Chapter 4. Creationism Lite

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isthminia Panamensis, a New Fossil Inioid (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Chagres Formation of Panama and the Evolution of ‘River Dolphins’ in the Americas

Isthminia panamensis, a new fossil inioid (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Chagres Formation of Panama and the evolution of ‘river dolphins’ in the Americas Nicholas D. Pyenson1,2, Jorge Velez-Juarbe´ 3,4, Carolina S. Gutstein1,5, Holly Little1, Dioselina Vigil6 and Aaron O’Dea6 1 Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA 2 Departments of Mammalogy and Paleontology, Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, Seattle, WA, USA 3 Department of Mammalogy, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, USA 4 Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA 5 Comision´ de Patrimonio Natural, Consejo de Monumentos Nacionales, Santiago, Chile 6 Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Balboa, Republic of Panama ABSTRACT In contrast to dominant mode of ecological transition in the evolution of marine mammals, different lineages of toothed whales (Odontoceti) have repeatedly invaded freshwater ecosystems during the Cenozoic era. The so-called ‘river dolphins’ are now recognized as independent lineages that converged on similar morphological specializations (e.g., longirostry). In South America, the two endemic ‘river dolphin’ lineages form a clade (Inioidea), with closely related fossil inioids from marine rock units in the South Pacific and North Atlantic oceans. Here we describe a new genus and species of fossil inioid, Isthminia panamensis, gen. et sp. nov. from the late Miocene of Panama. The type and only known specimen consists of a partial skull, mandibles, isolated teeth, a right scapula, and carpal elements recovered from Submitted 27 April 2015 the Pina˜ Facies of the Chagres Formation, along the Caribbean coast of Panama. -

Origin and Beyond

EVOLUTION ORIGIN ANDBEYOND Gould, who alerted him to the fact the Galapagos finches ORIGIN AND BEYOND were distinct but closely related species. Darwin investigated ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE (1823–1913) the breeding and artificial selection of domesticated animals, and learned about species, time, and the fossil record from despite the inspiration and wealth of data he had gathered during his years aboard the Alfred Russel Wallace was a school teacher and naturalist who gave up teaching the anatomist Richard Owen, who had worked on many of to earn his living as a professional collector of exotic plants and animals from beagle, darwin took many years to formulate his theory and ready it for publication – Darwin’s vertebrate specimens and, in 1842, had “invented” the tropics. He collected extensively in South America, and from 1854 in the so long, in fact, that he was almost beaten to publication. nevertheless, when it dinosaurs as a separate category of reptiles. islands of the Malay archipelago. From these experiences, Wallace realized By 1842, Darwin’s evolutionary ideas were sufficiently emerged, darwin’s work had a profound effect. that species exist in variant advanced for him to produce a 35-page sketch and, by forms and that changes in 1844, a 250-page synthesis, a copy of which he sent in 1847 the environment could lead During a long life, Charles After his five-year round the world voyage, Darwin arrived Darwin saw himself largely as a geologist, and published to the botanist, Joseph Dalton Hooker. This trusted friend to the loss of any ill-adapted Darwin wrote numerous back at the family home in Shrewsbury on 5 October 1836. -

HOVASAURUS BOULEI, an AQUATIC EOSUCHIAN from the UPPER PERMIAN of MADAGASCAR by P.J

99 Palaeont. afr., 24 (1981) HOVASAURUS BOULEI, AN AQUATIC EOSUCHIAN FROM THE UPPER PERMIAN OF MADAGASCAR by P.J. Currie Provincial Museum ofAlberta, Edmonton, Alberta, T5N OM6, Canada ABSTRACT HovasauTUs is the most specialized of four known genera of tangasaurid eosuchians, and is the most common vertebrate recovered from the Lower Sakamena Formation (Upper Per mian, Dzulfia n Standard Stage) of Madagascar. The tail is more than double the snout-vent length, and would have been used as a powerful swimming appendage. Ribs are pachyostotic in large animals. The pectoral girdle is low, but massively developed ventrally. The front limb would have been used for swimming and for direction control when swimming. Copious amounts of pebbles were swallowed for ballast. The hind limbs would have been efficient for terrestrial locomotion at maturity. The presence of long growth series for Ho vasaurus and the more terrestrial tan~saurid ThadeosauTUs presents a unique opportunity to study differences in growth strategies in two closely related Permian genera. At birth, the limbs were relatively much shorter in Ho vasaurus, but because of differences in growth rates, the limbs of Thadeosau rus are relatively shorter at maturity. It is suggested that immature specimens of Ho vasauTUs spent most of their time in the water, whereas adults spent more time on land for mating, lay ing eggs and/or range dispersal. Specilizations in the vertebrae and carpus indicate close re lationship between Youngina and the tangasaurids, but eliminate tangasaurids from consider ation as ancestors of other aquatic eosuchians, archosaurs or sauropterygians. CONTENTS Page ABREVIATIONS . ..... ... ......... .......... ... ......... ..... ... ..... .. .... 101 INTRODUCTION . -

(Diapsida: Saurosphargidae), with Implications for the Morphological Diversity and Phylogeny of the Group

Geol. Mag.: page 1 of 21. c Cambridge University Press 2013 1 doi:10.1017/S001675681300023X A new species of Largocephalosaurus (Diapsida: Saurosphargidae), with implications for the morphological diversity and phylogeny of the group ∗ CHUN LI †, DA-YONG JIANG‡, LONG CHENG§, XIAO-CHUN WU†¶ & OLIVIER RIEPPEL ∗ Laboratory of Evolutionary Systematics of Vertebrates, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, PO Box 643, Beijing 100044, China ‡Department of Geology and Geological Museum, Peking University, Beijing 100871, PR China §Wuhan Institute of Geology and Mineral Resources, Wuhan, 430223, PR China ¶Canadian Museum of Nature, PO Box 3443, STN ‘D’, Ottawa, ON K1P 6P4, Canada Department of Geology, The Field Museum, 1400 S. Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605-2496, USA (Received 31 July 2012; accepted 25 February 2013) Abstract – Largocephalosaurus polycarpon Cheng et al. 2012a was erected after the study of the skull and some parts of a skeleton and considered to be an eosauropterygian. Here we describe a new species of the genus, Largocephalosaurus qianensis, based on three specimens. The new species provides many anatomical details which were described only briefly or not at all in the type species, and clearly indicates that Largocephalosaurus is a saurosphargid. It differs from the type species mainly in having three premaxillary teeth, a very short retroarticular process, a large pineal foramen, two sacral vertebrae, and elongated small granular osteoderms mixed with some large ones along the lateral most side of the body. With additional information from the new species, we revise the diagnosis and the phylogenetic relationships of Largocephalosaurus and clarify a set of diagnostic features for the Saurosphargidae Li et al. -

New Finds of Giant Raptorial Sperm Whale Teeth (Cetacea, Physeteroidea) from the Westerschelde Estuary (Province of Zeeland, the Netherlands)

1 Online Journal of the Natural History Museum Rotterdam, with contributions on zoology, paleontology and urban ecology deinsea.nl New finds of giant raptorial sperm whale teeth (Cetacea, Physeteroidea) from the Westerschelde Estuary (province of Zeeland, the Netherlands) Jelle W.F. Reumer 1,2, Titus H. Mens 1 & Klaas Post 2 1 Utrecht University, Faculty of Geosciences, P.O. Box 80115, 3508 TC Utrecht, the Netherlands 2 Natural History Museum Rotterdam, Westzeedijk 345 (Museumpark), 3015 AA Rotterdam, the Netherlands ABSTRACT Submitted 26 June 2017 Two large sperm whale teeth were found offshore from Breskens in the Westerschelde Accepted 28 July 2017 estuary. Comparison shows they share features with the teeth of the stem physteroid Published 23 August 2017 Zygophyseter, described from the Late Miocene of southern Italy. Both teeth are however significantly larger than the teeth of theZygophyseter type material, yet still somewhat Author for correspondence smaller than the teeth of the giant raptorial sperm whale Livyatan melvillei, and confirm the Jelle W.F. Reumer: presence of so far undescribed giant macroraptorial sperm whales in the Late Miocene of [email protected] The Netherlands. Editors of this paper Keywords Cetacea, Odontoceti, Westerschelde, Zygophyseter Bram W. Langeveld C.W. (Kees) Moeliker Cite this article Reumer, J.W.F., Mens, T.H. & Post, K. 2017 - New finds of giant raptorial sperm whale teeth (Cetacea, Physeteroidea) from the Westerschelde Estuary (province of Copyright Zeeland, the Netherlands) - Deinsea 17: 32 - 38 2017 Reumer, Mens & Post Distributed under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 DEINSEA online ISSN 2468-8983 INTRODUCTION presence of teeth in both maxilla and mandibula they are iden- Fossil Physeteroidea are not uncommon in Neogene marine tified as physeteroid teeth (Gol’din & Marareskul 2013). -

Exceptional Vertebrate Biotas from the Triassic of China, and the Expansion of Marine Ecosystems After the Permo-Triassic Mass Extinction

Earth-Science Reviews 125 (2013) 199–243 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Exceptional vertebrate biotas from the Triassic of China, and the expansion of marine ecosystems after the Permo-Triassic mass extinction Michael J. Benton a,⁎, Qiyue Zhang b, Shixue Hu b, Zhong-Qiang Chen c, Wen Wen b, Jun Liu b, Jinyuan Huang b, Changyong Zhou b, Tao Xie b, Jinnan Tong c, Brian Choo d a School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1RJ, UK b Chengdu Center of China Geological Survey, Chengdu 610081, China c State Key Laboratory of Biogeology and Environmental Geology, China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), Wuhan 430074, China d Key Laboratory of Evolutionary Systematics of Vertebrates, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China article info abstract Article history: The Triassic was a time of turmoil, as life recovered from the most devastating of all mass extinctions, the Received 11 February 2013 Permo-Triassic event 252 million years ago. The Triassic marine rock succession of southwest China provides Accepted 31 May 2013 unique documentation of the recovery of marine life through a series of well dated, exceptionally preserved Available online 20 June 2013 fossil assemblages in the Daye, Guanling, Zhuganpo, and Xiaowa formations. New work shows the richness of the faunas of fishes and reptiles, and that recovery of vertebrate faunas was delayed by harsh environmental Keywords: conditions and then occurred rapidly in the Anisian. The key faunas of fishes and reptiles come from a limited Triassic Recovery area in eastern Yunnan and western Guizhou provinces, and these may be dated relative to shared strati- Reptile graphic units, and their palaeoenvironments reconstructed. -

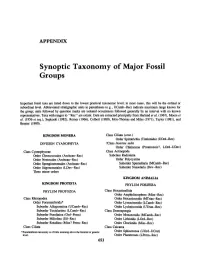

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida -

Mammalia: Cetacea) from the Chagres Formation of Panama and the Evolution of "River Dolphins" in the Americas

Reviewing Manuscript To avoid issues relating to nomenclatural acts, minor sections of this article which reported on the naming of a new species, and which did not make it into the final publication, have been redacted. a new fossil inioid (Mammalia: Cetacea) from the Chagres Formation of Panama and the evolution of "river dolphins" in the Americas Nicholas D Pyenson, Jorge Velez-Juarbe, Carolina S. Gutstein, Holly Little, Dioselina I Vigil, Aaron O'Dea In contrast to dominant mode of ecological transition in the evolution of marine mammals, different lineages of toothed whales (Odontoceti) have repeatedly invaded freshwater ecosystems during the Cenozoic era. The so-called “river dolphins” are now recognized as independent lineages that converged on similar morphological specializations (e.g., longirostry). In South America, the two endemic “river dolphin” lineages form a clade (Inioidea), with closely related fossil inioids from marine rock units in the South Pacific and North Atlantic Oceans. Here we describe a new species of fossil inioid, nov. gen., nov. sp., from the late Miocene of Panama. The type and only known specimen consists of a partial skull, mandibles, isolated teeth, and a right scapula recovered from the Piña facies of the Chagres Formation, along the Caribbean coast of Panama. Sedimentological and associated fauna from the Piña facies point to fully marine conditions with high planktonic productivity 6.8-7.5 million years ago (middle Messinian to earliest Tortonian), which predates final closure of the Isthmus of Panama. Along with ecomorphological data, we propose that was primarily a marine inhabitant, similar to modern oceanic delphinoids. -

New Discoveries of Fossil Toothed Whales from Peru: Our Changing Perspective of Beaked Whale and Sperm Whale Evolution

Quad. Mus. St. Nat. Livorno, 23: 13-27 (2011) DOI code: 10.4457/musmed.2010.23.13 13 New discoveries of fossil toothed whales from Peru: our changing perspective of beaked whale and sperm whale evolution OLIVIER LAMBERT1 SUMMARY: Following the preliminary description of a first fossil odontocete (toothed whale) from the Miocene of the Pisco Formation, southern coast of Peru, in 1944, many new taxa from Miocene and Pliocene levels of this formation were described during the 80’s and 90’s, (families Kentriodontidae, Odobenocetopsidae, Phocoenidae, and Pontoporiidae). Only one Pliocene Ziphiidae (beaked whale) and one late Miocene Kogiidae (dwarf sperm whale) were defined. Modern beaked whales and sperm whales (Physeteroidea = Kogiidae + Physeteridae) share several ecological features: most are predominantly teuthophagous, suction feeders, and deep divers. They further display a highly modified cranial and mandibular morphology, including tooth reduction in both groups, high vertex and sexually dimorphic mandibular tusks in ziphiids, and development of a vast supracranial basin in physeteroids. New discoveries from the Miocene of the Pisco Formation enrich the fossil record of ziphiids and physeteroids and shed light on various aspects of their evolution. From Cerro Colorado, a new species of the ziphiid Messapicetus lead to the description of features previously unknown in fossil members of the family: association of complete upper and lower tooth series with tusks, hypothetical sexual dimorphism in the development of the tusks, skull anatomy of a calf... A new small ziphiid from Cerro los Quesos, Nazcacetus urbinai, is characterized by the reduction of the dentition: a pair of apical mandibular tusks associated to vestigial postapical teeth, likely hold in the gum. -

1 PHILATELIC SUPPLIES (M.B.O'neill)

List up-dated Winter 2020 (10.12.20) P R E H I S T O R Y (1 9 6 5 - 2 0 2 0) SPECIAL OFFERS EDITION (includes Fossils and Prehistoric Animals) PHILATELIC SUPPLIES (M.B.O'Neill) 359 Norton Way South Letchworth Garden City HERTS ENGLAND SG6 1SZ Telephone 01462-684191 during office hours 9.15-3.15pm Mon.-Fri.) Web-site: www.philatelicsupplies.co.uk email: [email protected] TERMS OF BUSINESS: & Notes on these lists: (Please read before ordering). 1). All stamps are unmounted mint unless specified otherwise. Our prices are also in Sterling, (£). 2). Lists are updated about every 26 weeks to include most recent stock movements and New Issues; they are therefore reasonably accurate stockwise 100% pricewise. This reduces the need for "credit notes" and refunds. Alternatives may be listed in case some items are out of stock. However, these popular lists are still best used as soon as possible. Next Prehistory listings will be printed in 6 & 12 months time so please indicate when next we should send a list on your order form. 3). New Issues Services can be provided if you wish to keep your collection up to date on a Standing Order basis. Details of this service & forms can be sent on request. Regret we do not run an on approval service. 4).All orders on our order forms are attended to by return of post. We will keep a photocopy it and return your annotated original. 5). Other Thematic Lists are available on request; Minerals/Geology, Fauna, 6). -

Marine Vertebrate Assemblages in the Southwest Atlantic During the Miocene

Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2011, 103, 423–440. With 7 figures Marine vertebrate assemblages in the southwest Atlantic during the Miocene ALBERTO LUIS CIONE1,2*, MARIO ALBERTO COZZUOL3, MARÍA TERESA DOZO2,4 and CAROLINA ACOSTA HOSPITALECHE1,2 1División Palaeontología de Vertebrados, Museo de La Plata, Paseo del Bosque s/n, 1900 La Plata, Argentina 2Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Buenos Aires, Argentina. 3Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Avenue Antônio Carlos, 6627 – Pampulha, 31270-910, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil 4CENPAT – CONICET, 9120 Puerto Madryn, Argentina Received 10 March 2011; accepted for publication 10 March 2011bij_1685 423..440 Two biogeographical units are generally recognized in the present shelf area of Argentina: the Magellanian and Argentinian Provinces. The two provinces differ in their fossil record. The evolution of these provinces has been characterized by migrations, extinctions, pseudoextinctions and, perhaps, even speciation events. Marine verte- brate assemblages with some similarities to the Argentinian fauna were already present in the Miocene, whereas no associations similar to those of the Magellanian fauna have been found in South America before the Pleistocene. Two successive major marine transgressions flooded northern Patagonia during the Miocene: the ‘Patagoniense’ (Early Miocene) and the ‘Entrerriense’ (Middle to Late Miocene). We analyse three rich fossil assemblages that were formed during these transgressions. The absence of Magellanian Miocene vertebrate assemblages is consis- tent with the hypothesis of a more southern distribution of the cold-temperate fauna at that time. In Patagonia, as in other regions, an increased number of living groups appeared from the Lower to Upper Miocene. -

Bonebed of Lamerden (Germany) As Palaeoenvironment Indicators in the Germanic Basin

Open Geosci. 2015; 7:755–782 Research Article Open Access Cajus G. Diedrich * The vertebrates from the Lower Ladinian (Middle Triassic) bonebed of Lamerden (Germany) as palaeoenvironment indicators in the Germanic Basin DOI 10.1515/geo-2015-0062 sis; palaeoenvironment; palaeobiogeography; Germanic Basin; Central Europe Received January 28, 2013; accepted May 21, 2015 Abstract: A marine/limnic vertebrate fauna is described from the enodis/posseckeri Bonebed mixed in a bivalve shell-rich bioclastic carbonate rudstone at the eastern 1 Introduction coastal margin of the Rhenish Massif mainland at Lamer- den (Germany) within the western Germanic Basin (Cen- Middle Triassic vertebrate skeleton or bone localities and tral Europe). The condensation layer is of Fassanian (La- bonebed layers are known from all over the “Pangaean dinian, Middle Triassic) in age. The vertebrate biodiver- Globe”, especially Northern America, Europe, and China sity includes ve dierent shark, and several actinoptery- (Figure 1A) [e.g. [1–7]]. In north-western Germany, a higher gian sh species represented by teeth and scales. Abun- density of vertebrate sites (Figure 1B) is the result of dant isolated bones from a small- and a large-sized pachy- many active limestone quarries which expose bonebeds th pleurosaur Neusticosaurus species, which can be com- within dierent layers since the 19 century. The old- posed as incomplete skeletons, originate from dense pop- est described historical sites are in southern Germany ulations of dierent individual age stages. Important fa- near Bayreuth (Bavaria) and became famous with the cies indicator reptiles are from the thalattosaur Blezin- world-wide rst sauropterygian monograph published by geria ichthyospondyla which postcranial skeleton is re- Hermann von Meyer [8].