ABSTRACT a HISTORICAL-CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS of the FINAL-GENERATION THEOLOGY of M. L. ANDREASEN by Paul M. Evans Adviser: Jerry A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses

Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. The present study has been based as far as possible on primary sources such as protocols, letters, legal documents, and articles in journals, magazines, and newspapers from the nineteenth century. A contextual-comparative approach was employed to evaluate the objectivity of a given source. Secondary sources have also been consulted for interpretation and as corroborating evidence, especially when no primary sources were available. The study concludes that the Pietist revival ignited by the Norwegian Lutheran lay preacher, Hans Nielsen Hauge (1771-1824), represented the culmination of the sixteenth- century Reformation in Norway, and the forerunner of the Adventist movement in that country. -

The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-Day Adventist Church from the 1840S to 1889" (2010)

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2010 The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh- day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889 Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Snorrason, Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik, "The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889" (2010). Dissertations. 144. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/144 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. -

The God of Our Fathers

0 The God of Our Fathers This manuscript is designed to be a catalyst for further personal study By Kelvin D Cobbin 1 The God of Our Fathers An intriguing look into the emergence of the trinity doctrine within the Seventh-Day Adventist Church Great changes to an organisation are usually long and protracted and in many cases are often undetected, except to those responsible for instigating the change. Throughout this paper I have endeavoured to give an accurate account of the most significant theological shift to have ever taken place in the Seventh-Day Adventist Church. There has been a considerable amount of material written in regards to this change from those endeavouring to justify the change, and on the other hand, those who are disturbed with the change and feel that not only was it unjustified but it has plunged the church and its future into jeopardy. It is my intention to put together a compelling account, from historical records, from biblical evaluation, and from the prophet to the remnant to show that this change was indeed the most extraordinary shift of fundamental belief within the history of our Denomination. There’s a promise from God to Israel in Isa 42:16 which I believe is for just such a time “...I will make darkness light before them and crooked things straight...” BBBibleBible quotes from the King James Version 2 TTTheThheehe GGooGodGoddd ooffof OOuurrOur FFaatthheerrssFathers FFoorrwwaarrddForward It was in 1996 that I was first challenged to take another look at the doctrine of the trinity which, I thought, could be clearly supported from the Bible. -

Page 1 Historic Name: ELMSHAVEN Other Name/Site Number: Ellen

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ELMSHAVEN Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: ELMSHAVEN Other Name/Site Number: Ellen White House; Robert Pratt Place 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 125 Glass Mountain Lane Not for publication: City/Town: St. Helena Vicinity: State: CA County: Napa Code: 055 Zip Code: 94574 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private; X Building(s) :__ Public-Loca1:__ District: X Public-State:__ Site:__ Public-Federal: Structure:__ Object:__ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 3 1 buildings ____ sites ____ structures ____ objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 0 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ELMSHAVEN Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

The Pneuma Network: Transnational Pentecostal Print Culture in The

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 4-18-2016 The neumP a Network: Transnational Pentecostal Print Culture In The nitU ed States And South Africa, 1906-1948 Lindsey Brooke Maxwell Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC000711 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, History of Christianity Commons, History of Religion Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, New Religious Movements Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Maxwell, Lindsey Brooke, "The neP uma Network: Transnational Pentecostal Print Culture In The nitU ed States And South Africa, 1906-1948" (2016). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2614. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/2614 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida THE PNEUMA NETWORK: TRANSNATIONAL PENTECOSTAL PRINT CULTURE IN THE UNITED STATES AND SOUTH AFRICA, 1906-1948 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by Lindsey Brooke Maxwell 2016 To: Dean John F. Stack, Jr. choose the name of dean of your college/school College of Arts, Sciences and Education choose the name of your college/school This dissertation, written by Lindsey Brooke Maxwell, and entitled The Pneuma Network: Transnational Pentecostal Print Culture in the United States and South Africa, 1906-1948, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. -

The Historical Development of the Religion Curriculum at Battle Creek College, 1874-1901

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2001 The Historical Development of the Religion Curriculum at Battle Creek College, 1874-1901 Medardo Esau Marroquin Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Education Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Marroquin, Medardo Esau, "The Historical Development of the Religion Curriculum at Battle Creek College, 1874-1901" (2001). Dissertations. 558. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/558 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Lest We Forget | 4

© 2021 ADVENTIST PIONEER LIBRARY P.O. Box 51264 Eugene, OR, 97405, USA www.APLib.org Published in the USA February, 2021 ISBN: 978-1-61455-103-4 Lest We ForgetW Inspiring Pioneer Stories Adventist Pioneer Library 4 | Lest We Forget Endorsements and Recommendations Kenneth Wood, (former) President, Ellen G. White Estate —Because “remembering” is es- sential to the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the words and works of the Adventist pioneers need to be given prominence. We are pleased with the skillful, professional efforts put forth to accom- plish this by the Pioneer Library officers and staff. Through books, periodicals and CD-ROM, the messages of the pioneers are being heard, and their influence felt. We trust that the work of the Adventist Pioneer Library will increase and strengthen as earth’s final crisis approaches. C. Mervyn Maxwell, (former) Professor of Church History, SDA Theological Semi- nary —I certainly appreciate the remarkable contribution you are making to Adventist stud- ies, and I hope you are reaching a wide market.... Please do keep up the good work, and may God prosper you. James R. Nix, (former) Vice Director, Ellen G. White Estate —The service that you and the others associated with the Adventist Pioneer Library project are providing our church is incalculable To think about so many of the early publications of our pioneers being available on one small disc would have been unthinkable just a few years ago. I spent years collecting shelves full of books in the Heritage Room at Loma Linda University just to equal what is on this one CD-ROM. -

An Evaluation of the Modern Church in Light of the Early Church: the Case of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church in the Democratic Republic of Congo

AN EVALUATION OF THE MODERN CHURCH IN LIGHT OF THE EARLY CHURCH: THE CASE OF THE SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO by KAKULE MITHIMBO PAUL Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY in the subject CHURCH HISTORY at the UNIVRSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF P H GUNDANI NOVEMBER 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................... III LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................... VIII LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................... XI ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................. XII SUMMARY ............................................ ERREUR ! SIGNET NON DEFINI. III DEDICATION ............................................................................................ XV INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 1 TOPIC……. ................................................................................................................. 1 1. AREA OF INVESTIGATION ................................................................................... 1 1.1. Problem Statement .................................................................................................................. 1 1.2. Area of Investigation ............................................................................................................... -

Some Highlights of the Life of James Springer White (1821-1881) ( See "James White, a Man of Action" Lest We Forget, Vol

Some Highlights of the Life of James Springer White (1821-1881) (www.APLib.org) See "James White, a Man of Action" Lest We Forget, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 4-6 (Lest We Forget, Vol. 5, Nos. 1, 2, 3 cover James White) Recommended: Life Incidents: Connection With the Great Advent Movement, As Illustrated by the Three Angels of Revelation XIV, 1868. Ancestry, Early Life, Christian Experience, and Extensive Labors, of Elder James White, and His Wife, Mrs. Ellen G. White, 1880. (Chapter 5-9 deal mostly with Ellen White.) Date Age Event 1821/08/04 0 Born in Palmyra, Maine, middle of nine children 1836 15 Baptized into the Christian Church fellowship 1840 19 Entered into the academy at St. Albans, Maine; soon taught his first school At the age of twenty I had buried myself in the spirit of study and school teaching, and had lain down the cross.... I loved this world more than I loved Christ and the next, and was worshiping education instead of the God of Heaven. [His mother's appeal and the witness of friends convicted him of Advent message. He came under conviction similar to William Miller, to share with the students he had taught. After initially rejecting the conviction, he did so. Then he struggled over what his future should be, wanting still to be a teacher.] I finally gave all for Christ and his gospel, and found peace and freedom. {1868 JW, LIFIN 15.2 & 24.5} 1841 20 Joined the Millerites; shared the message of the advent in Troy, Maine 1842/09 21 First heard Miller preach at a meeting in the mammoth tent in Eastern Maine On returning from the great camp-meeting in Eastern Maine, where I heard with deepest interest such men as Miller, Himes, and Preble, I found myself happy in the faith that Christ would come about the year 1843. -

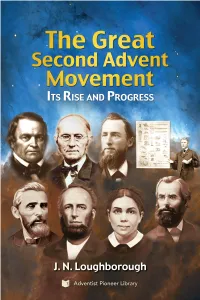

The Great Second Advent Movement.Pdf

© 2016 Adventist Pioneer Library 37457 Jasper Lowell Rd Jasper, OR, 97438, USA +1 (877) 585-1111 www.APLib.org Originally published by the Southern Publishing Association in 1905 Copyright transferred to Review and Herald Publishing Association Washington, D. C., Jan. 28, 1909 Copyright 1992, Adventist Pioneer Library Footnote references are assumed to be for those publications used in the 1905 edition of The Great Second Advent Movement. A few references have been updated to correspond with reprinted versions of certain books. They are as follows:— Early Writings, reprinted in 1945. Life Sketches, reprinted in 1943. Spiritual Gifts, reprinted in 1945. Testimonies for the Church, reprinted in 1948. The Desire of Ages, reprinted in 1940. The Great Controversy, reprinted in 1950. Supplement to Experience and Views, 1854. When this 1905 edition was republished in 1992 an additional Preface was added, as well as three appendices. It should be noted that Appendix A is a Loughborough document that was never published in his lifetime, but which defended the accuracy of the history contained herein. As noted below, the footnote references have been updated to more recent reprints of those referenced books. Otherwise, Loughborough’s original content is intact. Paging of the 1905 and 1992 editions are inserted in brackets. August, 2016 ISBN: 978-1-61455-032-7 4 | The Great Second Advent Movement J. N. LOUGHBOROUGH (1832-1924) Contents Preface 7 Preface to the 1992 Edition 9 Illustrations 17 Chapter 1 — Introductory 19 Chapter 2 — The Plan of Salvation -

Ellen White: Woman of Vision

Ellen White: Woman of Vision Arthur L. White 2000 Copyright © 2017 Ellen G. White Estate, Inc. Information about this Book Overview This eBook is provided by the Ellen G. White Estate. It is included in the larger free Online Books collection on the Ellen G. White Estate Web site. About the Author Ellen G. White (1827-1915) is considered the most widely translated American author, her works having been published in more than 160 languages. She wrote more than 100,000 pages on a wide variety of spiritual and practical topics. Guided by the Holy Spirit, she exalted Jesus and pointed to the Scriptures as the basis of one’s faith. Further Links A Brief Biography of Ellen G. White About the Ellen G. White Estate End User License Agreement The viewing, printing or downloading of this book grants you only a limited, nonexclusive and nontransferable license for use solely by you for your own personal use. This license does not permit republication, distribution, assignment, sublicense, sale, preparation of derivative works, or other use. Any unauthorized use of this book terminates the license granted hereby. Further Information For more information about the author, publishers, or how you can support this service, please contact the Ellen G. White Estate at [email protected]. We are thankful for your interest and feedback and wish you God’s blessing as you read. i Contents Information about this Book . .i Introduction . xv Ellen G. White and Her Writings . xv Foreword ........................................... xvii About The Author . xx Chapter 1—The Time Was Right. 22 Ellen’s Developing Christian Experience . -

The Influence of Changes on Historical Standards in Selected Urban Seventh-Day Adventist Churches in Kenya by Rei Towet Kesis C8

THE INFLUENCE OF CHANGES ON HISTORICAL STANDARDS IN SELECTED URBAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCHES IN KENYA BY REI TOWET KESIS C82/13400/2009 THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES, IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY SEPTEMBER 2014 ii DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university. Signature_____________________________________ Date___________ Rei Towet Kesis Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies We confirm that the work presented in this Thesis was carried out by the candidate under our supervision and has been submitted with our approval as university supervisors. Signature_____________________________________ Date___________ Dr. Zacharia W. Samita Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies Kenyatta University Signature_____________________________________ Date___________ Dr. Humphrey M. Waweru Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies Kenyatta University iii DEDICATION To the one and only true God for whom this work and its consequences bring glory now and forever! iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The process of researching, writing, correcting and eventually producing this thesis has involved help from many people who I may not be able to exhaustively list here. However, I wish to express my gratitude to the LORD God almighty for His intervention in this process. He alone deserves credit. My regards go to Mrs. Clara Chemtai Towet, my wife and my son Gamaliel Kibet Towet who bore with the demands of this process and were a motivation. Pastor Peter Kesis, my father, kept calling daily to inquire on the progress of this work and praying for this work even on phone.