Kelley Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vietnamrejsen - Februar 2014

Vietnamrejsen - februar 2014 Travel Report concerning ”Lotuslandet – 18 days cultural tour in Vietnam” Tour Guide: Martin Smedebøl, writer of this report. Time: February 2. – 19. 2014. Meeting the group in Kastrup Airport: 2 persons arrived 40 minutes late due to late arriving train from Jylland. 2 ladies travelling together were booked as double room, but they needed twin beds (should have been noted on the rooming lists). Air transportation: international transportation with Turkish Airlines (Boeing 777), and 2 domestic flights with Vietnam Airlines (Airbus 320). Group reservation always gives some problems with seating. All flights were done according to plan and on time. All luggages arrived on time. OBS: Our flight had an intermediate stop in Bangkok, which surprised the participants – it should have been mentioned in the letter of departure! Local transportations in Vietnam: all buses and drivers were good. Night train from Hanoi to Dong Hoi were OK (a myriad of Vietnamese travelers slept on the floors in the corridors due to Tet). It is not optimal to arrive in Dong Hoi at 4.40 a.m. – a later arrival would be better! The hotel boat in Halong Bay was not big enough for our group – a second boat was needed, and 4 passengers had to climb between the boats, when they went to sleep. Hotels in Vietnam: all hotels were OK, but Asian Ruby 3 in Saigon had not enough capacity for breakfast for 33 pax ++. Medaillion Hotel in Hanoi was charming and good situated. Moonlight Hotel in Hué was very new, good and with a nice restaurant at the top floor. -

Chinese Dress: from the Qing Dynasty to the Present by Valery Garrett

Chinese Dress: From The Qing Dynasty To The Present By Valery Garrett If searched for the ebook Chinese Dress: From the Qing Dynasty to the Present by Valery Garrett in pdf form, then you have come on to the loyal site. We presented utter variant of this book in doc, DjVu, PDF, txt, ePub forms. You may read Chinese Dress: From the Qing Dynasty to the Present online by Valery Garrett either load. Withal, on our site you can read guides and another artistic eBooks online, or downloading them. We like to draw your consideration that our website not store the book itself, but we give reference to the website where you can downloading or reading online. If you have necessity to downloading Chinese Dress: From the Qing Dynasty to the Present pdf by Valery Garrett, then you have come on to the correct site. We have Chinese Dress: From the Qing Dynasty to the Present doc, PDF, ePub, txt, DjVu formats. We will be glad if you go back more. qing dynasty - wikipedia, the free encyclopedia - the Han Chinese Qing army led by the Han Chinese Ming defector Liu Liangzuo ( ), whereas Han officials wore clothing with a square emblem. chinese dress : from the qing dynasty to the - Author/Creator Garrett, Valery M., 1942-Language English. Imprint Tokyo ; Rutland, Vt. : Tuttle Pub., c2007. Physical description 240 p. : ill. (some col.) ; 32 cm. fashion timeline of chinese women clothing - dress,China Clothing,Women Clothing, , ,clothing,Fashion Timeline of Chinese Women Clothing Qing Dynasty. When China fell under Manchurian valery garrett | zoominfo.com - Malaysia and Han Wei Lin from Singapore who each receive a copy each of Valery Garrett's new book She lectures on Chinese culture in Hong Kong and chinese dress in the qing dynasty-006 chinese - Chinese dress in the qing dynasty,Chinese dress in the qing dynasty . -

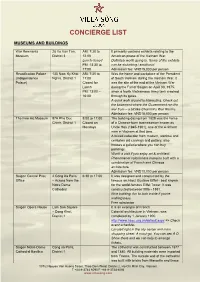

Concierge List

CONCIERGE LIST MUSEUMS AND BUILDINGS War Remnants 28 Vo Van Tan, AM: 7:30 to It primarily contains exhibits relating to the Museum District 3 12:00 American phase of the Vietnam War. Lunch closed Definitely worth going to. Some of the exhibits PM: 13:30 to can be disturbing / emotional. 17:00 Admission fee: VND15,000 per person Reunification Palace 135 Nam Ky Khoi AM: 7:30 to Was the home and workplace of the President (Independence Nghia, District 1 11:00 of South Vietnam during the Vietnam War. It Palace) Closed for was the site of the end of the Vietnam War Lunch during the Fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, PM: 13:00 – when a North Vietnamese Army tank crashed 16:00 through its gates. A quick walk around is interesting. Check out the basement where the Government ran the war from – a bit like Churchill’s War Rooms. Admission fee: VND15,000 per person The Fine Art Museum 97A Pho Duc 9:00 to 17:00 The building dating from 1829 was the home Chinh, District 1 Closed on of a Chinese-born businessman known as Mondays Uncle Hoa (1845-1901), one of the 4 richest men in Vietnam at that time. A mixed collection from modern, wartime and centuries old carvings and pottery, also houses a galleria where you can buy paintings. Worth a visit if you enjoy art & architect. Phenomenal colonial era mansion built with a combination of French and Chinese architecture Admission fee: VND10,000 per person Saigon Central Post 2 Cong Xa Paris 6:30 to 17:00 It was designed and constructed by the Office – Across from the famous architect Gustave Eiffel - best known Notre Dame for the world-famous Eiffel Tower. -

Discourse: Ethnic Identity in the ESL Classroom

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 428 578 FL 025 777 AUTHOR Allendoerfer, Cheryl TITLE Creating "Vietnamerican" Discourse: Ethnic Identity in the ESL Classroom. PUB DATE 1999-04-00 NOTE 30p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (Montreal, Canada, April 19-23, 1999). PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) -- Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Acculturation; *Asian Americans; Discourse Analysis; *English (Second Language); Ethnic Groups; *Ethnicity; Ethnography; High School Students; High Schools; Identification (Psychology); Immigrants; Limited English Speaking; *Literacy Education; Refugees; Second Language Instruction; Self Concept; Student Adjustment; *Vietnamese People ABSTRACT An ethnographic study examined how learning English and becoming more literate in the dominant discourse affects the identity or self-concept of Vietnamese immigrant students, and how new discourse may be created as students negotiate multiple literacies. It was conducted in a Seattle area high school and focused on 22 Vietnamese students in an English-as-a-Second-Language (ESL) program, all of whom had lived in the United States for one to four years. Data were gathered using observation, informal conversations, a photography and writing project undertaken with the students, and formal interviews with students, teachers, and administrators. Analysis explored several issues: how students perceived their ethnic identities; what "Americanization" means to the students, their parents, and their teachers; how definitions of the concept differ among the groups, and the conflicts that may arise therefrom; and whether immigrant students need to identify with the dominant discourse or majority culture to succeed in American schools. Results challenge the assumption that assimilation means adopting elements of the new culture alongside the native culture, and suggest that a third culture is constructed with elements resembling elements of the first two but fundamentally different from either. -

Cultural Profile Resource: Vietnamese

Cultural Profile Resource: Vietnamese A resource for aged care professionals Birgit Heaney Dip. 19/06/2016 A resource for aged care professionals Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Location and Demographic ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Everyday Life ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Family ............................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Personal Hygiene ............................................................................................................................................................ 10 Leisure and Recreation ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Religion ........................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Food and Diet ................................................................................................................................................................ -

The Vietnam-U.S. Normalization Process

Order Code IB98033 CRS Issue Brief for Congress Received through the CRS Web The Vietnam-U.S. Normalization Process Updated June 17, 2005 Mark E. Manyin Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress CONTENTS SUMMARY MOST RECENT DEVELOPMENTS BACKGROUND AND ANALYSIS U.S.-Vietnam Relations, 1975-1998 Policy Initiatives During the Carter Administration Developments During the Reagan and Bush Administrations Developments During the Clinton Administration Recent U.S.-Vietnam Relations Economic Ties — The Bilateral Trade Agreement Implementation of the BTA U.S.-Vietnam Trade Flows A Bilateral Textile Agreement Vietnam’s Bid to Join the World Trade Organization (WTO) Shrimp Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) U.S. Bilateral Economic Assistance to Vietnam Human Rights and Religious Freedom Political and Security Ties Agent Orange Human Trafficking POW/MIA Issues Vietnam’s Situation Economic Developments Political Trends The Ninth and Tenth Party Congresses Unrest in the Central Highlands Region Foreign and Defense Policy LEGISLATION IB98033 06-17-05 The Vietnam-U.S. Normalization Process SUMMARY U.S.-Vietnam diplomatic and economic the existing East Asian order. The next, and relations remained essentially frozen for more final, step toward full normalization would be than a decade after the 1975 communist vic- granting permanent normal trade relations tory in South Vietnam. Relations took major status to Vietnam. This step, which would steps forward in the mid-1990s, particularly in require congressional approval, almost cer- 1995, when the two sides opened embassies in tainly will be considered in the context of each other’s capitals. Since then, the normal- negotiating Vietnam’s accession to the World ization process has accelerated and bilateral Trade Organization (WTO). -

US-Vietnam Relations,” Paper Presented at the Future of Relations Between Vietnam and the United States, SAIS, Washington, DC, October 2-3, 2003

Order Code RL33316 U.S.-Vietnam Relations: Background and Issues for Congress Updated October 31, 2008 Mark E. Manyin Specialist in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division U.S.-Vietnam Relations: Background and Issues for Congress Summary After communist North Vietnam’s victory over U.S.-backed South Vietnam in 1975, U.S.-Vietnam relations remained essentially frozen until the mid-1990s. Since then, bilateral ties have expanded remarkably, to the point where the relationship has been virtually normalized. Indeed, since 2002, overlapping strategic and economic interests have compelled the United States and Vietnam to improve relations across a wide spectrum of issues. Congress played a significant role in the normalization process and continues to influence the state of bilateral relations. Voices favoring improved relations have included those reflecting U.S. business interests in Vietnam’s reforming economy and U.S. strategic interests in expanding cooperation with a populous country — Vietnam has over 85 million people — that has an ambivalent relationship with China. Others argue that improvements in bilateral relations should be conditioned upon Vietnam’s authoritarian government improving its record on human rights. The population of over 1 million Vietnamese Americans, as well as legacies of the Vietnam War, also drive continued U.S. interest. Economic ties are the most mature aspect of the bilateral relationship. The United States is Vietnam’s largest export market. The final step toward full economic normalization was accomplished in December 2006, when Congress passed and President Bush signed H.R. 6111 (P.L. 109-432), extending permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) status to Vietnam. -

271117Intellasia Finance Vietn

finance & business news 27 November FINANCE . 1 Vietnam, Slovakia promote trade, investment cooperation 35 Reference exchange rate goes up 1 VND at week's beginning 1 Vietnam's images, potentials spotlighted in Romania 36 Pressure on exchange rate more likely when Fed raises interest Vietnam and Poland set to tighten trade and investment rates 1 cooperation 36 Many banks have increased interest rates 3 BIZ NEWS. 37 Bad debt reduction remains insubstantial 4 Business Briefs 27 November, 2017 37 NPLs in property drop significantly 5 VN Index concludes winning week 38 Why are banks simultaneously divesting? 5 Market rally loses steam 39 Fintech a tool to boost integration: Asean meet 6 Investors warned of a likely correction 39 Foreign investors internally transfer 3 million VPBank shares 8 In new scheme, Song Da Corp IPO to offer 220m shares 40 Government reports: economy sees quality improvements 8 Online shopping platforms stir up Black Friday fever 41 Fitch forecasts high economic growth rate for Vietnam 9 Vietnam among countries hardest-hit by cyber crime 42 Vietnam to lose over 110 trillion dong due to free trade in Great expectations 43 next 3 years 10 Proptech to alter real estate industry 45 National Assembly wrapped up with big laws 10 HN, HCM City asked to report apartment disputes 46 Law on public debt management passed 11 Few enterprises keen on information security outsourcing 46 Vietnam urged to strengthen land, copyright laws 12 Farmers create innovative machines to save time, costs 46 Obstacles to SOE equitisation addressed -

Vietnamese Cultural Orientation

VIETNAMESE Vietnam, one of the largest rice-growing regions of the world Flickr / ttjabeljan DLIFLC DEFENSE LANGUAGE INSTITUTE FOREIGN LANGUAGE CENTER CULTURAL ORIENTATION | Vietnamese Profile Introduction ................................................................................................................... 6 Geographic Divisions .................................................................................................. 7 Northern Highlands .............................................................................................8 Red River Valley ..................................................................................................8 Central Coast Lowlands .....................................................................................9 Central Highlands ................................................................................................9 Mekong Delta .....................................................................................................10 Climate ..........................................................................................................................12 Bodies of Water ...........................................................................................................12 Mekong River ..................................................................................................... 12 Red River ............................................................................................................ 13 Huong River ....................................................................................................... -

US Marines and Humanitarian Action During the Vietnam

Gentle Warriors: U.S. Marines and Humanitarian Action during the Vietnam War A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Lindsay Kittle June 2012 © 2012 Lindsay Kittle. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Gentle Warriors: U.S. Marines and Humanitarian Action during the Vietnam War by LINDSAY KITTLE has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Ingo W. Trauschweizer Assistant Professor of History Howard Dewald Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT KITTLE, LINDSAY, M.A., June 2012, History Gentle Warriors: U.S. Marines and Humanitarian Action during the Vietnam War Director of Thesis: Ingo W. Trauschweizer Although largely ignored in secondary literature, benevolent and humanitarian actions were an important part of the Marines’ experience during the Vietnam War. From the time the first Marines arrived in Vietnam in March of 1965, the Corp’s leadership pushed for a pacification-centered strategy aimed at securing the loyalty of the Vietnamese people. Civic action programs, therefore, were established to demonstrate the Marines good will. These programs laid the foundation for the Marines acts of humanitarianism. Many benevolent actions occurred as part of Corps’ programs, and many were initiated by individual Marines wishing to help the people of Vietnam. Their benevolence did not typify U.S. combat personnel in Vietnam, but their actions were an important part of the American experience in that war. _____________________________________________________________ Ingo W. Trauschweizer. Assistant Professor of History 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The completion of this thesis was possible with the help from many people. -

A Vietnamese Family in the United States from 1975-1985: a Case Study in Education and Culture

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1985 A Vietnamese Family in the United States from 1975-1985: A Case Study in Education and Culture Nancy Prendergast Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Prendergast, Nancy, "A Vietnamese Family in the United States from 1975-1985: A Case Study in Education and Culture" (1985). Dissertations. 2478. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2478 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1985 Nancy Prendergast A VIETNAMESE REFUGEE FAMILY IN THE UNITED STATES FROM 1975-1985: A CASE STUDY IN EDUCATION AND CULTURE by Nancy Prendergast A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 1985 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For his time, inspiration and support, I wish to extend sincere appreciation to Dr. John Wozniak, Chairman of the Doctoral Committee. Without his guidance and direction, the inception and completion of this project would never have occurred. Acknowledgement and special thanks are given to the members of the Committee, Dr. Gerald L. Gutek and Dr. Joan K. Smith for their guidance, patience, care, and support throughout this undertaking. -

Vietnam 1 Vietnam

Vietnam 1 Vietnam Socialist Republic of Vietnam Cộng hòa Xã hội chủ nghĩa Việt Nam Flag Emblem Motto: "Độc lập – Tự do – Hạnh phúc" "Independence – Freedom – Happiness" Anthem: Tiến Quân Ca [1] "Army March" Location of Vietnam(green) in ASEAN(dark grey) – [Legend] Capital Hanoi [2] 21°2′N 105°51′E Largest city Ho Chi Minh City Official languages Vietnamese Official scripts Vietnamese Ethnic groups • 85.7% Kinh (Viet) • 1.9% Tay • 1.7% Tai • 1.5% Mường • 1.4% Khơ me • 1.1% Hoa • 1.1% Nùng • 1% Hmong • 4.1% Others Demonym Vietnamese Vietnam 2 Government Marxist–Leninist single-party state - Communist Party General Secretary Nguyễn Phú Trọng - President Trương Tấn Sang - Prime Minister Nguyễn Tấn Dũng - Chairman of National Assembly Nguyễn Sinh Hùng Legislature National Assembly Formation - North Vietnam independent, national day 2 September 1945 - Fall of Saigon 30 April 1975 - Reunification 2 July 1976 - Current constitution 15 April 1992 Area - Total 331,210 km2 (65th) 128,565 sq mi [3] - Water (%) 6.4 Population - 2013 estimate 89,693,000 (13th) - Density 272/km2 (46th) 703/sq mi GDP (PPP) 2013 estimate - Total $358.889 billion (38th) - Per capita $4,001.287 (132nd) GDP (nominal) 2013 estimate - Total $170.020 billion (58th) - Per capita $1,895.576 (134th) Gini (2008) 35.6 medium HDI (2012) 0.617 medium · 127th Currency đồng (₫) (VND) Time zone Indochina Time (UTC+07:00) - Summer (DST) No DST (UTC+7) Drives on the right Calling code +84 ISO 3166 code VN Internet TLD .vn i [4] Vietnam ( /ˌviːətˈnɑːm/, /viˌɛt-/, /-ˈnæm/, /ˌvjɛt-/; Vietnamese pronunciation: [viət˨ naːm˧] ( )), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV; Cộng hòa Xã hội chủ nghĩa Việt Nam ( listen)), is the easternmost country on the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia.