PN02.05Pg52-56.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Lateral Sclerosis, Upper Motor Neuron Dominant Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia

brain sciences Review Upper Motor Neuron Disorders: Primary Lateral Sclerosis, Upper Motor Neuron Dominant Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia Timothy Fullam and Jeffrey Statland * Department of Neurology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas, KS 66160, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Following the exclusion of potentially reversible causes, the differential for those patients presenting with a predominant upper motor neuron syndrome includes primary lateral sclerosis (PLS), hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP), or upper motor neuron dominant ALS (UMNdALS). Differentiation of these disorders in the early phases of disease remains challenging. While no single clinical or diagnostic tests is specific, there are several developing biomarkers and neuroimaging technologies which may help distinguish PLS from HSP and UMNdALS. Recent consensus diagnostic criteria and use of evolving technologies will allow more precise delineation of PLS from other upper motor neuron disorders and aid in the targeting of potentially disease-modifying therapeutics. Keywords: primary lateral sclerosis; amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; hereditary spastic paraplegia Citation: Fullam, T.; Statland, J. Upper Motor Neuron Disorders: Primary Lateral Sclerosis, Upper 1. Introduction Motor Neuron Dominant Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893) and Wilhelm Erb (1840–1921) are credited with first Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and describing a distinct clinical syndrome of upper motor neuron (UMN) tract degeneration in Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia. Brain isolation with symptoms including spasticity, hyperreflexia, and mild weakness [1,2]. Many Sci. 2021, 11, 611. https:// of the earliest described cases included cases of hereditary spastic paraplegia, amyotrophic doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11050611 lateral sclerosis, and underrecognized structural, infectious, or inflammatory etiologies for upper motor neuron dysfunction which have since become routinely diagnosed with the Academic Editors: P. -

Management of Neurogenic Dysphagia

694 Postgrad Med J 2001;77:694–699 Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pmj.77.913.694 on 1 November 2001. Downloaded from Management of neurogenic dysphagia A M O Bakheit Dysphagia is common in patients with neuro- of the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, brain logical disorders. It may result from lesions in stem, cerebellum, and lower cranial nerves may the central or peripheral nervous system as well result in dysphagia. Degeneration of the as from diseases of muscle and disorders of the myenteric ganglion cells in the oesophagus, neuromuscular junction. Drugs that are com- muscle diseases and disorders of neuromusc- monly used in the management of neurological ular transmission, for example myasthenia conditions may also precipitate or aggravate gravis and Eaton-Lambers syndrome, are other swallowing diYculties in some patients. Neuro- less common causes. genic dysphagia often results in serious compli- cations, including pulmonary aspiration, dehy- CEREBRAL CORTEX dration, and malnutrition. These The commonest condition associated with complications are usually preventable if the dysphagia resulting from cortical lesions is stroke. Acute stroke is complicated by dys- dysphagia is recognised early and managed 1 appropriately. phagia in about 25%–42% of all cases. Dysphagia in these patients is usually associ- Physiological mechanisms of neurogenic ated with hemiplegia due to lesions of the brain stem or the involvement of one or both dysphagia The act of swallowing may be viewed as three hemispheres. However, on rare occasions, dys- discrete but inter-related physiological stages: phagia may be the sole manifestation of a cer- the oral, pharyngeal, and oesophageal phases. -

ICD9 & ICD10 Neuromuscular Codes

ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM NEUROMUSCULAR DIAGNOSIS CODES ICD-9-CM ICD-10-CM Focal Neuropathy Mononeuropathy G56.00 Carpal tunnel syndrome, unspecified Carpal tunnel syndrome 354.00 G56.00 upper limb Other lesions of median nerve, Other median nerve lesion 354.10 G56.10 unspecified upper limb Lesion of ulnar nerve, unspecified Lesion of ulnar nerve 354.20 G56.20 upper limb Lesion of radial nerve, unspecified Lesion of radial nerve 354.30 G56.30 upper limb Lesion of sciatic nerve, unspecified Sciatic nerve lesion (Piriformis syndrome) 355.00 G57.00 lower limb Meralgia paresthetica, unspecified Meralgia paresthetica 355.10 G57.10 lower limb Lesion of lateral popiteal nerve, Peroneal nerve (lesion of lateral popiteal nerve) 355.30 G57.30 unspecified lower limb Tarsal tunnel syndrome, unspecified Tarsal tunnel syndrome 355.50 G57.50 lower limb Plexus Brachial plexus lesion 353.00 Brachial plexus disorders G54.0 Brachial neuralgia (or radiculitis NOS) 723.40 Radiculopathy, cervical region M54.12 Radiculopathy, cervicothoracic region M54.13 Thoracic outlet syndrome (Thoracic root Thoracic root disorders, not elsewhere 353.00 G54.3 lesions, not elsewhere classified) classified Lumbosacral plexus lesion 353.10 Lumbosacral plexus disorders G54.1 Neuralgic amyotrophy 353.50 Neuralgic amyotrophy G54.5 Root Cervical radiculopathy (Intervertebral disc Cervical disc disorder with myelopathy, 722.71 M50.00 disorder with myelopathy, cervical region) unspecified cervical region Lumbosacral root lesions (Degeneration of Other intervertebral disc degeneration, -

Serial Magnetic Resonance Imaging Changes of Pseudotumor Lesions In

Yan et al. BMC Neurol (2021) 21:219 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02250-4 CASE REPORT Open Access Serial magnetic resonance imaging changes of pseudotumor lesions in retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukoencephalopathy and systemic manifestations: a case report Yuying Yan1, Shuai Jiang1, Ruilin Wang2, Xiang Wang3, Peng Li3* and Bo Wu1* Abstract Background: Retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukoencephalopathy and systemic manifestations (RVCL-S) is an adult-onset rare monogenic microvasculopathy. Its typical neuroimaging features are punctate white matter lesions or pseudotumor alterations. RVCL-S is often under-recognized and misdiagnosed because of its rarity and similar imaging manifestations to multiple sclerosis or brain malignant mass. Case presentation: Here we report a case of a 36-year-old Chinese man who developed multiple tumefactive brain lesions spanning over two years leading to motor aphasia, cognitive decline, and limb weakness. He also presented with slight vision loss, and fundus fuorescein angiography indicated retinal vasculopathy. He underwent brain biopsies twice and showed no evidence of malignancy. Given the family history that his father died of a brain mass of unclear etiology, RVCL-S was suspected, and genetic analysis confrmed the diagnosis with a heterozygous insertion mutation in the three-prime repair exonuclease 1 gene. He was given courses of corticosteroids and cyclophospha- mide but received little response. Conclusions: The present case is one of the few published reports of RVCL-S with two-year detailed imaging data. Serial magnetic resonance images showed the progression pattern of the lesions. Our experience emphasizes that a better understanding of RVCL-S and considering it as a diferential diagnosis in patients with tumefactive brain lesions may help avoid unnecessary invasive examinations and make an earlier diagnosis. -

Radiologically Isolated Syndrome: a Review for Neuroradiologists

REVIEW ARTICLE Radiologically Isolated Syndrome: A Review for Neuroradiologists M. Hosseiny, S.D. Newsome, and D.M. Yousem ABSTRACT SUMMARY: Radiologically isolated syndrome refers to an entity in which white matter lesions fulfilling the criteria for multiple sclerosis occur in individuals without a history of a clinical demyelinating attack or alternative etiology. Since its introduction in 2009, the diagnostic criteria of radiologically isolated syndrome and its clinical relevance have been widely debated by neu- rologists and radiologists. The aim of the present study was to review the following: 1) historical evolution of radiologically iso- lated syndrome criteria, 2) clinical and imaging findings in adults and children with radiologically isolated syndrome, 3) imaging features of patients with radiologically isolated syndrome at high risk for conversion to MS, and 4) challenges and controversies for work-up, management, and therapeutic interventions of patients with radiologically isolated syndrome. ABBREVIATIONS: CIS ¼ clinically isolated syndrome; DIS ¼ dissemination in space; DIT ¼ dissemination in time; MAGNIMS ¼ Magnetic Resonance Imaging in MS; RIS ¼ radiologically isolated syndrome; RRMS ¼ relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; CADASIL ¼ cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with sub- cortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy; ADEM ¼ acute disseminated encephalomyelitis adiologically isolated syndrome (RIS) refers to an entity in patients are being evaluated for headache, trauma, or nonspecific Rwhich brain or spine MR -

History-Of-Movement-Disorders.Pdf

Comp. by: NJayamalathiProof0000876237 Date:20/11/08 Time:10:08:14 Stage:First Proof File Path://spiina1001z/Womat/Production/PRODENV/0000000001/0000011393/0000000016/ 0000876237.3D Proof by: QC by: ProjectAcronym:BS:FINGER Volume:02133 Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol. 95 (3rd series) History of Neurology S. Finger, F. Boller, K.L. Tyler, Editors # 2009 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved Chapter 33 The history of movement disorders DOUGLAS J. LANSKA* Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Tomah, WI, USA, and University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI, USA THE BASAL GANGLIA AND DISORDERS Eduard Hitzig (1838–1907) on the cerebral cortex of dogs OF MOVEMENT (Fritsch and Hitzig, 1870/1960), British physiologist Distinction between cortex, white matter, David Ferrier’s (1843–1928) stimulation and ablation and subcortical nuclei experiments on rabbits, cats, dogs and primates begun in 1873 (Ferrier, 1876), and Jackson’s careful clinical The distinction between cortex, white matter, and sub- and clinical-pathologic studies in people (late 1860s cortical nuclei was appreciated by Andreas Vesalius and early 1870s) that the role of the motor cortex was (1514–1564) and Francisco Piccolomini (1520–1604) in appreciated, so that by 1876 Jackson could consider the the 16th century (Vesalius, 1542; Piccolomini, 1630; “motor centers in Hitzig and Ferrier’s region ...higher Goetz et al., 2001a), and a century later British physician in degree of evolution that the corpus striatum” Thomas Willis (1621–1675) implicated the corpus -

Deep Brain Stimulation in the Treatment of Dyskinesia and Dystonia

Neurosurg Focus 17 (1):E2, 2004, Click here to return to Table of Contents Deep brain stimulation in the treatment of dyskinesia and dystonia HIROKI TODA, M.D., PH.D., CLEMENT HAMANI, M.D., PH.D., AND ANDRES LOZANO, M.D., PH.D., F.R.C.S.(C) Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, Toronto Western Hospital, University of Toronto, Ontario, Cananda Deep brain stimulation (DBS) has become a mainstay of treatment for patients with movement disorders. This modality is directed at modulating pathological activity within basal ganglia output structures by stimulating some of their nuclei, such as the subthalamic nucleus (STN) and the globus pallidus internus (GPi), without making permanent lesions. With the accumulation of experience, indications for the use of DBS have become clearer and the effective- ness and limitations of this form of therapy in different clinical conditions have been better appreciated. In this review the authors discuss the efficacy of DBS in the treatment of dystonia and levodopa-induced dyskinesias. The use of DBS of the STN and GPi is very effective for the treatment of movement disorders induced by levodopa. The relative ben- efits of using the GPi as opposed to the STN as a target are still being investigated. Bilateral GPi stimulation is gain- ing importance in the therapeutic armamentarium for the treatment of dystonia. The DYT1 forms of generalized dys- tonia and cervical dystonias respond to DBS better than secondary dystonia does. Discrimination between the diverse forms of dystonia and a better understanding of the pathophysiological features of this condition will serve as a plat- form for improved outcomes. -

THE SYNDROMES of the ARTERIES of the BRAIN and SPINAL CORD Part 1 by LESLIE G

65 Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.29.328.65 on 1 February 1953. Downloaded from THE SYNDROMES OF THE ARTERIES OF THE BRAIN AND SPINAL CORD Part 1 By LESLIE G. KILOH, M.D., M.R.C.P., D.P.M. First Assistant in the Joint Department of Psychological Medicine, Royal Victoria Infirmary and University of Durham Introduction general circulatory efficiency at the time of the Little interest is shown at present in the syn- catastrophe is of the greatest importance. An dromes of the arteries of the brain and spinal cord, occlusion, producing little effect in the presence of and this perhaps is related to the tendency to a normal blood pressure, may cause widespread minimize the importance of cerebral localization. pathological changes if hypotension co-exists. Yet these syndromes are far from being fully A marked discrepancy has been noted between elucidated and understood. It must be admitted the effects of ligation and of spontaneous throm- that in many cases precise localization is often of bosis of an artery. The former seldom produces little more than academic interest and ill effects whilst the latter frequently determines provides Protected by copyright. nothing but a measure of personal satisfaction to infarction. This is probably due to the tendency the physician. But it is worth recalling that the of a spontaneous thrombus to extend along the detailed study of the distribution of the bronchi affected vessel, sealing its branches and blocking and of the pathological anatomy of congenital its collateral circulation, and to the fact that the abnormalities of the heart, was similarly neglected arterial disease is so often generalized. -

Part Ii – Neurological Disorders

Part ii – Neurological Disorders CHAPTER 14 MOVEMENT DISORDERS AND MOTOR NEURONE DISEASE Dr William P. Howlett 2012 Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, Moshi, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania BRIC 2012 University of Bergen PO Box 7800 NO-5020 Bergen Norway NEUROLOGY IN AFRICA William Howlett Illustrations: Ellinor Moldeklev Hoff, Department of Photos and Drawings, UiB Cover: Tor Vegard Tobiassen Layout: Christian Bakke, Division of Communication, University of Bergen E JØM RKE IL T M 2 Printed by Bodoni, Bergen, Norway 4 9 1 9 6 Trykksak Copyright © 2012 William Howlett NEUROLOGY IN AFRICA is freely available to download at Bergen Open Research Archive (https://bora.uib.no) www.uib.no/cih/en/resources/neurology-in-africa ISBN 978-82-7453-085-0 Notice/Disclaimer This publication is intended to give accurate information with regard to the subject matter covered. However medical knowledge is constantly changing and information may alter. It is the responsibility of the practitioner to determine the best treatment for the patient and readers are therefore obliged to check and verify information contained within the book. This recommendation is most important with regard to drugs used, their dose, route and duration of administration, indications and contraindications and side effects. The author and the publisher waive any and all liability for damages, injury or death to persons or property incurred, directly or indirectly by this publication. CONTENTS MOVEMENT DISORDERS AND MOTOR NEURONE DISEASE 329 PARKINSON’S DISEASE (PD) � � � � � � � � � � � -

A Diffusion Tensor Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study of Brain Tissue from Patients with Migraine M a Rocca, B Colombo, M Inglese, M Codella, G Comi, M Filippi

501 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.74.4.501 on 1 April 2003. Downloaded from SHORT REPORT A diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging study of brain tissue from patients with migraine M A Rocca, B Colombo, M Inglese, M Codella, G Comi, M Filippi ............................................................................................................................. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:501–503 PATIENTS AND METHODS Objective: To measure in vivo, using diffusion tensor mag- We studied 34 patients (31 women and three men; mean age netic resonance imaging (DT-MRI) the extent of pathologi- 35.2 years, range 18–55 years; mean duration of the disease cal damage of normal appearing brain tissue (NABT) from 13.6 years, range 1–40 years; mean number of episodes per patients with migraine. year 44.6, range 12–70) with migraine.10 All possible alterna- Methods: Dual echo and DT-MRI scans of the brain were tive diagnoses were carefully excluded.10 There were 28 acquired from 34 patients with migraine and 17 sex and patients affected by “migraine without aura” and six patients age matched healthy volunteers. Mean diffusivity (MD) affected by “migraine with aura”.10 Patients with hyper- and fractional anisotropy (FA) histograms of the NABT tension, hypercholesteraemia, diabetes mellitus, vascular/ were obtained from all subjects and the histograms’ peak heart diseases, and other major systemic and neurological heights and average NABT MD and FA measured. When conditions were excluded. At the time of the MRI assessment, present, average MD and FA values of T2 visible lesions 11 patients were treated with prophylactic drugs. Seventeen were also measured. -

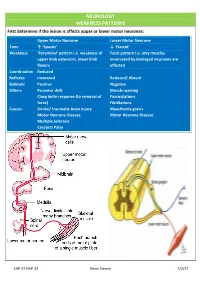

NEUROLOGY WEAKNESS PATTERNS First Determine If the Lesion Is Affects Upper Or Lower Motor Neurones

NEUROLOGY WEAKNESS PATTERNS First determine if the lesion is affects upper or lower motor neurones: Upper Motor Neurone Lower Motor Neurone Tone ↑ ‘Spastic’ ↓ ‘Flaccid’ Weakness ‘Pyramidal’ pattern i.e. weakness of Focal pattern i.e. only muscles upper limb extensors, lower limb innervated by damaged neurones are flexors affected Coordination Reduced Reflexes Increased Reduced/ Absent Babinski Positive Negative Others Pronator drift Muscle wasting Clasp knife response (to removal of Fasciculations force) Fibrillations Causes Stroke/ traumatic brain injury Myasthenia gravis Motor Neurone Disease Motor Neurone Disease Multiple Sclerosis Cerebral Palsy CAP 37 HAP 33 Kevin Gervin 7/2/17 What do we mean by extrapyramidal? Extrapyramidal symptoms Symptoms affecting tracts other than corticospinal and corticobulbar Extrapyramidal tracts don’t travel through the medullary pyramids The system regulates posture and muscle tone so pathology usually leads to movement disorders Most common cause is typical antipsychotics affecting Dopamine (D2) receptors e.g. haloperidol Treatment is anticholinergics e.g. procyclidine Extrapyramidal conditions: Acute dystonic reactions → muscle spasms e.g. neck, jaw, back. Akathisia- feeling of internal restlessness Drug induced Parkinsonism- tremor, rigidity etc. Tardive dyskinesia- involuntary muscle movements of lower face and extremities, often permanent What’s the difference between a Bulbar and Pseudobulbar palsy? Bulbar Pseudobulbar Pathophysiology LMN lesion CN V, VII, IX- XII Disease of corticobulbar -

Isolated Facial Palsy: a New Lacunar Syndrome

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.47.1.84 on 1 January 1984. Downloaded from Journal ofNeurology, Neurosuirgery, and Psychiatry 1984;47: 84-86 Short report Isolated facial palsy: a new lacunar syndrome CHENYA HUANG, GERALD BROE From the Department ofMedicine, University ofHong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong and Department ofNeurology, Lidcombe Hospital, Lidcombe, Australia SUMMARY Three cases of sudden isolated upper motor neuron facial palsy and two with associated pseudobulbar palsy have been seen. All were without significant limb weakness. Computed tomography demonstrated small deep infarcts in the internal capsular/corona radiata regions. Pure upper motor neuron facial palsy may be another lacunar syndrome, due to a lesion in the internal capsule or corona radiata. palsies are lower motor neuron lesions. On examination blood pressure was 130/90 mm Hg. He Most facial facial paresis, complete an isolated facial palsy is seen had a left upper motor neuron Occasionally however, and aphagia. Jaw jerk was not increased. Tone, motor neuron in nature. anarthria which appears to be upper power, coordination and sensation were normal; however Protected by copyright. Prior to the availability of CT scan, the site of such the patient veered slightly to the left on walking. CSF lesion was unknown. Some have been ascribed to examination showed 1 mononuclear cell/mm' with normal peripheral facial nerve lesions. ' Puvenendren, Wong biochemistry and serology. EMG of facial muscles showed and Ransome described in 1979 five patients with no abnormality. CT scan showed small low density lesions sudden onset of dysarthria, dysphagia and upper bilaterally in the region of corona radiata adjacent to the motor neuron facial palsy.' EEG and isotope scans basal ganglia (fig 1).