Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Merchant, Jimmy Merchant, Jimmy

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Oral Histories Bronx African American History Project 4-7-2006 Merchant, Jimmy Merchant, Jimmy. Interview: Bronx African American History Project Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/baahp_oralhist Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Merchant, Jimmy. 7 April 2006. Interview with the Bronx African American History Project. BAAHP Digital Archive at Fordham. This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the Bronx African American History Project at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oral Histories by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interviewee: Jimmy Merchant Interviewers: Alessandro Buffa, Loreta Dosorna, Dr. Brian Purnell, and Dr. Mark Naison Date: April 7, 2006 Transcriber: Samantha Alfrey Mark Naison (MN): This is the 154th interview of the Bronx African American History Project. We are here at Fordham University on April 7, 2006 with Jimmy Merchant, an original and founding member of Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, who has also had a career as an artist. And with us today, doing the interviews, are Alessandro Buffa, Lorreta Dosorna, Brian Purnell, and Mark Naison. Jimmy, can you tell us a little about your family and where they came from originally? Jimmy Merchant (JM): My mom basically came from Philadelphia. My dad – his family is from the Bahamas. He – my dad – was shifted over to the south as a youngster. His mother was from the Bahamas and she moved into the South – South Carolina, something like that – and he grew up there. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Stanley Turrentine Don't Mess with Mister T. Mp3, Flac, Wma

Stanley Turrentine Don't Mess With Mister T. mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Don't Mess With Mister T. Country: US Released: 1973 Style: Soul-Jazz, Cool Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1358 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1936 mb WMA version RAR size: 1670 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 142 Other Formats: DXD RA AU DTS DMF WAV TTA Tracklist Hide Credits Don't Mess With Mister T. A1 9:50 Written-By – Marvin Gaye Two For T. A2 5:28 Written-By – Stanley Turrentine Too Blue B1 7:20 Written-By – Stanley Turrentine I Could Never Repay Your Love B2 8:00 Written-By – Bruce Hawes Companies, etc. Record Company – Creed Taylor, Inc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Creed Taylor, Inc. Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Mastered At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Pressed By – Columbia Records Pressing Plant, Terre Haute Published By – Jobete Music Co., Inc. Published By – Twentieth Century Music Corp. Published By – Carlipam Music, Inc. Published By – Mighty Three Music Credits Alto Saxophone – Jerry Dodgion Baritone Saxophone – Pepper Adams Bass – Ron Carter Bass Trombone – Alan Raph Cello – George Ricci, Seymour Barab Conductor, Arranged By – Bob James Design – Bob Ciano Drums – Idris Muhammad Electric Piano – Bob James (tracks: A1), Harold Mabern (tracks: A2, B1) Engineer – Rudy Van Gelder Flugelhorn, Trumpet – John Frosk, Randy Brecker Guitar – Eric Gale Mastered By – RVG* Organ – Richard Tee (tracks: A1, B1, B2) Percussion – Rubens Bassini Photography By [Cover] – Alen MacWeeney Photography By [Liner] – Mort Mace Piano – Bob James (tracks: A1, B1, B2) Producer – Creed Taylor Tenor Saxophone – Joe Farrell, Stanley Turrentine Viola – Emanuel Vardi, Harold Coletta Violin – David Nadien, Emanuel Green, Guy Lumia, Harold Kohon, Harry Cykman, Harry Glickman, Irving Spice, John Pintaualle* Notes Label variation, no 'Side A / Side B' on labels, differs from this version. -

Wszystkie 2012

30/12/2012 [ Radio RAM ] === MOONDOG / Bird's Lament [DJAZZ (12")] QUANTIC SOUL ORCHESTRA / Get A Move On [Ubiquity (LP)] GENE HARRIS w/ The Three Sounds / Eleanor Rigby [Blue Note/Dusty Groove (LP)] EDDIE JEFFERSON / Thank You Falletinme Be Mice Elf Again [Muse (LP)] WAR / Freight Train Jam [Far Out Productions (LP)] JESTOFUNK f/ Ce Ce Rogets & Fred Wesley / The Ghetto [Irma (EP)] ROLF KUEHN GROUP / 66 Park Avenue [Sonorama (7")] TIM, GARY & ROMEO / Sex Machine (Getting' Up And Doin' Out Thang) [777/Funk Night (7")] TIM, GARY & ROMEO / 777 [777/Funk Night (7")] DOKKERMAN & THE TURKEING FELLAZ / Broken [Budabeats/Tramp (7")] DOKKERMAN & THE TURKEING FELLAZ / Plan B [Budabeats/Tramp (7")] WISDOM & SLIME f/ Werd / Empty Handed (instrumental + vocal) [Goalgetter Austria (EP)] BIZARRE TRIBE / Tour Guide [Gummy Soul (LP)] BIZARRE TRIBE / Runnin' [Gummy Soul (LP)] BIZARRE TRIBE / Ya mama and stuff [Gummy Soul (LP)] BIZARRE TRIBE / Soul Flower (We've Got) [Gummy Soul (LP)] BIZARRE TRIBE / Bonita Keeps On Passin' Me By [Gummy Soul (LP)] BIZARRE TRIBE / Otha Otha Fish [Gummy Soul (LP)] BIZARRE TRIBE / 4 Better Or 4 Worse [Gummy Soul (LP)] BIZARRE TRIBE / Award Tour Guide [Gummy Soul (LP)] BIZARRE TRIBE / Trust, Pt. II [Gummy Soul (LP)] BIZARRE TRIBE / It Ain't Nothing Like [feat. Kriminul] [Gummy Soul (LP)] BIZARRE TRIBE / Lyrics To Let It Go [Gummy Soul (LP)] BIZARRE TRIBE / Doin' Time [feat. Sublime w/ The Pharcyde] [Gummy Soul (LP)] BIZARRE TRIBE / Pharcyde Of The Moon [feat. Bizarre Tribe w/ Black Moon] [Gummy Soul (LP)] FELA SOUL / Stakes -

Indigo in Motion …A Decidedly Unique Fusion of Jazz and Ballet

A Teacher's Handbook for Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre's Production of Indigo in Motion …a decidedly unique fusion of jazz and ballet Choreography Kevin O'Day Lynne Taylor-Corbett Dwight Rhoden Music Ray Brown Stanley Turrentine Lena Horne Billy Strayhorn Sponsored by Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre's Arts Education programs are supported by major grants from the following: Allegheny Regional Asset District Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation Pennsylvania Council on the Arts The Hearst Foundation Sponsoring the William Randolph Hearst Endowed Fund for Arts Education Additional support is provided by: Alcoa Foundation, Allegheny County, Bayer Foundation, H. M. Bitner Charitable Trust, Columbia Gas of Pennsylvania, Dominion, Duquesne Light Company, Frick Fund of the Buhl Foundation, Grable Foundation, Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield, The Mary Hillman Jennings Foundation, Milton G. Hulme Charitable Foundation, The Roy A. Hunt Foundation, Earl Knudsen Charitable Foundation, Lazarus Fund of the Federated Foundation, Matthews Educational and Charitable Foundation,, McFeely-Rogers Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation, William V. and Catherine A. McKinney Charitable Foundation, Howard and Nell E. Miller Foundation, The Charles M. Morris Charitable Trust, Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development, The Rockwell Foundation, James M. and Lucy K. Schoonmaker Foundation, Target Corporation, Robert and Mary Weisbrod Foundation, and the Hilda M. Willis Foundation. INTRODUCTION Dear Educator, In the social atmosphere of our country, in this generation, a professional ballet company with dedicated and highly trained artists cannot afford to be just a vehicle for public entertainment. We have a mission, a commission, and an obligation to be the standard bearer for this beautiful classical art so that generations to come can view, enjoy, and appreciate the significance that culture has in our lives. -

A Music Critic on His First Love, Which Was Reading

them over, and get its mitts on record distribution in the bargain. Nor is it all about the Benjamins. If by popular music you mean domestic palliatives from “Home Sweet to Celine Dion, OK, that’s another realm. But most of what’s now played in concert halls and honored at the Kennedy Center has its roots in antisocial impulses—in a carpe diem hedonism that is a way of life for violent men with money to burn who know damn well they’re destined for prison or the morgue. Most music books assume or briefly acknowledge these inconvenient facts when they don’t ignore them altogether. But they’re central to two recent histories and two recent memoirs, all highly recommended. Memphis-based Preston Lauterbach’s The Chitlin’ Circuit and the Roots of Rock ’n’ Roll For anyone who cares about the history of pop—and also, in a better world, anyone relishes the criminal origins of a mostly southern black club scene from the early ’30s to who cares about the history of the avant-garde—Between Montmartre and the Mudd the late ’60s. Journalist-bizzer Dan Charnas’s history of the hip-hop industry, The Big has a big story to tell. Popular music is generally identified with the rise of Payback, steers clear of much small-timeClub thuggery and leaves brutal LA label boss Suge Knight to Ronin Ro’s Have Gun, Willsong Travel, publishing butROBERT plenty and of piano crime manufacture stories rise up inas theprofits mid-nineteenth century. But starting snowball. Ice-T’s Ice devotes twenty-fivein the 1880s, steely artists pages toand the other lucrative fringe-dwelling heisting operation weirdos have been active as pop the rapper-actor ran before he madeperformers, music his composers, job. -

Eddie Who? - Eddie Harris Amerikansk Tenorsaxofonist, Født 20.10.1934 I Chicago, IL, D

Eddie Who? - Eddie Harris Amerikansk tenorsaxofonist, født 20.10.1934 i Chicago, IL, d. 5.11.1996 Sanger og pianist som barn i baptistkirker og spillede senere vibrafon og tenorsax. Debuterede som pianist med Gene Ammons før universitetsstudier i musik. Spillede med bl.a. Cedar Walton i 7. Army Symphony Orchestra. Fik i 1961 et stort hit og jazzens første guldplade med filmmelodien "Exodus", hvad der i de følgende år gav ham visse problemer med accept i jazzmiljøet. Udsendte 1965 The in Sound med bl.a. hans egen komposition Freedom Jazz Dance, som siden er indgået i jazzens standardrepertoire. Spillede fra 1966 elektrificeret saxofon og hybrider af sax og basun. Flirtede med rock på Eddie Harris In the UK (Atlantic 1969). Spillede 1969 på Montreux festivalen med Les McCann (Swiss Movement, Atlantic) og skrev 1969-71 musik til Bill Cosbys tv-shows. Spillede i 80'erne med bl.a. Tete Montoliu og Bo Stief (Steps Up, SteepleChase, 1981) og igen med Les McCann. Som sideman med bl.a. Jimmy Smith, Horace Silver, Horace Parlan og John Scofield (Hand Jive, Blue Note, 1993). Optrådte trods sygdom, så sent som maj 1996. Indspillede et stort antal plader for mange selskaber, fra 80'erne mest europæiske. Med udgangspunkt i bopmusikken udviklede Harris sine eksperimenter til en meget personlig stil med umiddelbart genkendelig, egenartet vokaliserende tone, fra 70'erne krydret med (ofte lange), humoristisk filosofisk/satiriske enetaler. Følte sig ofte underkendt som musiker og satiriserede over det i sin "Eddie Who". Kilde: Politikens Jazz Leksikon, 2003, red. Peter H. Larsen og Thorbjørn Sjøgren There's a guys (Chorus) You ought to know Eddie Harris .. -

Santa Anita Derby

$$750,0001,0000,000 SANTA ANITA HANDICAP SANTA ANITA DERBY GAME ON DUDE Dear Member of the Media: Now in its 78th year of Thoroughbred racing, Santa Anita is proud to have hosted many of the sport’s greatest moments. Although the names of its historic human and horse heroes may have changed in the SANTA ANITA HANDICAP past seven decades of racing, Santa Anita’s prominence in the sport $1,000,000 Guaranteed (Grade I) remains constant. Saturday, March 7, 2015 • Seventy-Eighth Running This year, Santa Anita will present the 78th edition of one of rac- Gross Purse: $1,000,000 Winner’s Share: $600,000 Other Awards: $200,000 second; $120,000 third; $50,000 fourth; $20,000 fifth ing’s premier races — the $1,000,000 Santa Anita Handicap on Saturday, Distance: One and one-quarter miles on the main track March 7. Nominations: Close February 21, 2015 at $100 each The historic Big ‘Cap was the nation’s first continually run $100,000 Supplementary nominations of $25,000 by 12 noon, Feb. 28, 2015 Track and American stakes race and has arguably had more impact on the progress of Dirt Record: 1:57 4/5, Spectacular Bid, 4 (Bill Shoemaker, 126, February 3, Thoroughbred racing than any other single event in the sport. The 1980, Charles H. Strub Stakes) importance of this race and many of its highlights are detailed by the Stakes Record: 1:58 3/5, Affirmed, 4 (Laffit Pincay Jr., 128, March 4, 1979) Gates Open: 10:00 a.m. esteemed sports journalist John Hall beginning on page 2. -

Country Christmas ...2 Rhythm

1 Ho li day se asons and va ca tions Fei er tag und Be triebs fe rien BEAR FAMILY will be on Christmas ho li days from Vom 23. De zem ber bis zum 10. Ja nuar macht De cem ber 23rd to Ja nuary 10th. During that peri od BEAR FAMILY Weihnach tsfe rien. Bestel len Sie in die ser plea se send written orders only. The staff will be back Zeit bitte nur schriftlich. Ab dem 10. Janu ar 2005 sind ser ving you du ring our re gu lar bu si ness hours on Mon- wir wie der für Sie da. day 10th, 2004. We would like to thank all our custo - Bei die ser Ge le gen heit be dan ken wir uns für die gute mers for their co-opera ti on in 2004. It has been a Zu sam men ar beit im ver gan ge nen Jahr. plea su re wor king with you. BEAR FAMILY is wis hing you a Wir wünschen Ihnen ein fro hes Weih nachts- Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. fest und ein glüc kliches neu es Jahr. COUNTRY CHRISTMAS ..........2 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................86 COUNTRY .........................8 SURF .............................92 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............25 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............93 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......25 PSYCHOBILLY ......................97 WESTERN..........................31 BRITISH R&R ........................98 WESTERN SWING....................32 SKIFFLE ...........................100 TRUCKS & TRAINS ...................32 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............100 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................33 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........33 POP.............................102 COUNTRY CANADA..................33 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................108 COUNTRY -

Of ABBA 1 ABBA 1

Music the best of ABBA 1 ABBA 1. Waterloo (2:45) 7. Knowing Me, Knowing You (4:04) 2. S.O.S. (3:24) 8. The Name Of The Game (4:01) 3. I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do (3:17) 9. Take A Chance On Me (4:06) 4. Mamma Mia (3:34) 10. Chiquitita (5:29) 5. Fernando (4:15) 11. The Winner Takes It All (4:54) 6. Dancing Queen (3:53) Ad Vielle Que Pourra 2 Ad Vielle Que Pourra 1. Schottische du Stoc… (4:22) 7. Suite de Gavottes E… (4:38) 13. La Malfaissante (4:29) 2. Malloz ar Barz Koz … (3:12) 8. Bourrée Dans le Jar… (5:38) 3. Chupad Melen / Ha… (3:16) 9. Polkas Ratées (3:14) 4. L'Agacante / Valse … (5:03) 10. Valse des Coquelic… (1:44) 5. La Pucelle d'Ussel (2:42) 11. Fillettes des Campa… (2:37) 6. Les Filles de France (5:58) 12. An Dro Pitaouer / A… (5:22) Saint Hubert 3 The Agnostic Mountain Gospel Choir 1. Saint Hubert (2:39) 7. They Can Make It Rain Bombs (4:36) 2. Cool Drink Of Water (4:59) 8. Heart’s Not In It (4:09) 3. Motherless Child (2:56) 9. One Sin (2:25) 4. Don’t We All (3:54) 10. Fourteen Faces (2:45) 5. Stop And Listen (3:28) 11. Rolling Home (3:13) 6. Neighbourhood Butcher (3:22) Onze Danses Pour Combattre La Migraine. 4 Aksak Maboul 1. Mecredi Matin (0:22) 7. -

Whelp04 (1Ae8/4)

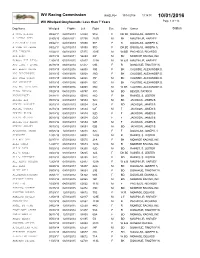

WV Racing Commission WHELP04 10/14/2016 13:14:01 10/01/2016 WV Whelped Greyhounds: Less than 7 Years Page 1 of 114 Dog Name Whelped Eligible Left Right Sex Color Owner Status A COOL BREEZE 09/22/11 02/01/2013 57050 91G F DK BD DOUGLAS, JOSEPH A. A LITTLE IFFY 02/05/10 09/01/2011 52795 210D M BK MAUPIN JR, HARVEY A MIDNIGHT KISS 09/22/11 02/01/2013 57050 91F F R DOUGLAS, JOSEPH A. A TIME TO SHINE 09/22/11 02/01/2013 57050 91D F DK BD DOUGLAS, JOSEPH A. ABE LINCOLN 10/24/11 04/01/2013 57375 101E M W/BEF PACHECO, RICARDO ACE ACER 08/13/10 12/01/2011 54294 80F M BK MONROE RACING, INC ACROSS THE ATLUS 12/08/13 07/01/2015 62817 123H M W & BDMAUPIN JR, HARVEY ACT LIKE U LUVME 05/18/13 08/01/2014 61477 53B F R DONAHUE, TIMOTHY W. ADC BLACK WIDOW 03/13/15 09/01/2016 66008 35B F BK CALISSIE, ALEXANDER D. ADC BLACKMAGIC 03/13/15 09/01/2016 66008 35G F BK CALISSIE, ALEXANDER D. ADC COAL TRAIN 03/13/15 09/01/2016 66008 35F M BK CALISSIE, ALEXANDER D. ADC MIDNIGHT 03/13/15 09/01/2016 66008 35C M BK CALISSIE, ALEXANDER D. ADC MR. ATTITUDE 03/13/15 09/01/2016 66008 35D M W BK CALISSIE, ALEXANDER D. ADIOS AMIGOS 03/20/13 04/01/2015 60757 33C M BD BEVER, PATRICK ADORADANCER 04/14/11 08/01/2012 55915 41D F BK RAINES, S. -

PDF Inventory

Oberlin Conservatory Library Special Collections Milton J. and Mona C. Hinton Collection Inventory of Correspondence Note: If the recipient is Milt Hinton the field is left blank Page | 1 Box Correspondence to Correspondence from Date 1 Hilda Robinson Milt Hinton 1933 1 Oby Allen Milt Hinton 1933-07-11 1 Eddie South 1933-11-24 1 Mary Slaughter 1938-10 1 Mona Hinton 1939-07-14 1 Mona Hinton Milt Hinton 1939-08-20 1 Armando Caballer 1940s 1 DeFranz Williams 1944-03-23 1 Walter "Foots" Thomas 1944-04-17 1 Mona Hinton 1944-04-29 1 Mona Hinton 1944-04-30 1 Keg Johnson 1945[?] 1 Robert Kagan 1945-05-31 1 Walter "Foots" Thomas 1945-11-07 1 Walter "Foots" Thomas 1945-11-21 1 Mona Hinton Milt Hinton 1946-11-29 1 Mona Hinton Milt Hinton 1947-04-23 1 Mona Hinton 1947-07-24 1 Mona Hinton Milt Hinton 1947-11-23 1 Mona Hinton Milt Hinton 1948-03-26 1 Milton Dixon Hinton 1948-04-01 1 Eddie South 1948-08-01 1 Mona Hinton Milt Hinton 1948-10-14 1 J. Van Heurck 1949-01-20 1 Charlotte Hinton Milt Hinton 1950s Oberlin Conservatory Library l 77 West College Street l Oberlin, Ohio 44074 l [email protected] l 440.775.5129 (last updated August 19, 2019) Oberlin Conservatory Library Special Collections Milton J. and Mona C. Hinton Collection Inventory of Correspondence Note: If the recipient is Milt Hinton the field is left blank Page | 2 Box Correspondence to Correspondence from Date 1 Mona Hinton Charlotte Hinton 1950s 1 Mona Hinton Milt Hinton 1950s 1 Mona Hinton Charlotte Hinton 1950s 1 Charlotte Hinton 1950s 1 Mona Hinton 1950s 1 Mona Hinton 1950s