<I>Healthy Lifestyles Cooking Like a Chef (HLCLC)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deeds, Wills, Administrations of Jefferson County, State of Alabama

1 DEEDS – WILLS – ADMINISTRATIONS OF JEFFERSON COUNTY, ALABAMA BOOK 2 Vol. V 1833 – 1837 Page 221 – 289 Vol. VI 1836 – 1839 Page 290 – 378 Vol. VII 1839 – 1840 Page 379 – 467 Vol. VII 1840 – 1844 Page 468 – 1844 Birmingham Public Library Birmingham, Alabama Works Progress Administration 1937 2 STATE OF ALABAMA – JEFFERSON COUNTY DEEDS – WILLS – ADMINISTRATIONS 1833 – 1837 Vol. 5 MORTGAGE DEED Page 1 & 2 REASON DUKE to PEYTON KING, trustee, both of Jeff. Co. Ala. Premisis. All corn now on hand and a black horse, cupboard, two tables, 4 chairs, 2 beds and their furniture, and two bed steads, his crop of corn and cotton now planted. Whereas, Jason Addington is security for Reason Duke, in three notes, Viz: One to Curtis Williams in the sum $120, one to Lightfoot Williams, in the sum of $13, and the other to John Martin, in the sum of $64. Reason Duke being willing to secure the payment of said debts, executes this deed of trust Dated Apr. 3, 1833. Ack. Before B. E. Grace Clk. of C.C. Apr. 3, 1833. Filed Apr. 3. Recorded Apr. 15, 1833. B. E. Grace, Clk. of C.C. MORTGAGE Page 2 & 3 DANIEL WATKINS TO BAYLIS E. GRACE, both of Jeff. Co. Ala. Premises. One sorrel mare with a blazed face, about eleven or twelve yrs. Old. Whereas, Watkins is indebted to Grace in the sum of $20.93 ¾, due by note payable to Grace & Kelly. And Watkins being willing to secure the payment of same, executes this mortgage. Wit. Abner Killough Dated Apr. -

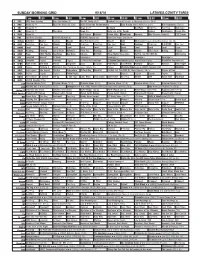

Sunday Morning Grid 9/18/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/18/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2016 Evian Golf Championship Auto Racing Global RallyCross Series. Rio Paralympics (Taped) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch BestPan! Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Skin Care 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Vista L.A. at the Parade Explore Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Why Pressure Cooker? CIZE Dance 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Good Day Game Day (N) Å 13 MyNet Arthritis? Matter Secrets Beauty Best Pan Ever! (TVG) Bissell AAA MLS Soccer Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Church Faith Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Paid Prog. AAA Cooking! Paid Prog. R.COPPER Paid Prog. 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Three Nights Three Days Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. ADD-Loving 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Pagado Secretos Pagado La Rosa de Guadalupe El Coyote Emplumado (1983) María Elena Velasco. -

A Collaborative Inquiry: Working Together to Make Our Reading Recovery Lessons Culturally Responsive

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Middle and Secondary Education Dissertations Department of Middle and Secondary Education 1-8-2016 A collaborative inquiry: Working together to make our Reading Recovery lessons culturally responsive Danielle M. HIlaski Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/mse_diss Recommended Citation HIlaski, Danielle M., "A collaborative inquiry: Working together to make our Reading Recovery lessons culturally responsive." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2016. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/mse_diss/18 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Middle and Secondary Education at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Middle and Secondary Education Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACCEPTANCE This dissertation, A COLLABORATIVE INQUIRY: WORKING TOGETHER TO MAKE OUR READING RECOVERY LESSONS CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE, by DANIELLE HILASKI, was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s Dissertation Advisory Committee. It is accepted by the committee members in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Philosophy, in the College of Education and Human Development, Georgia State University. The Dissertation Advisory Committee and the student’s Department Chairperson, as representatives of the faculty, certify that this dissertation has met all standards of excellence and scholarship as determined by the faculty. The Dean of the College of Education concurs. Amy Seely Flint, Ph.D. Committee Chair Caitlin Dooley, Ph.D. Laura May, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member Lisa Lang, Ph.D. Committee Member Date Gertrude Tinker Sachs, Ph.D. -

Nurse Ran Scam on Patient, Say Cops

A3 + PLUS >> Get real, Sen. Book, Opinion/4A CHS SOCCER ANNUAL PAGEANT Boys, girls reach The ladies district quarters of Olustee See Page 5A See Page 2A TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 4, 2020 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $1.00 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM Whose nutty Rogue lawmaker wants to make coconut idea is this? patties the official state candy. We object. 3A CLEANUP FRAUD ALLEGED Taking pride Nurse ran in their scam on city patient, Volunteers gather to spruce Lake City up before visitors arrive. say cops By MICHAEL PHILIPS [email protected] Caretaker was stealing from City Manager Joe accounts, LCPD report says. Helfenberger stood in front a map of Lake City, a gen- eral marshaling a company By CARL MCKINNEY of volunteers in the battle [email protected] against trash. As the orga- A nurse tried to steal from her patient, nizer of the inaugural “Take who happened to have a background in Pride in Your Community both finance and crim- Clean-Up Campaign,” he inal justice, according had to make sure volun- to the Lake City Police teers made it to areas that Department. needed trash and litter Lorene Jane Owens, removed. 50, of Southeast Waldron “We are trying to cover Terrace, was arrested on the entire city, all four multiple charges Friday quadrants,” Helfenberger Owens afternoon. told the Reporter. “This is When police responded the first time we’re holding to a fraud reported at Southwest Zesty the event, Circle around 4:27 p.m., Owens flagged and we ‘We’ve down an officer’s patrol vehicle before weren’t trying to paint the victim as an unreliable seen a lot sure how of cooper- witness. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Cablefax Dailytm Friday — June 7, 2013 What the Industry Reads First Volume 24 / No

URGENT! PLEASE DELIVER www.cablefaxdaily.com, Published by Access Intelligence, LLC, Tel: 301-354-2101 6 Pages Today CableFAX DailyTM Friday — June 7, 2013 What the Industry Reads First Volume 24 / No. 110 FX Exchange: Landgraf Talks Sr Management, Distribution, Password Sharing Just because John Landgraf was promoted to CEO of FX Networks, don’t get any ideas that he’ll start running a fiefdom over there. Repeatedly during a press conference Thurs, Landgraf said he wanted to FX Nets to “remain boutique,” with execs throwing around adjectives like “scrappy” and “indie.” And he’s not going to roll out the standard programming structure and put individual execs in charge of FX, FXX and FXM, instead naming Nick Grad and Eric Schrier both as presidents of original programming for FX Nets and FX Productions, overseeing all original programming for the 3 nets. Chuck Saftler was upped to pres, program strategy and COO, FX Nets, with him over- seeing programming strategies for all the nets. “I just don’t believe in those kind of structures,” he said, referring to separate pres/gm posts for each channel. “I don’t want Nick’s intellect, creativity and administrative ability to be focused on one channel, and Eric to be focused on another.” Grad previously served as evp, original programming and dev for FX. Schrier formerly was evp, FX Productions and head of series development for FX, while Saftler was evp, FX Nets and gm, FXM. FXX, launching in Sept, is the net’s 1st original series, an animated show from the creative teams behind “Eastbound & Down” and “Archer.” It will join “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia” and “The League,” which are moving from FX. -

HBO's Interventions in Popular Culture Shayne Pepper Northeastern Illinois University, [email protected]

Northeastern Illinois University NEIU Digital Commons Communication, Media and Theatre Faculty Communication, Media and Theatre Publications 2012 Public Service Entertainment: HBO's Interventions in Popular Culture Shayne Pepper Northeastern Illinois University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://neiudc.neiu.edu/cmt-pub Recommended Citation Pepper, Shayne, "Public Service Entertainment: HBO's Interventions in Popular Culture" (2012). Communication, Media and Theatre Faculty Publications. 2. https://neiudc.neiu.edu/cmt-pub/2 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication, Media and Theatre at NEIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication, Media and Theatre Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of NEIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected],[email protected]. CHAP TER 6 } Public Service Entertainment HBO’s Interventions in Politics and Culture Shayne Pepper When one thinks of “public service,” HBO is not typically the media entity that comes to mind. However, in examining HBO’s forty-year history, one notices an extensive list of socially conscious, politically engaged, and even outright public service programs. Over the years, HBO has brought a great deal of thoughtful (and sometimes controversial) cultural programming into American households. This group of films explores topics such as poverty, AIDS, women’s rights, and global injustice, often fiercely critiquing systems of inequality and oppression. Sometimes these programs even provide potential solutions and avenues of hope for some of today’s most important social problems. For example, the documen- tary Pandemic: Facing AIDS () and the romantic comedy The Girl in the Café () come in two very different forms but are clearly meant to be direct inter- ventions in efforts to fight AIDS and global poverty. -

Dennell2011.Pdf (2.222Mb)

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Equality Works: How One Race Equality Centre Conceptualises, Articulates and Performs the Idea of Equality in Scotland Brandi Lee Dennell Submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Social Anthropology University of Edinburgh 2011 Table of Contents Declaration............................................................................................................ iii Acknowledgements............................................................................................. iv Abstract ............................................................................................................... v Abbreviations..................................................................................................... -

FIT NOLA PARTNERSHIP Shared Action Blueprint to Achieve Healthy Weight & Fitness for Everyone in New Orleans New Orleans Let’S Move! City Initiative

FIT NOLA PARTNERSHIP SHARED ACTION BLUEPRINT to Achieve Healthy Weight & Fitness for Everyone in New Orleans New Orleans Let’s Move! City Initiative FIT NOLA PARTNERSHIP | SHARED ACTION BLUEPRINT | PAGE i Table of Contents Executive Summary . 3 Taking Action . 4 Building the Fit NOLA Partnership . 5 Policy and Environmental Change Strategies . 5 Social-Ecological Approach to Partnership . 6 Youth Voice . 7 Vision/Mission/Core Values . 8 Causes of Obesity and Factors Affecting Fitness . 9 Negative Consequences of Obesity and Poor Fitness . 10 Positive Consequences of Healthy Weight and Fitness . 10 New Orleans Fitness Asset Map . 11 • Healthy Eating Assets . 12 • Physical Activity Assets . .. 13 • Comprehensive Assets . 14 Priority Action Strategies . 15 Sector-Based Action Strategies . 15 • Government . 16 • Community . 17 • Early Childhood . 18 • School and Out-of-School Time . .. 19 • Business and Media . 20 • Health Care . 21 Evaluating Our Success . 22 Moving Forward to a Fit NOLA . .. 23 • Partnership Structure . 23 • Implementation . 24 • Next Steps . 24 Acknowledgements . 25 Partner Organizations . 26 References . 28 FIT NOLA PARTNERSHIP | SHARED ACTION BLUEPRINT | PAGE ii A message from Mayor Mitch Landrieu: Congratulations to the Fit NOLA Partnership for the efforts that went into making this Action Blueprint to achieve a fit city possible. The Partnership has proven to be a powerful force as our city addresses the challenge of helping children and families be nutritionally and physically fit. New Orleans has established itself as the nation’s laboratory for innovation and change. We are addressing the toughest problems with new solutions and unprecedented energy. Our health care sector has seen a dramatic transformation. Since Hurricane Katrina, there has been a remarkable evolution of community health care clinics, impending development of three new hospitals and an advanced health information technology infrastructure. -

PN: 1664.012 March 16, 2007

PN: 1664.012 March 16, 2007 ARCHITECTURAL INVESTIGATIONS FOR THE PROPOSED BEECH RIDGE WIND ENERGY FACILITY, GREENBRIER, NICHOLAS, AND POCAHONTAS COUNTIES, WEST VIRGINIA Prepared For: Invenergy LLC 7564 Standish Place, Suite 123 Rockville, Maryland 20855 Prepared By: BHE Environmental, Inc. 11733 Chesterdale Road Cincinnati, Ohio 45246 & Gray & Pape, Inc. 1705 E. Main Street Richmond, Virginia 23223 (804) 644-0656 Patrick O’Bannon Senior Manager Lena L. Sweeten Senior Principal Investigator ______________________________ Patrick O’Bannon Senior Manager Notice: This report has been prepared by BHE Environmental, Inc., solely for the benefit of its client in accordance with an approved scope of work. BHE assumes no liability for the unauthorized use of this report or the information contained in it by a third party. Copyright © 2007 BHE Environmental, Inc. ABSTRACT Invenergy LLC has contracted BHE Environmental, Inc. with to undertake a historic architectural survey for the proposed Beech Ridge Wind Energy Facility in Greenbrier County, West Virginia. BHE has requested though its subcontractors at Gray and Pape, Inc. that a historic architecture survey be conducted to inventory all above-ground cultural resources, including updating previously inventoried properties within the Area of Potential Effect. For the purpose of this investigation, the project’s Area of Potential Effect is broadly defined as extending 5 miles around the locations of the proposed wind turbines (approximately 165,000 acres or 258 square miles). The project Area of Potential Effect encompasses areas within Greenbrier, Nicholas, and Pocahontas counties, West Virginia. The wind turbine facility is proposed to be located along Beech Ridge in northern Greenbrier County, on land to be leased primarily from the MeadWestvaco Corporation. -

Building and Implementing Healthy Food Services Building and Implementing Healthy Food Services

Building and Implementing healthy food services building and implementing healthy food services Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 3 ASSESSING THE NEEDS AND OPPORTUNITIES 5 IMPLEMENTATION: FOOD SERVICE GUIDELINES 8 PROCUREMENT 8 BUSINESS PL ANNING 10 IMPLEMENTATION AND MARK E TING 13 PRODUC T 13 PRICING 19 PROMOTION 2 0 PLACEMENT 21 IMPLEMENTATION: POLICIES 22 SUPPORTIVE STRATEGIES 24 E VALUATING HE ALTHY FOOD SERVICES 25 CONCLUSION 28 APPENDIX: SAMPLE POLICIES 29 GLOSSARY 31 REFERENCES 31 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 32 - 2 - building and implementing healthy food services Introduction Food services make food and beverages available to purchase in almost all of the places where we spend our days, including at work, in school, at the park and at other points where daily activities take place. Meals and snacks are increasingly being purchased and consumed away from home. With overweight and obesity rates at an all-time high in the United States, both the public and private sectors are beginning to critically examine their role in the problem and are taking action to address the solution by helping to create a healthier food environment for their workforce and residents. Creating healthy food service policies and programs are promising strategies to improving health through the food environment. This approach closely aligns with Institute of Medicine recommendations to accelerate progress in addressing the obesity epidemic by working to create environments where healthy food and beverage options are the easy choice.i - 3 - building and implementing healthy food services Public and private sector institutions are beginning to think about how they CONCESSIONS AT A GLANCE can increase access to healthy food and beverage options sold or served in Focusing on healthy food services is their facilities. -

Rethink Your Drink Healthy Beverage Toolkit for Healthcare

Rethink Your Drink Healthy Beverage Toolkit for Healthcare 1 This toolkit is a resource of the Illinois Public Health Institute (IPHI), developed in collaboration with Health Care Without Harm (HCWH) and the American Heart Association (AHA) for Illinois hospitals and health care institutions interested in reducing consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. It was made possible by funding through the Department of Health and Human Services: Communities Putting Prevention to Work (CPPW) grant. CPPW is a joint project of the Cook County Department of Public Health and the Public Health Institute of Metropolitan Chicago. The Boston Public Health Commission Healthy Beverage Toolkit was utilized with permission in the development of this resource for hospitals. 2 Rethink Your Drink Healthy Beverage Toolkit for Healthcare In May, 2011, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a report Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation that shared recommendations and strategies for reversing the obesity epidemic in the United States. One of the goals is to “create food and beverage environments that ensure that healthy food and beverage options are the routine, easy choice.”1 "Five multi-faceted strategies are related to this goal. One calls for “decision makers in the business community/private sector, in nongovern- mental organizations and at all levels of government” to “adopt comprehensive strategies to reduce over- consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages.”2 Illinois Public Health Institute The Illinois Public Health Institute (IPHI) works through partnerships to promote prevention and improve public health systems that maximize health and quality of life for the people of Illinois. While acknowledg- ing the impact of individual choices on health outcomes, IPHI focuses on policy, systems and environments and their role in supporting good choices or presenting barriers to health.