The Brian Yuzna Interview Xavier Mendik

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edmond Press

International Press International Sales Venice: wild bunch The PR Contact Ltd. Venice Phil Symes - Mobile: 347 643 1171 Vincent Maraval Ronaldo Mourao - Mobile: 347 643 0966 Tel: +336 11 91 23 93 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Fax: 041 5265277 Carole Baraton 62nd Mostra Venice Film Festival: Tel: +336 20 36 77 72 Hotel Villa Pannonia Email: [email protected] Via Doge D. Michiel 48 Gaël Nouaile 30126 Venezia Lido Tel: +336 21 23 04 72 Tel: 041 5260162 Email: [email protected] Fax: 041 5265277 Silva Simonutti London: Tel: +33 6 82 13 18 84 The PR Contact Ltd. Email: [email protected] 32 Newman Street London, W1T 1PU Paris: Tel: + 44 (0) 207 323 1200 Wild Bunch Fax: + 44 (0) 207 323 1070 99, rue de la Verrerie - 75004 Paris Email: [email protected] tel: + 33 1 53 01 50 20 fax: +33 1 53 01 50 49 www.wildbunch.biz French Press: French Distribution : Pan Européenne / Wild Bunch Michel Burstein / Bossa Nova Tel: +33 1 43 26 26 26 Fax: +33 1 43 26 26 36 High resolution images are available to download from 32 bd st germain - 75005 Paris the press section at www.wildbunch.biz [email protected] www.bossa-nova.info Synopsis Cast and Crew “You are not where you belong.” Edmond: William H. Macy Thus begins a brutal descent into a contemporary urban hell Glenna: Julia Stiles in David Mamet's savage black comedy, when his encounter B-Girl: Denise Richards with a fortune-teller leads businessman Edmond (William H. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 18, 2014 Press/Media Contact: Philip Sokoloff, (626) 683-9205

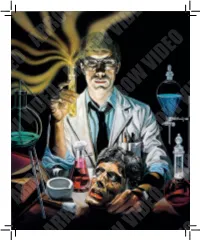

PHILIP SOKOLOFF Publicity for the theatre P.O. Box 94387 Pasadena, CA 91109-4387 (626) 683-9205 fax (626) 683-9172 e-mail: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 18, 2014 Press/media contact: Philip Sokoloff, (626) 683-9205 BACK FROM THE UNDEAD! STUART GORDON DIRECTS “RE-ANIMATOR™ THE MUSICAL” AT STEVE ALLEN THEATER; OPENS OCTOBER 17 FOR A HALLOWEEN RUN WHAT: “Re-Animator™ The Musical.” Revival of the award-winning musical hit. WHO: Book by Dennis Paoli, Stuart Gordon and William J. Norris. Music and lyrics by Mark Nutter. Adapted from the story by H.P. Lovecraft. Based on the film “H.P. Lovecraft’s Re- Animator” produced by Brian Yuzna. Musical director: Peter Adams. Choreography by Cynthia Carle. Directed by Stuart Gordon. Produced by Dean Schramm and Stuart Gordon. Presented by The Schramm Group LLC and Red Hen Productions in association with Trepany House. WHERE: The Steve Allen Theater, 4773 Hollywood Blvd., Hollywood, CA 90027. Parking lot behind building. WHEN: Previews Oct. 10, 11, 12 . Opens October 17, 2014, runs through November 2. Fridays through Sundays at 8:00 p.m. ADMISSION: $25. Previews $20. RESERVATIONS: 800-595-4849 ONLINE TICKETING: www.trepanyhouse.org * * * * * * “Re-Animator™ the Musical” has been re-animated, with new songs and new performers just in time for Halloween. “RE-ANIMATOR™ the Musical” tells the story of Herbert West, a brilliant young medical student who has created a glowing green serum that can bring the dead back to life. What should be a medical breakthrough results in hideous monstrosities and ghastly consequences. “I guess he just wasn’t fresh enough,” is West’s constant refrain in his quest for fresh subjects. -

Beneath Still Waters: Brian Yuzna's Ritual Return in Indonesian Cinema

Beneath Still Waters: Brian Yuzna’s Ritual Return in Indonesian Cinema Xavier Mendik This article offers the first academic consideration of Brian Yuzna’s recent films created in Indonesia. Since the mid 1980s, Yuzna has worked extensively across the USA, Europe and the Far East (both as a director and producer), pioneering a distinctive international brand of horror cinema that combines social critique with explicit splatter. Despite his transnational credentials, Yuzna’s work in Indonesia has largely been ignored by those critics interested in reclaiming 1970s/80s genre entries as more ‘legitimate’ symbols of Indonesian cult cinema. However, by considering Yuzna’s 2010 title Amphibious, I shall argue that the film contains the elements of hybridity and generic impurity that critics such as Karl G. Heider have long attributed to Indonesian pulp traditions. Specifically, it shall be argued that the film’s emphasis on performativity, trickery and spectacle are used to evoke Indonesian myths rather than Americanised tropes of genre cinema. As well as considering the transnational elements to Amphibious, the article will also explore possible connections between abject constructions of the transformative female body in both Indonesian film and Brian Yuzna’s wider cinema. The article also features exclusive new interviews with Brian Yuzna and Amphibious screenwriter John Penney discussing the making and meaning of the film. Keywords: Brian Yuzna, Indonesian horror, Amphibious, transnational cinema . a cinema can be defined as transnational in the sense that it brings into question how fixed ideas of a national film culture are constantly being transformed by the presence of protagonists (and indeed film-makers) who have a presence within the nation, even if they exist on the margins, but find their origins quite clearly beyond it. -

Taylor Doctoralthesis Complete

21st Century Zombies: New Media, Cinema, and Performance By Joanne Marie Taylor A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Peter Glazer, Chair Professor Brandi Wilkins Catanese Professor Kristen Whissel Fall 2011 21st Century Zombies: New Media, Cinema, and Performance © 2011 by Joanne Marie Taylor Abstract 21st Century Zombies: New Media, Cinema, and Performance by Joanne Marie Taylor Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies and a Designated Emphasis in Film Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Peter Glazer, Chair This project began with a desire to define and articulate what I have termed cinematic performance, which itself emerged from an examination of how liveness, as a privileged performance studies concept, functions in the 21st century. Given the relative youth of the discipline, performance studies has remained steadfast in delimiting its objects as those that are live—shared air performance—and not bound by textuality; only recently has the discipline considered the mediated, but still solely within the circumscription of shared air performance. The cinema, as cultural object, permeates our lives—it is pervasive and ubiquitous—it sets the bar for quality acting, and shapes our expectations and ideologies. The cinema, and the cinematic text, is a complex performance whose individual components combine to produce a sum greater than the total of its parts. The cinema itself is a performance—not just the acting—participating in a cultural dialogue, continually reshaping and challenging notions of liveness, made more urgent with the ever-increasing use of digital technologies that seem to further segregate what is generally considered real performance from the final, constructed cinematic text. -

Zombies: New Media, Cinema, and Performance

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title 21st Century Zombies: New Media, Cinema, and Performance Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9hq1z1t7 Author Taylor, Joanne Marie Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 21st Century Zombies: New Media, Cinema, and Performance By Joanne Marie Taylor A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Peter Glazer, Chair Professor Brandi Wilkins Catanese Professor Kristen Whissel Fall 2011 21st Century Zombies: New Media, Cinema, and Performance © 2011 by Joanne Marie Taylor Abstract 21st Century Zombies: New Media, Cinema, and Performance by Joanne Marie Taylor Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies and a Designated Emphasis in Film Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Peter Glazer, Chair This project began with a desire to define and articulate what I have termed cinematic performance, which itself emerged from an examination of how liveness, as a privileged performance studies concept, functions in the 21st century. Given the relative youth of the discipline, performance studies has remained steadfast in delimiting its objects as those that are live—shared air performance—and not bound by textuality; only recently has the discipline considered the mediated, but still solely within the circumscription of shared air performance. The cinema, as cultural object, permeates our lives—it is pervasive and ubiquitous—it sets the bar for quality acting, and shapes our expectations and ideologies. -

Spanish Horror Co-Productions in the Post-2000 Revival: New Partners and Challenges

Spanish horror co-productions in the post-2000 revival: new partners and challenges Rui Oliveira ([email protected]) Mass Communication – Faculty of Arts, Design and Social Sciences Northumbria University 1 Spanish horror co-productions • What production companies are responsible for the new output of horror co- productions in the Spanish film industry? • Who are now their main international partners? • How has the crisis affected these companies? 2 Spanish horror co-productions First Period (mid-1960s to early 1980s): • Italy and Spain were two of the largest producers of horror films in Europe. • Italy was Spain’s main business partner in genre cinema (including horror). • Other relevant partners: France, West Germany and UK. • Mostly under bilateral or multilateral co-production treaties. • Ley Miró (Miró Law) in 1983 leads to a dramatic reduction in Spanish horror co-productions. 3 Spanish horror co-productions Late 1980s: • European Union’s MEDIA programme: created in 1987. • Eurimages programme by the Council of Europe, in 1989: encourages the co-production, distribution and exploitation of European cinema. Mid-1990s: • Restructuring in the film regulations and subsidy policies in Spain. • Fundamental changes in the financing of the Spanish film industry. 4 The late 1990s, early 2000s: Sogetel and Sogecine 1990 - 1996 1997 Production Distribution 5 The late 1990s, early 2000s: Sogetel and Sogecine El Dia de La Bestia (Spain/Italy, Abre los Ojos (Spain/Italy/France, Álex de La Iglesia, 1995) Alejandro Aménabar, 1997) 6 The late 1990s, early 2000s: Sogetel and Sogecine Los Otros/The Others (Alejandro Aménabar, 2001) ▪ Spain: Sogecine + Las Producciones del Escorpeón (José Luis Cuerda) ; Warner Sogefilms (distribution) ▪ U.S.: Cruise/Wagner Productions (production) ; Dimension Films (U.S. -

CV Richard Raaphorst Director

CV Richard Raaphorst Director Graduated AV MEDIA at the school of fine arts Willem de Kooning Rotterdam. Became a freelancer in storyboarding, a commercial director, 2nd unit director and a title designer. Represented by agency ‘Roughmen’ from 1997 until present. Over the years, I’ve worked for many directors as a storyboard artist / concept artist. Such as: Terry Gilliam (NIKE Campaign-agency Wieden and Kennedy) David Fincher (MOTOROLA-campaign Agency 180 Amsterdam). Who Am I – 1999 Jacky Chen Faust - 2000, Directed by Brian Yuzna Beyond - 2003 Re-Animator, Rottweiler - 2004, Beneath Still Waters - (2005) and Amphibious - 2010 Dagon - 2001 directed by Stuart Gordon Fragile - 2005 directed Jaume Balagueró Blackboek - 2006 directed by Paul Verhoeven Witlicht - 2008 directed by Jean van de velde Undone Tv series - 2019 Directed by Hisko Hulsing Forgotten Battle Slag om de Schelde – 2020 Directed by Matthijs van Heijningen jr. Pressent, I have a 2nd feature film in preproduction, Produced by Holland harbor. Besides directing commercials, I’ve also directed stop motion animation and worked extensively with computer graphics. In 2013 I finished my feature, ‘Frankenstein’s Army (Dark Sky pictures), which became a cult hit worldwide and a big hit in Japan. Currently I have 1 project in development: HIGGS, a scifi thriller represented by Ratpak Germany and Holland harbour I also co produce 2017, founder of the Mad Science Movement, A special effects company. In production: Rock of ages (last stages of post production) short directed by Eron Sheean -

Thoughts for the Month Column

Jeff Kirkendall’s Thoughts For The Month Column Thoughts, Opinions, Reviews, Commentary & More! Hello and Welcome! My name is Jeff Kirkendall and I'm an independent filmmaker and actor from the Upstate New York area. This is the section of the Very Scary Productions website where I write about topics related to independent filmmaking, digital video production, acting, movies in general, horror movies in particular, my own indie movies, as well as anything and everything related or in between. I decided to create this commentary page because I find that I often come across things that either interest me, excite me, intrigue me, or maybe just bug me. Any topic related to movies and cinema is fair game, from the most mainstream to the most controversial. For example I'll often read about movie projects that I have a strong interest in or opinion on, for one reason or another. This page gives me a forum to discuss these things. It's all about discussion and furthering understanding of our pop culture. Anyone who has feedback concerning what I have to say here, feel free to contact me (see the contact link at http://www.veryscaryproductions.com/). I'd also like to point out that the following is just my opinion, and everyone is free to agree or disagree with what I have to say. Enjoy, and to all the Indies out there: Keep on Filming! SUBJECT: Movie Review: Beyond Re-Animator - Dr. Herbert West returns to the screen! – March 2004 For those not familiar with the Re-Animator film series, the movies follow the horrific adventures of one Doctor Herbert West, played by genre favorite Jeffrey Combs. -

BAJO AGUAS TRANQUILAS BENEATH STILL WATERS (España/Spain 78%-Reino Unido/U.K

BAJO AGUAS TRANQUILAS BENEATH STILL WATERS (España/Spain 78%-Reino Unido/U.K. 22%) Dirigido por/Directed by BRIAN YUZNA Productoras/Production Companies: CASTELAO PRODUCTIONS, S.A. (78%) Miguel Hernández, 81-87. Polígono Pedrosa. 08908 L'Hospitalet de Llobregat (Barcelona). Tel. 93 336 85 55. Fax 93 336 85 68. www.filmax.com E-mail: [email protected] FUTURE FILMS LIMITED. (22%) 76 Dean Street. W1D 3SQ London. (Reino Unido) Tel. +44 (0)20 7009 6600. Fax +44 (0)20 7009 6602. www.futurefilmgroup.com E-mail: [email protected] Con la participación de/with the participation of: CANAL+ ESPAÑA. Director: BRIAN YUZNA. Producción/Producer: JULIO FERNÁNDEZ. Coproducción/Co-producer: KWESI DICKSON. Producción asociada/Associate Producer: CAROLA ASH. Dirección de producción/Line Producers: TERESA GEFAELL, JOSÉ LUIS JIMÉNEZ. Jefe de producción/Production Manager: TERESA CEPEDA. Productor creativo/Creative Producer: BRIAN YUZNA. Coproducción ejecutiva/Co-Executive Producers: JULIO FERNÁNDEZ, CARLOS FERNÁNDEZ. Guión/Screenplay: ÁNGEL SALA, MIKEL HOSTENCH. Argumento/Plot: Basado en la novela/Based on the novel “Beneath Still Waters” de MATTHEW COSTELLO. Fotografía/Photography: JOHNNY YEBRA. Música/Score: ZACARÍAS M. DE LA RIVA. Dirección artística/Production Design: BALTER GALLART. Vestuario/Costume Design: BETTY CALVO. Montaje/Editor: NICOLAS CHAUDEURGE. Sonido/Sound: ÁLVARO LÓPEZ, DANIEL PEÑA. Ayudante de dirección/Assistant Director: TXARLI LLORENTE. Web: http://bajoaguastranquilas.filmax.com Casting: PEP ARMENGOL ; LUCI LENNOX, JULIE DUNNE (Casting U.K.). Maquillaje/Make-up: ALMUDENA FONSECA. Peluquería/Hairdressing: MARTHA MARÍN. Efectos especiales/Special Effects: PEDRO DE DIEGO, RAÚL ROMANILLOS, ÓSCAR APARICIO, J. RAMÓN MOLINA. Efectos digitales/Visual Effects: MARIANO LIWSKI (Supervisión). Intérpretes/Cast: MICHAEL MCKELL (Dan), RAQUEL MEROÑO (Teresa), CHARLOTTE SALT (Clara), PATRICK GORDON (Salas), PILAR SOTO (Susana), JOSEP MARIA POU (Gambine), MANUEL MANQUIÑA (Luis), DIANA PEÑALVER (Mrs. -

ROTTWEILER (España/Spain 80%-Reino Unido/U.K

ROTTWEILER (España/Spain 80%-Reino Unido/U.K. 20%) Dirigido por/Directed by BRIAN YUZNA Productoras/Production Companies: CASTELAO PRODUCTIONS, S.A. (79,7%) Miguel Hernández, 81-87. Polígono Pedrosa. 08908 L'Hospitalet de Llobregat (Barcelona). Tel. 93 336 85 55. Fax 93 336 85 68. www.filmax.com E-mail: [email protected] FUTURE FILMS LIMITED. (20,3%) 76 Dean Street. W1D 3SQ London. (Reino Unido) Tel. +44 (0)20 7009 6600. Fax +44 (0)20 7009 6602. www.futurefilmgroup.com E-mail: [email protected] Con la participación de/with the participation of: CANAL+ ESPAÑA. Director: BRIAN YUZNA. Producción/Producer: JULIO FERNÁNDEZ. Producción ejecutiva/Executive Producers: JULIO FERNÁNDEZ, CARLOS FERNÁNDEZ. Coproducción/Co-producers: ALBERT MARTÍNEZ MARTÍN, COPRODUCTOR EJECUTIVO: STEPHEN MARGOLIS. Producción asociada/Associate Producer: CAROLA ASH. Dirección de producción/Line Producers: TERESA GEFAELL, REYES MATABUENA. Productor creativo/Creative Producer: BRIAN YUZNA. Guión/Screenplay: ALBERTO VÁZQUEZ-FIGUEROA, DIÁLOGOS ADICIONALES: MIGUEL TEJADA FLORES. Argumento/Plot: Basado en la novela "El perro" de/Based on the novel “The Dog” by ALBERTO VÁZQUEZ-FIGUEROA. Fotografía/Photography: JAVIER SALMONES A.E.C. Música/Score: MARK THOMAS. Diseño de producción/Production Design: BALTER GALLART. Montaje/Editor: ANDY HORVITCH. Sonido/Sound: ALBERT MANERA. Mezclas/Re-recording Mixer: RICHARD LEWIS. Ayudantes de dirección/Assistants Director: IGNACIO GUTIÉRREZ-SOLANA, FERNANDO TRULLOLS SANTIAGO. Casting: PEP ARMENGOL, CAROL DUDLEY CGD - CSA. Web: http://rottweiler.filmax.com Maquillaje/Make-up: PEPE QUETGLAS. Peluquería/Hairdressing: MARA COLLAZO. Efectos especiales/Special Effects: VINCENT GUASTINI PRODUCTIONS, PEPE QUETGLAS, ADOLFO VILA. Efectos digitales/Visual Effects: INFINIA. Diseño y Creación de Rottweiler/Rottweiler Created & Designed by: V.G.P. -

George Eastman House Annual Report 2013

George Eastman House Annual Report 2013 Contents Exhibitions 2 Traveling Exhibitions 3 Film Series at the Dryden Theatre 4 Program Highlights 5 Online Access 6 Education 7 Loans 9 Acquisitions 13 Conservation & Preservation 18 Financial 20 Fundraising 22 Trustees, Advisors & Staff 31 900 East Avenue, Rochester, NY 14607 | eastmanhouse.org Exhibitions Ballyhoo: The History of Space Photography Ongoing The Art of Selling the Movies Curated by Jay Belloli for the Curated by Caroline Yeager, California/International Arts Kodak Camera at 125 assistant curator of motion pictures Foundation, Los Angeles, California Curated by Todd Gustavson, March 10, 2012–January 27, 2013 October 26, 2013–January 12, 2014 technology curator Opened September 2013 60 from the 60s Astro-Visions Curated by Alison Nordström, Curated by Jamie Allen, assistant Machines of Memory: Cameras senior curator of photographs; and curator of photographs from the Technology Collection Jamie Allen, assistant curator of October 26, 2013–January 12, 2014 Curated by Todd Gustavson, photographs technology curator October 6, 2012–January 27, 2013 Bigger Than Life: CinemaScope at 60 Photo/Film History Timeline Camera Obscura Curated by James Layton, assistant Curated by Jessica Johnston, Curated by Jessica Johnston, archivist; Shota Ogawa, University assistant curator of photographs assistant curator of photographs; and of Rochester fellow; Edward S. The Remarkable George Eastman Todd Gustavson, technology curator Stratmann, associate curator; and Curated by Kathy Connor, curator of December 22, 2012–May 12, 2013 Anthony L’Abbate, preservation George Eastman Legacy Collection; officer, of the Motion Picture and Rick Hock, director of exhibitions Dutch Connection Department Curated by Amy Kinsey, Nancy R. -

Arrow Video Arrow Vi Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Vi

ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO 1 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO CAST JEFFREY COMBS as Herbert West ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO BRUCE ABBOTT as Dan Cain BARBARA CRAMPTON as Megan Halsey DAVID GALE as Dr. Carl Hill ROBERT SAMPSON as Dean Halsey ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO CREW Directed by STUART GORDON Produced by BRIAN YUZNA Screenplay by STUART GORDON, WILLIAM J. NORRIS and DENNIS PAOLI (Based on H.P. Lovecraft’s “Herbert West – Reanimator”) Cinematography by MAC AHLBERG Edited by LEE PERCY ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO Music composed by RICHARD BAND ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO 2 3 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO CONTENTS 3 Film Credits ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO 7 Yucking It Up: The Black (and Red) Humor of Re-Animator by Michael Gingold ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO 20 About the Transfer 4 5 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO YUCKING IT UP: THE BLACK (AND RED) HUMOR OF “RE-ANIMATOR” by Michael Gingold Terror and comedy are often said to be two sides of the same cinematic coin; both are all about buildup and release. Combining the two, however, has always been a tricky business; many have tried, yet the road to horror/humor hell is littered with the corpses of films that couldn’t get the balance right, or elicit either emotion effectively.