How Do Climate Change Experiments Alter Plot‐

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Lies Beneath 2 FOREWORD

2018 RELEASE THE UNDERSTATEMENT OF EXISTENTIAL CLIMATE RISK BY DAVID SPRATT & IAN DUNLOP | FOREWORD BY HANS JOACHIM SCHELLNHUBER BREAKTHROUGHONLINE.ORG.AU Published by Breakthrough, National Centre for Climate Restoration, Melbourne, Australia. First published September 2017. Revised and updated August 2018. CONTENTS FOREWORD 02 INTRODUCTION 04 RISK UNDERSTATEMENT EXCESSIVE CAUTION 08 THINKING THE UNTHINKABLE 09 THE UNDERESTIMATION OF RISK 10 EXISTENTIAL RISK TO HUMAN CIVILISATION 13 PUBLIC SECTOR DUTY OF CARE ON CLIMATE RISK 15 SCIENTIFIC UNDERSTATEMENT CLIMATE MODELS 18 TIPPING POINTS 21 CLIMATE SENSITIVITY 22 CARBON BUDGETS 24 PERMAFROST AND THE CARBON CYCLE 25 ARCTIC SEA ICE 27 POLAR ICE-MASS LOSS 28 SEA-LEVEL RISE 30 POLITICAL UNDERSTATEMENT POLITICISATION 34 GOALS ABANDONED 36 A FAILURE OF IMAGINATION 38 ADDRESSING EXISTENTIAL CLIMATE RISK 39 SUMMARY 40 What Lies Beneath 2 FOREWORD What Lies Beneath is an important report. It does not deliver new facts and figures, but instead provides a new perspective on the existential risks associated with anthropogenic global warming. It is the critical overview of well-informed intellectuals who sit outside the climate-science community which has developed over the last fifty years. All such expert communities are prone to what the French call deformation professionelle and the German betriebsblindheit. Expressed in plain English, experts tend to establish a peer world-view which becomes ever more rigid and focussed. Yet the crucial insights regarding the issue in question may lurk at the fringes, as BY HANS JOACHIM SCHELLNHUBER this report suggests. This is particularly true when Hans Joachim Schellnhuber is a professor of theoretical the issue is the very survival of our civilisation, physics specialising in complex systems and nonlinearity, where conventional means of analysis may become founding director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate useless. -

Global-Change Controls on Soil-Carbon Accumulation and Loss in Coastal Vegetated Ecosystems

PERSPECTIVE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0435-2 Global-change controls on soil-carbon accumulation and loss in coastal vegetated ecosystems Amanda C. Spivak 1*, Jonathan Sanderman 2, Jennifer L. Bowen 3, Elizabeth A. Canuel 4 and Charles S. Hopkinson1 Coastal seagrass, mangrove and salt-marsh ecosystems—also termed blue-carbon ecosystems—play an important role in the global carbon cycle. Much of the organic carbon they store rests in soils that have accumulated over thousands of years. Rapidly changing climate and environmental conditions, including sea-level rise, warming, eutrophication and landscape development, will impact decomposition and thus the global reservoir of blue soil organic carbon. Yet, it remains unclear how these distur- bances will affect the key biogeochemical mechanisms controlling decomposition—mineral protection, redox zonation, water content and movement, and plant–microbe interactions. We assess the spatial and temporal scales over which decomposition mechanisms operate and how their effectiveness may change following disturbances. We suggest that better integration of decomposition mechanisms into blue-carbon models may improve predictions of soil organic carbon stores and facilitate incor- poration of coastal vegetated ecosystems into global budgets and management tools. lue-carbon ecosystems play an outsized role in the global sediments are saturated, with redox and diffusional gradients, and carbon cycle. They occupy 0.07–0.22% of the Earth’s sur- relatively constant temperature, light and physical conditions. In face and bury 0.08–0.22 PgC yr–1, which is comparable to contrast, soil water content and chemistry vary among blue-carbon B –1 0.2 PgC yr transferred to the seafloor and equivalent to ~10% ecosystems and over intertidal elevation gradients, reflecting local of the entire net residual land sink of 1–2 PgC yr–1 (refs. -

Science Journals

RESEARCH GLOBAL CARBON CYCLE We started our soil warming study in 1991 in an even-aged mixed hardwood forest stand at the Harvard Forest in central Massachusetts (42.54°N, 72.18°W), where the dominant tree Long-term pattern and magnitude of species are red maple (Acer rubrum L.) and black oak (Quercus velutina Lam.). The soil is a soil carbon feedback to the climate stony loam with a distinct organic matter–rich forest floor. (See the supplementary materials system in a warming world for more information on the site’s soils, climate, and land-use history.) The field manipulation contains 18 plots, each J. M. Melillo,1* S.D. Frey,2 K. M. DeAngelis,3 W. J. Werner,1 M. J. Bernard,1 6 × 6 m, that are grouped into six blocks. The F. P. Bowles,4 G. Pold,5 M. A. Knorr,2 A. S. Grandy2 three plots within each block are randomly as- signed to one of three treatments: (i) heated plots In a 26-year soil warming experiment in a mid-latitude hardwood forest, we documented in which the average soil temperature is con- changes in soil carbon cycling to investigate the potential consequences for the climate tinuously elevated 5°C above ambient by the use system. We found that soil warming results in a four-phase pattern of soil organic matter of buried heating cables; (ii) disturbance con- decay and carbon dioxide fluxes to the atmosphere, with phases of substantial soil carbon trol plots that are identical to the heated plots loss alternating with phases of no detectable loss. -

Forest Carbon Assessment for the Green Mountain National Forest 1.0

Forest Carbon Assessment for the Green Mountain National Forest Alexa Dugan ([email protected]), Maria Janowiak ([email protected]) and Duncan McKinley ([email protected]) August 16, 2018 1.0 Introduction Carbon uptake and storage are some of the many ecosystem services provided by forests and grasslands. Through the process of photosynthesis, growing plants remove carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and store it in forest biomass (plant stems, branches, foliage, roots), and much of this organic material is eventually stored in forest soils. This absorption of carbon from the atmosphere (sequestration) helps modulate greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations in the atmosphere. Estimates of net annual storage of carbon indicate that forests in the United States (U.S.) constitute an important carbon sink, removing more carbon from the atmosphere than they are emitting (Pan et al. 2011). Forests in the United States remove the equivalent of about 12-19 percent of annual fossil fuel emissions in the U.S. (EPA 2015, Janowiak et al. 2017). Forests are dynamic systems that naturally undergo fluctuations in carbon storage and emissions as forests establish and grow, die with age or disturbances, and re-establish and regrow. Forests release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere when they die, either through natural aging and competition processes or disturbance events (e.g., combustion from fires), and this process transfers carbon from living carbon pools to dead pools. These dead pools also release carbon dioxide through decomposition or combustion (fires). Management activities include timber harvests, thinning, and fuel reductions treatments that remove carbon from the forest ecosystem and transfer it to the wood products sector. -

Warming Exerts Greater Impacts on Subsoil Than Topsoil CO2 Efflux in A

Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 263 (2018) 137–146 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Agricultural and Forest Meteorology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/agrformet Warming exerts greater impacts on subsoil than topsoil CO2 efflux in a subtropical forest T Weisheng Lina, Yiqing Lia,b, Zhijie Yanga, Christian P. Giardinac, Jinsheng Xiea, Shidong Chena, ⁎ ⁎ Chengfang Lina, , Yakov Kuzyakovd,e,f, Yusheng Yanga, a Key Laboratory for Subtropical Mountain Ecology (Ministry of Science and Technology and Fujian Province Funded), School of Geographical Sciences, Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou 350007, China b College of Agriculture, Forestry and Natural Resource Management, University of Hawaii, Hilo, HI, 96720, USA c Institute of Pacific Islands Forestry, Pacific Southwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service, Hilo, HI, 96720, USA d Department of Soil Science of Temperate Ecosystems, Department of Agricultural Soil Science, University of Gttingen, 37077 Gttingen, Germany e Institute of Physicochemical and Biological Problems in Soil Science, Russian Academy of Sciences, 142290 Pushchino, Russia f Soil Science Consulting, 37077 Gottingen, Germany ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: How warming affects the magnitude of CO2 fluxes within the soil profile remains an important question, with Chinese fir implications for modeling the response of ecosystem carbon balance to changing climate. Information on be- fl CO2 ux lowground responses to warming is especially limited for the tropics and subtropics because the majority of Fine root manipulative studies have been conducted in temperate and boreal regions. We examined how artificial Manipulative warming warming affected CO gas production and exchange across soil profiles in a replicated mesocosms experiment Soil moisture 2 relying on heavily weathered subtropical soils and planted with Chinese fir(Cunninghamia lanceolata). -

Whole Soil Warming Decreases Abundance and Modifies Community Structure of Microorganisms in Subsoil but Not in Surface Soil Cyrill U

https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-2021-14 Preprint. Discussion started: 16 February 2021 c Author(s) 2021. CC BY 4.0 License. Whole soil warming decreases abundance and modifies community structure of microorganisms in subsoil but not in surface soil Cyrill U. Zosso1, Nicholas O.E. Ofiti1, Jennifer L. Soong2, Emily F. Solly3, Margaret S. Torn2, Arnaud Huguet4, Guido L.B. Wiesenberg1 and Michael W.I. Schmidt1 5 1Department of Geography, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland 2Climate and Ecosystem Science Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA 3Group for Sustainable Agroecosystems, Department of Environmental Systems Science, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland 4Sorbonne Université, CNRS, EPHE, PSL, UMR METIS, Paris, France Correspondence to: Cyrill U. Zosso ([email protected]) 10 Abstract. The microbial community composition in subsoils remains understudied and it is largely unknown whether subsoil microorganisms show a similar response to global warming as do microorganisms at the soil surface. Since microorganisms are key drivers of soil organic carbon decomposition, this knowledge gap causes uncertainty in predictions of future carbon cycling in the subsoil carbon pool (>50 % of the soil organic carbon stocks are below 30 cm soil depth). In the Blodgett forest field warming experiment (California, USA) we investigated how +4°C warming the whole soil profile 15 to 100 cm soil depth for 4.5 years has affected the abundance and community structure of microorganisms. We used proxies for bulk microbial biomass carbon (MBC) and functional microbial groups based on lipid biomarkers, such as phospholipid fatty acids (PLFAs) and branched glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers (brGDGTs). -

Carbon Budget of the Harvard Forest Long‐Term Ecological Research Site

Journal: Ecological Monographs Manuscript type: Article Running Head: Carbon cycling in a mid-latitude forest Carbon budget of the Harvard Forest Long-Term Ecological Research site: pattern, process, and response to global change Adrien C. Finzi1, Marc-André Giasson1, Audrey A. Barker Plotkin2,*, John D. Aber3, Emery R. Boose2, Eric A. Davidson4, Michael C., Dietze5, Aaron M. Ellison2, Serita D. Frey3, Evan Goldman6, Trevor F. Keenan7,8, Jerry M. Melillo9, J. William Munger6, Knute J. Nadelhoffer10, Scott V. Ollinger3,11, David A. Orwig2, Neil Pederson2, Andrew D. Richardson12,13, Kathleen Savage14, Jianwu Tang9, Jonathan R. Thompson2, Christopher A. Williams15, Steven C. Wofsy6, Zaixing Zhou11, and David R. Foster2 1 Department of Biology, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts 02215 USA 2 Harvard Forest, Harvard University, Petersham, Massachusetts 01366 USA 3 Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire 03824 USA 4 University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, Appalachian Laboratory, Frostburg, Maryland 21532 USA 5 Department of Earth & Environment, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts 02215 USA 6 School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 USA 7 Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California 94720 USA 8 Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management, UC Berkeley, Berkeley, California 94720 USA 9 The Ecosystems Center, Marine Biological laboratory, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543 USA ThisAccepted Article article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: 10.1002/ECM.1423 This article is protected by copyright. -

Long-Term Pattern and Magnitude of Soil Carbon Feedback to the Climate System in a 2 Warming World

1 Long-term Pattern and Magnitude of Soil Carbon Feedback to the Climate System in a 2 Warming World 3 Authors: J.M. Melillo1*, S.D. Frey2, K.M. DeAngelis3, W.J. Werner1, M.J. Bernard1, F.P. 4 Bowles4, G. Pold5, M.A. Knorr2, A.S. Grandy2 5 Affiliations: 6 1The Ecosystems Center, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA 7 2Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of New Hampshire, Durham, 8 NH 03824, USA 9 3Department of Microbiology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 01003, USA 10 4Research Designs, Lyme, NH 03768, USA 11 5Graduate Program in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, University of Massachusetts, 12 Amherst, MA 01003, USA 13 *Correspondence to: [email protected] 14 Abstract: In a 26-year soil warming experiment in a mid-latitude hardwood forest, we 15 documented changes in soil carbon cycling to investigate the potential consequences for the 16 climate system. We found that soil warming results in a four-phase pattern of soil organic matter 17 decay and carbon dioxide fluxes to the atmosphere, with phases of substantial soil carbon loss 18 alternating with phases of no detectable loss. Several factors combine to affect the timing, 19 magnitude, and thermal acclimation of soil carbon loss. These include depletion of microbially 20 accessible carbon pools, reductions in microbial biomass, a shift in microbial carbon use 21 efficiency, and changes in microbial community composition. Our results support projections of 22 a long-term, self-reinforcing carbon feedback from mid-latitude forests to the climate system as 23 the world warms. -

Global Change and Terrestrial Plant Community Dynamics

Global change and terrestrial plant INAUGURAL ARTICLE community dynamics Janet Franklina,1, Josep M. Serra-Diaza,b, Alexandra D. Syphardc, and Helen M. Regand aSchool of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287; bHarvard Forest, Harvard University, Petersham, MA 01633; cConservation Biology Institute, La Mesa, CA 91941; and dDepartment of Biology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521 This contribution is part of a special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected in 2014. Contributed by Janet Franklin, February 2, 2016 (sent for review October 8, 2015; reviewed by Gregory P. Asner, Monica G. Turner, and Peter M. Vitousek) Anthropogenic drivers of global change include rising atmospheric climatic niches are likely to shift spatially but not how species will concentrations of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses and respond. Models of vegetation dynamics (9), on the other hand, resulting changes in the climate, as well as nitrogen deposition, biotic incorporate effects of multiple, interacting global change agents invasions, altered disturbance regimes, and land-use change. Predict- on terrestrial plant community and species range dynamics. ing the effects of global change on terrestrial plant communities is Scenario-driven forecasts of 21st century global change impacts crucial because of the ecosystem services vegetation provides, from on vegetation cannot be validated without waiting a few decades for climate regulation to forest products. In this paper, we present a changes to happen. These predictions can be informed with a framework for detecting vegetation changes and attributing them to deeper understanding of paleo-vegetation changes (12–14). -

ECI Text and Additional Infos (Annex)

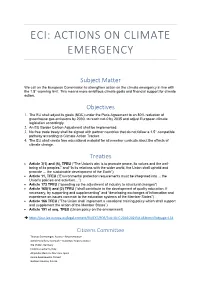

ECI: ACTIONS ON CLIMATE EMERGENCY Subject Matter We call on the European Commission to strengthen action on the climate emergency in line with the 1.5° warming limit. This means more ambitious climate goals and financial support for climate action. Objectives 1. The EU shall adjust its goals (NDC) under the Paris Agreement to an 80% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, to reach net-0 by 2035 and adjust European climate legislation accordingly. 2. An EU Border Carbon Adjustment shall be implemented. 3. No free trade treaty shall be signed with partner countries that do not follow a 1.5° compatible pathway according to Climate Action Tracker. 4. The EU shall create free educational material for all member curricula about the effects of climate change. Treaties • Article 3(1) and (5), TFEU (“The Union's aim is to promote peace, its values and the well- being of its peoples.” and “In its relations with the wider world, the Union shall uphold and promote ... the sustainable development of the Earth”) • Article 11, TFEU (“Environmental protection requirements must be integrated into ... the Union's policies and activities…”) • Article 173 TFEU (“speeding up the adjustment of industry to structural changes”) • Article 165(1) and (2) TFEU (“shall contribute to the development of quality education, if necessary, by supporting and supplementing” and “developing exchanges of information and experience on issues common to the education systems of the Member States”) • Article 166 TFEU (“The Union shall implement a vocational training policy which shall support and supplement the action of the Member States”) • Article 191 et seq. -

Temperature Limitations to Enzyme-Catalyzed Arctic Soil

A Thesis entitled What’s the Holdup? Temperature Limitations to Enzyme-Catalyzed Arctic Soil Decomposition by Ruth Whittington Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Biology ___________________________________________ Michael Weintraub, PhD, Committee Chair ___________________________________________ Daryl Moorhead, PhD, Committee Member ___________________________________________ Patrick Sullivan, PhD, Committee Member ___________________________________________ Cyndee Gruden, PhD, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo August 2019 Copyright 2019, Ruth Whittington This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of What’s the Holdup? Temperature Limitations to Enzyme-Catalyzed Arctic Soil Decomposition by Ruth Whittington Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Biology The University of Toledo August 2019 Arctic ecosystems contain globally important terrestrial carbon stocks, and their temperatures are rising at twice global rates. While increasing temperatures lead to faster decomposition and carbon mineralization rates, predicting the magnitude and future patterns of soil respiration is difficult due to multiple interacting direct and indirect effects. In particular, we lack mechanistic data on how low temperatures impact extracellular enzyme activities and thereby determine carbon supply rates to respiration. For this research, I performed two laboratory soil incubations designed to measure the temperature responses of enzymes catalyzing the terminal steps in Arctic tundra soil organic matter depolymerization. These experiments were designed to first characterize microbial activity responses to temperature based on cumulative carbon loss, and then to identify how substrate and nutrient availability mediate indirect temperature responses. -

A Multi-Disciplinary Perspective to Nuance the Narrative of Tree Planting As A

1 A multi-disciplinary perspective to nuance the narrative of tree planting as a 2 nature-based solution 3 S.M. Vogel1,2*, S. Monsarrat1,2*, M. Pasgaard1,2, R. Buitenwerf1,2, A.C. Custock1,2,3, S. Ceauşu4, W. Li1,2, 4 C.E. Gordon1,2, S. Jarvie1,2,5, J. Mata1,2, E.A. Pearce1,2, J-C. Svenning1,2 5 1Center for Biodiversity Dynamics in a Changing World (BIOCHANGE), Department of Biology, 6 Aarhus University, Ny Munkegade 114, DK-8000 Aarhus C, Denmark 7 2Section for Ecoinformatics and Biodiversity, Department of Biology, Aarhus University, Ny 8 Munkegade 114, DK-8000 Aarhus C, Denmark 9 3Anthropology Department, Aarhus University, Moesgaard Alle 20, 8270 Højbjerg, Denmark 10 4 Centre for Biodiversity and Environment Research, Department of Genetics, Evolution and 11 Environment, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK 12 5 Otago Regional Council, 70 Stafford Street, Dunedin 9016, Aotearoa New Zealand 13 *These authors contributed equally to this work 14 15 Abstract 16 From global nature conservation policies to carbon off-set private initiatives, the focus on tree promotion, and 17 tree planting in particular, as a nature-based solution to global environmental crises such as climatic change 18 and biodiversity loss dominates the current discourse. Yet, this fixation on trees does not reflect a scientific 19 consensus on the benefits of tree planting across diverse ecosystems and can have problematic implications 20 from both an ecological and socio-political perspective. In this paper, we synthesise cross-disciplinary insights 21 to challenge the common storyline of tree planting as a one-size-fits-all, nature-based solution to climate 22 change and biodiversity loss.