Rhys Ayns Mannin 1886-1893

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

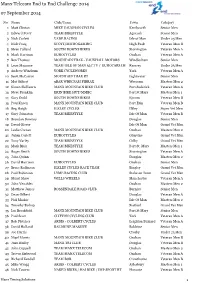

Manx Telecom End to End Challenge 2014 07 September 2014

Manx Telecom End to End Challenge 2014 07 September 2014 No Name Club/Team Town Category 1 Matt Clinton MIKE VAUGHAN CYCLES Kenilworth Senior Men 2 Edward Perry TEAM BIKESTYLE Agneash Senior Men 3 Nick Corlett VADE RACING Isle of Man Under 23 Men 4 Nick Craig SCOTT/MICROGAMING High Peak Veteran Men B 5 Steve Calland SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Storrington Veteran Men A 6 Mark Harrison EUROCYCLES Onchan Veteran Men A 7 Ben Thomas MOUNTAIN TRAX - VAUXHALL MOTORS Windlesham Senior Men 8 Leon Mazzone TEAMCYCLING ISLE TEAM OF MAN 3LC.TV / EUROCARS.IM Ramsey Under 23 Men 9 Andrew Windrum YORK CYCLEWORKS York Veteran Men A 10 Scott McCarron MOUNTAIN TRAX RT Lightwater Senior Men 11 Mat Gilbert 9BAR WRECSAM FIBRAX Wrecsam Masters Men 2 12 Simon Skillicorn MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Port Soderick Veteran Men A 13 Steve Franklin ERIN BIKE HUT/MMBC Port St Mary Masters Men 1 14 Gary Dodd SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Epsom Veteran Men B 15 Paul Kneen MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Port Erin Veteran Men B 16 Reg Haigh ILKLEY CYCLES Ilkley Super Vet Men 17 Gary Johnston TEAM BIKESTYLE Isle Of Man Veteran Men B 18 Brendan Downey Douglas Senior Men 19 David Glover Isle Of Man Grand Vet Men 20 Leslie Corran MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Onchan Masters Men 2 21 Julian Corlett EUROCYCLES Glenvine Grand Vet Men 22 Tony Varley TEAM BIKESTYLE Colby Grand Vet Men 23 Mark Blair TEAM BIKESTYLE Port St. Mary Masters Men 1 24 Roger Smith SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Storrington Veteran Men A 25 John Quinn Douglas Masters Men 2 26 David Harrison EUROCYCLES Onchan Senior Men 27 Bruce Rollinson ILKLEY CYCLES RACE -

Manx Farming Communities and Traditions. an Examination of Manx Farming Between 1750 and 1900

115 Manx Farming Communities and Traditions. An examination of Manx farming between 1750 and 1900 CJ Page Introduction Set in the middle of the Irish Sea, the Isle of Man was far from being an isolated community. Being over 33 miles long by 13 miles wide, with a central mountainous land mass, meant that most of the cultivated area was not that far from the shore and the influence of the sea. Until recent years the Irish Sea was an extremely busy stretch of water, and the island greatly benefited from the trade passing through it. Manxmen had long been involved with the sea and were found around the world as members of the British merchant fleet and also in the British navy. Such people as Fletcher Christian from HMAV Bounty, (even its captain, Lieutenant Bligh was married in Onchan, near Douglas), and also John Quilliam who was First Lieutenant on Nelson's Victory during the Battle of Trafalgar, are some of the more notable examples. However, it was fishing that employed many Manxmen, and most of these fishermen were also farmers, dividing their time between the two occupations (Kinvig 1975, 144). Fishing generally proved very lucrative, especially when it was combined with the other aspect of the sea - smuggling. Smuggling involved both the larger merchant ships and also the smaller fishing vessels, including the inshore craft. Such was the extent of this activity that by the mid- I 8th century it was costing the British and Irish Governments £350,000 in lost revenue, plus a further loss to the Irish administration of £200,000 (Moore 1900, 438). -

Manx Gaelic and Physics, a Personal Journey, by Brian Stowell

keynote address Editors’ note: This is the text of a keynote address delivered at the 2011 NAACLT conference held in Douglas on The Isle of Man. Manx Gaelic and physics, a personal journey Brian Stowell. Doolish, Mee Boaldyn 2011 At the age of sixteen at the beginning of 1953, I became very much aware of the Manx language, Manx Gaelic, and the desperate situation it was in then. I was born of Manx parents and brought up in Douglas in the Isle of Man, but, like most other Manx people then, I was only dimly aware that we had our own language. All that changed when, on New Year’s Day 1953, I picked up a Manx newspaper that was in the house and read an article about Douglas Fargher. He was expressing a passionate view that the Manx language had to be saved – he couldn’t understand how Manx people were so dismissive of their own language and ignorant about it. This article had a dra- matic effect on me – I can say it changed my life. I knew straight off somehow that I had to learn Manx. In 1953, I was a pupil at Douglas High School for Boys, with just over two years to go before I possibly left school and went to England to go to uni- versity. There was no university in the Isle of Man - there still isn’t, although things are progressing in that direction now. Amazingly, up until 1992, there 111 JCLL 2010/2011 Stowell was no formal, official teaching of Manx in schools in the Isle of Man. -

NEWSLETTER Winter 2013 Editor – Douglas Barr-Hamilton

NEWSLETTER Winter 2013 Editor – Douglas Barr-Hamilton Melodious Mhelliah Our annual Mhelliah thanksgiving service was held on Monday 7th October at St. Bride's Church, Fleet Street. Twenty-nine members and friends attended but, greatly missed, was MC and Treasurer Sam Weller and his wife Mary who had been called away to give help to family in-laws that were unwell. But very welcome back among us was Rose Fowler and Wendy who was on holiday from work. Terence and Christine Brack had come from the Island and some familiar faces like Margaret Hunt (who had been with us on Tynwald Day), Voirry and Robin Carr from Oxford, the Moore twins, Margaret and Maureen who grew up in Peel and Maureen Lomas brought a friend from South Africa. Sam, with his usual efficiency, had sent us a tick list of duties which Alastair, Stewart and Douglas were attending to when we arrived. We were welcomed by Alastair, our President, and the service was taken by past Bishop of Sodor and Mann, the Right Reverend Graeme Knowles. He drew our attention to the bidding prayer written by Bishop Wilson (1698-1755) who was also responsible for the act of worship before the herring fleet set out for a night's fishing. He spoke of each one of us being a walking harvest festival, possessing individual gifts and talents given by God of which we are stewards and need to react to throughout our lives. Our Island heritage was also one of God's gifts for which we give heartfelt thanks. There followed Maisie's wonderful recitation of the Lord's Prayer (Padiyr y Dhirn) in Manx and Margaret Brady played all our favourite harvest hymns leading us so well that Bishop commended us for our singing. -

Buchan School Magazine 1971 Index

THE BUCHAN SCHOOL MAGAZINE 1971 No. 18 (Series begun 195S) CANNELl'S CAFE 40 Duke Street - Douglas Our comprehensive Menu offers Good Food and Service at reasonable prices Large selection of Quality confectionery including Fresh Cream Cakes, Superb Sponges, Meringues & Chocolate Eclairs Outside Catering is another Cannell's Service THE BUCHAN SCHOOL MAGAZINE 1971 INDEX Page Visitor, Patrons and Governors 3 Staff 5 School Officers 7 Editorial 7 Old Students News 9 Principal's Report 11 Honours List, 1970-71 19 Term Events 34 Salvete 36 Swimming, 1970-71 37 Hockey, 1971-72 39 Tennis, 1971 39 Sailing Club 40 Water Ski Club 41 Royal Manx Agricultural Show, 1971 42 I.O.M, Beekeepers' Competitions, 1971 42 Manx Music Festival, 1971 42 "Danger Point" 43 My Holiday In Europe 44 The Keellls of Patrick Parish ... 45 Making a Fi!m 50 My Home in South East Arabia 51 Keellls In my Parish 52 General Knowledge Paper, 1970 59 General Knowledge Paper, 1971 64 School List 74 Tfcitor THE LORD BISHOP OF SODOR & MAN, RIGHT REVEREND ERIC GORDON, M.A. MRS. AYLWIN COTTON, C.B.E., M.B., B.S., F.S.A. LADY COWLEY LADY DUNDAS MRS. B. MAGRATH LADY QUALTROUGH LADY SUGDEN Rev. F. M. CUBBON, Hon. C.F., D.C. J. S. KERMODE, ESQ., J.P. AIR MARSHAL SIR PATERSON FRASER. K.B.E., C.B., A.F.C., B.A., F.R.Ae.s. (Chairman) A. H. SIMCOCKS, ESQ., M.H.K. (Vice-Chairman) MRS. T. E. BROWNSDON MRS. A. J. DAVIDSON MRS. G. W. REES-JONES MISS R. -

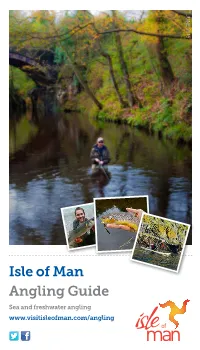

Isle of Man Angling Guide

JUNE 2015 JUNE Isle of Man Angling Guide Sea and freshwater angling www.visitisleofman.com/angling Gone fishing With fast flowing streams, well-stocked reservoirs and an incredibly accessible coastline the Isle of Man provides a perfect place to fish. Located in the path of the Gulf Stream the Island enjoys mild temperatures and attracts an abundance of marine life associated with the warm-water current. So, whether you’re a keen angler, or a novice wanting to while away a few hours, you’ll find a range of locations for both freshwater and sea fishing. And if you’re looking for something different why not charter a boat and turn your hand to deep sea fishing where you can try your luck at catching crabs, lobster and even shark? What you can catch A taster of what you could catch during your visit to the Island: Rock fishing: coalfish, pollack, ballan wrasse, cuckoo wrasse, grey mullet, mackerel, conger eel Breakwater fishing: coalfish, pollack, ballan wrasse, cuckoo wrasse, grey mullet, mackerel, conger eel Harbour fishing: grey mullet, coalfish, flounder Shore fishing: bass, tope, dogfish, grey mullet, mackerel, coalfish, plaice, dab Freshwater fishing: brown trout, sea trout, Atlantic salmon, rainbow trout, eels Photography by Mark Boyd and James Cubbon 3 Sea angling 4 With almost 100 miles of coastline you’ll have no trouble Bride finding a harbour, breakwater or rugged rock formation from which to cast off. Andreas Jurby Between April and September is the prime time for sea fishing with the plankton population blooming in the warmer months. This attracts sand eels, vast shoals of St Judes 2 16 mackerel, grey mullet, pollack and cod. -

Manx Place-Names: an Ulster View

37 Manx Place-Names: an Ulster View Kay Muhr In this chapter I will discuss place-name connections between Ulster and Man, beginning with the early appearances of Man in Irish tradition and its association with the mythological realm of Emain Ablach, from the 6th to the I 3th century. 1 A good introduction to the link between Ulster and Manx place-names is to look at Speed's map of Man published in 1605.2 Although the map is much later than the beginning of place-names in the Isle of Man, it does reflect those place-names already well-established 400 years before our time. Moreover the gloriously exaggerated Manx-centric view, showing the island almost filling the Irish sea between Ireland, Scotland, England and Wales, also allows the map to illustrate place-names from the coasts of these lands around. As an island visible from these coasts Man has been influenced by all of them. In Ireland there are Gaelic, Norse and English names - the latter now the dominant language in new place-names, though it was not so in the past. The Gaelic names include the port towns of Knok (now Carrick-) fergus, "Fergus' hill" or "rock", the rock clearly referring to the site of the medieval castle. In 13th-century Scotland Fergus was understood as the king whose migration introduced the Gaelic language. Further south, Dundalk "fort of the small sword" includes the element dun "hill-fort", one of three fortification names common in early Irish place-names, the others being rath "ring fort" and lios "enclosure". -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

Report of the Select Committee on the Registration of Land (Petition for Redress)

PP 2016/0078 REPORT OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE REGISTRATION OF LAND (PETITION FOR REDRESS) 2015-16 REPORT OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE REGISTRATION OF LAND (PETITION FOR REDRESS) On Wednesday 21st October 2015 it was resolved – That a committee of three Members be appointed with powers to take written and oral evidence pursuant to sections 3 and 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1876, as amended, to consider and to report to Tynwald by June 2016 on the Petition for Redress of John Ffynlo Craine and Annie Andrée Jeannine Hommet presented at St John’s on 6th July 2015 in relation to the registration of property. The powers, privileges and immunities relating to the work of a committee of Tynwald are those conferred by sections 3 and 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1876, sections 1 to 4 of the Privileges of Tynwald (Publications) Act 1973 and sections 2 to 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1984. Committee Membership Mr M R Coleman MLC (Chair) Mr G G Boot MHK (Glenfaba) Mr A L Cannan MHK (Michael) Copies of this Report may be obtained from the Tynwald Library, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas IM1 3PW (Tel 01624 685520, Fax 01624 685522) or may be consulted at www.tynwald.org.im All correspondence with regard to this Report should be addressed to the Clerk of Tynwald, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas IM1 3PW. Table of Contents I. THE COMMITTEE AND THE INVESTIGATION ................................................... 1 II. BACKGROUND: THE REGISTRATION OF LAND IN THE ISLE OF MAN ................. 2 III. THE PETITION AND THE PETITIONERS’ PROPOSALS FOR REFORM .................. -

Fíanaigecht in Manx Tradition FÍANAIGECHT in MANX TRADITION 1

Fíanaigecht in Manx Tradition FÍANAIGECHT IN MANX TRADITION 1 GEORGE BRODERICK University of Mannheim Introduction: The Finn Cycle In order to set the Manx examples of Fíanaigecht in context I cite here Bernhard Maier's short sketch of the Finn Cycle as it appears in Maier (1998: 118). Finn Cycle or Ossianic Cycle. The prose naratives and ballads centred upon the legendary hero Finn mac Cumaill and his retinue, the Fianna. They are set in the time of the king Cormac mac Airt at the beginning of the 3rdC AD. The heroes, apart from Finn, the leader of the Fianna, are his son Oisín, his grandson Oscar, and the warriors Caílte mac Rónáin, Goll mac Morna and Lugaid Lága. Most of the stories concerning F[inn] are about hunting adventures, love-affairs [...] and military disputes [...]. The most substantial work of this kind, combin- ing various episodes within a narrative framework, is Acallam na Senórach . The ballads concerning F[inn] gained in popularity from the later Middle Ages onwards and were the most important source of James Mac- pherson's "Works of Ossian" (Maier 1998: 118). The individual texts of the poems and ballads concerned with the Finn Cycle seemingly date over a period from the learned scribal tradition of the eleventh 2 to the later popular oral tradition of the early seventeenth century. Sixty-nine poems from this corpus survive in a single manuscript dating from 1626-27 known as Duanaire Finn ('Finn's poem book') (cf. Mac Neill 1908, Murphy 1933, 1953, Carey 2003). According to Ruairí Ó hUiginn (2003: 79), Duanaire Finn forms part of a long manuscript that was compiled in Ostend in 1626-7. -

The Irish Language and the Irish Legal System:- 1922 to Present

The Irish Language and The Irish Legal System:- 1922 to Present By Seán Ó Conaill, BCL, LLM Submitted for the Award of PhD at the School of Welsh at Cardiff University, 2013 Head of School: Professor Sioned Davies Supervisor: Professor Diarmait Mac Giolla Chríost Professor Colin Williams 1 DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… 2 STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed ………………………………………… -

IOMFHS Members' Interests Index 2017-2020

IOMFHS Members’ Interests Index 2017-2021 Updated: 9 Sep 2021 Please see the relevant journal edition for more details in each case. Surnames Dates Locations Member Journal Allen 1903 08/9643 2021.Feb Armstrong 1879-1936 Foxdale,Douglas 05/4043 2018.Nov Bailey 1814-1852 Braddan 08/9158 2017.Nov Ball 1881-1947 Maughold 02/1403 2021.Feb Banks 1761-1846 Braddan 08/9615 2020.May Barker 1825-1897 IOM & USA 09/8478 2017.May Barton 1844-1883 Lancs, Peel 08/8561 2018.May Bayle 1920-2001 Douglas 06/6236 2019.Nov Bayley 1861-2007 08/9632 2020.Aug Beal 09/8476 2017.May Beck ~1862-1919 Braddan,Douglas 09/8577 2018.Nov Beniston Leicestershire 08/9582 2019.Aug Beniston c.1856- Leicestershire 08/9582 2020.May Blanchard 1867 Liverpool 08/8567 2018.Aug Blanchard 1901-1976 08/9632 2020.Aug Boddagh 08/9647 2021.Jun Bonnyman ~1763-1825 02/1389 2018.Aug Bowling ~1888 Douglas 08/9638 2020.Nov Boyd 08/9647 2021.Jun Boyd ~1821 IOM 09/8549 2021.Jun Boyd(Mc) 1788 Malew 02/1385 2018.Feb Boyde ~1821 IOM 09/8549 2021.Jun Bradley -1885 Douglas 09/8228 2020.May Breakwell -1763 06/5616 2020.Aug Brew c.1800 Lonan 09/8491 2018.May Brew Lezayre 06/6187 2018.May Brew ~1811 08/9566 2019.May Brew 08/9662 2021.Jun Bridson 1803-1884 Ramsey 08/9547 2018.Feb Bridson 1783 Douglas 08/9547 2018.Feb Bridson c.1618 Ballakew 08/9555 2018.May Bridson 1881 Malew 08/8569 2018.Nov Bridson 1892-1989 Braddan,Massachusetts 09/8496 2018.Nov Bridson 1861 on Castletown, Douglas 08/8574 2018.Nov Bridson ~1787-1812 Braddan 09/8521 2019.Nov Bridson 1884 Malew 06/6255 2020.Feb Bridson 1523- 08/9626