Wayne Heisler Jr, the Ballet Collaborations of Richard Strauss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

Download Booklet

570895bk RStrauss US:557541bk Kelemen 3+3 3/8/09 8:42 PM Page 1 Antoni Wit Staatskapelle Weimar Antoni Wit, one of the most highly regarded Polish conductors, studied conducting with Founded in 1491, the Staatskapelle Weimar is one of the oldest orchestras in the world, its reputation inextricably linked Richard Henryk Czyz˙ and composition with Krzysztof Penderecki at the Academy of Music in to some of the greatest works and musicians of all time. Franz Liszt, court music director in the mid-nineteenth Kraków, subsequently continuing his studies with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. He also century, helped the orchestra gain international recognition with premières that included Wagner’s Lohengrin in graduated in law at the Jagellonian University in Kraków. Immediately after completing 1850. As Weimar’s second music director, Richard Strauss conducted first performances of Guntram and STRAUSS his studies he was engaged as an assistant at the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra by Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel. The orchestra was also the first to perform Strauss’s Don Juan, Macbeth and Death Witold Rowicki and was later appointed conductor of the Poznan´ Philharmonic. He and Transfiguration. After World War II Hermann Abendroth did much to restore the orchestra’s former status and Symphonia domestica collaborated with the Warsaw Grand Theatre, and from 1974 to 1977 was artistic director quality, ultimately establishing it as one of Germany’s leading orchestras. The Staatskapelle Weimar cultivates its of the Pomeranian Philharmonic, before his appointment as director of the Polish Radio historic tradition today, while exploring innovative techniques and wider repertoire, as reflected in its many recordings. -

Ariadne Auf Naxos: a Study in Transformation Through Contrast and Coalescence

Ariadne auf Naxos: A Study in Transformation through Contrast and Coalescence By Copyright 2015 Etta Fung Submitted to the graduate degree program in Vocal Performance and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Julia Broxholm ________________________________ Paul Laird ________________________________ David Alan Street ________________________________ Joyce Castle ________________________________ Michelle Heffner Hayes Date Defended: 5/4/2015 i The Thesis Committee for Etta Fung certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Ariadne auf Naxos: A Study in Transformation through Contrast and Coalescence _______________________________ Chairperson Julia Broxholm Date approved: 5/13/15 ii Abstract Ariadne auf Naxos, by composer Richard Strauss and librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal, concerns the simultaneous performance of a tragedy and a comedy at a rich man’s house in Vienna, and the conflicts that arise between the two groups. The primary focus of this paper is the character Zerbinetta, a coloratura soprano who is the main performer in the commedia dell’arte troupe. Following consideration of the opera’s historical background, the first segment of this paper examines Zerbinetta’s duet with the young Composer starting from “Nein Herr, so kommt es nicht…” in the Prologue, which reveals her coquettish yet complex character. The second section offers a detailed description of her twelve-minute aria “Großmächtige Prinzessin” in the opera, exploring the show’s various levels of satire. The last segment is an investigation of the differing perspectives of the performers and the audience during Zerbinetta’s tour de force. -

Der Rosenkavalier by Richard Strauss

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 Octavian and the Composer: Principal Male Roles in Opera Composed for the Female Voice by Richard Strauss Melissa Lynn Garvey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC OCTAVIAN AND THE COMPOSER: PRINCIPAL MALE ROLES IN OPERA COMPOSED FOR THE FEMALE VOICE BY RICHARD STRAUSS By MELISSA LYNN GARVEY A Treatise submitted to the Department of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2010 The members of the committee approve the treatise of Melissa Lynn Garvey defended on April 5, 2010. __________________________________ Douglas Fisher Professor Directing Treatise __________________________________ Seth Beckman University Representative __________________________________ Matthew Lata Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I’d like to dedicate this treatise to my parents, grandparents, aunt, and siblings, whose unconditional love and support has made me the person I am today. Through every attended recital and performance, and affording me every conceivable opportunity, they have encouraged and motivated me to achieve great things. It is because of them that I have reached this level of educational achievement. Thank you. I am honored to thank my phenomenal husband for always believing in me. You gave me the strength and courage to believe in myself. You are everything I could ever ask for and more. Thank you for helping to make this a reality. -

Richard Strauss's Ariadne Auf Naxos

Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos - A survey of the major recordings by Ralph Moore Ariadne auf Naxos is less frequently encountered on stage than Der Rosenkavalier or Salome, but it is something of favourite among those who fancy themselves connoisseurs, insofar as its plot revolves around a conceit typical of Hofmannsthal’s libretti, whereby two worlds clash: the merits of populist entertainment, personified by characters from the burlesque Commedia dell’arte tradition enacting Viennese operetta, are uneasily juxtaposed with the claims of high art to elevate and refine the observer as embodied in the opera seria to be performed by another company of singers, its plot derived from classical myth. The tale of Ariadne’s desertion by Theseus is performed in the second half of the evening and is in effect an opera within an opera. The fun starts when the major-domo conveys the instructions from “the richest man in Vienna” that in order to save time and avoid delaying the fireworks, both entertainments must be performed simultaneously. Both genres are parodied and a further contrast is made between Zerbinetta’s pragmatic attitude towards love and life and Ariadne’s morbid, death-oriented idealism – “Todgeweihtes Herz!”, Tristan und Isolde-style. Strauss’ scoring is interesting and innovative; the orchestra numbers only forty or so players: strings and brass are reduced to chamber-music scale and the orchestration heavily weighted towards woodwind and percussion, with the result that it is far less grand and Romantic in scale than is usual in Strauss and a peculiarly spare ad spiky mood frequently prevails. -

A Mythic Heroine in <I> Der Rosenkavalier </I>

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 11 | Issue 1 Article 3 A Mythic Heroine in Der Rosenkavalier Bridget Ramzy Wilfrid Laurier University Recommended Citation Ramzy, Bridget (2018) "A Mythic Heroine in Der Rosenkavalier ," Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology: Vol. 11: Iss. 1, Article 3. A Mythic Heroine in Der Rosenkavalier Abstract This paper explores the Allomatische—Strauss and Hofmannsthal's concept of transformation by means of taking risk—through its application to Der Rosenkavalier's Marie-Therese (the Marschallin). The Allomatische’s very apparent presence throughout Strauss and Hofmannsthal’s collaborations in their “mythic” operas, urges its examination in Der Rosenkavlier. This paper explores the Marschallin's risk in context of gender, arguing that her self-acceptance as an ageing woman is an exceedingly brave act, that in-turn transforms her. In this paper, a character study of the Marschallin in Act I before the transformation, and after in Act III is presented and corroborated by interspersed musical examples. A comparison with other characters, both male and female, further establishes the gendered context of the Marschallin's risk. In conclusion, the Marschallin's brave risk of self-acceptance as an aging woman transforms her, and places her in the pantheon of Strauss and Hofmannsthal's mythic heroines. Keywords opera, gender, Der Rosenkavalier, the Marschallin, Richard Strauss A Mythic Heroine A Mythic Heroine in Der Rosenkavalier Bridget Ramzy Year II – Wilfrid Laurier University Richard Strauss and Hugo von Hofmannsthal were fascinated with the theme of transformation. Two of Strauss's tone poems, Tod und Verklärung and Eine Alpensinphonie, deal with the subject, and it is central in many of Strauss and Hofmannsthal’s collaborative works.1 Hofmannsthal wrote, “Transformation is the life of life itself, the real mystery of nature as creative force. -

View Program

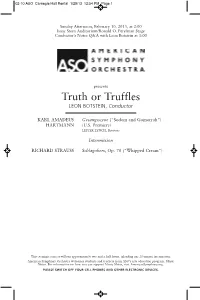

02-10 ASO_Carnegie Hall Rental 1/29/13 12:54 PM Page 1 Sunday Afternoon, February 10, 2013, at 2:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 1:00 presents Truth or Truffles LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor KARL AMADEUS Gesangsszene (“Sodom and Gomorrah”) HARTMANN (U.S. Premiere) LESTER LYNCH, Baritone Intermission RICHARD STRAUSS Schlagobers, Op. 70 (“Whipped Cream”) This evening’s concert will run approximately two and a half hours, inlcuding one 20-minute intermission. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes students and teachers from ASO’s arts education program, Music Notes. For information on how you can support Music Notes, visit AmericanSymphony.org. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. 02-10 ASO_Carnegie Hall Rental 1/29/13 12:54 PM Page 2 THE Program KARL AMADEUS HARTMANN Gesangsszene Born August 2, 1905, in Munich Died December 5, 1963, in Munich Composed in 1962–63 Premiered on November 12, 1964, in Frankfurt, by the orchestra of the Hessischer Rundfunk under Dean Dixon with soloist Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, for whom it was written Performance Time: Approximately 27 minutes Instruments: 3 flutes, 2 piccolos, alto flute, 3 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 3 French horns, 3 trumpets, piccolo trumpet, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, gong, chimes, cymbals, tamtam, tambourine, tomtoms, timbales, field drum, snare drum, bass drum, glockenspiel, xylophone, vibraphone, marimba), harp, celesta, piano, strings, -

THROUGH LIFE and LOVE Richard Strauss

THROUGH LIFE AND LOVE Richard Strauss Louise Alder soprano Joseph Middleton piano Richard Strauss (1864-1949) THROUGH LIFE AND LOVE Youth: Das Mädchen 1 Nichts 1.40 Motherhood: Mutterschaft 2 Leises Lied 3.13 16 Muttertänderlei 2.27 3 Ständchen 2.42 17 Meinem Kinde 2.52 4 Schlagende Herzen 2.29 5 Heimliche Aufforderung 3.16 Loss: Verlust 18 Die Nacht 3.02 Longing: Sehnsucht 19 Befreit 4.54 6 Sehnsucht 4.27 20 Ruhe, meine Seele! 3.54 7 Waldseligkeit 2.54 8 Ach was Kummer, Qual und Schmerzen 2.04 Release: Befreiung 9 Breit’ über mein Haupt 1.47 21 Zueignung 1.49 Passions: Leidenschaft 22 Weihnachtsgefühl 2.26 10 Wie sollten wir geheim sie halten 1.54 23 Allerseelen 3.22 11 Das Rosenband 3.15 12 Ich schwebe 2.03 Total time 64.48 Partnership: Liebe Louise Alder soprano 13 Nachtgang 3.01 Joseph Middleton piano 14 Einerlei 2.53 15 Rote Rosen 2.19 2 Singing Strauss Coming from a household filled with lush baroque music as a child, I found Strauss a little later in my musical journey and vividly remember how hard I fell in love with a recording of Elisabeth Schwarzkopf singing Vier Letze Lieder, aged about 16. I couldn’t believe from the beginning of the first song it could possibly get any more ecstatic and full of emotion, and yet it did. It was a short step from there to Strauss opera for me, and with the birth of YouTube I sat until the early hours of many a morning in my tiny room at Edinburgh University, listening to, watching and obsessing over Der Rosenkavalier’s final trio and presentation of the rose. -

An Examination of Stylistic Elements in Richard Strauss's Wind Chamber Music Works and Selected Tone Poems Galit Kaunitz

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 An Examination of Stylistic Elements in Richard Strauss's Wind Chamber Music Works and Selected Tone Poems Galit Kaunitz Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC AN EXAMINATION OF STYLISTIC ELEMENTS IN RICHARD STRAUSS’S WIND CHAMBER MUSIC WORKS AND SELECTED TONE POEMS By GALIT KAUNITZ A treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Galit Kaunitz defended this treatise on March 12, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Eric Ohlsson Professor Directing Treatise Richard Clary University Representative Jeffrey Keesecker Committee Member Deborah Bish Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii This treatise is dedicated to my parents, who have given me unlimited love and support. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee members for their patience and guidance throughout this process, and Eric Ohlsson for being my mentor and teacher for the past three years. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ vi Abstract -

I Urban Opera: Navigating Modernity Through the Oeuvre of Strauss And

Urban Opera: Navigating Modernity through the Oeuvre of Strauss and Hofmannsthal by Solveig M. Heinz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Germanic Languages and Literatures) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Vanessa H. Agnew, Chair Associate Professor Naomi A. André Associate Professor Andreas Gailus Professor Julia C. Hell i For John ii Acknowledgements Writing this dissertation was an intensive journey. Many people have helped along the way. Vanessa Agnew was the most wonderful Doktormutter a graduate student could have. Her kindness, wit, and support were matched only by her knowledge, resourcefulness, and incisive critique. She took my work seriously, carefully reading and weighing everything I wrote. It was because of this that I knew my work and ideas were in good hands. Thank you Vannessa, for taking me on as a doctoral rookie, for our countless conversations, your smile during Skype sessions, coffee in Berlin, dinners in Ann Arbor, and the encouragement to make choices that felt right. Many thanks to my committee members, Naomi André, Andreas Gailus, and Julia Hell, who supported the decision to work with the challenging field of opera and gave me the necessary tools to succeed. Their open doors, email accounts, good mood, and guiding feedback made this process a joy. Mostly, I thank them for their faith that I would continue to work and explore as I wrote remotely. Not on my committee, but just as important was Hartmut. So many students have written countless praises of this man. I can only concur, he is simply the best. -

Interpreting Race and Difference in the Operas of Richard Strauss By

Interpreting Race and Difference in the Operas of Richard Strauss by Patricia Josette Prokert A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Jane F. Fulcher, Co-Chair Professor Jason D. Geary, Co-Chair, University of Maryland School of Music Professor Charles H. Garrett Professor Patricia Hall Assistant Professor Kira Thurman Patricia Josette Prokert [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-4891-5459 © Patricia Josette Prokert 2020 Dedication For my family, three down and done. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family― my mother, Dev Jeet Kaur Moss, my aunt, Josette Collins, my sister, Lura Feeney, and the kiddos, Aria, Kendrick, Elijah, and Wyatt―for their unwavering support and encouragement throughout my educational journey. Without their love and assistance, I would not have come so far. I am equally indebted to my husband, Martin Prokert, for his emotional and technical support, advice, and his invaluable help with translations. I would also like to thank my doctorial committee, especially Drs. Jane Fulcher and Jason Geary, for their guidance throughout this project. Beyond my committee, I have received guidance and support from many of my colleagues at the University of Michigan School of Music, Theater, and Dance. Without assistance from Sarah Suhadolnik, Elizabeth Scruggs, and Joy Johnson, I would not be here to complete this dissertation. In the course of completing this degree and finishing this dissertation, I have benefitted from the advice and valuable perspective of several colleagues including Sarah Suhadolnik, Anne Heminger, Meredith Juergens, and Andrew Kohler. -

Cynthia Cook Mezzo-Soprano

Cynthia Cook Mezzo-Soprano Cynthia Cook is the epitome of the modern bel canto mezzo soprano. Her large, lush voice, impeccable use of florid agility and her natural beauty serve her well in all of her repertoire. In 2016/17, she performed the dual roles of Baroness/Vanderdendur in Candide at Opéra National de Bordeaux and Théâtre du Capitole Toulouse. In 2014, she gave a shining performance in the lead role of Sondra Finchley in the World Premiere of the newly revised version of Tobias Picker’s An American Tragedy at Glimmerglass Festival where she returned this past year to play Baroness and Vanderdendur in Candide. In previous years, she continued her work with Francesca Zambello in Washington National Opera’s new production of Dialogues of the Carmelites as a Carmelite Nun while covering the role of Mother Marie, and sang the mezzo solo in Rachmaninov’s Vespers with Princeton Pro Musica. Cynthia Cook has received training and performed leading roles with some of the most prestigious Young Artist programs in the United States. At Florida Grand Opera, she appeared as Zweite Dame in Die Zauberflöte and Teresa in La Sonnambula (under the direction of Renata Scotto). With the Santa Fe Opera Apprentice Program she covered Calbo in Rossini’s Maometto II and Adelaide in Arabella. In the apprentice scenes concert, she gave a memorable performance as Princess Eboli in the Garden Scene from Don Carlo. A graduate from the renowned Academy of Vocal Arts, she sang a wide range of roles, including: Adalgisa in Norma, Meg Page in Falstaff, Dorabella in Così fan tutte, Zerlina in Don Giovanni, Smeton in Anna Bolena, Clairon in Capriccio, and Adelaide in Arabella.