<I>Maybe Mermaids and Robots Are Lonely: 40 Stories and a Novella</I>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastmont High School Items

TO: Board of Directors FROM: Garn Christensen, Superintendent SUBJECT: Requests for Surplus DATE: June 7, 2021 CATEGORY ☐Informational ☐Discussion Only ☐Discussion & Action ☒Action BACKGROUND INFORMATION AND ADMINISTRATIVE CONSIDERATION Staff from the following buildings have curriculum, furniture, or equipment lists and the Executive Directors have reviewed and approved this as surplus: 1. Cascade Elementary items. 2. Grant Elementary items. 3. Kenroy Elementary items. 4. Lee Elementary items. 5. Rock Island Elementary items. 6. Clovis Point Intermediate School items. 7. Sterling Intermediate School items. 8. Eastmont Junior High School items. 9. Eastmont High School items. 10. Eastmont District Office items. Grant Elementary School Library, Kenroy Elementary School Library, and Lee Elementary School Library staff request the attached lists of library books be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. Sterling Intermediate School Library staff request the attached list of old social studies textbooks be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. Eastmont Junior High School Library staff request the attached lists of library books and textbooks for both EJHS and Clovis Point Intermediate School be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. Eastmont High School Library staff request the attached lists of library books for both EHS and elementary schools be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. ATTACHMENTS FISCAL IMPACT ☒None ☒Revenue, if sold RECOMMENDATION The administration recommends the Board authorize said property as surplus. Eastmont Junior High School Eastmont School District #206 905 8th St. NE • East Wenatchee, WA 98802 • Telephone (509)884-6665 Amy Dorey, Principal Bob Celebrezze, Assistant Principal Holly Cornehl, Asst. -

Shadowrun Changeling SR6

CHANGELING IN THE 6TH WORLD Version 1.1 by Ed “Runner Smurf” Pichon INTRODUCTION This is a writeup on how to use the old WhiteWolf Changeling setting and characters in Shadowrun. This writeup is updated for Shadowrun 6th Edition. I have often thought that the themes of Changeling, my favorite World of Darkness game, corresponded quite well with the Shadowrun campaign setting - faerie tales, ancient magics re- turned, corrupted innocence, struggling against an oppressive world. The Court of Shadows book, while an interest- ing attempt to bring more faerie tale elements into Shadowrun, didn’t quite do enough for me. After some experi- ments in my own games, I have found that bringing Changeling into can work quite well. Inspired by the release of the Changeling 20th Anniversary Edition, I have decided to revise and codify my house rules for bringing kithain into the 6th World. This writeup attempts to give some guidance on how to do it, and give ideas for addressing the technical questions. I suspect that there aren’t a lot of people who know and love both games, but for those of you that do, hopefully this will be useful to you. This is aimed at SR 6th Edition. I will be updating frequently as I get used to how 6th edition works, and have some practical experience in my games. Many thanks to the folks that put together the Changeling 20th Anniversary Edition (C20) - it’s a fantastic book, and a great compilation of all that has been put together for Changeling over the years, with some good updates. -

Monsters by Type Type CR Type CR Type CR Type CR Aberration Spider, Red-Banded Line

TOME OF BEASTS MONSTERS BY TYPE Type CR Type CR Type CR Type CR Aberration Spider, Red-Banded Line .... 1/4 Tophet ................................... 8 Liosalfar ................................. 8 Arboreal Grappler ...................3 Spider, Sand ............................7 Ushabti .................................. 9 Rime Worm, Adult ................. 6 Asanbosam ..............................5 Suturefly ............................ 1/4 Witchlight .......................... 1/4 Rime Worm, Grub ...................1 Bagiennik ................................3 Swarm of Prismatic Beetles ......3 Xanka................................. 1/4 Sathaq Worm ....................... 10 Chelicerae ...............................7 Titanoboa .............................12 Dragon Slow Storm ............................ 15 Dorreq ................................... 4 War Ostrich ........................ 1/2 Dragon Eel ...........................12 Spark ......................................7 Eater of Dust .......................... 9 Wharfling ............................ 1/8 Dragon, Cave, Adult ..............16 Swarm of Fire Dancers ............7 Fate Eater ............................... 6 Wharfling, Swarm .................. 4 Dragon, Cave, Wyrmling ........ 2 Thuellai ................................ 10 Mamura ..................................5 Ychen Bannog ....................... 11 Dragon, Cave, Young .............. 8 Fey Mimic, Map ....................... 1/4 Celestial Dragon, Flame Adult .............16 Abominable Beauty .............. -

Fiction) Anderson, Kevin J

Abbott, Karen Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy Abe, Shana Queen of Dragons Abe, Shana The Dream Thief Abe, Shana The Smoke Thief Achebe, Chinua Things Fall Apart Adams, Doug The Restaurant at the End of the Universe Adams, Richard Watership Down Adcock, Thomas Dark Maze Adler, Elizabeth The Property of a Lady Ahern, Cecelia If you could See Me Now Akst, Daniel St. Burl's Obituary Albee, Edward Who's Afraid of Virginia Wolf Albom, Mitch For One More Day Albom, Mitch The Five People You Meet in Heaven (2) Albom, Mitch The Time Keeper Alcott, Louisa May Little Women (One In House) (2) Alexander, Bruce Blind Justice Alison, Jane The Love Artist Allen, Dwight Judge Allende, Isabel Daughter of Fortune Allende, Isabel Portrait in Sepia Allende, Isabel Zorro Allison, Dorothy Bastard out of Carolina Alvarez, Julia How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents Amory, Cleveland The Cat and the Curmudgeon Amory, Cleveland The Cat Who Came for Christmas Anaya, Rudolfo Bless Me, Ultima Anderson, Catherine Comanche Magic Anderson, Catherine Comanche Moon Anderson, Catherine Morning Light Anderson, Kent Night Dogs Anderson, Kevin J. Hidden Empire (Sci Fi) Anderson, Kevin & Doug Beason Lethal Exposure (Sci Fi) Anderson, Kevin J. Of Fire and Night (Science Fiction) Anderson, Kevin J. Scattered Suns (Science Fiction) Anderson, Susan Baby Don't Go Andreas, Steve Is There Life Before Death? Anderson, Susan Getting Lucky Andrews, Mary Kay Blue Christmas (large print) Andrews, V.C. Delia's Crossing Ansay, A. Manette Vinegar Hill Archer, Jeffrey A Matter of Honor Archer, -

Changeling Mechanics Packet Contents Introduction Chapter 1: Tempers, Seemings, Traits, Etc

Changeling Mechanics Packet Contents Introduction Chapter 1: Tempers, Seemings, Traits, Etc. Chapter 2: Birthrights, Frailties, Boons, Flaws Chapter 3: Merits and Flaws Chapter 4: Realms Chapter 5: Arts Chapter 6: Bunks Chapter 7: Treasures and Inanimate Chimera Chapter 8: New Art Guidelines Chapter 9: Legendary Magic 1 Introduction: Unlike Werewolf and Vampire, Changeling received little in the way of Revised support and never received updated rules from the original printing. The two LARP books (Shining Host and the Shining Host Players Guide) stand among the most confusing and poorly written texts among MET regarding mechanics. The goal of this packet is to serve as a revised set of rules for Changeling-specific mechanics to be used as a baseline for the Org. While it is non-binding, it is strongly recommended that games wishing to employ changelings (either as prime genre or in addition to other genres) use these rules *particularly in regards to Arts and Realms* as a baseline, employing perhaps limited house rules from there. This packet includes many house rules and translations from various games around the org (borrowed with permission) and is by no means a singular effort. It also includes several optional rules for chronicles to customize their preferences, as well as frequently requested guidelines for things like adjudicating treasures. Finally, it also includes some original content for games to use if they so wish. Throughout the work, the author will seek to describe the reasons behind the material presented and the philosophy governing the recommendations. Chapter 1: Tempers, Seemings, Traits, Etc. Traits and tempers are among the most significant aspects of any MET rules set. -

The Mermaid Series Thomas Hey Wood

THE MERMAID SERIES THOMAS HEY WOOD LONDON ERNEST BENN, LTD. THE MERMAID SERIES THOMAS HEYWOOD EDITED BY A. WILSON VERITY WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY J. ADDINGTON SYMONDS •1 lie and dream of your full mermaid wine."—Beawnoni. LONDON ERNEST BENN LIMITED NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS " What things have we seen Done at the Memtiaid ! heard words that have been So nimble, and so full of subtle flame, As if that every one from whence they c&me Had meant to put his whole wit in a jest, i\nd had resolved to live a fool the rest Of his duU life." Master Francis Beaurmmt to Ben fonson. •* Souls of Poets dead and gone, What Elysium have ye known, Happy field or mossy cavern, Choicer than the Mermaid Tavern ?"' Kmts. Pritiied in Great Britain PAGE THOMAS HEYWOOD. ........ vii A WOMAN KILLED WITH KINDNESS i THE FAIR MAID OF THE WEST .75 THE ENGLISH TRAVELLER. .151 THE WISE WOMAN OF HOGSDON 249 THE RAPE OF LUCRECE 327 The world's a theatre, the earth a stage, * Which God and nature doth with actors fill: Kings have their entrance in due equipage, And some their parts play well, and others ill. The best no better are (in this thedtre), Where every humour's fitted in his kind ; This a true subject acts, and that a traitor, The first applauded, and the last confined ; This plays an honest man, and that a knave, A gentle person this, and he a clown, One man is ragged, and another brave : All men have parts, and each one acts his own. -

1457878351568.Pdf

— Credits — Authors: Patrick Sweeney, Sandy Antunes, Christina Stiles, Colin Chapman, and Robin D. Laws Additional Material: Keith Sears, Nancy Berman, and Spike Y Jones Editor: Spike Y Jones Index: Janice M. Sellers Layout and Graphic Design: Hal Mangold Cover Art: Patricia Ann Lewis-MacDougall Interior Art: Janet Chui, Patricia Ann Lewis-MacDougall and Jennifer Meyer Playtesters: Elizabeth, Joey, Kathryn, Lauren, Ivy, Kate, Miranda, Mary, Michele, Jennifer, Rob, Bethany, Jacob, John, Kelly, Mark, Janice, Anne, and Doc Special Thanks To: Mark Arsenault, Elissa Carey, Robert “Doc” Cross, Darin “Woody” Eblom, Larry D. Hols, Robin D. Laws, Nicole Lindroos, David Millians, Rob Miller, Liam Routt, and Chad Underkoffler If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales. —Albert Einstein Copyright 2007 by Firefly Games. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention. Faery’s Tale and all characters and their likenesses are trademarks owned by and/or copyrights by Firefly Games. All situations, incidents and persons portrayed within are fictional and any similarity without satiric intent to individuals living or dead is strictly coincidental. Designed and developed by Firefly Games, 4514 Marconi Ave. #3, Sacramento CA 95821 [email protected] Visit our website at www.firefly-games.com. Published by Green Ronin Publishing 3815 S. Othello St. Suite 100, #304, Seattle, WA 98118 [email protected] Visit our website at www.greenronin.com. Table of Contents Preface .........................................................................3 A Sprite’s Tale .......................................................49 A Pixie’s Tale .............................................................4 Faery Princesses & Magic Wands ............51 Introduction ................................................................7 Titles .................................................... -

Université Du Québec Mémoire Présenté À L'université Du

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ À L'UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À TROIS-RIVIÉRES COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAITRISE EN LETTRES PAR AUDREY BOULANGER MYTHOLOGIE CELTE ET ESTHÉTIQUE DU VERTIGE DANS L'ŒUVRE DE LÉA SILHOL AVRIL 2012 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Héritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-88963-3 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-88963-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, télécommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protégé cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. without the author's permission. -

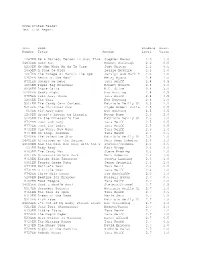

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1087EN Be a Perfect Person in Just Thre Stephen Manes 1.0 1.0 34830EN Home Run Robert Burleigh 2.0 0.5 5236EN My Mom Made Me Go To Camp Judy Delton 2.1 0.5 1055EN A Bone to Pick Leslie McGuire 2.3 1.0 1267EN The Escape of Marvin the Ape Caralyn and Mark B 2.3 1.0 6352EN Beans on the Roof Betsy Byars 2.4 1.0 8721EN Hungry No More Tana Reiff 2.4 0.5 1265EN Paper Bag Princess Robert Munsch 2.4 1.0 8238EN Phone Calls R.L. Stine 2.4 3.0 10202EN Smoky Night Eve Bunting 2.4 0.5 8795EN Take Away Three Tana Reiff 2.4 0.5 1266EN The Wall Eve Bunting 2.4 1.0 5211EN The Candy Corn Contest Patricia Reilly Gi 2.5 1.0 5216EN The Christmas Coat Clyde Robert Bulla 2.5 0.5 910EN Fly Away Home Eve Bunting 2.5 0.5 1259EN Grace's Letter to Lincoln Peter Pupp 2.5 2.0 5225EN In the Dinosaur's Paw Patricia Reilly Gi 2.5 1.0 8769EN Juan and Lucy Tana Reiff 2.5 0.5 8770EN Just for Today Tana Reiff 2.5 0.5 8732EN Old Ways, New Ways Tana Reiff 2.5 1.0 8737EN So Long, Snowman Tana Reiff 2.5 0.5 5246EN The Valentine Star Patricia Reilly Gi 2.5 1.0 14651EN Afternoon on the Amazon Mary Pope Osborne 2.6 1.0 43508EN And the Dish Ran Away with the S Stevens/Crummel 2.6 0.5 937EN Baby Baby Paul Kropp 2.6 2.0 8703EN The Candy Man Steve Bradley 2.6 1.0 6311EN Dinosaurs Before Dark Mary Osborne 2.6 1.0 8713EN Escape from Tomorrow Sereta Lanning 2.6 1.0 6361EN Fourth Grade Rats Jerry Spinelli 2.6 2.0 8779EN Mollie's -

'Fairy' in Middle English Romance

'FAIRY' IN MIDDLE ENGLISH ROMANCE Chera A. Cole A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2014 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/6388 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence ‘FAIRY’ IN MIDDLE ENGLISH ROMANCE Chera A. Cole A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the School of English in the University of St Andrews 17 December 2013 i ABSTRACT My thesis, ‘Fairy in Middle English romance’, aims to contribute to the recent resurgence of interest in the literary medieval supernatural by studying the concept of ‘fairy’ as it is presented in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Middle English romances. This thesis is particularly interested in how the use of ‘fairy’ in Middle English romances serves as an arena in which to play out ‘thought-experiments’ that test anxieties about faith, gender, power, and death. My first chapter considers the concept of fairy in its medieval Christian context by using the romance Melusine as a case study to examine fairies alongside medieval theological explorations of the nature of demons. I then examine the power dynamic of fairy/human relationships and the extent to which having one partner be a fairy affects these explorations of medieval attitudes toward gender relations and hierarchy. The third chapter investigates ‘fairy-like’ women enchantresses in romance and the extent to which fairy is ‘performed’ in romance. -

By Dan Dillon, Chris Harris, Rodrigo Garcia Carmona, and Wolfgang

by Dan Dillon, Chris Harris, Rodrigo Garcia Carmona, and Wolfgang Baur SampleDeveloped by Steven Winter file TOME OF BEASTS CREDITS Design: Dan Dillon, Chris Harris, Cover Art: Marcel Mercado Rodrigo Garcia Carmona, and Wolfgang Baur Art Director: Marc Radle Additional Design: William Ryan Carden, Layout and Graphic Design: Marc Radle Christopher Carlson, Michael John Conard, James L. Crawford, Christopher Delvo, Matthew F. Dowd, Artists: Darren Calvert, Ivan Lee Dixon, Micah Epstein, Timothy Eagon, Matthew Eyman, Robert Fairbanks, Frank Garza, Felipe Gaona, Josh Hass, Ambrose H. Hoilman, David Gibson, Christopher Gilliford, John Henzel, Michael Jaecks, Eoghan Kerrigan, Guido Kuip, Pat Loboyko, Jeremy Hochhalter, Michael Holland, Ben Iglauer, Shawncee McCoy, Dio Mahesa, Justin Mayhew, James Introcaso, Dan Layman-Kennedy, Christopher Lockey, Marcel Mercado, Aaron Miller, Johnny Morrow, Maximilian Maier, Greg Marks, Dave Olson, Richard Pratt, Jason Rainville, Felipe Gaona Reydet, Kathryn Steele, Marc Radle, Jon Sawatsky, Ryan Shatford, Troy E. Taylor, Florian Stitz, Nakarin Sukontakorn, Andrew Teheran, Jorge A. Torres, Darius Uknuis, Ørjan Ruttenborg Svendsen, Byran Syme, Cory Trego-Erdner, Sersa Victory, and Ben Wertz Eva Widermann, and Keiran Yanner Development: Steven Winter Logo: Doug Wohlfeil Editing: Peter Hogan, Wade Rockett, and Wolfgang Baur Playtest Coordinator: Ben McFarland Proofreading: Dan Dillon Playtesters: Aaron Meadows, Aaron Sarver, Adam Sirois, Al Lencioni, Gregory Blair, Guillaume Berthome, Guy Parisi, Church, Alex -

Gnomes and Imps: the Mythology of Brownies

Gnomes and Imps: The Mythology of Brownies by Nicola Higgins 1 Co Contents Introduction 3 Brownies 4 Gnomes 5 Imps 6 Elves 7 Pixies 8 Sprites 9 Leprechauns 10 Ghillie Dhu 11 Kelpies 12 Bwbachod 13 Bibliography 14 2 Introduction "What I am going to do?" their mother sighed. "I can't keep the cottage tidy. If only we had a Brownie!" " What's a Brownie?" asked Tommy. "A Brownie is a magical little creature, which slips into houses very early before anyone is awake. It tidies toys, irons clothes, washes dishes and does all sorts of helpful things in secret," replied his mother. From The Brownie Story As many seven, eight and nine year-olds across the country could tell you, Brownies are magical little creatures, which come in the night and do secret good turns. They don’t ask for thanks or praise, they don’t expect payment. They simply come, do some chore that has been left undone, and then vanish to wherever they came from. But what else do we know about them? And what about Imps, Elves and Pixies? Gnomes, Sprites, and Ghillie Dhu? Not to mention Leprechauns, Kelpies and Bwbachod? This book tells stories of the hidden races. Imps at play, and Gnomes at work, Irish Leprechauns with their pots of gold and Scottish Kelpies who live in rivers and lakes. Read on and discover a whole new world! 3 Brownies The Brownie is a household creature. They are generally live in country houses, but have been known to appear in the city. They are friendly towards humans – though adults never see them.