Of the Conduct of the Understanding Copyright by Paul Schuurman of the Conduct of the Understanding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parte Seconda Bibliotheca Collinsiana, Seu Catalogus Librorum Antonji Collins Armigeri Ordine Alphabetico Digestus

Parte seconda Bibliotheca Collinsiana, seu Catalogus Librorum Antonji Collins Armigeri ordine alphabetico digestus Avvertenza La biblioteca non è solo il luogo della tua memoria, dove conservi quel che hai letto, ma il luogo della memoria universale, dove un giorno, nel momento fata- le, potrai trovare quello che altri hanno letto prima di te. Umberto Eco, La memoria vegetale e altri scritti di bibliografia, Milano, Rovello, 2006 Si propone qui un’edizione del catalogo manoscritto della collezione libra- ria di Anthony Collins,1 la cui prima compilazione egli completò nel 1720.2 Nei nove anni successivi tuttavia Collins ampliò enormemente la sua biblioteca, sin quasi a raddoppiarne il numero delle opere. Annotò i nuovi titoli sulle pagine pari del suo catalogo che aveva accortamente riservato a successive integrazio- ni. Dispose le nuove inserzioni in corrispondenza degli autori già schedati, attento a preservare il più possibile l’ordine alfabetico. Questo tuttavia è talora impreciso e discontinuo.3 Le inesattezze, che ricorrono più frequentemente fra i titoli di inclusione più tarda, devono imputarsi alla difficoltà crescente di annotare nel giusto ordine le ingenti e continue acquisizioni. Sono altresì rico- noscibili abrasioni e cancellature ed in alcuni casi, forse per esigenze di spazio, oppure per sostituire i titoli espunti, i lemmi della prima stesura sono frammez- zati da titoli pubblicati in date successive al 1720.4 In appendice al catalogo, due liste confuse di titoli, per la più parte anonimi, si svolgono l’una nelle pagi- ne dispari e l’altra in quelle pari del volume.5 Agli anonimi seguono sparsi altri 1 Sono molto grato a Francesca Gallori e Barbara Maria Graf per aver contribuito alla revi- sione della mia trascrizione con dedizione e generosità. -

Aaaaannual Review

AAAAAnnual Review Front Cover: The Staffordshire Hoard (see page 27) Reproduced by permission of Birmingham Museum and Art Galleries See www.staffordshirehoard.org.uk Back Cover: Cluster of Quartz Crystals (see page 23) Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society Annual Report and Review 2010 th The 190 Annual Report of the Council at the close of the session 2009-10 Presented to the Annual Meeting held on 8th December 2010 and review of events and grants awarded THE LEEDS PHILOSOPHICAL AND LITERARY SOCIETY, founded in 1819, has played an important part in the cultural life of Leeds and the region. In the nineteenth century it was in the forefront of the intellectual life of the city, and established an important museum in its own premises in Park Row. The museum collection became the foundation of today’s City Museum when in 1921 the Society transferred the building and its contents to the Corporation of Leeds, at the same time reconstituting itself as a charitable limited company, a status it still enjoys today. Following bomb damage to the Park Row building in the Second World War, both Museum and Society moved to the City Museum building on The Headrow, where the Society continued to have its offices until the museum closed in 1998. The new Leeds City Museum, which opened in 2008, is now once again the home of the Society’s office. In 1936 the Society donated its library to the Brotherton Library of the University of Leeds, where it is available for consultation. Its archives are also housed there. The official charitable purpose of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society is (as newly defined in 1997) “To promote the advancement of science, literature and the arts in the City of Leeds and elsewhere, and to hold, give or provide for meetings, lectures, classes, and entertainments of a scientific, literary or artistic nature”. -

Free Will an Extensive Bibliography

Nicholas Rescher Free Will An Extensive Bibliography Nicholas Rescher Free Will An Extensive Bibliography With the Collaboration of Estelle Burris Bibliographic information published by Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de North and South America by Transaction Books Rutgers University Piscataway, NJ 08854-8042 [email protected] United Kingdom, Eire, Iceland, Turkey, Malta, Portugal by Gazelle Books Services Limited White Cross Mills Hightown LANCASTER, LA1 4XS [email protected] Livraison pour la France et la Belgique: Librairie Philosophique J.Vrin 6, place de la Sorbonne; F-75005 PARIS Tel. +33 (0)1 43 54 03 47; Fax +33 (0)1 43 54 48 18 www.vrin.fr 2010 ontos verlag P.O. Box 15 41, D-63133 Heusenstamm www.ontosverlag.com ISBN 978-3-86838-058-3 2010 No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in retrieval systems or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use of the purchaser of the work Printed on acid-free paper FSC-certified (Forest Stewardship Council) This hardcover binding meets the International Library standard Printed in Germany by buch bücher dd ag Free Will Bibliography Contents Introduction i Bibliography 1 FREE WILL BIBLIOGRAPHY INTRODUCTION “While the concept of free will is a favored theme of philosophical deliberation, there nevertheless here enters a one-sidedness, unclarity, and confusion as though a mass of a hundred speakers in a hundred languages were disputing simultaneously, each being absolutely convinced that he alone is altogether clear on the matter and that all the rest are uncomprehending ignoramuses.” —Eduard von Hartmann, The Phenomenology of Moral Consciousness (Berlin, C. -

Governs the Making of Photocopies Or Other Reproductions of Copyrighted Materials

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. Proceedings of The First Munster Symposium on Jonathan Swift Edited by Hermann J. Real and Heinz J. Vienken 1985 Wilhelm Fink Verlag Miinchen Clive T. Probyn Monash University, Clayton, Victoria "Haranguing upon Texts": Swift and the Idea of the Book ABSTRACT. The quotation in the title is taken from Anthony Collins's Discourse ofFree-Thinking (1713), cited by Swift in his Abslract ofMr. C --- - ns '5 Discourse of Free-Thinking (I7 13), the two together offering an example of Swift's parodic method. This paper examines the "refunctioning" of the model text by Swift and suggests that the Collins text, though not producing one of Swift's most energetic and imaginative parodies, nevertheless posed radical questions about the nature of textual authority which deeply perplexed Swift. Specifically, Collins seems to sabotage the notion of priestly authority in matters of biblical exegesis, stressing the individual reader's right to generate his own meanings. Having previously attacked such notions in A Tale of a Tub, Swift sensed in Collins's Discourse the full horror of the Bible itself becoming uncanonical and spiritual authority replaced by anarchy. -

Watson-The Rise of Pilo-Semitism

The Rise of Philo-Semitism and Premillenialism during the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries By William C. Watson, Colorado Christian University Let me therefore beg of thee not to trust to the opinion of any man… But search the scriptures thyself… understanding the sacred prophecies and the danger of neglecting them is very great and the obligation to study them is as great may appear by considering the case of the Jews at the coming of Christ. For the rules whereby they were to know their Messiah were the prophecies of the old Testament… It was the ignorance of the Jews in these Prophecies which caused them to reject their Messiah… If it was their duty to search diligently into those Prophecies: why should we not think that the Prophecies which concern the latter times into which we have fallen were in like manner intended for our use that in the midst of Apostasies we might be able to discern the truth and be established in the faith…it is also our duty to search with all diligence into these Prophecies. If God was so angry with the Jews for not searching more diligently into the Prophecies which he had given them to know Christ by: why should we think he will excuse us for not searching into the Prophecies which he had given us to know Antichrist by? … They will call you a Bigot, a Fanatic, a Heretic, and tell thee of the uncertainty of these interpretations [but] greater judgments hang over the Christians for their remises than ever the Jews felt. -

Was Calvin a Calvinist? Or, Did Calvin (Or Anyone Else in the Early Modern Era) Plant the “TULIP”?

Was Calvin a Calvinist? Or, Did Calvin (or Anyone Else in the Early Modern Era) Plant the “TULIP”? Richard A. Muller Abstract: Answering the perennial question, “Was Calvin a Calvinist?,” is a rather complicated matter, given that the question itself is grounded in a series of modern misconceptions concerning the relationship of the Reformation to post-Reformation orthodoxy. The lecture examines issues lurking behind the question and works through some ways of understanding the continuities, discontinuities, and developments that took place in Reformed thought on such topics as the divine decrees, predestination, and so-called limited atonement, with specific attention to the place of Calvin in the Reformed tradition of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. I. Defining the Question: Varied Understandings of “Calvinism” Leaving aside for a moment the famous “TULIP,” the basic question, “Was Calvin a Calvinist?,” taken as it stands, without further qualification, can be answered quite simply: Yes … No … Maybe ... all depending on how one understands the question. The answer must be mixed or indefinite because question itself poses a significant series of problems. There are in fact several different understandings of the terms “Calvinist” and “Calvinism” that determine in part how one answers the question or, indeed, what one intends by asking the question in the first place. “Calvinist” has been used as a descriptor of Calvin’s own position on a particular point, perhaps most typically of Calvin’s doctrine of predestination. It has been used as a term for followers of Calvin — and it has been used as a term for the theology of the Reformed tradition in general. -

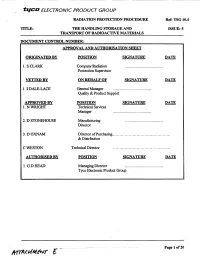

The Handling Storage and Transport

tiicA ELECTRONIC PRODUCT GROUP RADIATION PROTECTION PROCEDURE Ref: TSG 10.4 TITLE: THE HANDLING STORAGE AND ISSUE: 5 TRANSPORT OF RADIOACTIVE MATERIALS DOCUMENT CONTROL NUMBER: APPROVAL AND AUTHORISATION SHEET ORIGINATED BY POSITION SIGNATURE DA.TE 1. S CLARK Company Radiation Protection Supervisor VETTED BY ON BEHALF OF SIGNATURE DA ,TE 1. 1 DALE-LACE General Manager Quality & Product Support APPROVED BY POSITION SIGNATURE DAITE 1. N WRIGHT Technical Services Manager 2. D STONEHOUSE Manufacturing Director 3. D OXNAM Director of Purchasing ............................................ & Distribution C WESTON Technical Director AUTHORISED BY POSION SIGNATURE DA,TE 1. GD HEAD M anaging D irector ........................................ Tyco Electronic Product Group Page 1 of 20 -."+ c. .A .r. tZIca ELECTRONIC PRODUCT GROUP RADIATION PROTECTI(4• PROCEDURE Ref: TSG 10.4 TITLE: THE HANDLING STORAGE AND ISSUE: 5 TRANSPORT OF RADIOACTIVE MATERIALS CONTENTS LIST 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Scope 3.0 Responsibilities 4.0 Definitions 5.0 Procedure 5.1 Equipment & Materials 5.2 Health & Safety 5.2.1 Incident Reporting Procedure 5.3 Procedure 5.3.1 Despatch & Return of Finished Goods & Service Detectors to UK Destinations 5.3.2 Despatch of sample MF/Raft Detectors to UK destinations 5.3.3 Despatch of Finished Goods to International destinations 5.3.4 Packaging & Despatch of Waste (Scrap) or Detectors within UK 5.3.4.1 Removal from Customers Premises (all types) 5.3.4.2 Damaged Detectors (all types) 5.3.4.3 Packaging - Excepted 5.3.4.4 Packaging - I White, -

The Golden Ratio for Social Marketing

30/ 60/ 10: The Golden Ratio for Social Marketing February 2014 www.rallyverse.com @rallyverse In planning your social media content marketing strategy, what’s the right mix of content? Road Runner Stoneyford Furniture Catsfield P. O & Stores Treanors Solicitors Masterplay Leisure B. G Plating Quality Support Complete Care Services CENTRAL SECURITY Balgay Fee d Blends Bruce G Carrie Bainbridge Methodist Church S L Decorators Gomers Hotel Sue Ellis A Castle Guest House Dales Fitness Centre St. Boniface R. C Primary School Luscious C hinese Take Away Eastern Aids Support Triangle Kristine Glass Kromberg & Schubert Le Club Tricolore A Plus International Express Parcels Miss Vanity Fair Rose Heyworth Club Po lkadotfrog NPA Advertising Cockburn High School The Mosaic Room Broomhill Friery Club Metropolitan Chislehurst Motor Mowers Askrigg V. C School D. C Hunt Engineers Rod Brown E ngineering Hazara Traders Excel Ginger Gardens The Little Oyster Cafe Radio Decoding Centre Conlon Painting & Decorating Connies Coffee Shop Planet Scuba Aps Exterior Cleaning Z Fish Interpretor Czech & Slovak System Minds Morgan & Harding Red Leaf Restaurant Newton & Harrop Build G & T Frozen Foods Council on Tribunals Million Dollar Design A & D Minicoaches M. B Security Alarms & Electrical Iben Fluid Engineering Polly Howell Banco Sabadell Aquarius Water Softeners East Coast Removals Rosica Colin S. G. D Engineering Services Brackley House Aubergine 262 St. Marys College Independent Day School Arrow Vending Services Natural World Products Michael Turner Electrical Himley Cricket Club Pizz a & Kebab Hut Thirsty Work Water Coolers Concord Electrical & Plumbing Drs Lafferty T G, MacPhee W & Mcalindan Erskine Roofing Rusch Manufacturing Highland & Borders Pet Suppl ies Kevin Richens Marlynn Construction High Definition Studio A. -

Son Et Lumiere in Bradford York Leads Rail Thinking

SON ET LUMIERE YORK LEADS LEARNING’S STEM SOYUZ LANDS FLAT OUT DAME ZAHA’S IN BRADFORD RAIL THINKING POWERHOUSE IN LONDON FOR GRAPHENE MATHEMATICS RETURN TO CONTENTS PAGE SOYUZ This 360-degree crew’s-eye view of Peake’s Soyuz cabin was shot using a Samsung Gear VR camera by our group’s Digital Lab The Soyuz TMA-19M descent module that While in orbit, Peake had watched a video returned British astronaut Tim Peake safely of the launch party held in December from orbit is the first spacecraft flown by 2015 at the museum and had wished he man to enter the Science Museum Group had been celebrating too with the 3000 HERO PEAKE’S collection. As the UK’s first European schoolchildren who counted down towards Space Agency astronaut, Peake scored his liftoff. When reunited with the Soyuz, he a double scoop when he unveiled the reminisced about first seeing the capsule capsule at the Science Museum in January. crammed with cargo before its launch – On that day – marking the London launch ‘one of the few times I have been grateful SOYUZ LANDS of the 2017 UK–Russia Year of Science and to be only five foot eight’ – and then about Education – the news also broke that he looking on in awe when it sat atop almost would be returning to space. 300 tonnes of rocket fuel before launch. Standing before his Soyuz, which bears Among the dignitaries and media present IN LONDON the scorch marks of its 1600 °C re-entry were Mary Archer, who awarded Peake a from space, he declared how he ‘always Science Museum Fellowship; group trustee gets such enormous pleasure from visits David Willetts, who in 2013, while UK science to the Science Museum’. -

1 September 2017

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (NORTH EAST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2282 PUBLICATION DATE: 01/09/2017 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 22/09/2017 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 08/09/2017 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications and requests reflect information provided by applicants. The Traffic Commissioner cannot be held responsible for applications that contain incorrect information. Our website includes details of all applications listed in this booklet. The website address is: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners Copies of Notices and Proceedings can be inspected free of charge at the Office of the Traffic Commissioner in Leeds. -

Urban Microclimate Limited 16 Torrington Gardens, Perivale, Middlesex UB6 7EN Tel 0799 097 2510 Registered in England and Wales No

rban Umicroclimate Dr Graeme A Flynn Selected Project Experience PhD, M.Eng Axion House Director Led wind microclimate desk study to support the Profile planning application, and develop the landscaping Graeme is the founder of Urban Microclimate Ltd. He strategy to alleviate potential wind effects, for this specialises in design consultation and environmental residential-led development in London. impact assessment for wind effects and natural Battersea Park Road lighting. This includes pedestrian level wind Led wind microclimate studies to support the detailed microclimate, wind loading, snow drift, natural planning application for this residential development ventilation, and daylight and sunlight amenity. in London. Also provided specialist advice during the design development stages, resulting in minimal Graeme has more than 20 years experience in mitigation requirements. aerodynamics and wind engineering, spanning the construction and aerospace industries. Prior to Cherry Park founding Urban Microclimate he was Director of Led wind microclimate studies and daylight / sunlight Microclimate at a large multi-disciplinary consultancy. modelling studies forming part of the EIA to support Prior to this he spent over 10 years with a leading the revised outline application for this dense international wind consultancy, heading the residential development in east London. Subsequently company’s wind microclimate and stadia group and provided specialist consultation during the detailed latterly taking over responsibility for daylight and design phase to optimise the natural lighting and sunlight services. This work included wind tunnel minimise wind mitigation requirements, culminating in testing, numerical modelling and desk-top studies on specialist reports to support the reserved matters stadia, tall buildings, building complexes and application. -

Leeds an INSIDER GUIDE to INVESTING in the CITY

Cover 30/8/13 14:18 Page 1**erica **Macintosh HD:private:var:tmp:folders.504:TemporaryItems: Location Leeds AN INSIDER GUIDE TO INVESTING IN THE CITY Sponsored by Introduction Mojo rising Having attracted investments totalling £6bn while all others hid from the economic storm, “something special” is happening in Leeds… LEEDS LANDMARKS SPRING 2013 – TRINITY LEEDS OPENS Costing £350m, the 1 million sq ft shopping centre has transformed Leeds’ retail fortunes. SUMMER 2013 – FIRST DIRECT ARENA OPENS The £60m performance venue seats 13,500 people and is expected to attract more than one million visitors a year. AUTUMN 2013 The Rugby League World Cup hits our shores and Leeds is one of the host cities. Leeds has been showered in plaudits city that has a new shopping centre, ABOVE in recent years and recognised as music venue, speculative office TRINITY LAUNCH SUMMER 2014 one of Europe’s leading business space and a major sporting event – Leeds is hosting the Grand Depart destinations. And if you’re looking the Grand Depart of the Tour de of the Tour de France, generating for solid proof of the city’s potential, France,” he says. “That’s something an estimated £100m for the local other business leaders have very special.” economy. already committed £6bn to invest- With investments in ultra-fast ment projects. broadband and data centres, the 2014 – WORK STARTS ON The biggest vote of confidence in airport and a new mass urban transit VICTORIA GATE the city came from Land Securities, system – and money being spent on Hammerson will begin work on its which spent £350m building Trinity skills, innovation and collaboration – retail scheme, featuring John Lewis Leeds, a one million sq ft shopping Leeds is continually working to and a super casino.