Design and Deception at Colonial Williamsburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Lafayette in Williamsburg” (Walking Tour)

Other Sites to Visit • African American Religion exhibit– Explore the religious heritage of Africans and their Virginia descendants. Lafayette in • American Indian Interpretation– Explore the diverse cultures of Native peoples striving to preserve their traditional way of life and learn about the roles they played in creating a new country. Williamsburg • Apothecary – Learn how medicine, wellness, and surgical practices of the 18th century compare to today. • Cabinetmaker & Harpsichord Maker – Watch expert woodworkers fashion the intricate details of luxury products with period hand tools. AMERICAN FRIENDS OF LAFAYETTE • Capitol – Take a guided tour of the first floor entering through the Courtroom and exiting through the House of Burgesses. Annual Meeting 2021 June 13, 2021 • Carpenter’s Yard – Discover how the carpenters use hand tools to transform trees into lumber and lumber into buildings. • Courthouse – Experience justice in the 18th century in an original building. • Gunsmith – See how rifles, pistols, and fowling pieces are made using the tools and techniques of the 18th-century. • Joinery – Watch our experts use saws, planes, hammers, and other tools to fashion wood into the pieces of a future building. • Milliner & Mantua-maker – Shop for latest hats, headwear, ornaments, and accessories. Watch as old gowns are updated to the newest 18th-century fashion. • Tailor – Touch and feel the many different sorts of fabrics and garments that clothed colonial Americans, from elegant suits in the latest London styles to the sturdy uniforms of Revolutionary soldiers. • Public Leather Works – Discover how workman cut, mold, and stitch leather and heavy textiles. • Printing Office & Bindery – Watch and learn as printers set type and use reproduction printing presses to manufacture colonial newspapers, political notices, pamphlets, and books. -

Williamsburg Reserve Collection Celebrating the Orgin of American Style

“So that the future may learn from the past.” — John d. rockefeller, Jr. 108 williamsburg reserve collection Celebrating the Orgin of American Style. 131109 colonial williamsburg Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg, the capital of the colony of Virginia, owed its inception to politics, its design to human ingenuity, and its prosperity to government, commerce and war. Though never larger in size than a small English country town, Virginia’s metropolis became Virginia’s center of imperial rule, transatlantic trade, enlightened ideas and genteel fashion. Williamsburg served the populace of the surrounding colonies as a marketplace for goods and services, as a legal, administrative and religious center, and as a resort for shopping,information and diversion. But the capital was also a complex urban community with its own patterns of work, family life and cultural activities. Within Williamsburg’s year round populations, a rich tapestry of personal, familial, work, social, racial, gender and cultural relationships could be found. In Williamsburg patriots such as Patrick Henry protested parliamentary taxation by asserting their right as freeborn Englishmen to be taxed only by representatives of their own choosing. When British authorities reasserted their parliamentary sovereign right to tax the King’s subjects wherever they reside, Thomas Jefferson, George Mason, James Madison, George Washington and other Virginians claimed their right to govern themselves by virtue of their honesty and the logic of common sense. Many other Americans joined these Virginians in defending their countrymen’s liberties against what they came to regard as British tyranny. They fought for and won their independence. And they then fashioned governments and institutions of self-rule, many of which guide our lives today. -

New Membership Program Offers Value and Supports the Growing Art

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation P.O. Box 1776 Williamsburg, Va. 23187-1776 www.colonialwilliamsburg.com New Membership Program Offers Value and Supports the Growing Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg Individual and family memberships offer value and benefits and support the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum “Dude,” tobacconist figure ca. 1880, museum purchase, Winthrop Rockefeller, part of the exhibition “Sidewalks to Rooftops: Outdoor Folk Art” at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum; rendering of the South Nassau Street entrance to the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg; “Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I”, artist unidentified, 1590-1600, gift of Preston Davie, part of the exhibition “British Masterworks: Ninety Years of Collecting at Colonial Williamsburg,” opening Feb. 15 at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum. WILLIAMSBURG, Va. (Feb. 5, 2019) –Colonial Williamsburg offers a new opportunity to enjoy and support its world-class art museums, the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, with annual individual and family memberships that provide guest benefits and advance both institutions’ exhibition and interpretation of America’s shared history. The DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, which showcases the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670-1840, and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, home to the nation’s premier collection of American folk art, remain open during their donor-funded, $41.7-million expansion, which broke ground in 2017 and is scheduled for completion this year. Once completed, the expansion will add 65,000 square feet with a 22- percent increase in exhibition space as well as a new visitor-friendly entrance on Nassau Street. -

Fall 2020 Newsletter Vol. 3, No. 2

FALL 2020 NEWSLETTER VOL. 3, NO. 2 ARCHIVES AND RECORDS DEPARTMENT CELEBRATES 75 YEARS Lester Cappon, the first director of Colonial Williamsburg's Department of Archives and Records, December 13, 1951. John Radditz, photographer. IN THIS ISSUE In November, the Colonial Williamsburg Department of Archives and Records celebrated the 75th anniversary of its founding. In Archives and Records Department the late 1930s, Colonial Williamsburg President Kenneth Chorley Celebrates 75: p. 1-4 initiated the first steps in creating an archives of the Restoration Aerial Perspectives on Wartime Williamsburg: p.- 5 9 when he requested that engineering firm Todd & Brown, land- James Craig Letter: p. 10 scape architect Arthur Shurcliff, and architectural firm Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn turn over their Restoration records. In 1939 Tracey Gulden Awarded Gonzales Grant: p. 11 Chorley observed, “The more I see of Williamsburg the more I am Digital Corner: p. 11-14 impressed with its permanence and the more I realize that many, 1 ARCHIVES AND RECORDS DEPARTMENT CELEBRATES 75 YEARS (continued) Archives and Records collection storage area in the basement of the Goodwin Office Building, 1948. Thomas L. Williams, photographer. many generations after we are all gone it is going to continue to have its effect on this country. Also, the more I see of it the more I am impressed with the value of preserving the archives of the Restoration … Therefore, I am very anxious to begin to build up permanent archives for the restoration.” A consultant from the National Archives conducted a survey of Restoration records in 1940 and proposed the establishment of a formal archives. -

Taverns in Tidewater Virginia, 1700-1774

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1968 Taverns in Tidewater Virginia, 1700-1774 Patricia Ann Gibbs College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Gibbs, Patricia Ann, "Taverns in Tidewater Virginia, 1700-1774" (1968). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624651. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-7t92-8133 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TAVERNS XH TIDEWATER VIRGINIA, 1700-1774 t 4 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requiremenfcs for the degree of Master of Arts By Patricia Ann Gibbs 1968 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, May 1968 Jane Carson, Ph.D. LlAftrJ ty. r ___ Edward M. Riley, Ph/b Thad W. Tate, Ph.D. 11 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to express appreciation to Dr* Jane Carson for her guidance, criticism, and en couragement in directing this thesis and to Dr* Edward M* Riley and Dr* Thad W. Tate# Jr*# for their careful reading and criticism of the manuscript* The writer thanks Colonial Williamsburg# Inc.# for the use of its research facilities and the staff of the Research Department for many helpful suggestions* iii TASI£ OF CONTENTS juatraxxB^n ....... -

Natioflb! HISTORIC LANDMARKS Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR ^^TAT"E (Rev

THEME: ^fch:chitecture NATIOflB! HISTORIC LANDMARKS Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ^^TAT"E (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE VirjVirginia COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES James City AT; °;-' T; J"" Bil$VENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) COMMON: Carter's Grove Plantation AND/OR HISTORIC: Carter's Grove Plantation STREET AND NUMBER: Route 60, James City County CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: vicinity of Williamsburg 001 COUNTY: Virginia 51 James City 095 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District gg Building d Public Public Acquisition: K Occupied Yes: i iii . j I I Restricted Site Q Structure 18 Private || In Process LJ Unoccupied ' ' i i r> . i 6*k Unrestricted D Object D Both | | Being 'Considered D Preservation work lc* in progress ' 1 PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) 53 Agricultural [ | Government | | Park Transportation S Comments [~| Commercial I I Industrial |X[ Private Residence Q Other ....___.,, The _____________kitchen D Educotionai D Military rj Religious dependency is occupied by Mr. & D Entertainment D Museum rj Scientific Mrs. McGinley. The rest of the ' WiK«-¥.:.:jliBi.; ;ttjr: the" pub^li;^! OWNER'S NAME: Colonial Williamsburg, Inc., Carlisle H. Humelsine, President Virginia STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: CODF Williamsburg Virginia 51 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC: Clerk of the Circuit Court P.O. Box 385 CityJames STREET AND NUMBER: Court Street (2 blocks south of -

1 2 3 4 5 a Brief Guide to Bruton Parish Church

A BRIEF GUIDE TO BRUTON PARISH CHURCH (1) THE TOWER: The Tower was added to the church in 1769 and 1 houses the historic Tarpley Bell, given to Bruton Parish in 1761. It continues to summon worshippers every day. Inside the doorway of the Tower is a bronze bust of the Reverend W.A.R. Goodwin, rector, 1903-1909 and 1926-1938. (2) THE WEST GALLERY: Erected for The College of William and Mary students and the only original part of the interior, this gallery has a handrail with visible initials carved nearly 300 years ago. (3) THE HIGH BOX PEWS: These pews with doors were typical of unheated eighteenth-century English churches. Names on the doors 2 commemorate parish leaders and well-known patriots who worshipped here as college students or members of the colonial General Assembly. Names such as Patrick Henry, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe and John Marshall remind us of the important place of Bruton Parish in colonial and early U.S. history. (4) THE GOVERNOR’S PEW: Reserved for the royal governor and Council members, 3 this pew has an ornate canopied chair. In colonial days it had curtains for privacy and warmth. Church wardens and vestrymen occupied the pews nearer the altar. Today, the choir uses them. (5) THE BRONZE LECTERN: In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt presented the lectern to Bruton to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the first permanent English settlement and the establishment of the Anglican church at Jamestown. Near the lectern are the 4 gravestones of royal Governor Francis Fauquier and patriot Edmund Pendleton. -

Privacy, Exclusivity, and Food Complexity in Colonial Taverns

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2015 Inviting the Principle Gentlemen of the City: Privacy, Exclusivity, and Food Complexity in Colonial Taverns Lauren Elizabeth Gryctko College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Gryctko, Lauren Elizabeth, "Inviting the Principle Gentlemen of the City: Privacy, Exclusivity, and Food Complexity in Colonial Taverns" (2015). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626788. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-672j-9m59 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Inviting the Principle Gentlemen of the City: Privacy, Exclusivity, and Food Complexity in Colonial Taverns Lauren Elizabeth Gryctko Madison Heights, Virginia Bachelors of Science, James Madison University, 2011 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology The College of William and Mary May, 2015 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts o ^ ( x x i / u x ^ Lauren Elizabetl/Gryctko Approved by the Committee, April, 2015 C c <vv < / v ___ Committee Chair Professor Kathleen Bragdon, Anthropology The College of William & Mary Professor Joanne Bowen, Anthropology The College of William & Mary Associate ProfessorIs Frederick H. -

Regional Map

REGIONAL MAP N e w K e n t G ll o u c e s t e r ñðò11 James City County, Williamsburg, York County York Chesapeake River Bay ¤£17 (!30 (!30 15 ñðò 5 n CAMP PEARY Æc 4 2 R ! O CHA MBE AU D R 64 RD ND § O ¨¦ M ICH R Y K P E 60 IN S D L 60 R ¤£ E D M ON U ¤£ H M ICH R 25 199 5 1 8 E R 5 ! OCH (! AM B ^ n EAU ^ DR CHEATHAM 3 ñðò 31 3 "11 n ANNEX 4 ^ 2^ " ^ USCG 9 ST " LLARD ñ 3 BA TRAINING C 6 O 3 O ! K CENTER 19 R ^ D YORKTOWN 64 ñðò 2 ¨¦§ v® 17 2 17 ¤£ GOO 15 SLEY RD 173 ñðò n !n6 (! G 238 E O 3 R (! G 19 E ¹º W RIC A H S G n M O H O ND I O R N D D G W 143 CHEATHAM T O IN 3 N ! M N ( E ANNEX EM C O K n R R YORKTOWN IA D 6 L H NAVAL ñðò WY D 21 WEAPONS R G 610 R ñðò U n 14 9 STATION B Æc 1 (! S M 1 Poquoson C A 132 A I 11 River 614 P L " ñðò I n L ! T I ( O W ñðò (! L L D A L 14 2 N 10 2 O 3 D " 4 1 " I N 16 E Y G n T K ^ R P U 64 J a m e s D O J a m e s R 17 7 R ñðò ¨¦§ E T ¤£ N 5 E " ñðò C ii t y C H U S 10 M 8 I EL U ! S Q IN 30 E R P n A 620 K 8 W M " Y Y P o q u o s o n K (! P o q u o s o n W n P n SEC E ON D ST N P I A S R 60 G L IC E 4 E n H M M RD S ! U £ T O S ¤ H 13 S 24 ND PA 1 R BY 16 27 D R E ñðò ^ Æc ñðò A n M Y ñðò n n P 199 5 W YO G K R ! E ñðò K S O T P 1 (! 64 R M " 105 G E ER E N R 13 I IM ¨¦§ W A S (! A C S L 1 TR H E v® L IN PO 173 M C n G N AHO T U N D TAS V O H H 6 23 TRL L (! N 12 E B M 17 6 N 9 E ! R IS " " M 171 Y T O n S R S ñðò E Æc U IA T (! ñðò E L V A T H R W O O Y W L F Y L 7 D 2 E V T ! L H C 3 I B E 29 T 14 C N H 2 1 G n R O ñ M I ER E M RI B ^ MAC E TR N n ¹º L E K D R 60 64 D 1 ¤£ 7 2 1 26 ×× ¨¦§ D LV -

Colonial Williamsburg to Resume Limited Onsite Programming June 14

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation P.O. Box 1776 Williamsburg, Va. 23187-1776 colonialwilliamsburg.org Colonial Williamsburg to Resume Limited Onsite Programming June 14 Select sites to reopen at reduced capacity, changes to guest experience; face coverings and social distancing required for staff and guests inside foundation-owned buildings Colonial Williamsburg will resume limited public programming at select sites on June 14. This first wave of openings is based on Virginia’s move into Phase 2 of the state’s Forward Virginia initiative. The foundation will open additional sites and expand programming in coming weeks and months pending government and public health guidance to further limit health risks associated with COVID-19. “We are eager to welcome employees and guests back to Colonial Williamsburg, but re- opening our public sites requires that we work together so that we all remain safe,” said President and CEO Cliff Fleet. “Our phased re-opening plan is based on state guidelines and is fully supported by our regional partners. With this plan in place, we can move at a measured pace toward our shared goal of a return to normal operations.” The following Colonial Williamsburg indoor and open-air sites will operate at reduced capacity and follow site-specific safety guidelines developed as part of the foundation’s COVID-19 business resumption plan, which is consistent with the state’s Phase 2 requirements: • The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg • Governor’s Palace • Capitol • Courthouse • Weaver trade shop • Carpenter’s Yard • Peyton Randolph Yard • Colonial Garden • Magazine Yard • Armoury Yard • Brickyard • George Wythe Yard • Custis Square, including tours The Williamsburg Lodge is currently open with additional hospitality operations expanding based on sustainable business demand. -

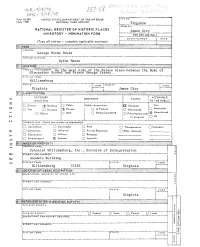

NOMINATION FORM for NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER Dal"E

_, i.. t, 'I . •I · Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF fHE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NA Tl ON Al PARK SERVICE Virginia COUNTY, NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES James City INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DAl"E COMMON: George Wythe House ANOI OR HISTORIC, Wythe House ,__ -·-· -·-:-",-,_:,v.•.,'.•.'c:'. •i•:?-,•· \/:c+i,)"!;)'.(' :{/(;".;.\p; LC '<it\:\ STREET ANo NUMBER: On the west side of the Palace Green between the Duke of Gloucester Street and Prince George Street. --CITY -OR-------------------------------------------------1 TOWN: Williamsburg STATE COOE COUNTY · CODE Virginia •--·-:•, .,. .. __ . 1):\;¢tAs~iFiC:.Xi'tqif :_/</ >:Y /- :· T'•• .. _.L: <> , <f %%\Xfr ;?\ '" _.,..,. ., ....., .___ _ : -:-: : .•:-. ··:::-:;:.':• .;;(:;}'.)\:;:.~:y CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC z D District rn Bui /ding D Public I Public Acquisitil>n: n Occupiod Yes; 0 Restricted D Sile 0 Structu,e rn PriYate 0 In Process 0 Unoccupied D Both 0 Beir,g Con~id&red Unrestricted 0 Object 0 0 Pr&s&rvation work \ ixJ 1- in progr&ss \ D No u PRESENT USE (CJ>eck on~ or More BS Appropr/eto) D Agricultura l D Government 0 Pork 0 Trol'\sportatl on 0 Comm&nts 0 Commercial 0 Industrial 0 Pr/vote Residenco 0 Other ($pt,c/!y) D Educational D M;J itary 0 R&ligiou• D Entorta i rimenf ~ Museum 0 Scientific OWNEA' s NAME: -I"' ), Colonial Williamsburg, Inc., Division of Interpretation -I "1 w Sl"AEET AND NUMBER: UJ Goodwin Building CITY OR TOWN : STATE< CODE Willi4msburg 23185 Virginia ~~~l~'OF'.t{fi~Wtl'.]~~p'rtl&:i'.:L9~/ --._. -

Colonial Capitals of the Dominion of Virginia

NYPL RESEARCH LIBRARIES 3 3433 08188290 8 /re X Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/colonialcapitalsOOfost I JAIIESTOWX TOWER. COLONIAL CAPITALS of'ihe DOMINION of VIRGINIA By MARY L. FOSTER Williamsburg, Va. BRIEF HISTORICAL SKETCHES AND TRADITIONS OF JAMESTOWN, WILLIAMSBURG, YORKTOWN AND THEIR VICINITY ILLUSTRATED WITH A MAP AND PHOTOGRAPHS K>?^K^K>K^K^Hr>K»Hr»K>K^ "UNO AVULSO NON DEFICIT ALTER" fl^- y J. P. BELL COMPANY, INC. PEIINTEES, LYNCHBUBG, VA. Copyright, 1908 Bt MARY L. FOSTER Prrfar^ N giving this little volume of sketches to the public, it has been the author's pur- pose to describe the historic ruins and buildings as they appear at the present time, and at the same time to make them as original and pleasing as possible by lightening their history with the anec- dotes and traditions which have been handed down throughout the years. The information as to the original sites and grants made to the early inhabitants of Jamestown has been largely de- rived from "The Site of Old 'James Towne,' 1607-1698," by Samuel H. Yioung. The author vdshes to express her indebtedness also to Dr. Lyon Gr. Tyler and Eev. W. A. K. Goodwin for assistance rendered in "The Cradle of the Re- public," William and Mary College Quarterlies, and the "Historical Sketch of Bruton Church," and with grateful appreciation to acknowledge the kindness of Dr. J. Leslie Hall, through whose hands the proof sheets have passed. Mary L. Foster. i^itrattnn ©0 iig ilotll^r, uiljo Ijaa faff« tng tnapiratiott attb gutJip, lIjtB Itttb book t0 affierttottafelg JiplJtratfb.