A Horse: Macdonald's Theodicy in at the Back of the North Wind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Checklist of George Macdonald's Books Published in America, 1855-1930

North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies Volume 39 Article 2 1-1-2020 A Checklist of George MacDonald's Books Published in America, 1855-1930 Richard I. Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind Recommended Citation Johnson, Richard I. (2020) "A Checklist of George MacDonald's Books Published in America, 1855-1930," North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies: Vol. 39 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind/vol39/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Checklist of George MacDonald Books Published in America, 1855-1930 Richard I. Johnson Many of George MacDonald’s books were published in the US as well as in the United Kingdom. Bulloch and Shaberman’s bibliographies only provide scanty details of these; the purpose of this article is to provide a more accurate and comprehensive list. Its purpose is to identify each publisher involved, the titles that each of them published, the series (where applicable) within which the title was placed, the date of publication, the number of pages, and the price. It is helpful to look at each of these in more detail. Publishers About 50 publishers were involved in publishing GMD books prior to 1930, although about half of these only published one title. -

Memorial Review of “George Macdonald: a Study of Two Novels.” by William Webb, Part of Volume 11 of Romantic Reassessment

Memorial review of “George MacDonald: A Study of Two Novels.” by William Webb, part of volume 11 of Romantic Reassessment. Salzburg, 1973. Deirdre Hayward illiam Webb’s aim in this study is to examine two “rather neglected”W novels of George MacDonald in order to bring out “what is most characteristic in them of the author’s undoubted genius” (105). He sets out to demonstrate that Mary Marston is “a capable piece of fiction” (58), and his discussion of Home Again, though brief, brings out several interesting features of the novel. I have chosen to comment on aspects of his study which give the reader fresh insights, and illuminate less well-known areas of MacDonald’s writing. The study itself is rather loosely structured, with the plan and links between the topics not always clear; and it is frustrating that Webb almost never gives sources for the many quoted passages, and often drops in references—for example a comparison with Dickens in Hard Times or Our Mutual Friend—without any supporting detail to contextualise his comments. Having said this, I found myself impressed by many of the issues discussed, and interested in the directions (sometimes quite obscure and fascinating) in which he points the reader. Additionally, his exploration of some of the literary sources and artistic relationships recognisable in Mary Marston contribute with some authority to MacDonald scholarship. Webb recognises the influence of seventeenth-century English literature on Mary Marston (1881), and observes that in chapter 11, “William Marston,” where Mary’s father, the saintly William Marston, dies, the theme of poetry is related to the plot (83). -

149 44583960-16E7-404F-A82c

Penguin Readers Factsheets l e v e l E T e a c h e r’s n o t e s 1 2 3 Black Beauty 4 5 by Anna Sewell 6 ELEMENTARY S U M M A R Y ublished in 1877, Black Beauty is one of literature’s for those in less fortunate circumstances. This also included P best-loved classics and is the only book that Anna the animals that shared their lives. In Victorian England, Sewell ever wrote. Four films of the book have been horses were used in industry, and were often treated badly. made, the most recent in 1994. Anna and her mother were appalled if they saw a horse being In the book, Black Beauty, a horse, tells the story of his life mistreated and often showed their disapproval to the horse’s in his own words. It is a story of how he was treated with owner. kindness and love when he was young, but how his When she was fourteen, Anna suffered a fall in which she treatment changed at the hands of different owners: some injured her knee. This never healed and left her unable to were kind and cared for him properly, but others were walk without the help of a crutch. Over the following years, careless or unkind, and this led to illness and injury. Black she became increasingly disabled. However, she learnt to Beauty spent his young life with his mother on Farmer Grey’s drive a horse-drawn carriage and took great pleasure in farm. -

BLACK BEAUTY by Anna SEWELL Illustrated by ^>:*00^^- CECIL ALDIN T

BLACK BEAUTY By anna SEWELL Illustrated by ^>:*00^^- CECIL ALDIN t ,>%, ^'^^^^::?-.. ^1 -I .^-- //I) jy^lA ^/// 7^/- JOHNA.SEAVERNS nrwHi /QJd ; f- BLACK BEAUTY As the sun was going down ... we stopped at the " principal hotel in the market place BLACK BEAUTY THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A HORSE By ANNA SEWELL Illustrated by Eighteen Plates in Colour, specially drawn for this edition by CECIL ALDIN BOOTS THE CHEMISTS BRANCHES EVERYWHERE RECOMMENDED BY THE ROYAL SOCIETY FOR THE PREVENTION OF CRUELTY TO ANIMALS Published by Jarrolds, Publishers^ London, Ltd. for Boots Pure Drug Co., Ltd., Nottingham and Printed by William Brendon & Son, Ltd. Plymouth CONTENTS CHAPTER vi CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE XXIV. Lady Anne, or a Runaway Horse 135 XXV. Reuben Smith 144 XXVI. How IT Ended 150 XXVII. Ruined, and going Downhill 154 XXVIII. A Job Horse and his Drivers 158 XXIX. Cockneys 164 XXX. A Thief 173 XXXI. A Humbug 177 XXXII. A Horse Fair 182 XXXIII. A London Cab Horse 188 XXXIV. An Old War Horse 194 XXXV. Jerry Barker 202 XXXVI. The Sunday Cab 211 XXXVII. The Golden Rule 218 XXXVIII. Dolly and a Real Gentleman 223 XXXIX. Seedy Sam 229 XL. Poor Ginger 235 XLI. The Butcher 238 XLII. The Election 243 XLIII. A Friend in Need 246 XLIV. Old Captain and His Successor 252 XLV. Jerry's New Year 259 XLVI. Jakes and the Lady 268 XLVII. Hard Times 274 XLVIII. Farmer Thoroughgood and His Grandson Willie . 281 XLIX. My Last Home 287 " LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS BY CECIL ALDIN "As THE SUN WAS GOING DOWN ... WE STOPPED AT THE PRINCIPAL HOTEL IN THE MARKET PLACE " Frontispiece PAGR " The first place that I can well remember, was a large pleasant MEADOW with A POND OF CLEAR WATER IN IT . -

Volume 1 a Collection of Essays Presented at the First Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on C.S

Inklings Forever Volume 1 A Collection of Essays Presented at the First Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on C.S. Lewis & Article 1 Friends 1997 Full Issue 1997 (Volume 1) Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1997) "Full Issue 1997 (Volume 1)," Inklings Forever: Vol. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever/vol1/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis & Friends at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inklings Forever by an authorized editor of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INKLINGS FOREVER A Collection of Essays Presented at tlte First FRANCES WHITE EWBANK COLLOQUIUM on C.S. LEWIS AND FRIENDS II ~ November 13-15, 1997 Taylor University Upland, Indiana ~'...... - · · .~ ·,.-: :( ·!' '- ~- '·' "'!h .. ....... .u; ~l ' ::-t • J. ..~ ,.. _r '· ,. 1' !. ' INKLINGS FOREVER A Collection of Essays Presented at the Fh"St FRANCES WHITE EWBANK COLLOQliTUM on C.S. LEWIS AND FRIENDS Novem.ber 13-15, 1997 Published by Taylor University's Lewis and J1nends Committee July1998 This collection is dedicated to Francis White Ewbank Lewis scholar, professor, and friend to students for over fifty years ACKNOWLEDGMENTS David Neuhauser, Professor Emeritus at Taylor and Chair of the Lewis and Friends Committee, had the vision, initiative, and fortitude to take the colloquium from dream to reality. Other committee members who helped in all phases of the colloquium include Faye Chechowich, David Dickey, Bonnie Houser, Dwight Jessup, Pam Jordan, Art White, and Daryl Yost. -

Tyler Street Christian Academy by Virginia Hamilton Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea SUGGESTED SUMMER READING LIST Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm by Kate D

Tyler Street Christian Academy by Virginia Hamilton Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea SUGGESTED SUMMER READING LIST Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm by Kate D. Wiggin by Jules Verne In addition to the required summer reading, Ride the West Wind by Barbara Chamber West Side Story by Leonard Bernstein the following is a list of suggested reading The Sea Wolf by Jack London Wolf Rider by Avi material for your student. It is a proven fact that The Secret Garden by Francis Burnett Yo Soy Joaquin by Rodolfo Gonzales reading comprehension increases and Secret of The Andes by Ann Nolan Clark achievement test and SAT scores improve the Sixth Grade Can Really Kill You by Barthe DeClements HIGH SCHOOL – 11th and 12th GRADE more a student reads. This list, created using a Song of The Trees and other titles by Mildred Taylor Andromeda Strain by Michael Crichton number of different sources, is comprised of Sounder by William H. Armstrong Catch 22 by Joseph Heller appropriate grade level material and various Christy by Catherine Marshall interest areas. Have a wonderful summer and Summer of the Swans by Betsy Byars enjoy a good book! Swiss Family Robinson by Johann David Wyss Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court A Taste of Blackberries by Doris Buchanan Smith by Mark Twain The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas The Death of a Cruz by Carlos Fuentes Treasure Island by Robert Lewis Stevenson Frankenstein by Mary Shelley Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt Gifted Hands by Ben Carson th th MIDDLE SCHOOL – 6 - 8 GRADE The View from Saturday by E. -

Classic Reads Sarah, Plain and Tall Series Little Women by Patricia Mclachlan (JF MCL) by Louisa May Alcott (JF ALC) Winnie the Pooh Series Peter Pan by A

Classic Reads Sarah, Plain and Tall series Little Women by Patricia McLachlan (JF MCL) by Louisa May Alcott (JF ALC) Winnie the Pooh series Peter Pan by A. A. Milne (JF MIL) by J. M. Barrie (JF BAR) Anne of Green Gables The Wizard of Oz by L. M. Montgomery (JF MON) by Frank L. Baum (JF BAU) Rascal A Bear Called Paddington by Sterling North (J92 North) by Michael Bond (JF BON) Pollyanna The Secret Garden by Eleanor Porter (JF POR) by Frances Hodgson Burnett (JF BUR) The Adventures of Robin Hood A Little Princess by Howard Pyle (JF PYL) by Frances Hodgson Burnett (JF BUR) (retold by John Burrows) The Incredible Journey The Little Prince by Sheila Burnford (JF BUR) by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (JF SAI) Alice's Adventures in Wonderland Black Beauty by Lewis Carroll (JF CAR) by Anna Sewell (JF SEW) The Wind in the Willows Treasure Island by Kenneth Grahame (JF GRA) by Robert Lewis Stevenson (JF STE) (retold by Chris Tait) Misty of Chincoteague series by Marguerite Henry (JF HEN) All-of-a-Kind Family by Sydney Taylor (JF TAY) Babe : the Gallant Pig by Dick King-Smith (JF KIN) Mary Poppins by P. L. Travers (JF TRA) The Jungle Book: The Mowgli Stories by Rudyard Kipling (JF KIP) 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne (JF VER) The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe series (retold by Lisa Church) by C. S. Lewis (JF LEW) Stuart Little Pippi Longstocking series by E. B. White (JF WHI) by Astrid Lindgren (JF LIN) Little House on the Prairie series White Fang by Laura Ingalls Wilder (JF WIL) by Jack London (JF LON) Swiss Family Robinson The Call of the Wild by Johann David Wyss (JF WYS) by Jack London (JF LON) www.phplonline.org 262-246-5182 . -

Download Transition Book List

Transition Booklist July 2020 E-Books All these e-books are available to borrow for free through Coventry Public libraries. Just click on the book you want to read, and you will be taken to the right page on their Borrowbox website. If you already have a library card you just need to have the number from your card and your pin number. If you don’t have a library card, then don’t worry you can register online at www.coventry.gov.uk/joinalibrary and once you have been sent your new library card number you will be able to start borrowing. Transition books Ella on the outside by Cath Howe The Weight of water by Sarah Crossan Completely Cassidy: Accidental Genius by Tamsyn Murray My best friend and other enemies by Catherine Wilkins Girl 38 by Ewa Jozefkowicz PSHE books The Taylor Turbochaser by David Baddiel Clownfish by Alan Durant Check Mates by Stewart Foster Boy 87 by Ele Fountain Fantasy and Adventure books Storm Keepers island by Catherine Doyle The Middler by Kirsty Applebaum Malamander by Thomas Taylor The Fowl twins by Eoin Colfer The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman Pog by Padraig Kenny Evernight by Ross McKenzie Cloudburst by Wilbur Smith Rumble Star by Abi Elphinstone The House of Chicken Legs by Sophie Anderson Percy Jackson and the lightning Thief Heroes of the Valley by Jonathan Stroud The land of Neverendings by Kate Saunders Asha & the spirit bird by Jasbinder Bilan A place called perfect by Helena Duggan The 1,000-year-old boy by Ross Welford The infinite lives of Maisy Day by Christopher Edge Historical The skylarks war by Hilary McKay Make more noise by various authors The boy who flew by Fleur Hitchcock Classics The Hobbit by J.R.R. -

Sussex Archceological Society Newsletter

Sussex Archceological Society Newsletter Seven Edited by John Farrant. 27 Bloomsbury Place. Brighton. BN2 1 DB Brighton 686578 September 1972 Published by the Society at Barbican House. Lewes ANNUAL GENERAL MEETINGS spent the afternoon planting potatoes. Perhaps our The Annual General Meetings of the Society and of the Annual General Meeting was like this, a recovering and Trust were held in Lewes on Saturday, 8 April 1972. The also a planting operation? What we did for the new reports of the Councils and the accounts were adopted. generation was important. We had to mediate between The officers of the Society were re-elected, as were seven t he generations. His son aged eight years old had missed, of the eight retiring members of the Council; Mr. G. H. to his great disappointment a visit by his class to Fish Kenyon did not stand for re -election, and Mr. C. E. Brent bourne, and he knew what a very real sense of excite was elected. The auditors were re-appointed . The Presi ment was felt by young children about the past, even dent of the Society gave a brief address which is sum before they had a real sense of time. marised below. In the afternoon, the meeting reassembled Mr. Farrant's Newsletter had been published only for a for a lecture by Dr. Audrey Baker on 'Early Romanesque short time, but the President said he hoped members Wall Paintings in Sussex'. would respond to the appeal for news. On his re-election as President Professor Asa Briggs said Professor Briggs ended by saying that he deeply appreci that he valued the link of the Society with the University ated the invitation to serve again as President, and he and also valued it personally as a resident of Lewes and would do his best to discharge his responsibilities during as a historian. -

The Armstrong Browning Library's George Macdonald Collection Cynthia Burgess

North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies Volume 31 Article 2 1-1-2012 The Armstrong Browning Library's George MacDonald Collection Cynthia Burgess Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind Recommended Citation Burgess, Cynthia (2012) "The Armstrong Browning Library's George MacDonald Collection," North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies: Vol. 31 , Article 2. Available at: http://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind/vol31/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ARMSTRONG BROWNING LIBRARY’S GEORGE MACDONALD COLLECTION Cynthia Burgess he Armstrong Browning Library (ABL) of Baylor University is a nineteenth-centuryT research center committed to a focus on the British-born poets Robert Browning (1812-89) and Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-61). Because of the Brownings’ stature in the literary world of nineteenth-century Britain and America, they became acquainted with most of the famous writers of their era and developed personal friendships with many. Alfred Tennyson, Matthew Arnold, Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin, Charles Dickens, Joseph Milsand, Isa Blagden, James Russell Lowell, and Harriet Beecher Stowe were only a few of their intimate friends and correspondents. Over the years, the ABL has broadened its collecting focus to include these and other associated nineteenth-century writers, including George MacDonald, as well as resources that reflect broader aspects of nineteenth-century literature and culture. -

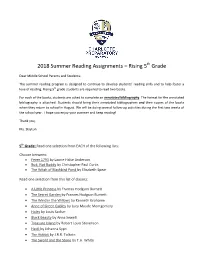

2018 Summer Reading Assignments – Rising 5 Grade

2018 Summer Reading Assignments – Rising 5th Grade Dear Middle School Parents and Students: The summer reading program is designed to continue to develop students’ reading skills and to help foster a love of reading. Rising 5th grade students are required to read two books. For each of the books, students are asked to complete an annotated bibliography. The format for the annotated bibliography is attached. Students should bring their annotated bibliographies and their copies of the books when they return to school in August. We will be doing several follow-up activities during the first two weeks of the school year. I hope you enjoy your summer and keep reading! Thank you, Ms. Slayton 5th Grade: Read one selection from EACH of the following lists: Choose between: Fever 1793 by Laurie Halse Anderson Bud, Not Buddy by Christopher Paul Curtis The Witch of Blackbird Pond by Elizabeth Spear Read one selection from this list of classics: A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame Anne of Green Gables by Lucy Maude Montgomery Holes by Louis Sachar Black Beauty by Anna Sewell Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson Heidi by Johanna Sypri The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkein The Sword and the Stone by T.H. White Annotated Bibliography Students must complete an annotated bibliography for each book that they read for summer reading. This may be typed or neatly handwritten on notebook paper. 1. Title 2. Author 3. Genre (nonfiction, historical fiction, fiction, fantasy, etc.) 4. -

The Meaning of 'Black Beauty' As Seen in Anna Sewell's

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI THE MEANING OF ‘BLACK BEAUTY’ AS SEEN IN ANNA SEWELL’S BLACK BEAUTY A SARJANA PENDIDIKAN FINAL PAPER Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English Language Education By Wening Putri Pertiwi Student Number: 121214007 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2017 i PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI iii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI STATEMENT OF WORK’S ORIGINALITY I honestly declare that this final paper, which I have written, does not contain the work or parts of the work of other people, expect those cited in the quotations and the references, as a scientific paper should. Yogyakarta, October 2, 2017 The Writer Wening Putri Pertiwi 121214007 iv PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PEPRSETUJUAN PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH UNTUK KEPENTINGAN AKADEMIS Yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma: nama : Wening Putri Pertiwi nomor mahasiswa : 121214007 Demi pengembangan ilmu pengetahuan, saya memberikan kepada Perpustakan Universitas Sanata Dharma karya ilmiah saya yang berjudul: THE MEANING OF ‘BLACK BEAUTY’ AS SEEN IN ANNA SEWELL’S BLACK BEAUTY Dengan demikian saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma hak untuk menyimpan, mengalihkan dalam bentuk media lain, mengelolanya dalam betuk pangkalan data, mendistribusikan secara terbatas, dan mempublikasikannya di internet atau media lain untuk kepentingan akademis tanpa perlu meminta izin dari saya maupun memberikan royalti kepada saya selama tetap mencantumkan nama saya sebagai penulis. Demikian pernyataan ini saya buat dengan sebenarnya.