Title Dev Feat. Nef The Pharaoh #1 Kellie Pickler 100 Proof [Radio Edit] Rick Ross Feat. Jay-Z And Dr. Dre 3 Kings Cobra Starship Feat. My Name is Kay #1Nite Andrea Burns 100 Stories [Josh Harris Vocal Club Edit Yo Gotti, Fabolous & DJ Khaled 3 Kings [Clean] Rev Theory #AlphaKing Five For Fighting 100 Years Josh Wilson 3 Minute Song [Album Version] Tank Feat. Chris Brown, Siya And Sa #BDay [Clean] Crystal Waters 100% Pure Love TK N' Cash 3 Times In A Row [Clean] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful Frenship 1000 Nights Elliott Yamin 3 Words Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful [Louie Vega EOL Remix - Clean Rachel Platten 1000 Ships [Single Version] Britney Spears 3 [Groove Police Radio Edit] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And A$AP #Beautiful [Remix - Clean] Prince 1000 X's & O's Queens Of The Stone Age 3's & 7's [LP] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And Jeezy #Beautiful [Remix - Edited] Godsmack 1000hp [Radio Edit] Emblem3 3,000 Miles Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful/#Hermosa [Spanglish Version]d Colton James 101 Proof [Granny With A Gold Tooth Radi Lonely Island Feat. Justin Timberla 3-Way (The Golden Rule) [Edited] Tucker #Country Colton James 101 Proof [The Full 101 Proof] Sho Baraka feat. Courtney Orlando 30 & Up, 1986 [Radio] Nate Harasim #HarmonyPark Wrabel 11 Blocks Vinyl Theatre 30 Seconds Neighbourhood Feat. French Montana #icanteven Dinosaur Pile-Up 11:11 Jay-Z 30 Something [Amended] Eric Nolan #OMW (On My Way) Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [KBCO Edit] Childish Gambino 3005 Chainsmokers #Selfie Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [Radio Edit] Future 31 Days [Xtra Clean] My Chemical Romance #SING It For Japan Michael Franti & Spearhead Feat.