African American History at Colonial Williamsburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Membership Program Offers Value and Supports the Growing Art

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation P.O. Box 1776 Williamsburg, Va. 23187-1776 www.colonialwilliamsburg.com New Membership Program Offers Value and Supports the Growing Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg Individual and family memberships offer value and benefits and support the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum “Dude,” tobacconist figure ca. 1880, museum purchase, Winthrop Rockefeller, part of the exhibition “Sidewalks to Rooftops: Outdoor Folk Art” at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum; rendering of the South Nassau Street entrance to the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg; “Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I”, artist unidentified, 1590-1600, gift of Preston Davie, part of the exhibition “British Masterworks: Ninety Years of Collecting at Colonial Williamsburg,” opening Feb. 15 at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum. WILLIAMSBURG, Va. (Feb. 5, 2019) –Colonial Williamsburg offers a new opportunity to enjoy and support its world-class art museums, the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, with annual individual and family memberships that provide guest benefits and advance both institutions’ exhibition and interpretation of America’s shared history. The DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, which showcases the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670-1840, and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, home to the nation’s premier collection of American folk art, remain open during their donor-funded, $41.7-million expansion, which broke ground in 2017 and is scheduled for completion this year. Once completed, the expansion will add 65,000 square feet with a 22- percent increase in exhibition space as well as a new visitor-friendly entrance on Nassau Street. -

Natioflb! HISTORIC LANDMARKS Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR ^^TAT"E (Rev

THEME: ^fch:chitecture NATIOflB! HISTORIC LANDMARKS Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ^^TAT"E (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE VirjVirginia COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES James City AT; °;-' T; J"" Bil$VENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) COMMON: Carter's Grove Plantation AND/OR HISTORIC: Carter's Grove Plantation STREET AND NUMBER: Route 60, James City County CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: vicinity of Williamsburg 001 COUNTY: Virginia 51 James City 095 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District gg Building d Public Public Acquisition: K Occupied Yes: i iii . j I I Restricted Site Q Structure 18 Private || In Process LJ Unoccupied ' ' i i r> . i 6*k Unrestricted D Object D Both | | Being 'Considered D Preservation work lc* in progress ' 1 PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) 53 Agricultural [ | Government | | Park Transportation S Comments [~| Commercial I I Industrial |X[ Private Residence Q Other ....___.,, The _____________kitchen D Educotionai D Military rj Religious dependency is occupied by Mr. & D Entertainment D Museum rj Scientific Mrs. McGinley. The rest of the ' WiK«-¥.:.:jliBi.; ;ttjr: the" pub^li;^! OWNER'S NAME: Colonial Williamsburg, Inc., Carlisle H. Humelsine, President Virginia STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: CODF Williamsburg Virginia 51 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC: Clerk of the Circuit Court P.O. Box 385 CityJames STREET AND NUMBER: Court Street (2 blocks south of -

Regional Map

REGIONAL MAP N e w K e n t G ll o u c e s t e r ñðò11 James City County, Williamsburg, York County York Chesapeake River Bay ¤£17 (!30 (!30 15 ñðò 5 n CAMP PEARY Æc 4 2 R ! O CHA MBE AU D R 64 RD ND § O ¨¦ M ICH R Y K P E 60 IN S D L 60 R ¤£ E D M ON U ¤£ H M ICH R 25 199 5 1 8 E R 5 ! OCH (! AM B ^ n EAU ^ DR CHEATHAM 3 ñðò 31 3 "11 n ANNEX 4 ^ 2^ " ^ USCG 9 ST " LLARD ñ 3 BA TRAINING C 6 O 3 O ! K CENTER 19 R ^ D YORKTOWN 64 ñðò 2 ¨¦§ v® 17 2 17 ¤£ GOO 15 SLEY RD 173 ñðò n !n6 (! G 238 E O 3 R (! G 19 E ¹º W RIC A H S G n M O H O ND I O R N D D G W 143 CHEATHAM T O IN 3 N ! M N ( E ANNEX EM C O K n R R YORKTOWN IA D 6 L H NAVAL ñðò WY D 21 WEAPONS R G 610 R ñðò U n 14 9 STATION B Æc 1 (! S M 1 Poquoson C A 132 A I 11 River 614 P L " ñðò I n L ! T I ( O W ñðò (! L L D A L 14 2 N 10 2 O 3 D " 4 1 " I N 16 E Y G n T K ^ R P U 64 J a m e s D O J a m e s R 17 7 R ñðò ¨¦§ E T ¤£ N 5 E " ñðò C ii t y C H U S 10 M 8 I EL U ! S Q IN 30 E R P n A 620 K 8 W M " Y Y P o q u o s o n K (! P o q u o s o n W n P n SEC E ON D ST N P I A S R 60 G L IC E 4 E n H M M RD S ! U £ T O S ¤ H 13 S 24 ND PA 1 R BY 16 27 D R E ñðò ^ Æc ñðò A n M Y ñðò n n P 199 5 W YO G K R ! E ñðò K S O T P 1 (! 64 R M " 105 G E ER E N R 13 I IM ¨¦§ W A S (! A C S L 1 TR H E v® L IN PO 173 M C n G N AHO T U N D TAS V O H H 6 23 TRL L (! N 12 E B M 17 6 N 9 E ! R IS " " M 171 Y T O n S R S ñðò E Æc U IA T (! ñðò E L V A T H R W O O Y W L F Y L 7 D 2 E V T ! L H C 3 I B E 29 T 14 C N H 2 1 G n R O ñ M I ER E M RI B ^ MAC E TR N n ¹º L E K D R 60 64 D 1 ¤£ 7 2 1 26 ×× ¨¦§ D LV -

Colonial Williamsburg to Resume Limited Onsite Programming June 14

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation P.O. Box 1776 Williamsburg, Va. 23187-1776 colonialwilliamsburg.org Colonial Williamsburg to Resume Limited Onsite Programming June 14 Select sites to reopen at reduced capacity, changes to guest experience; face coverings and social distancing required for staff and guests inside foundation-owned buildings Colonial Williamsburg will resume limited public programming at select sites on June 14. This first wave of openings is based on Virginia’s move into Phase 2 of the state’s Forward Virginia initiative. The foundation will open additional sites and expand programming in coming weeks and months pending government and public health guidance to further limit health risks associated with COVID-19. “We are eager to welcome employees and guests back to Colonial Williamsburg, but re- opening our public sites requires that we work together so that we all remain safe,” said President and CEO Cliff Fleet. “Our phased re-opening plan is based on state guidelines and is fully supported by our regional partners. With this plan in place, we can move at a measured pace toward our shared goal of a return to normal operations.” The following Colonial Williamsburg indoor and open-air sites will operate at reduced capacity and follow site-specific safety guidelines developed as part of the foundation’s COVID-19 business resumption plan, which is consistent with the state’s Phase 2 requirements: • The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg • Governor’s Palace • Capitol • Courthouse • Weaver trade shop • Carpenter’s Yard • Peyton Randolph Yard • Colonial Garden • Magazine Yard • Armoury Yard • Brickyard • George Wythe Yard • Custis Square, including tours The Williamsburg Lodge is currently open with additional hospitality operations expanding based on sustainable business demand. -

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: RACE, RELIGION, and CLASS: THE

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: RACE, RELIGION, AND CLASS: THE THOUGHT OF REVEREND GEORGE FREEMAN BRAGG, JR., Stanley Jenkins Jr., Master of Arts, March 2019 Thesis Chair: Debra N. Ham, Ph.D. Department of History George Freeman Bragg (1863-1940) was a black Episcopal priest and civil rights activist during the Progressive Era in America. He was also a brilliant yet complicated man whose thoughts and opinions were in tension with one another. Bragg’s writings are not one dimensional and lend themselves to various interpretations. Hence, it is possible to view him as either an accommodationist, a man imbued with a racial consciousness or an unwieldy blend of both. However, much of the available literature on Bragg presents a one-dimensional portrait of him. Celebrating his many civil rights struggles, these portraits ignore the sometimes contradictory and complex nature of his thought. Indeed, Bragg bears witness to historian Wilson J. Moses’s contention that all serious prolonged thinking eventually results in contradiction. Hence, the following thesis will critically examine the writings of Bragg in an effort to flesh out the complex character of his thought. It will also attempt to provide a workable explanation to explain the same. The writings of Bragg were not the only sources used to examine his thought. The works of historians Wilson J. Moses, Kevin K. Gaines, and Evelyn Higginbotham that focused on black elites, racial uplift ideology, and classism were indispensable to this study. Notwithstanding, there were a plethora of primary and secondary sources that undergirded this study and helped to socially contextualize and interrogate Bragg’s complex thought. -

NOMINATION FORM for NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER Dal"E

_, i.. t, 'I . •I · Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF fHE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NA Tl ON Al PARK SERVICE Virginia COUNTY, NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES James City INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DAl"E COMMON: George Wythe House ANOI OR HISTORIC, Wythe House ,__ -·-· -·-:-",-,_:,v.•.,'.•.'c:'. •i•:?-,•· \/:c+i,)"!;)'.(' :{/(;".;.\p; LC '<it\:\ STREET ANo NUMBER: On the west side of the Palace Green between the Duke of Gloucester Street and Prince George Street. --CITY -OR-------------------------------------------------1 TOWN: Williamsburg STATE COOE COUNTY · CODE Virginia •--·-:•, .,. .. __ . 1):\;¢tAs~iFiC:.Xi'tqif :_/</ >:Y /- :· T'•• .. _.L: <> , <f %%\Xfr ;?\ '" _.,..,. ., ....., .___ _ : -:-: : .•:-. ··:::-:;:.':• .;;(:;}'.)\:;:.~:y CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC z D District rn Bui /ding D Public I Public Acquisitil>n: n Occupiod Yes; 0 Restricted D Sile 0 Structu,e rn PriYate 0 In Process 0 Unoccupied D Both 0 Beir,g Con~id&red Unrestricted 0 Object 0 0 Pr&s&rvation work \ ixJ 1- in progr&ss \ D No u PRESENT USE (CJ>eck on~ or More BS Appropr/eto) D Agricultura l D Government 0 Pork 0 Trol'\sportatl on 0 Comm&nts 0 Commercial 0 Industrial 0 Pr/vote Residenco 0 Other ($pt,c/!y) D Educational D M;J itary 0 R&ligiou• D Entorta i rimenf ~ Museum 0 Scientific OWNEA' s NAME: -I"' ), Colonial Williamsburg, Inc., Division of Interpretation -I "1 w Sl"AEET AND NUMBER: UJ Goodwin Building CITY OR TOWN : STATE< CODE Willi4msburg 23185 Virginia ~~~l~'OF'.t{fi~Wtl'.]~~p'rtl&:i'.:L9~/ --._. -

WILLIAMSBURG GARDEN CLUB Williamsburg 93

HOSTED BY THE WILLIAMSBURG GARDEN CLUB Williamsburg 93 TICKET PRICE INCLUDES ADMISSION TO THE FOLLOWING 6 SITES: Benjamin Powell Garden tavern, lodging house, store and gunsmith’s 109 North Waller Street shop. The simple but quaint garden plan consists of curved geometric beds over- The small pleasure garden between the flowing with a variety of plants that change house and the office has a brick path that color with the seasons. An ornamental crisscrosses four parterres planted with summerhouse features a basket-weave ferns and small bulbs. The vertical scale brick pattern. The property is surrounded of the garden is attained with flowering by a yaupon hedge. dogwoods and ancient crepe myrtles. Large, shoulder-high oakleaf hydrangeas encircle Palmer House and Garden the gardens. A kitchen garden is posi- 420 East Duke of Gloucester Street tioned behind the pleasure garden and features period vegetables and herbs in an One of Colonial Williamsburg’s 88 origi- early version of “companion planting.” nal 18th century buildings, this two-story brick home was built by John Palmer, a Christiana Campbell’s Tavern lawyer and bursar at William & Mary, after a smaller home on the property burned Photos courtesy of Laura Viancour and Colonial Williamsburg Garden, 101 South Waller Street down in 1754. The house was substantially Mrs. Campbell acquired the property in enlarged during the Civil War and was oc- 1774, and it has provided welcoming ac- cupied as headquarters by both General commodations for dining as well as lodg- Joseph Johnston of the Confederate Army ing for two and a half centuries. -

Black History Month 2019: Special Exhibition; Featured Programs Mark 40 Years of African-American Interpretation

Black History Month 2019: Special Exhibition; Featured Programs Mark 40 Years of African-American Interpretation WILLIAMSBURG, Va. (Jan. 21, 2019) – This February Colonial Williamsburg celebrates Black History Month by showcasing the best of its year-round African-American programming, including the new “Music was my Refuge,” as well as tours and the grand opening Feb. 18 of a special exhibition at the Raleigh Tavern: “Revealing the Priceless: 40 Years of African-American Interpretation.” The exhibition in the Raleigh’s Daphne and Billiards rooms memorializes by name each of the African-American men and women known to have lived in the city during the period Colonial Williamsburg interprets, from 1763 to 1785. It also examines the contributions of hundreds of interpreters, administrators, historians, archeologists, curators and community partners who have contributed to telling the story of over half of the city’s 18th-century population. “So often our shared American story is told with brief reference to nameless ‘slaves.’ Early African Virginians were, first and foremost, people like us with lives, loves, hopes and struggles, as nearly all lived in legal bondage while others in society demanded unalienable rights,” said Actor-interpreter Stephen Seals, program manager for the 40th anniversary commemoration. “Our goal is to share their enduring stories. In February and throughout 2019 we invite guests to experience our remarkable new exhibition honoring them and those who tell their stories, along with the powerful interpretive programming we present every day.” Black History Month programming highlights include the new “Music was my Refuge,” an uplifting journey from the 18th century to today, presented at 3 p.m. -

Learning from Yesterday . . . TODAY: a Day Trip

Learning from Yesterday . TODAY A Day Trip into History Department of Education Outreach Department of School and Youth Group Tours 2 INTRODUCTION A class field trip should be more than a day away from the classroom! It is an opportunity for an educational experience that complements the regular course of study, and it is imperative that teachers plan and implement activities that create worthwhile learning experiences for their students. The best way to accomplish this goal is to adopt a three-part strategy: careful preparation beforehand; meaningful exercises to engage students while at the site; and a thorough debriefing after returning to the classroom. This guide is designed to assist teachers who are planning a field trip to, but may lack background knowledge or familiarity with, Colonial Williamsburg. It is also meant to suggest new approaches for educators who have made a visit to Colonial Williamsburg part of their students’ instruction for many years. There are more ideas than can be used for a single trip, but all are provided so teachers can select those that best meet their instructional objectives and student needs. In addition to specific sample lessons, extra material has been provided at the end of each section that can be further developed into lessons. Some lessons overlap in subject matter, but offer alternative strategies or target different skills. Each lesson can be adjusted according to grade level and the time available to the teacher. This guide is intended to make a trip to Colonial Williamsburg a more enjoyable and worthwhile learning venture for all involved. Section 1: BEFORE THE VISIT – Set the Stage for Learning Sample Lessons and Additional Lesson/Activity Suggestions Teachers set forth the objectives for the visit and provide opportunities to gather needed background information for students to understand the purpose of the field trip. -

Chapter 9 - Institutions

Chapter 9 - Institutions INSTITUTIONS Since its establishment in 1699, Williamsburg has been defined by its major public institutions. William & Mary and Bruton Parish Church preceded the city and were its first institutional partners. Virginia’s colonial government was based here from Williamsburg’s founding in 1699 until the capital was moved to Richmond in 1780. The Publick Hospital, which became Eastern State Hospital, was a significant presence in the city from 1773 until completing its move to James City County in 1970. Finally, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation traces its origin to 1926, when John D. Rockefeller, Jr. began the Colonial Capital restoration. William & Mary and Colonial Williamsburg comprise 43% of the city’s total land area. This chapter will discuss the impact of these two institutions on the city. 2021 Comprehensive Plan Chapter 9 - Institutions Page 9-1 Chapter 9 - Institutions WILLIAM & MARY William & Mary, one of the nation’s premier state-assisted liberal arts universities, has played an integral role in the city from the start. The university was chartered in 1693 by King William III and Queen Mary II and is the second oldest higher educational institution in the country. William & Mary’s total enrollment in the fall of 2018 was 8,817 students, 6,377 undergraduate, 1,830 undergraduate, and 610 first-professional students. The university provides high-quality undergraduate, graduate, and professional education comprised of the Schools of Arts and Sciences, Business Administration, Education, Law, and Marine Science. The university had 713 full-time faculty members and 182 part-time faculty members in 2018/19. The university’s centerpiece is the Wren Building, attributed apocryphally to the English architect Sir Christopher Wren. -

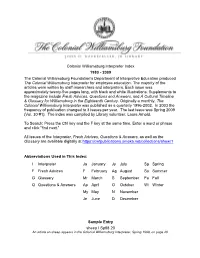

Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter Index 1980

Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter Index 1980 - 2009 The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Department of Interpretive Education produced The Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter for employee education. The majority of the articles were written by staff researchers and interpreters. Each issue was approximately twenty-five pages long, with black and white illustrations. Supplements to the magazine include Fresh Advices, Questions and Answers, and A Cultural Timeline & Glossary for Williamsburg in the Eighteenth Century. Originally a monthly, The Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter was published as a quarterly 1996-2002. In 2003 the frequency of publication changed to 3 issues per year. The last issue was Spring 2009 (Vol. 30 #1). The index was compiled by Library volunteer, Laura Arnold. To Search: Press the Ctrl key and the F key at the same time. Enter a word or phrase and click "find next.” All issues of the Interpreter, Fresh Advices, Questions & Answers, as well as the Glossary are available digitally at https://cwfpublications.omeka.net/collections/show/1 Abbreviations Used in This Index: I Interpreter Ja January Jy July Sp Spring F Fresh Advices F February Ag August Su Summer G Glossary Mr March S September Fa Fall Q Questions & Answers Ap April O October Wi Winter My May N November Je June D December Sample Entry sheep I Sp98 20 An article on sheep appears in the Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter, Spring 1998, on page 20. A abolition of slavery I Sp99 20-22, I Wi99/00 19-25, “Abuse of History: Selections from Dave Barry Slept Here, -

Slavery on Exhibition: Display Practices in Selected Modern American Museums

Slavery on Exhibition: Display Practices in Selected Modern American Museums by Kym Snyder Rice B.A. in Art History, May 1974, Sophie Newcomb College of Tulane University M.A. in American Studies, May 1979, University of Hawaii-Manoa A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2015 Dissertation directed by Teresa Anne Murphy Associate Professor of American Studies The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University Certifies that Kym Snyder Rice has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of November 22, 2014. This is the final approved form of the dissertation. Slavery on Exhibition: Display Practices in Selected Modern American Museums Kym Snyder Rice Dissertation Research Committee: Teresa Anne Murphy, Associate Professor of American Studies, Dissertation Director Barney Mergen, Professor Emeritus of American Studies, Committee Member Nancy Davis, Professorial Lecturer of American Studies, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2015 by Kym Snyder Rice All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements This dissertation has taken many years to complete and I have accrued many debts. I remain very grateful for the ongoing support of all my friends, family, Museum Studies Program staff, faculty, and students. Thanks to each of you for your encouragement and time, especially during the last year. Many people contributed directly to my work with their suggestions, materials, and documents. Special thanks to Fath Davis Ruffins and Elizabeth Chew for their generosity, although they undoubtedly will not agree with all my conclusions.